Полная версия

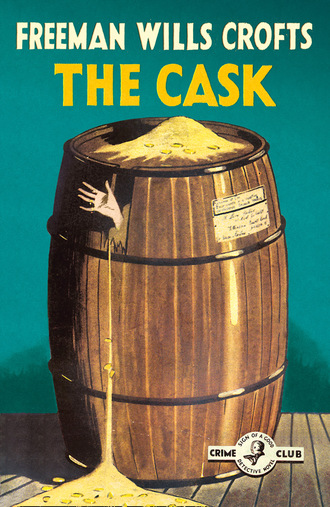

The Cask

Captain M’Nabb was a big, rawboned Ulsterman, with a hooked nose and sandy hair. He was engaged in writing up some notes in his cabin.

‘Come in, sir, come in,’ he said, as Huston made the Inspector known. ‘What can I do for you?’

Burnley explained his business. He had only a couple of questions to ask.

‘How is the trans-shipment done from the railway to your boat at Rouen?’

‘The wagons come down on the wharf right alongside. The Rouen stevedores load them, either with the harbour travelling crane or our own winches.’

‘Would it be at all possible for a barrel to be tampered with after it was once aboard?’

‘How do you mean tampered with? A barrel of wine might be tapped, but that’s all could be done.’

‘Could a barrel be changed, or completely emptied and filled with something else?’

‘It could not. The thing’s altogether impossible.’

‘I’m much obliged to you, captain. Good-day.’

Inspector Burnley was nothing if not thorough. He questioned in turn the winch drivers, the engineers, even the cook, and before six o’clock had interviewed every man that had sailed on the Bullfinch from Rouen. The results were unfortunately entirely negative. No information about the cask was forthcoming. No question had been raised about it. Nothing had happened to call attention to it, or that was in any way out of the common.

Puzzled but not disheartened, Inspector Burnley drove back to Scotland Yard, his mind full of the mysterious happenings, and his pocket-book stored with all kinds of facts about the Bullfinch, her cargo, and crew.

Two messages were waiting for him. The first was from Ralston, the plain-clothes man that he had sent from the docks in a northerly direction. It read:

‘Traced parties as far as north end of Leman Street. Trail lost there.’

The second was from a police station in Upper Head Street:

‘Parties seen turning from Great Eastern Street into Curtain Road about 1.20 p.m.’

‘H’m, going north-west, are they?’ mused the Inspector, taking down a large scale map of the district. ‘Let’s see. Here’s Leman Street. That is, say, due north from St Katherine’s Docks, and half a mile or more away. Now, what’s the other one?’—he referred to the wire—‘Curtain Road should be somewhere here. Yes, here it is. Just a continuation of the same line, only more west, say, a mile and a half from the docks. So they’re going straight, are they, and using the main streets. H’m. H’m. Now I wonder where they’re heading to. Let’s see.’

The Inspector pondered. ‘Ah, well,’ he murmured at last, ‘we must wait till tomorrow,’ and, sending instructions recalling his two plain-clothes assistants, he went home.

But his day’s work was not done. Hardly had he finished his meal and lit one of the strong, black cigars he favoured, when he was summoned back to Scotland Yard. There waiting for him was Broughton, and with him the tall, heavy-jawed foreman, Harkness.

The Inspector pulled forward two chairs.

‘Sit down, gentlemen,’ he said, when the clerk had introduced his companion, ‘and let me hear your story.’

‘You’ll be surprised to see me so soon again, Mr Burnley,’ answered Broughton, ‘but, after leaving you, I went back to the office to see if there were any instructions for me, and found our friend here had just turned up. He was asking for the chief, Mr Avery, but he had gone home. Then he told me his adventures, and as I felt sure Mr Avery would have sent him to you, I thought my best plan was to bring him along without delay.’

‘And right you were, Mr Broughton. Now, Mr Harkness, I would be obliged if you would tell me what happened to you.’

The foreman settled himself comfortably in his chair.

‘Well, sir,’ he began, ‘I think you’re listening to the biggest fool between this and St Paul’s. I ’ave been done this afternoon, fairly diddled, an’ not once only, but two separate times. ’Owever, I’d better tell you from the beginning.

‘When Mr Broughton an’ Felix left, I stayed an’ kept an eye on the cask. I got some bits of ’oop iron by way o’ mending it, so that none o’ the boys would wonder why I was ’anging around. I waited the best part of an hour, an’ then Felix came back.

