Полная версия

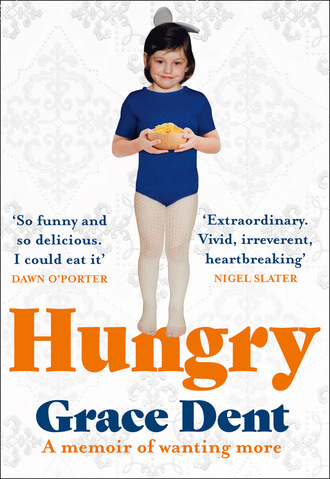

Hungry

I got off semi-lightly, in as much as I was called a slag or an ugly cow by older girls at least every other day. This was just normal and, if anything, I was being provocative. My half-decent posture was definite evidence of supposing I was ‘it’. Reckoning you were ‘it’ in Eighties working-class Britain was a grave crime. It required almost no evidence to prosecute; a confident manner, a new ski jacket, some shoes with a fancy toe cap all constituted putting your head above the parapet in some way.

And in the lunch hall, all our differences were laid bare.

I say differences with a caveat: we were one thousand Caucasian children raised in the Church of England faith. Our backgrounds were as uniformly beige as our lunch plates.

None of us had the sheer brass neck to be openly gay, bi, queer or trans. A ‘tranny’ was something your Uncle Brian might borrow to do a twenty-four-hour booze-buying trip to Calais. None of our parents were especially rich, poor, smothering, feral or absent. Our uniformity only made the bullying more innovative. By my second year at ‘big school’, I had learned – rather depressingly – that when Joanne from the year above sent a message wanting a fight, the pragmatic option was to walk directly over to Joanne by the chips, grab her by the demi-wave and drag her backwards past the millionaire’s shortbread with her skirt riding up so everyone could see her pants. Clever retorts did not work with these people. It is no accident that so few of the working classes go on to choose a life on the debating circuit and choose hobbies like cage fighting instead.

With all this in mind, perhaps it’s unsurprising how the working classes have such a soft spot for that type of school-dinner pudding that they remember making their day feel slightly better – like sweet, cheaply made apple crumble with custard or honking square lumps of chocolate sponge smothered in some sort of pink creamy sauce. I’d dispatch a sainthood to whichever culinary genius invented Australian Crunch, crushed cornflakes, desiccated coconut, cheap margarine, sugar and cocoa-flavoured powder churned into a traybake and topped with thick melted cooking chocolate.

School dinners were where an entire generation of working-class kids learned that beige food is a blanket of happiness to snuggle around you on an otherwise shitty school day. This stays with many of us for life. After a woeful day dealing with dickheads at work, very few people experience a guttural yearning for a bowl of mixed leaves with oil-free dressing.

No.

Give me a chip butty covered in vinegar and so much salt I can feel my heart valves clogging. Give me pizza so inauthentic that it would make a Neapolitan weep. Give me food that helps in the short term but in the long term reduces my lifespan.

When Jamie Oliver finally went to war on school dinners and what mothers fed their kids back in 2005, I couldn’t help thinking: God love him, his heart’s in the right place, but he has no idea what he is taking on. These mothers were my age group, they’d lived my life. Oliver was on a hiding to nothing, telling them a plate of broccoli was a lunch option for their little Lee-Reuben. Even when he managed to ban the Twizzlers, some mams came to the school and pushed emergency Happy Meals through the school fence. It looked shocking, I know, but I understood. They just wanted their kids to be fed and happy.

By the age of fourteen, a division was growing between me and my father.

He could not protect me from Caldew or possibly understand how it felt for me growing up.

He left the heavy lifting of all my hormonal teenage stroppiness to my mother. And as I grew curvier, bolshier, more belligerent and less likely to show my face at school five days in a row, my father hid away from our arguments. I turned my mother’s hair silver with anger. I told every lie I could dream up to stay at home and read Jackie Collins novels in bed. Sore throats, bad heads, heavy periods, imaginary teacher training days. Sometimes just plain old-fashioned screaming ‘I’m not bloody going!’

All this was nobody else’s fault but my own.

Fourteen-year-old girls in the 1980s were a law unto themselves. We did not consider ourselves to be children.

We read Cosmopolitan magazine cover to cover and loved the articles on stronger, harder orgasms. We pooled our pocket money and bought Thunderbird or Merrydown cider or Kestrel lager to drink in the bogs at school discos. We stole Cinzano Bianco from our mothers’ drinks’ cabinets and knocked it back neat with a Feminax period pain pill to get us more dizzily drunk. We danced to ‘Rebel Yell’ by Billy Idol or ‘Blue Monday’ by New Order or ‘Male Stripper’ by Man 2 Man and we had sex in our grandparents’ seaside static caravans or standing up in bus shelters and it was all bloody brilliant. The pubs served us vodka and lime without question and we went to nightclubs without even needing fake ID, just with false birthdays and star signs memorised. We drank snakebite and black or shots of Dubonnet and pints of Caffrey’s and long vodkas made with Rose’s Lime Juice Cordial and Angostura bitters. We doused ourselves in Anaïs Anaïs by Cacherel and had older boyfriends with Sun-In-streaked mullets who drove Ford Fiesta XR2s and Escort Mk 3s, who would get banged up in young offenders’ institutes for low-level soccer hooliganism. We had boyfriends who smoked bongs and listened to AC/DC who were scaffolders and picked us up from school in their Ford Capri to drive us home.

The word grooming was just something posh girls did with their ponies.

We smoked Regal King Size, which we stole from our nans. We wore our school skirts rolled over at the waistline with Pineapple boxer boots and neon fishnet tights and Rimmel Heather Shimmer lipstick and we tried to hide the lovebites on our necks with Constance Carroll concealer stick, although we were secretly proud of them, especially the ones on our boobs. We put ourselves on the pill at the local family planning clinic (carting along random willing teenage boys to play the parts of steady, responsible boyfriends), which the nurses dished out with grateful abandon, because they knew the alternative was that many would fake consent forms to book abortions, which in a time before computerised records was as easy as pie.

And we did all this without many tears.

It didn’t occur to us that we were victims.

We were Generation X, raised without playdates, allergies, safe spaces and CRB checks, when getting your tits felt up – not entirely consensually – at the back of the Manchester Free Trade Hall was, we reckoned, the best part of going to see Spaceman 3. It was a world before TikTok, before cameras in every pocket, before it felt imperative to capture, log and broadcast every experience in order to harvest attention.

Teenagers in the Eighties knew the value of discretion.

Of sworn-to-the-heart secrecy.

Of sneaking about.

And we generally got away with it. And now that Generation X are the parents, we pretend none of it happened at all.

My dad stayed right out of most of this. He buried himself in work and tried hard not to be there at tea time. Thatcherism was working out beautifully for some portions of society – much less so for others – but for him it brought a new way to earn money. With consumerism on the rise, he bought a white Ford Escort van and set himself up as a delivery driver. He acquired a hard-luck-story Alsatian puppy with a black ear whom he called Cilla, who sat in the front seat guarding the goods. People needed more stuff – white goods, home office supplies, even the occasional computer – and now my dad worked night and day to deliver them, never refusing a job.

Dad was happiest when he and Cilla were on the motorway driving away from the fights in our living room. Driving away from the television that never played what he wanted anymore but was now showing ‘that clown’ Morrissey spinning with a handful of gladioli, Michael Hutchence in bike shorts ‘acting like a poof’ or endless episodes of Airwolf while me and David gave each other dead arms.

He found family life – being the one supposedly in charge – no fun at all. My mother took up the slack.

That said, he had very limited experience of being a good example. And his sins had only just come back to haunt him.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.