Полная версия

Gulls

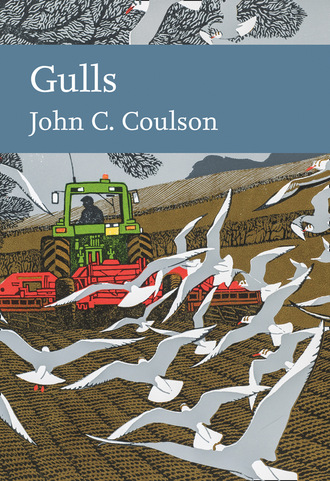

FIG 20. The numbers of nests (pairs) of Black-headed Gulls nesting at Ravenglass in 1939–90.

The history of the Ravenglass colony and other similar sites illustrates two important points. First, egg collecting over many years that was well organised and had an early cut-off had no adverse effects on the colony and did not lead to its desertion. Second, the creation of a nature reserve without effective predator management does not prevent colony desertion; indeed, in recent years there have been other instances of colonies within nature reserves disappearing.

Sunbiggin Tarn colony

The history of the large inland Black-headed Gull colony at Sunbiggin Tarn, near Orton in Cumbria, parallels that of Ravenglass. In 1891, a thousand eggs were said to have been collected from the edge of the colony. The site was estimated to contain 400 pairs in 1938, 1,200 pairs in 1958 and 2,500–3,000 pairs in 1973. The colony continued to grow and reached about 12,500 pairs in 1988 (see below), maintaining similar numbers in 1989, when Foxes were seen. Numbers of gulls then showed a noticeable decline in 1990, and only a few pairs bred in 1991. The colony persisted with a few pairs, and by 2000 had increased to 1,200 pairs, but by 2010 gulls had ceased nesting at the site altogether (Fig. 21).

Direct counting of all nests proved to be impossible at the large Sunbiggin Tarn colony because of the boggy areas within the tarn and the high vegetation, which would be damaged by trampling during a search for nests. A count of the colony was not obtained for the national census in 1985–87, and in 1988 a novel method was used to measure its size. This involved capturing a large sample of the breeding adults in late May and dyeing their tails yellow. A total of 1,010 adults were captured and marked during two weeks by attracting them with food placed about 1–2 km from the colony and then cannon netting them. When marking was completed, the proportion of dyed birds in the colony was obtained by counts of 4,540 adults passing in and out of the site along flight lines. Of these, 186 – or one in 24.4 – had yellow tails, so multiplying the total number dyed by this proportion (24.4) gave a measure of the total number of breeding birds in the colony. This produced an estimate of 24,644 adults (rounded off to 12,500 pairs), identifying it as the largest inland colony in Britain at the time. Unfortunately, Clare Lloyd et al. (1991), in their book reporting the status of seabirds in Britain and Ireland in 1985–88, erroneously recorded this census as 25,000 pairs of Black-headed Gull, not 25,000 individuals.

FIG 21. Part of the large Black-headed Gull colony at Sunbiggin Tarn, Cumbria, during an exceptionally dry spring in 1984. (John Coulson)

Part of the colony at Sunbiggin Tarn could be viewed by people from the nearby road, and they often fed the gulls, which made attracting and capturing the birds in cannon nets much easier. The public’s interest in the well-being and size of this colony was considerable, and not without humour. The investigators netting adult birds had to explain to onlookers what they were doing and that there would be an explosion when the cannons were discharged. On two occasions, the observers remarked that they were puzzled because they could not find a gull in their field guides with a yellow tail, and asked whether this was a rare species! Members of the public often also liked to guess how many gulls were nesting, generally coming up with figures that were widely lower than the actual numbers calculated – most likely because the extent of the colony could not be viewed from a single vantage point. Incidental to the main study, adults with yellow tails were seen feeding in the Lake District and several places on the river Eden up to 40 km from the colony a few days after marking.

