Полная версия

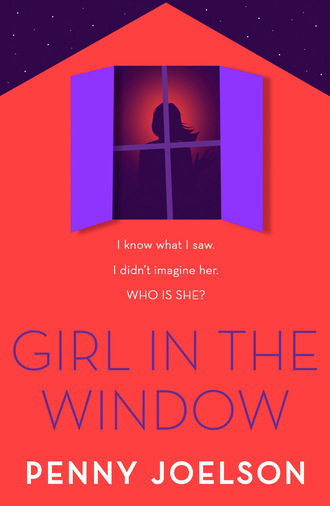

Girl in the Window

‘I don’t get many visitors,’ she says, sighing as she leads me into a rather dark living room. She points to the red velvet armchair. ‘Sit yourself down. Can I get you a tea or coffee? Will you help me eat this cake?’

While she makes the tea, I sit looking around the room. There’s a slight smell of incense and a small statue in the corner that is part elephant, part man. There are photos – some very old sepia ones of people that look like they were taken in India. There’s one black-and-white wedding photo and I wonder if it’s Mrs Gayatri’s own wedding picture. I go closer to look.

Mrs G comes back in with flowery teacups and saucers on a tray. She sets it down on a small, dark, wooden table and then goes back for the cake slices on two matching china plates.

‘I was just looking at your pictures. I hope you don’t mind,’ I say.

‘That was my wedding – so, so many years ago.’ She smiles. ‘My darling husband Vijay. He died ten years ago and I still miss him so much. These are my parents – they of course died many, many years ago – and my five big brothers too.’

‘Do you have no other family – no children of your own?’ I ask.

Mrs G’s mouth turns down, her eyes look suddenly glassy and I wish I hadn’t asked.

‘I’m so sorry – I didn’t mean to upset you,’ I say.

‘It’s fine,’ she assures me. ‘Just hard when everyone I love has gone.’ She sighs again. ‘Life must be hard for you too, being stuck at home so much.’

‘At least I have my mum,’ I say. ‘She’s had to give up her job to look after me, though. And Dad’s working harder than ever.’

‘Are you not going to school at all?’

‘Not since last June,’ I explain. ‘I have a tutor who comes once a week. I have constant pain in my arms and legs and I just get so tired when I do anything. It’s really frustrating. But I think I am improving now.’

‘What is the cause?’ she asks. ‘Do they know why it started?’

I shake my head. ‘I had tonsillitis and I just didn’t get better. No one knows why it happens.’

‘And is there treatment for it?’

‘There’s a bit of research going on, but they know so little about it, there isn’t much on offer. I’m on a waiting list to see a consultant. The doctor just told me to try to pace myself.’

‘But you will recover?’

‘I hope so.’

There’s silence for a moment. I don’t want to think about my illness – about the possibility that I’ll be like this forever. I change the subject.

‘Mrs Gayatri, I wanted to ask you something,’ I say now. ‘I’m interested in the history of our street and I know you’ve lived here a long time. I wondered if you have any memories to share of anything that has happened here?’

‘What kind of thing?’ she asks.

‘Any memorable events, things that shocked you, tragedies?’

‘That’s a strange question!’ Mrs G shakes her head. ‘Surely you are better to focus your energies on happier things. Let me think . . . now there’s Amir and Zainab, of course, across the road. Their daughter died. That was most certainly a tragedy. She was so young. Their only child. That must have been twenty-five years ago. But that’s probably not the sort of thing you mean. Now, what else . . .’

‘The girl across the road – can you tell me any more?’ I ask, leaning forward. ‘What happened to her?’

Mrs G shakes her head. ‘Really, it is upsetting for me even to think about it. Let’s talk of happier things and leave the past behind. It will do your health no good to focus on such sadness. Shall I show you what came in that parcel the other day?’

I nod. I’m frustrated. I am desperate to know more but I don’t want to push her if it’s upsetting her. She walks slowly back into the kitchen and returns with a bird feeder.

‘I love my garden but I’m not up to tending it like I used to,’ she tells me. ‘I like to watch the birds, though. I wondered, as you’re here, whether you might do me a favour and hang it outside for me – on the silver birch. I have the seeds to fill it with. Then I can sit by the back window and watch for the birds. They’ll be grateful now the weather’s getting colder.’

This sounds sad to me – having nothing more interesting to do than watching birds, though maybe it is no sadder than watching the street like I do. I nod again and follow her to the back door, which she unlocks. The garden, which looked overgrown when I last glimpsed it from my parents’ bedroom window, looks far wilder from down here. Neglect has turned it into a jungle.

‘This garden was beautiful once,’ Mrs G says wistfully. ‘My husband and I – we were both keen gardeners. But now I don’t have the strength for it, nor the money to pay a gardener.’

‘I wish I could help,’ I tell her, ‘but I don’t have the strength either.’

Actually, it’s the last thing I’d want to do, even if I did have full strength. Gardening isn’t my idea of fun at all.

‘Of course you don’t, my dear, but it’s a kind thought.’