‘“Mr ’Arkness, I believe?” ’e said.

‘“That’s my name, sir,” I answered.

‘“I ’ave a letter for you from Mr Avery. P’raps you would kindly read it now,” ’e said.

‘It was a note from the ’ead office, signed by Mr Avery, an’ it said that ’e ’ad seen Mr Broughton an’ that it was all right about the cask, an’ for me to give it up to Felix at once. It said too that we ’ad to deliver the cask at the address that was on it, an’ for me to go there along with it and Felix, an’ to report if it was safely delivered.

‘“That’s all right, sir,” said I, an’ I called to some o’ the boys, an’ we got the cask swung ashore an’ on to a four-wheeled dray Felix ’ad waiting. ’E ’ad two men with it, a big, strong fellow with red ’air an’ a smaller dark chap that drove. We turned east at the dock gates, an’ then went up Leman Street an’ on into a part o’ the city I didn’t know.

‘When we ’ad gone a mile or more, the red-’aired man said ’e could do with a drink. Felix wanted ’im to carry on at first, but ’e gave in after a bit an’ we stopped in front o’ a bar. The small man’s name was Watty, an’ Felix asked ’im could ’e leave the ’orse, but Watty said “No,” an’ then Felix told ’im to mind it while the rest of us went in, an’ ’e would come out soon an’ look after it, so’s Watty could go in an’ get ’is drink. So Felix an’ I an’ Ginger went in, an’ Felix ordered four bottles o’ beer an’ paid for them. Felix drank ’is off, an’ then ’e told us to wait till ’e would send Watty in for ’is, an’ went out. As soon as ’e ’ad gone Ginger leant over an’ whispered to me, “Say, mate, wot’s ’is game with the blooming cask? I lay you five to one ’e ’as something crooked on.”

‘“Why,” said I, “I don’t know about that.” You see, sir, I ’ad thought the same myself, but then Mr Avery wouldn’t ’ave written wot it was all right if it wasn’t.

‘“Well, see ’ere,” said Ginger, “maybe if you an’ I was to keep our eyes skinned, it might put a few quid in our pockets.”

‘“’Ow’s that?” said I.

‘“’Ow’s it yourself?” said ’e. “If ’e ’as some game on wi’ the cask ’e’ll not be wanting for to let any outsiders in. If you an’ me was to offer for to let them in for ’im, ’e’d maybe think we was worth something.”

‘Well, gentlemen, I thought over that, an’ first I wondered if this chap knew there was a body in the cask, an’ I was going to see if I couldn’t find out without giving myself away. Then I thought maybe ’e was on the same lay, an’ was pumping me. So I thought I would pass it off a while, an’ I said:

‘“Would Watty come in?”

‘Ginger said “No,” that three was too many for a job o’ that kind, an’ we talked on a while. Then I ’appened to look at Watty’s beer standing there, an’ I wondered ’e ’adn’t been in for it.

‘“That beer won’t keep,” I said. “If that blighter wants it ’e’d better come an’ get it.”

‘Ginger sat up when ’e ’eard that.

‘“Wot’s wrong with ’im?” ’e said. “I’ll drop out an’ see.”

‘I don’t know why, gentlemen, but I got a kind o’ notion there was something in the air, an’ I followed ’im out. The dray was gone. We looked up an’ down the street, but there wasn’t a sign of it nor Felix nor Watty.

‘“Blow me, if they ’aven’t given us the slip,” shouted Ginger. “Get a move on. You go that way an’ I’ll go this, an’ one of us is bound to see them at the corner.”

‘I guessed I was on to the game then. These three were wrong ’uns, an’ they were out to get rid o’ the body, an’ they didn’t want me around to see the grave. All that about the drinks was a plant to get me away from the dray, an’ Ginger’s talk was only to keep me quiet till the others got clear. Well, two o’ them ’ad got quit o’ me right enough, but I was blessed if the third would.

‘“No, you don’t, ol’ pal,” I said. “I guess you an’ me’ll stay together.” I took ’is arm an’ ’urried ’im on the way ’e ’ad wanted to go ’imself. But when we got to the corner there wasn’t a sign o’ the dray. They ’ad given us the slip about proper.