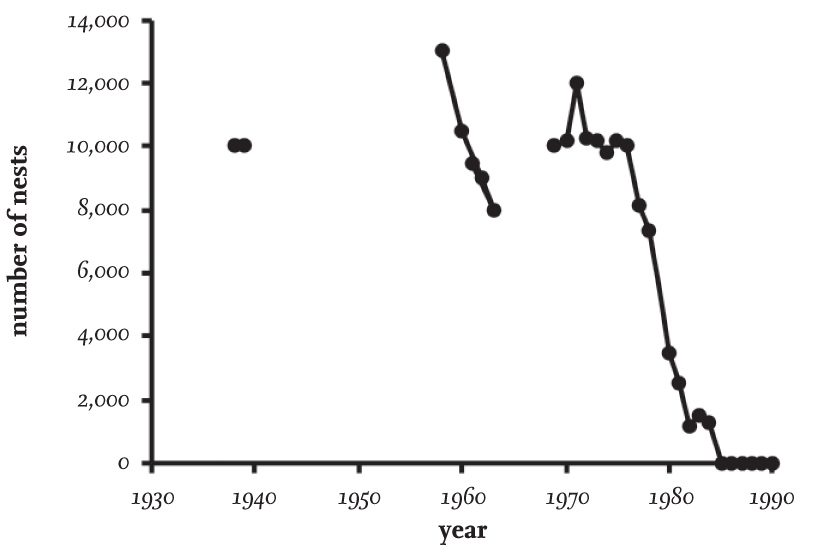

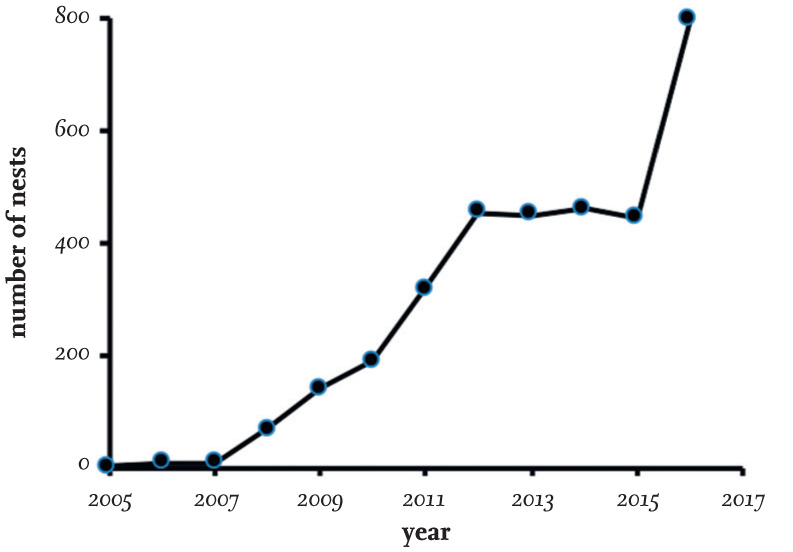

FIG 22. Numbers of Black-headed Gulls nesting on the Sands of Forvie, 1986–2017. Data mainly from the Seabird Colony Register.

Ythan Estuary (Sands of Forvie) colony

Black-headed Gulls have nested at the Sands of Forvie at the mouth of the river Ythan, near Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, for many years. In the late 1980s, about 500 pairs nested there annually, along with Sandwich Terns (Thalasseus sandvicensis), Common Terns (Sterna hirundo) and Eiders (Somateria mollissima). Fox predation became intense in about 1990, when breeding Sandwich Terns and Black-headed Gulls abandoned the area and the number of young Eiders declined. In 1994, steps were taken to reduce and then exclude Foxes from the breeding areas, and in 1998 the first Black-headed Gulls returned to breed. Numbers increased rapidly in the following years and reached more than 1,500 pairs in 2002. This level was not maintained, but numbers exceeded 500 pairs each year up to 2012, when the colony size increased annually until 1,921 pairs were recorded 2016 (Fig. 22).

