Полная версия

Say Nothing

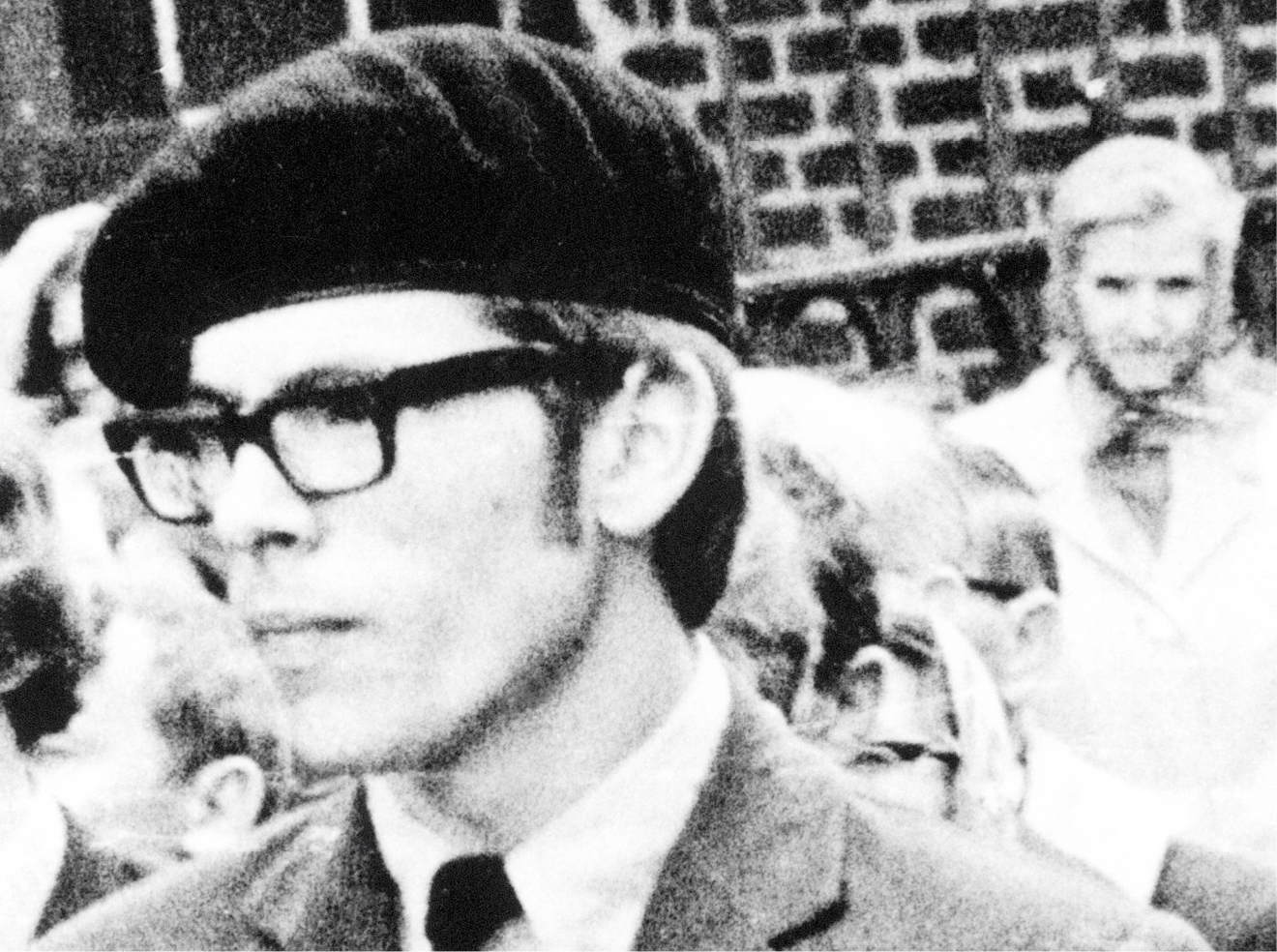

Another person Price became associated with was a tall, angular young man named Gerry Adams. He was an ex-bartender from Ballymurphy who had worked at the Duke of York, a low-ceilinged pub in the city centre that was popular with labour leaders and journalists. Like Price, Adams came from a distinguished republican family: one of his uncles had broken out of Derry jail with her father. Adams had got his start as an activist with a local committee that protested against the construction of Divis Flats. He never attended college, but he was a fearsome debater, smart and analytical, like Dolours. He had joined the IRA a few years before she did, and he was already rising quickly through the Belfast leadership.