She seems so sad, I struggle for something positive to say. ‘I guess it’s good for wildlife?’

‘True,’ she says, but I sense this is little consolation.

I fill the feeder and find I can easily hang it on a branch. Mrs G’s house is on the corner and it’s the only one in our row that has a decent sized garden. I’ve never been very interested in gardens, but I do vaguely remember it being much neater in the past. I used to be envious as a young child because we only have a small paved back yard with no lawn or plants at all.

‘Thank you so much!’ she says. ‘That’s wonderful. I’d have to stand on a stool to do that and I knew it wasn’t a good idea.’

‘No, you mustn’t go doing things like that,’ I agree. ‘It’s nice to be able to do something helpful for a change. It’s usually me who needs the help.’

‘Well, I’m very grateful,’ she says.

‘I’d better go now,’ I tell her. I suddenly feel so tired – and she is looking tired, too. She doesn’t protest and I wonder if I have already outstayed my welcome.

‘I hope you will come again,’ she says. ‘It’s been so nice to have some company.’

I’m relieved. I was worried I’d upset her asking about tragedies, and that she wouldn’t want me back. I’m glad I came, though – Mrs G did seem genuinely pleased to see me, and I even learned something about the girl over the road. At least, I may have done. I learned there was a tragedy, and it involved a girl who died. Does that mean the girl I see really is a ghost? I wish I knew the whole story.

7

‘A gummy bear factory! My son is making gummy bears?’

Dad has somehow seen Mum’s latest WhatsApp message from Marek, who has moved from sprinkling cheese on pizzas to making gummy bears. Dad is reeling off a torrent of Polish insults.

‘Why my son? Why me? We bring him here for a good life, he has a good education and he throws it all away to make teddy bear sweets! What did I do to deserve this useless child?’

‘Don’t say that, Dad,’ I protest. Dad has a tendency to be overdramatic, but to me this seems unfair.

‘Sorry, moje kochanie, I don’t want to upset you.’ Dad gently strokes my hair. ‘But gummy bears! Pah! ’

A few days later I get a package from Germany. Marek has written a card saying how much he misses me and enclosed five packets of gummy bears. I wish he’d come home.

I have a bad day for no apparent reason. That’s what it’s like. I spend the morning in bed eating gummy bears and then the afternoon sitting up, looking out of the window. I’ve been looking out every day, but I haven’t seen the girl again.

Mum is worrying that I’m seeing things – as in imagining them. I overheard her telling Dad. I get brain fog sometimes. I can’t think straight and I struggle with the school work my tutor leaves for me, but hallucinations are not a symptom of ME. I know that because I looked it up online. Even so, the more I watch from the window and don’t see the girl, the more I doubt my own memory. I’m wondering if I really saw her at all or if it was a trick of the light. It’s easier to think of her as a ghost than as a real person – but if she was real, perhaps she was staying there and now she’s gone. I hope so, but either way, I can’t stop thinking about her. I wish I could.

It’s almost a relief when my home tutor, Judy, gets here and I can think of something else. She sits on the wicker chair in my room, runs her hand through her thick dark hair and adjusts her big glasses as she checks my attempts at some maths problems. I’m panicking that I’m getting so far behind at school.

‘I want you to give me more work, Judy,’ I tell her. ‘I’m not doing enough. How am I ever going to catch up?’

‘You can only do what you can do,’ she says. ‘I don’t want to give you too much. It will stress you out and that’ll set you back further. But you’re doing OK, and you are getting better. You couldn’t have done maths like this a few weeks ago.’

‘My head is less fuzzy,’ I agree, ‘but, Judy, I’m so far behind! I’m meant to be taking ten GCSEs. Even if I get back to school, how will I do it?

‘Maybe you could cut down on the number of subjects? she suggests.

I shake my head. ‘I don’t want to give any up.’

‘Or you could perhaps stay in Year 9, repeat the year.’

‘Never,’ I say emphatically. ‘Can you imagine how awful that would be? I want to be with my friends.’

‘Don’t think about it now,’ Judy tells me. ‘Keep working like you are and get plenty of rest too. Just focus on one day at a time.’

It’s easy for her to say but the thought of staying down a year, while my friends all do their GCSEs next year and then go into the sixth form without me, is more than I can bear. I won’t let that happen. I have to get better and back to school as soon as possible. If Judy won’t give me more work then I will get it from Ellie.

Once Judy’s gone, I work hard on more maths, but I’m exhausted and I don’t manage as much as I’d hoped. My eyes are drooping. I wish I had more energy and could concentrate better. But Judy has said that I’m improving. So that gives me hope.

The next day, Ellie is due to visit and this time I’m determined to remember to tell her about the girl, as I’m sure she’ll be able to help me think it through. But when she arrives she’s with Lia, and I’m not sure how I feel about it. Lia’s in our form group but I don’t know her that well. We’ve never been friends.

‘You were moaning that no one else comes to see you, so I brought Lia,’ Ellie tells me. ‘We’ve been working together in drama. We’ve done this sketch – you really should see it. It’s hilarious! We might even do it in the show next term!’