Foulney and other colonies

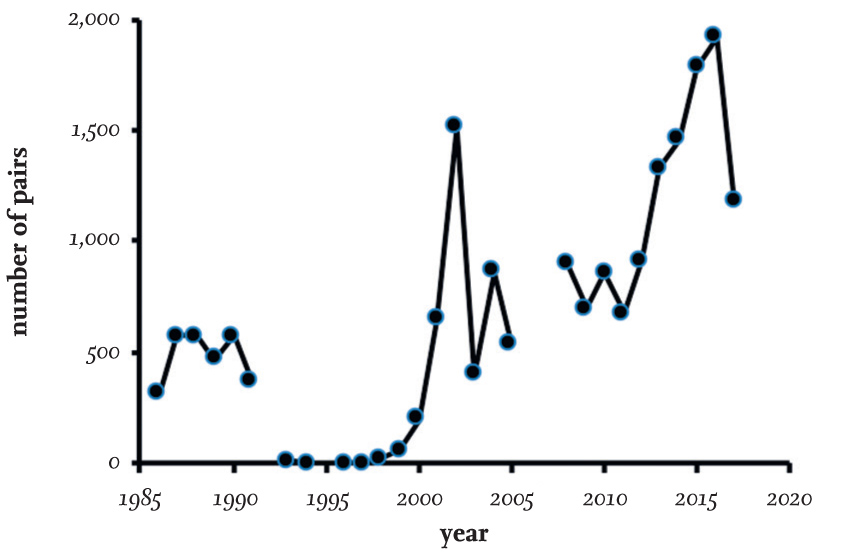

The colony at Foulney in north-west England (Fig. 23) showed a pattern of decline spread over a few years in the late 1980s and early 1990s, before breeding there ceased altogether sometime in or before 1996. As elsewhere, predation of eggs and nestlings was considered the main cause.

FIG 23. The decline and subsequent total desertion of the Black-headed Gull colony at Foulney, a coastal site in Cumbria. Data mainly from the Seabird Colony Register.

FIG 24. The rapid build-up of a Black-headed Gull colony at the RSPB reserve at Saltholme, near Stockton-on-Tees, between 2005 and 2017. Data mainly from the Seabird Colony Register.

There are many other examples of Black-headed Gull colonies that showed appreciably smaller numbers each year before breeding stopped entirely. The national census in 2000 listed 12 large colonies that had disappeared since 1985, plus a further five that had lost more than 89 per cent of the maximum numbers of breeding pairs over recent years. In contrast, nine colonies showed major increases within a short time period, including the colony at Langstone Harbour in Hampshire, which in the 15 years between 1985 and 2000 increased more than 60-fold. Many new colonies had become established and subsequently grew rapidly, such as those at Hamford Water in Essex, Coquet Island in Northumberland, Larne Lough in Northern Ireland, Loch Leven in Scotland, the Ribble Estuary in Lancashire and Saltholme (Fig. 24), a nature reserve near Stockton-on-Tees, County Durham, that has been managed by the RSPB since 2007.

Reasons for colony declines

Egg collecting, particularly if stopped early in the season, has carried on year after year at several Black-headed Gull colonies without resulting in abandonment. And at Ravenglass, Neil Anderson’s investigations (see above) ruled out a possible link between the decline there and contamination associated with the nearby Sellafield nuclear fuel reprocessing and decommissioning plant. In many areas – particularly the fenland of eastern England – colonies have been lost due to drainage and expanding agriculture, which have removed otherwise suitable nesting sites. However, it seems that the main cause of decline and disappearance of Black-headed Gull colonies is predation of eggs, young and sometimes adults. The presence and increase in numbers of mammalian predators, particularly Foxes and American Mink, have been associated with the decline of the colonies at Sunbiggin Tarn, Ravenglass and the Sands of Forvie. During his studies at Ravenglass, Hans Kruuk found that four Foxes killed 230 Black-headed Gulls in one night, and a total of 1,449 adult gulls were killed by Foxes in two consecutive breeding seasons. Studies made at the colony by Ian Patterson during the period of appreciable mammalian predation activity found that scattered and outlying pairs of gulls were entirely unsuccessful, while those in the central core areas, although having a very low success rate, did succeed in rearing a few young (Patterson, 1965).