Gerry Adams (Kelvin Boyes/Camera Press/Redux)

Price had been loosely acquainted with Adams since childhood. When they were both kids, she used to see him riding with his family on the same buses she did, to republican commemorations at Edentubber or Bodenstown. But now he had reappeared as a firebrand. The first time she recognised him on the back of a lorry, addressing a crowd, she exclaimed, ‘Who does Gerry think he is, standing up there?’ Price found Adams intriguing, and faintly ridiculous. He was a ‘gawky fella with big black-rimmed glasses’, she would recall, and he had a quiet, watchful charisma. Price was irrepressibly outgoing, but she found it difficult to get a conversation started with Adams. He carried himself with an aloof air of authority and referred to her, affectionately, as ‘child’, though he was only a couple of years older than she was. The day after Price sprang James Brown from the hospital, Adams expressed concern about her operational security. ‘It said in the paper that the women were not wearing disguises,’ he murmured, adding reproachfully, ‘I hope that isn’t true.’

Price assured him that the press account was inaccurate, because the sisters had been decked out in blonde wigs, bright lipstick and garish head scarves, ‘like two whores at a hockey match’. Adams took himself pretty seriously, Price thought. But she could laugh at anyone. For security, Adams did not sleep in his own home, and would bed down instead in various billets, some of which were not homes at all, but local businesses. He had taken to sleeping, lately, at a West Belfast undertaker’s. Price found that hilarious. She joked that he slept in a coffin.

‘It was an exciting time,’ she said later. ‘I should be ashamed to admit there was fun in it.’ But there was. She had only just turned twenty-one. Another family might disapprove of what Dolours and Marian were doing, but to Albert and Chrissie Price, there was a sense in which the girls were simply taking up a household tradition, and while you could blame a man for hitting someone, you could not blame him for hitting back. ‘The Provo army was started by the people to set up barricades against the loyalist hordes,’ Albert explained at the time. ‘We beat them with stones at first, and they had guns. Our people had to go and get guns. Wouldn’t they have been right stupid people to stand there? Our people got shotguns at first and then got better weapons. And then the British, who were supposed to protect us, came in and raided our homes. What way could you fight? So you went down and you blew them up. That was the only thing left. If they hadn’t interfered with us, there probably would be no Provo army today.’

When British troops were killed, Albert would freely acknowledge the humanity of each individual soldier. ‘But he is in uniform,’ he would point out. ‘He is the enemy. And the Irish people believe that this is war.’ He was against death, he insisted, but ultimately this was a question of means and ends. ‘If we get a united socialist Ireland,’ Albert Price concluded, ‘then maybe it will all have been worth it.’

As if to underline the futility of nonviolent resistance, when Eamonn McCann and a huge mass of peaceful protesters assembled in Derry one chilly Sunday afternoon in January 1972, British paratroopers opened fire on the crowd, killing thirteen men and wounding fifteen others. The soldiers subsequently claimed that they had come under fire and that they only shot protesters who were carrying weapons. Neither of these assertions turned out to be true. Bloody Sunday, as it would forever be known, was a galvanising event for Irish republicanism. Dolours and Marian were in Dundalk when they heard reports of the massacre. The news filled them with an overpowering anger. In February, protesters set fire to the British embassy in Dublin. In March, London suspended the hated Unionist parliament in Northern Ireland and imposed direct rule from Westminster.

That same month, Dolours Price travelled to Italy to speak in Milan and help to spread the word about oppression of Catholics in Northern Ireland. She lectured about ‘the ghetto system’ and the lack of civil rights. ‘If my political convictions had led me to take part in murder, I would confess without hesitation,’ she told an interviewer, employing the sort of deliberately evasive syntactical construction that would become typical when people described their actions in the Troubles. ‘If I had been commanded to go to kill an enemy of my people I would have obeyed without the slightest fear.’ In a photograph from her appearance there, Price posed like an outlaw, with a scarf pulled across her face.

5

St Jude’s Walk

The McConville family had two dogs, named Provo and Sticky. After Arthur passed away, his oldest son, Robert, might have stepped in to assume responsibility for the family, but in March 1972, when he was seventeen, Robert was interned on suspicion of being a member of the Official IRA – the Stickies. Jean McConville, who had been delicate by temperament to begin with, fell into a heavy depression after her husband’s death. ‘She had sort of given up,’ her daughter Helen later recalled. Jean did not want to get out of bed and seemed to subsist on cigarettes and pills. Doctors in Belfast had taken to prescribing ‘nerve tablets’ – sedatives and tranquillisers – to their patients, many of whom found that they were either catatonically numb or crying uncontrollably, unable to get a handle on their emotions. Tranquilliser use was higher in Northern Ireland than anywhere else in the United Kingdom. In some later era, the condition would probably be described as post-traumatic stress, but one contemporary book called it ‘the Belfast syndrome’, a malady that was said to result from ‘living with constant terror, where the enemy is not easily identifiable and the violence is indiscriminate and arbitrary’. Doctors found, paradoxically, that the people most prone to this type of anxiety were not the active combatants, who were out on the street and had a sense of agency, but the women and children stuck sheltering behind closed doors. At night, through the thin walls of their flat in Divis Flats, the McConville children would hear their mother crying.