‘Ginger cursed an’ raved, an’ wanted to know ’oo was going to pay ’im for ’is day. I tried to get out of ’im ’oo ’e was an’ ’oo ’ad ’ired ’im, but ’e wasn’t giving anything away. I kept close beside ’im, for I knew ’e’d ’ave to go ’ome some time, an’ I thought if I saw where ’e lived it would be easy to find out where ’e worked, an’ so likely get ’old o’ Felix. ’E tried different times to juke away from me, an’ ’e got real mad when ’e found ’e couldn’t.

‘We walked about for more than three hours till it was near five o’clock, an’ then we ’ad some more beer, an’ when we came out o’ the bar we stood at the corner o’ two streets an’ thought wot we’d do next. An’ then suddenly Ginger lurched up against me, an’ I drove fair into an old woman that was passing, an’ nearly knocked ’er over. I caught ’er to keep ’er from falling—I couldn’t do no less—but when I looked round, I’m blessed if Ginger wasn’t gone. I ran down one street first, an’ then down the other, an’ then I went back into the bar, but never a sight of ’im did I get. I cursed myself for every kind of a fool, an’ then I thought I’d better go back an’ tell Mr Avery anyway. So I went to Fenchurch Street, an’ Mr Broughton brought me along ’ere.’

There was silence when the foreman ceased speaking, while Inspector Burnley, in his painstaking way, considered the statement he had heard, as well as that made by Broughton earlier in the day. He reviewed the chain of events in detail, endeavouring to separate out the undoubted facts from what might be only the narrator’s opinions. If the two men were to be believed, and Burnley had no reason for doubting either, the facts about the discovery and removal of the cask were clear, with one exception. There seemed to be no adequate proof that the cask really did contain a corpse.

‘Mr Broughton tells me he thought there was a body in the cask. Do you agree with that, Mr Harkness?’

‘Yes, sir, there’s no doubt of it. We both saw a woman’s hand.’

‘But might it not have been a statue? The cask was labelled “Statuary,” I understand.’

‘No, sir, it wasn’t no statue. Mr Broughton thought that at first, but when ’e looked at it again ’e gave in I was right. It was a body, sure enough.’

Further questions showed that both men were convinced the hand was real, though neither could advance any grounds for their belief other than that he ‘knew from the look of it.’ The Inspector was not satisfied that their opinion was correct, though he thought it probable. He also noted the possibility of the cask containing a hand only or perhaps an arm, and it passed through his mind that such a thing might be packed by a medical student as a somewhat gruesome practical joke. Then he turned to Harkness again.

‘Have you the letter Felix gave you on the Bullfinch?’

‘Yes, sir,’ replied the foreman, handing it over.

It was written in what looked like a junior clerk’s handwriting on a small-sized sheet of business letter paper. It bore the I. and C.’s ordinary printed heading, and read:

‘5th April, 1912.

‘MR HARKNESS,

on s.s. Bullfinch,

St Katherine’s Docks.

‘Re Mr Broughton’s conversation with you about cask for Mr Felix.

‘I have seen Mr Broughton and Mr Felix on this matter, and am satisfied the cask is for Mr Felix and should be delivered immediately.

‘On receipt of this letter please hand it over to Mr Felix without further delay.

‘As the Company is liable for its delivery at the address it bears, please accompany it as the representative of the Company, and report to me of its safe arrival in due course.

‘For the I. and C. S. N. Co., Ltd.,

‘X. AVERY,

‘per X. X.,

‘Managing Director.’

The initials shown ‘X’ were undecipherable and were apparently written by a person in authority, though curiously the word ‘Avery’ in the same hand was quite clear.

‘It’s written on your Company’s paper anyway,’ said the Inspector to Broughton. ‘I suppose that heading is yours and not a fake?’

‘It’s ours right enough,’ returned the clerk, ‘but I’m certain the letter’s a forgery for all that.’

‘I should imagine so, but just how do you know?’

‘For several reasons, sir. Firstly, we do not use that quality of paper for writing our own servants; we have a cheaper form of memorandum for that. Secondly, all our stuff is typewritten; and thirdly, that is not the signature of any of our clerks.’

‘Pretty conclusive. It is evident that the forger did not know either your managing director’s or your clerks’ initials. His knowledge was confined to the name Avery, and from your statement we can conceive Felix having just that amount of information.’

‘But how on earth did he get our paper?’

Burnley smiled.

‘Oh, well, that’s not so difficult. Didn’t your head clerk give it to him?’

‘By Jove! sir, I see it now. He got a sheet of paper and an envelope to write to Mr Avery. He left the envelope and vanished with the sheet.’