Once colonies have started to decline, the impact and pressure from the same numbers of Foxes or American Mink produce a vicious spiral that has an increasing impact on the remaining birds. Another predator at Ravenglass was the Hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus), which had developed the habit of consuming the flesh of live gull chicks that had not reached fledging age. Several of the colonies referred to in the past as sites where eggs were collected have now ceased to exist, and some authors have attributed these to uncontrolled egg collecting extending throughout the entire breeding season. It is ironic, therefore, that it was only after egg collecting had stopped at Ravenglass that the colony declined and then disappeared, presumably owing to the lack of efficient predator control.

When a colony disappears in a matter of a few years, it is unlikely that the adults have died, but rather that they have moved to other sites and colonies. The decline at Sunbiggin Tarn following predation resulted in some adults moving to Killington Reservoir alongside the M6 motorway in Lancashire, a move confirmed by a few ringing recoveries of adults previously marked at Sunbiggin Tarn. However, this colony contains nowhere near the numbers of birds recorded breeding at Sunbiggin Tarn, which implies that many adults from Sunbiggin probably moved considerable distances and to several different sites, as no other single large colony was established within 80 km of it at the time of its decline. This is also true of many small, ephemeral colonies on upland moorland in northern England and Scotland. A consequence of this is that mobile groups of Black-headed Gulls are often overlooked, and new colonies can grow rapidly through immigration in only a few years – as has happened at Saltholme (Fig. 24).

Exploitation of eggs and young

In the past, both the eggs and young of Black-headed Gulls were extensively exploited in Britain by humans. Michael Shrubb gives a detailed account of this in his 2013 book, Feasting, Fowling and Feathers, from which I have extracted some of the information given below.

Through the combination of Black-headed Gull numbers, their extensive inland breeding often close to human populations, and the relatively easy access to many nests compared to those of gull species that nest on coastal islands and sea cliffs, the eggs of this species have been exploited more extensively than those of other gulls in Britain and Ireland for the past 500 years and probably longer. In some places in the sixteenth century, nearly fledged young were collected by driving them into nets, and they were then housed and fed until required for human consumption. Some were purchased by the wealthy for 4–5d each, (equivalent to about £7 at today’s prices) or given as gifts, just as we now give flowers. Oxford college records at the time also list Black-headed Gull eggs being bought for a fraction of a penny each.

In the seventeenth century, one landowner is said to have made a profit of £60 in one year (equivalent to about £7,000 today) by collecting and selling gulls’ eggs. Exploitation of young birds probably decreased over time, but they continued to be sent to London markets nonetheless, and egg collecting became more frequent and extensive. Exploitation continued into the eighteenth century, and there are more records at this time of eggs being collected throughout England and Scotland. There are also records of gull colonies disappearing, the causes of which were attributed at the time to excessive egg collecting.

In the nineteenth century, egg collecting for human consumption throughout Britain and Ireland was extensive. In some areas it was organised by the landowners, but elsewhere it appears to have been uncontrolled. Well-established markets existed in London, and eggs collected in bulk in Norfolk and Hampshire were sent there for sale. That the Black-headed Gull was widely distributed as a breeding bird in southern England is evident from records of the large numbers of their eggs being collected and sold in the London markets. For example, in 1800 some 8,000–9,000 eggs were collected at Scoulton Mere in Norfolk, while in 1864 and later, 2,000 eggs a year were collected. From 1858, 700 eggs were taken each year at Hoveton in Norfolk, and in 1864 alone, 2,000 eggs were collected. According to The Spectator (17 April 1897), in 1834 at Stanford in Norfolk, a ‘tumbrel-load’ of eggs was collected in a day and sold for 3d a dozen.

It is probable that landowners enforced a degree of protection to the gull colonies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries owing to the value of the egg trade. In some cases, collecting was limited to taking eggs only from nests that held one or, occasionally, two eggs, to ensure that those collected had not been incubated, and at some but not all sites, collecting ceased on 15 June. As a result, clutches of three eggs were often left untouched, while cessation of collecting in June permitted some gulls to re-lay and breed successfully from late, repeat clutches.