She exchanges glances with Lia and they both start giggling. They’re clearly waiting for me to ask them to perform it for me. I feel a tingle of jealousy that they seem so close. I wonder if Lia’s trying to replace me as Ellie’s bestie – but I am also curious about this sketch.

‘You going to show me then?’ I ask.

‘OK – with any luck a laugh will do you good and not tire you out,’ Ellie says, grinning.

The sketch has me in stitches – I laugh so much that I ache. It may hurt physically but I do feel better inside.

‘Do you think you’ll be back at school soon?’ Lia asks, when we can finally speak again.

I shrug. ‘I hope so.’

‘You must be so bored stuck in here,’ she says. ‘Or have you been doing some writing? That story you wrote was so brilliant – it’s fab that you’ve won that competition!’

She sounds genuinely pleased for me and my feelings towards her soften.

‘I don’t really feel up to writing,’ I tell her. ‘I’m sure I will get back to it soon, though.’

‘Lia and I are going to Dimitri’s New Year’s Eve party!’ Ellie says.

‘Dimitri’s? But you can’t stand him!’

‘Oh – he’s all right. Loads of people are going.’

‘Could be fun, I guess.’

‘Yeah, well, I’ll tell you how it goes,’ Ellie says, laughing.

‘Who throws up where and when, you mean?’

Lia giggles.

Ellie turns to me. ‘Remember that time at Erin’s party, Kas?’ She grins. ‘When you had to rescue me?’

‘What happened?’ asks Lia.

It takes a few seconds but the memory comes flooding back. ‘Oh, yeah! You got locked in the loo!’ I laugh.

‘There was someone in the downstairs loo, so I had to go up,’ Ellie tells Lia. ‘Then the door wouldn’t open and I was yelling and yelling – but the music was so loud no one heard me.’

‘And I was dancing with Serene and Erin,’ I say, ‘and waiting for you, and you took ages, so in the end I came up to look for you and heard you shouting!’

‘So how did you get out?’ Lia asks.

‘Erin found a screwdriver and undid the door handle,’ I tell her.

‘I’d have been stuck there for hours otherwise,’ says Ellie. I thought I was going to have to climb out the tiny bathroom window and shimmy down the drainpipe!’

Now it’s me and Ellie laughing together, and Lia’s turn to join in.

After they leave, I feel glad that Lia came. Ellie will always be my best friend, but it was nice to talk to someone else for a change.

I turn my chair back to the window and sit looking out. It’s weird, thinking back to Erin’s party – dancing and laughing with my friends, having fun. It’s like that was another lifetime. But I will get better – I am determined to get back to these things. I see movement in the corner of my eye but when I look there’s nothing. Did the curtain move? Was she there, and did she fade away instantly, as always? I wanted to wave – to let her know I’m here. Perhaps she’d stay visible if she knew someone could see her.

I need to find out more. I don’t want to upset Mrs G, but right now she’s the only one who can help. I need to talk to her again.

I’ve knocked on the door and I’m waiting and waiting for Mrs Gayatri to come and answer it.

She looks surprised. ‘How are you, dear?’ she asks. ‘What can I do for you?’

‘I thought I’d come for a chat, but only if it’s convenient,’ I say.

She smiles and holds the door for me.

‘I’m so glad you came again,’ she says. ‘Those hungry birds have got through all the food already. I’ve seen blue tits there, and great tits. If you could refill the bird feeder for me I’d be so pleased.’

‘Of course,’ I tell her.

‘You do that while I make some tea.’

When I’ve refilled the feeder, we sit on armchairs opposite each other.

‘Mrs Gayatri, you know you told me about the girl who died across the road? I don’t want to upset you, but I’d really like to know more about what happened.’

She frowns. ‘To lose your only child – it’s such a sad thing,’ she says quietly. ‘She was a sweet girl. Meningitis, it was. There’s nothing more to tell really.’

‘Meningitis?’ I repeat. ‘So she was ill?’

I was expecting something more dramatic – something that would give a reason for her to be appearing as a ghost.

Mrs G nods. ‘Nasty illness that – can still be a killer, even now. Her parents moved away in the end. I think it was hard for them to see . . .’ She pauses, her eyes glassy for a moment. ‘To see other children growing up in the street when their child was no longer there. It was empty for over a year after they went, number forty-six. I think people viewing the house could still sense the sadness.’

‘You mean forty-eight?’ I ask.

‘Forty-eight? No.’ Mrs G frowns. ‘What makes you say that? It was forty-six.’

‘Forty-six?’ I stare at her in surprise. ‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes.’ She nods firmly. ‘Poor Shari, she was only five, you know.’

I am speechless, silent, as I try to take this in. This isn’t about my girl at all – it’s the wrong house, and the girl is the wrong age. So now I’m back to knowing nothing at all!

Mrs G looks so sad. I know it was a tragic thing, but I’m surprised that she is this upset.

‘I’m so sorry I asked you about it,’ I tell her. ‘I didn’t mean to upset you.’

‘Never mind,’ she says. ‘Let’s say no more about it.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.