‘Of course. It occurred to me when Mr Avery told me of the empty envelope. I guessed what he was going to do, and therefore I hurried to the docks in the hope of being before him. And now about that label on the cask. You might describe it again as fully as you can.’

‘It was a card about six inches long by four high, fastened on by tacks all round the edge. Along the top was Dupierre’s name and advertisement, and in the bottom right-hand corner was a space about three inches by two for the address. There was a thick, black line round this space, and the card had been cut along this line so as to remove the enclosed portion and leave a hole three inches by two. The hole had been filled by pasting a sheet of paper or card behind the label. Felix’s address was therefore written on this paper, and not on the original card.’

‘A curious arrangement. How do you explain it?’

‘I thought perhaps Dupierre’s people had temporarily run out of labels and were making an old one do again.’

Burnley replied absently, as he turned the matter over in his mind. The clerk’s suggestion was of course possible, in fact, if the cask really contained a statue, it was the likely one. On the other hand, if it held a body, he imagined the reason was further to seek. In this case he thought it improbable that the cask had come from Dupierre’s at all and, if not, what had happened? A possible explanation occurred to him. Suppose some unknown person had received a statue from Dupierre’s in the cask and, before returning the latter, had committed a murder. Suppose he wanted to get rid of the body by sending it somewhere in the cask. What would he do with the label? Why, what had been done. He would wish to retain Dupierre’s printed matter in order to facilitate the passage of the cask through the Customs, but he would have to change the written address. The Inspector could think of no better way of doing this than by the alteration that had been made. He turned again to his visitors.

‘Well, gentlemen, I’m greatly obliged to you for your prompt call and information, and if you will give me your addresses, I think that is all we can do tonight.’

Inspector Burnley again made his way home. But it was not his lucky night. About half-past nine he was again sent for from the Yard. Some one wanted to speak to him urgently on the telephone.

CHAPTER III

THE WATCHER ON THE WALL

AT the same time that Inspector Burnley was interviewing Broughton and Harkness in his office, another series of events centring round the cask was in progress in a different part of London.

Police Constable Z 76, John Walker in private life, was a newly-joined member of the force. A young man of ideas and of promise, he took himself and his work seriously. He had ambitions, the chief of which was to become a detective officer, and he dreamed of the day when he would have climbed to the giddy eminence of an Inspector of the Yard. He had read Conan Doyle, Austin Freeman, and other masters of detective fiction, and their tales had stimulated his imagination. His efforts to emulate their heroes added to the interest of life and, if they did not do him very much good, at least did him no harm.

About half-past six that evening, Constable Walker, attired in plain clothes, was strolling slowly along the Holloway Road. He had come off duty shortly before, had had his tea, and was now killing time until he could go to see the second instalment of that thrilling drama, ‘Lured by Love,’ at the Islington Picture House. Though on pleasure bent, as he walked he kept on practising observation and deduction. He had made a habit of noting the appearance of the people he saw and trying to deduce their histories and, if he did not succeed in this so well as Sherlock Holmes, he hoped he would some day.

He looked at the people on the pathway beside him, but none of them seemed a good subject for study. But as his gaze swept over the vehicles in the roadway it fell on one which held his attention.

Coming along the street to meet him was a four-wheeled dray drawn by a light brown horse. On the dray, upended, was a large cask. Two men sat in front. One, a thin-faced, wiry fellow was driving. The other, a rather small-sized man, was leaning as if wearied out against the cask. This man had a black beard.

Constable Walker’s heart beat fast. He had always made it a point to memorise thoroughly the descriptions of wanted men, and only that afternoon he had seen a wire from Headquarters containing the description of just such an equipage. It was wanted, and wanted badly. Had he found it? Constable Walker’s excitement grew as he wondered.

Unostentatiously he turned and strolled in the direction in which the dray was going, while he laboured to recall in its every detail the description he had read. A four-wheeled dray—that was right; a single horse—right also. A heavily made, iron-clamped cask with one stave broken at the end and roughly repaired by nailing. He glanced at the vehicle which had now drawn level with him. Yes, the cask was well and heavily made and iron clamped, but whether it had a broken stave he could not tell. The dray was painted a brilliant blue and had a Tottenham Court Road address. Here Constable Walker had a blow. This dray was a muddy brown colour and bore the name, John Lyons and Son, 127 Maddox Street, Lower Beechwood Road. He suffered a keen disappointment. He had been getting so sure, and yet— It certainly looked very like what was wanted except for the colour.