An account of annual egg collecting in Ayrshire, Scotland, in the first 40 years of the twentieth century is given by Ruth Tittensor in a 2012 edition of Ayrshire Notes. The eggs were collected for local bakeries and domestic use, and even for egg fights between youths. Interestingly, the article includes a personal account of egg collecting by a person who later became a senior member of the Nature Conservancy! Elsewhere, the sale of eggs also continued into the twentieth century. In the 1930s, for example, more than 200,000 gull eggs were sold annually at Leadenhall Market in London. Egg collecting increased extensively during the two world wars, with large numbers collected to supplement rationing. An archived Pathé News ciné film shows several Land Girls based at Muncaster Estate during the Second World War collecting baskets of eggs at the large Ravenglass colony and boxing them up in crates ready for dispatch to London. Hugh Cott describes eggs being on sale in Cambridge in 1951 at 9d each. A London market for Black-headed Gull eggs existed for the whole of the twentieth century, with some being sold as ‘plovers’ eggs’.

Today, despite current bird protection Acts, systematic collecting of Black-headed Gulls’ eggs is still permitted in England by licence holders, although there is little general knowledge of the numbers of licences and eggs collected. The licences are issued annually by Natural England for collecting eggs for food consumption. As a result of a request for information, Natural England responded in 2016 by stating that ‘Licences are only issued where evidence of hereditary/ancestral/traditional family rights to collect eggs can be given’. The public body also stated that it seeks ‘to ensure that collection of eggs is sustainable in relation to numbers collected and colony size’. However, I still await a response as to how this is achieved and where the records are deposited, since they do not appear in the Seabird Colony Register or local county bird reports. An accurate census of a colony where many eggs are collected is often difficult to carry out because of the greater spread of laying and repeat clutches.

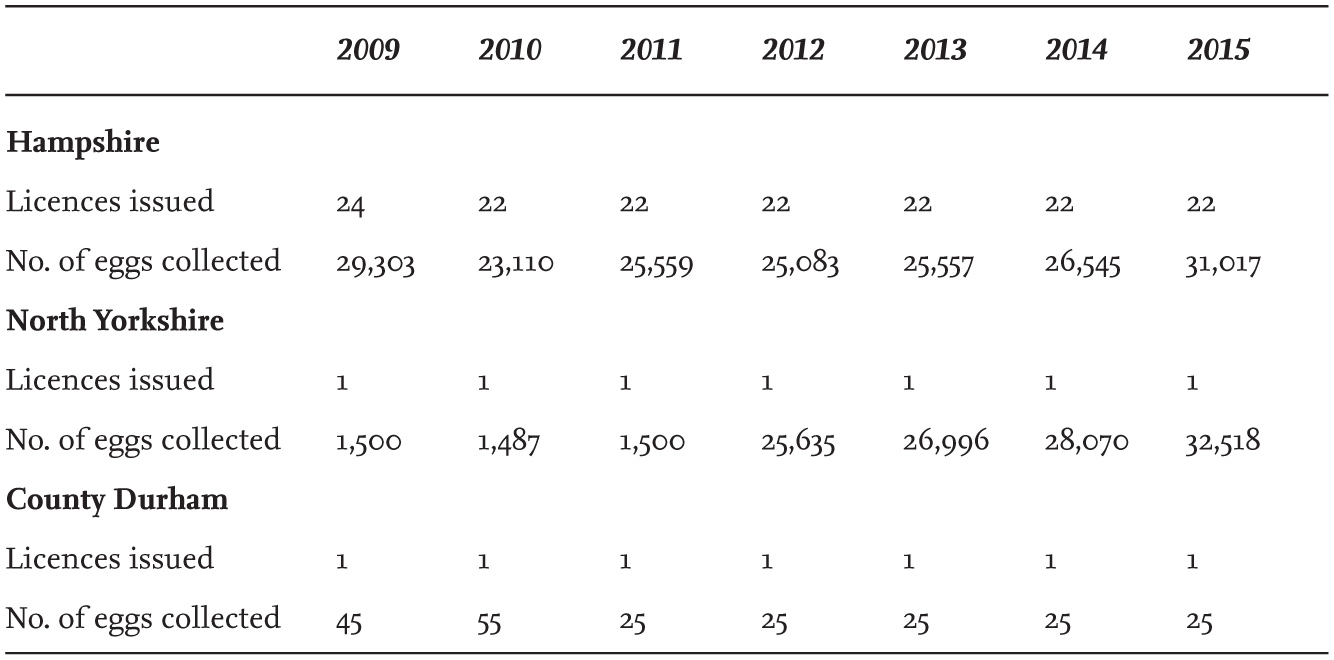

A freedom of information request granted by Natural England in 2016 revealed that it had issued licences recently for egg collection at six sites in England: the North Solent nature reserve in Hampshire; Lymington, Pylewell and Keyhaven marshes, also in Hampshire; Barden Moor in North Yorkshire; and the Upper Teesdale National Nature Reserve in County Durham. Currently, up to 40,000 eggs are collected annually and sent to London. These details are not publicised and I found no information in the published literature. A further freedom of information request to Natural England revealed that in 2015 it issued 24 licences to collect Black-headed Gull eggs in England (22 in Hampshire, one in Yorkshire and one in County Durham). Table 10 shows that the numbers of eggs collected in Hampshire remained at about the same level over the period 2009–15. Those taken in North Yorkshire increased 17-fold between 2011 and 2012, and since then the numbers collected have continued to increase, with more than 32,000 eggs taken in 2015.

No mention of these annual egg collections appear in recent county ornithological reports, while Natural England made the surprising statement that information prior to 2008 ‘has not been retained’. This public body should not destroy historical information on colony sizes and the numbers of eggs collected, and such data should be archived. Natural England also refused to identify the colonies from which eggs were collected, or to whom licences were issued, thereby preventing further research on these activities. How this quango carries out the annual monitoring of the colonies – as it claims to do – remains unknown, and why this information is not deposited in the national Seabird Colony Register, which it supports, requires investigation. It is likely that eggs laid by Mediterranean Gulls (Larus melanocephalus) are being inadvertently taken at some of the colonies for which licences are issued.

TABLE 10. The number of egg-collecting licences issued and Black-headed Gull eggs collected in Hampshire, North Yorkshire and County Durham in 2009–15, as reported by Natural England. The public body stated that data for earlier years have not been retained.

Natural England has indicated that the licences place restrictions on the dates of collecting, these normally covering the period 1 April to 15 May each year. They also restrict the length of time collectors can spend in the colonies on each visit. Natural England revealed that the County Durham licences authorise collection of eggs from three large colonies of gulls, which therefore must be in Upper Teesdale, but the quango is not willing to disclose which colonies are involved.

Black-headed Gull eggs collected in England are currently sold by up-market London stores and find their way onto the menus of several prestigious restaurants. The eggs are normally served hard boiled or lightly boiled and seasoned with celery salt, and a serving containing three eggs may cost anything from £7.50 to £22. One restaurant in 2015 was offering omelettes made from three gulls’ eggs filled with lobster meat.