Constable Walker took another look at the reddish brown paint. Curiously patchy it looked. Some parts were fresh and more or less glossy, others dull and drab. And then his excitement rose again to fever heat. He knew what that meant.

As a boy he had had the run of the small painting establishment in the village in which he had been brought up, and he had learnt a thing or two about paint. He knew that if you want paint to dry very quickly you flat it—you use turpentine or some other flatting instead of oil. Paint so made will dry in an hour, but it will have a dull, flat surface instead of a glossy one. But if you paint over with flat colour a surface recently painted in oil it will not dry so quickly, and when it does it dries in patches, the dry parts being dull, the wetter ones glossy. It was clear to Constable Walker that the dray had been recently painted with flat brown, and that it was only partly dry.

A thought struck him and he looked keenly at the mottled side. Yes, he was not mistaken. He could see dimly under the flat coat, faint traces of white lettering showing out lighter than the old blue ground. And then his heart leaped for he was sure! There was no possible chance of error!

He let the vehicle draw ahead, keeping his eye carefully on it while he thought of his great luck. And then he recollected that there should have been four men with it. There was a tall man with a sandy moustache, prominent cheekbones, and a strong chin; a small, lightly made, foreign looking man with a black beard and two others whose descriptions had not been given. The man with the beard was on the dray, but the tall, red-haired man was not to be seen. Presumably the driver was one of the undescribed men.

It occurred to Constable Walker that perhaps the other two were walking. He therefore let the vehicle draw still farther ahead, and devoted himself to a careful examination of all the male foot-passengers going in the same direction. He crossed and recrossed the road, but nowhere could he see any one answering to the red-haired man’s description.

The quarry led steadily on in a north-westerly direction, Constable Walker following at a considerable distance behind. At the end of the Holloway Road it passed through Highgate, and continued out along the Great North Road. By this time it was growing dusk, and the constable drew slightly closer so as not to miss it if it made a sudden turn.

For nearly four miles the chase continued. It was now nearly eight, and Constable Walker reflected with a transient feeling of regret that ‘Lured by Love’ would then be in full swing. All immediate indications of the city had been left behind. The country was now suburban, the road being lined by detached and semi-detached villas, with an occasional field bearing a ‘Building Ground to Let’ notice. The night was warm and very quiet. There was still light in the west, but an occasional star was appearing eastwards. Soon it would be quite dark.

Suddenly the dray stopped and a man got down and opened the gate of a drive on the right-hand side of the road. The constable melted into the hedge some fifty yards behind and remained motionless. Soon he heard the dray move off again and the hard, rattling noise of the road gave place to the softer, slightly grating sound of gravel. As the constable crept up along the hedge he could see the light of the dray moving towards the right.

A narrow lane branched off in the same direction immediately before reaching the property into which the dray had gone. The drive, in fact, was only some thirty feet beyond the lane and, so far as the constable could see, both lane and drive turned at right angles to the road and ran parallel, one outside and the other inside the property. The constable slipped down the lane, thus leaving the thick boundary hedge between himself and the others.

It was nearly though not quite dark, and the constable could make out the rather low outline of the house, showing black against the sky. The door was in the end gable facing the lane and was open, though the house was entirely in darkness. Behind the house, from the end of the gable and parallel to the lane, ran a wall about eight feet high, evidently the yard wall, in which was a gate. The drive passed the hall door and gable and led up to this gate. The buildings were close to the lane, not more than forty feet from where the constable crouched. Immediately inside the hedge was a row of small trees.

Standing in front of the yard gate was the dray, with one man at the horse’s head. As the constable crept closer he heard sounds of unbarring, and the gate swung open. In silence the man outside led the dray within and the gate swung to.

The spirit of adventure had risen high in Constable Walker, and he felt impelled to get still closer to see what was going on. Opposite the hall door he had noticed a little gate in the hedge, and he retraced his steps to this and with infinite care opened it and passed silently through. Keeping well in the shadow of the hedge and under the trees, he crept down again opposite the yard door and reconnoitred.

Beyond the gate, that is on the side away from the house, the yard wall ran on for some fifty feet, at the end of which a cross hedge ran between it and the one under which he was standing. The constable moved warily along to this cross hedge, which he followed until he stood beside the wall.

In the corner between the hedge and the wall, unobserved till he reached it in the growing darkness, stood a small, openwork, rustic summer-house. As the constable looked at it an idea occurred to him.