WINTER ABUNDANCE

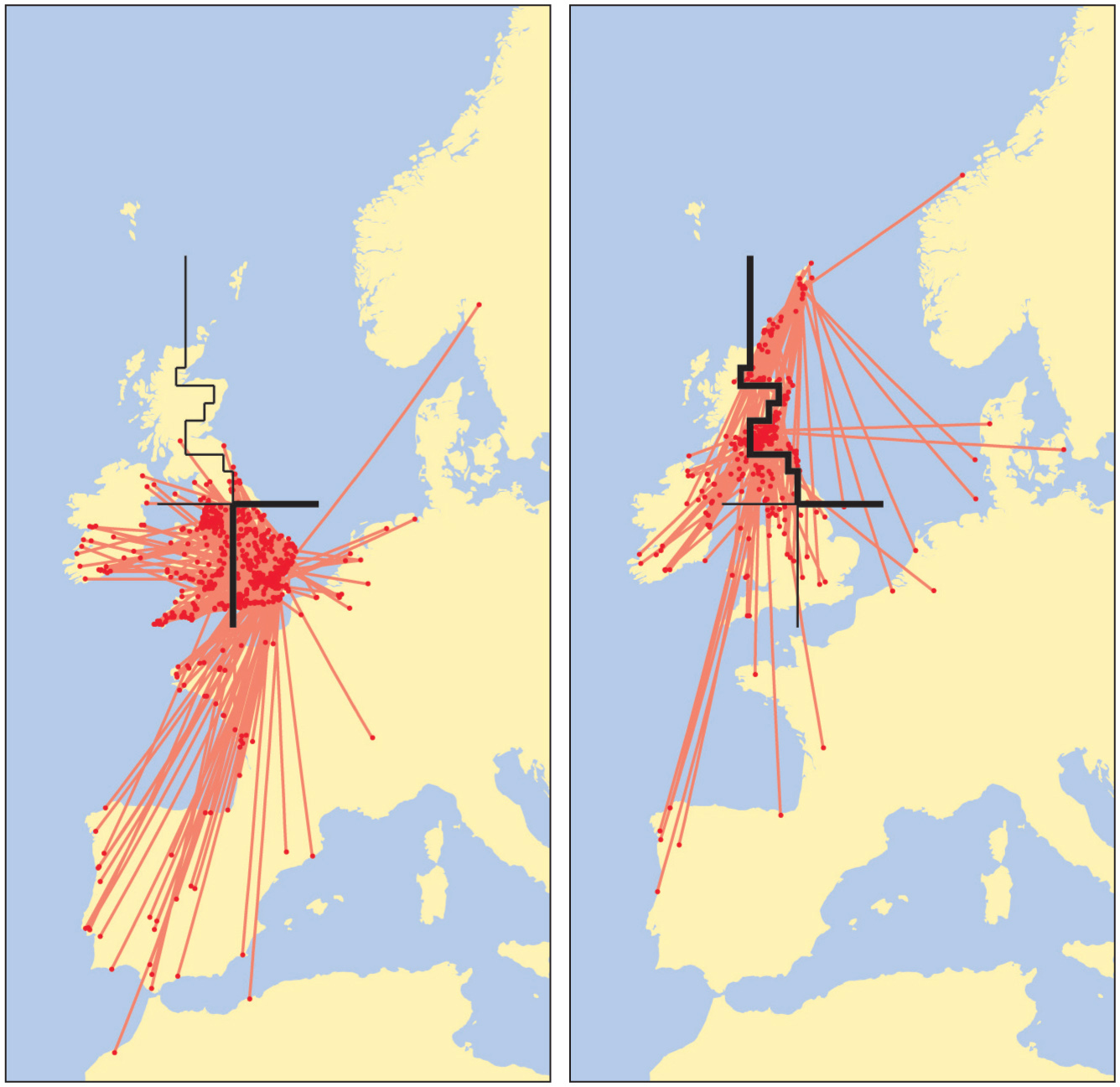

Few British-reared Black-headed Gulls leave the region in winter, with most making only local movements. Of those that do migrate, a higher proportion move to Iberia from south-east England than those reared in north-east Britain (Fig. 25). In contrast, large numbers of Black-headed Gulls move from the Continent to winter in Britain and Ireland.

FIG 25. Movements of Black-headed Gulls ringed as nestlings in south-east England and recovered outside the breeding season, based on 976 recoveries. Right: Similar mapping, but based on 447 recoveries of Black-headed Gulls ringed in north-east Britain. Note that fewer birds moved to Iberia from the north-east and that birds from the two regions have different winter distributions in Ireland. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

The BTO Winter Gull Roost Survey in 2004 estimated that more than 1.6 million Black-headed Gulls were using winter roosts in the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland., and since the total did not include all winter roosts, there are probably more than 2 million individuals wintering here. This number can be compared with 280,000 breeding birds in the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland, which with immatures added comes to about 360,000 individuals. As most of these remain here in winter, it suggests that some 77–82 per cent of wintering Black-headed Gulls recorded in 2004 had moved here from the Continent. Gabriella Mackinnon and I obtained a comparable figure of 71 per cent, derived from ringing recoveries up to 1980 (Fig. 26). Both percentages are rough estimates, but it is clear that a major proportion of the wintering Black-headed Gulls in Britain and Ireland originate from mainland Europe. Without new estimates, it is not known whether these numbers from the Continent have declined in more recent years as a result of the relatively mild winters.

Some readers may find it strange that, despite the satisfactory status and abundance of the Black-headed Gull as a breeding species in Britain, it has been Amber-listed here since 2015 as a species of conservation concern. This is based on the belief that numbers of wintering Black-headed Gulls in Britain have decreased by 33–50 per cent over the last 25 years, based on counts at winter night roosts. Since the British breeding numbers do not appear to have reduced (here), a possible explanation is that a major decline has occurred in northern Europe – the area from which many of the British wintering gulls originate. However, there is little evidence of this apart from Denmark. An alternative explanation for the decline in winter numbers in Britain is that more individuals are remaining on the European mainland during the milder winters encountered in recent years. A preliminary analysis of recent winter ringing recoveries of Black-headed Gulls marked on mainland Europe suggests that the change of wintering areas is more likely to be the explanation. If this is correct and the species is not declining appreciably in Europe as a whole, but is modifying its wintering areas, then is it really a matter of conservation concern? In contrast to the assessment in Britain, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) still regards the Black-headed Gull worldwide as a species of Least Concern.

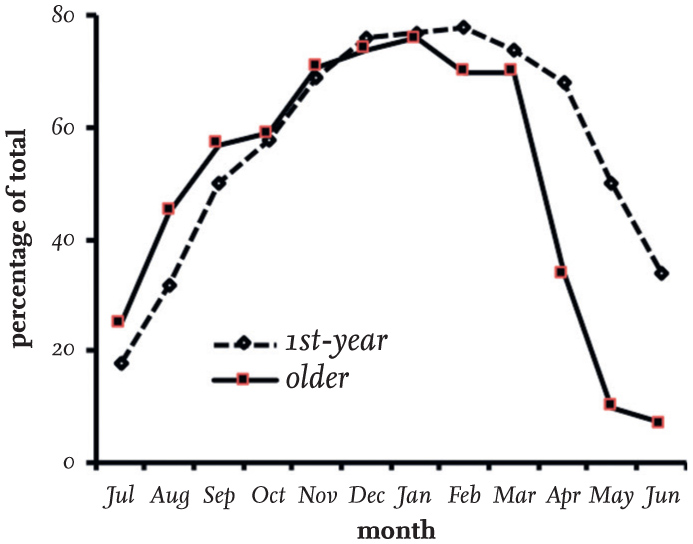

FIG 26. The percentage of Black-headed Gull recoveries reported in Britain and Ireland in each month that were originally ringed in mainland Europe. Note the trend for first-year birds to return to the Continent later. The recoveries of a few Continental birds in May and June may represent rings reported some time after finding.

Arrival of wintering birds

The numbers of Black-headed Gulls arriving in Britain and Ireland for the winter boosts the breeding season population by a factor of about four. These visitors come from a wide range of countries in northern Europe, with most starting their journey at locations around the Baltic Sea (Figs 27 and 28). Their arrival is spread over several months, from late July to early November (see Fig. 26).

The countries of origin of Continental Black-headed Gulls visiting Britain varies slightly with their final destination, with birds flying south-west or west to reach their wintering area (Figs 27 and 28). The exceptions are individuals reared in Iceland, some of which winter in Scotland and Ireland, but most of which avoid England and Wales. Other Black-headed Gulls reared in Iceland have been recovered from the east coast of North America, a route apparently taken by all of those reared in Greenland, although this wintering area is totally avoided by birds breeding in mainland Europe and in Britain.

Fig. 29 shows the number of recoveries of foreign-ringed Black-headed Gulls in Britain and Ireland for each month of the year up to 1985 in relation to those reported monthly from December to February, a period during which it is assumed that all individuals have arrived at their wintering areas. An appreciable proportion of foreign adults, possibly mainly failed breeders, arrive in Britain during July, but only a few young of the year have crossed the North Sea by the end of the month. A small proportion of first-year individuals reared abroad remain in Britain in the following summer, having failed to return to the Continent in the spring. These birds, entering their second year of life and already in Britain in July, are joined by more similar-aged immature birds moving here from the Continent.