Increasingly, Jean became a recluse. Some weeks, she would leave the house only to buy groceries or to visit Robert in prison. It might have simply felt unsafe to venture out. There was a discomfiting sense in Belfast that there was no place where you were truly secure: you would run inside to get away from a gun battle, only to run outside again for fear of a bomb. The army was patrolling Divis, and paramilitaries were dug in throughout the complex. The year 1972 marked the high point for violence during the entirety of the Troubles – the so-called bloodiest year, when nearly five hundred people lost their lives. Jean made several attempts at suicide, according to her children, overdosing on pills on a number of occasions. Eventually, she was admitted to Purdysburn, the local psychiatric hospital.

Nights were especially eerie in Divis. People would turn out all their lights, so the whole vast edifice was swathed in darkness. To the McConville children, one night in particular would forever stand out. Jean had recently returned from the hospital, and there was a protracted gun battle outside the door. Then the shooting stopped and they heard a voice. ‘Help me!’ It was a man’s voice. Not local.

‘Please, God, I don’t want to die.’ It was a soldier. A British soldier. ‘Help me!’ he cried.

As her children watched, Jean McConville rose from the floor, where they had been cowering, and moved to the door. Peeking outside, she saw the soldier. He was wounded, lying in the gallery out in front. The children remember her re-entering the flat and retrieving a pillow, which she brought to the soldier. Then she comforted him, murmuring a prayer and cradling his head, before eventually creeping back into the flat. Archie – who, with Robert in prison, was the oldest child there – admonished his mother for intervening. ‘You’re only asking for trouble,’ he said.

‘That was somebody’s son,’ she replied.

The McConvilles never saw the soldier again, and to this day the children cannot say what became of him. But when they left the flat the next morning, they found fresh graffiti daubed across their door: BRIT LOVER.

This was a poisonous allegation. In the febrile atmosphere of wartime Belfast, for a local woman to be seen consorting with a British soldier could be a dangerous thing. Some women who were suspected of such transgressions were subjected to an antique mode of ritual humiliation: tarring and feathering. A mob would accost such women, forcibly shave their heads, anoint them with warm and sticky black tar, then shower a pillowcaseful of dirty feathers over their heads and chain them by the neck to a lamppost, like a dog, so that the whole community could observe the spectacle of their indignity. ‘Soldier lover!’ the mob would bray. ‘Soldier’s doll!’

In an environment where many married men were being locked up for long stretches, leaving their wives alone, and where cocky young British soldiers were patrolling the neighbourhoods, deep-seated fears of infidelity, both marital and ideological, took hold. Tarring and feathering became an official policy of the Provisional IRA, which the leadership publicly defended as a necessary protocol of social control. When the first few cases turned up at local hospitals, the befuddled medical personnel had to consult with the maintenance crews who took care of their buildings about the best method for removing black tar.

It felt to Michael McConville as if he and his family were strangers in a strange land. Expelled from East Belfast for being too Catholic, they were outsiders in West Belfast for being too Protestant. After their home was marked with the graffiti, what few local friends they had no longer wanted anything to do with them. Everywhere they turned, they found themselves in an adversarial situation. Archie was badly beaten by the youth wing of the Provos and had his arm broken for refusing to join the organisation. Helen and a friend were harassed by a regiment of soldiers. Helen would later suggest that her mother may have further alienated the family from their neighbours by declining to take part in ‘the chain’, the hand-to-hand system for hiding weapons during police searches of the complex; Jean feared that if she was caught with a gun in the house, she might lose another child to prison. At a certain point, the family dogs, Provo and Sticky vanished. Someone had shoved the animals down a rubbish chute, where they died.

Michael had asthma, and Jean worried that the gas heating in the flat was aggravating it. She requested a transfer, and the family was granted a new flat, in another section of Divis Flats called St Jude’s Walk. They packed their belongings and made the short move into the new space. It was slightly larger than the previous one, but otherwise not much different.

Christmas was coming, but the city was hardly festive. Many shops were boarded up and closed, because they had been bombed. Jean McConville’s only indulgence in those days was a regular excursion to play bingo at a local social club. Whenever she won anything, she would give the children twenty pence each. Occasionally, she would bring home enough to buy one of them a new pair of shoes. One night after the family had moved into the new flat, Jean went with a friend to play bingo. But on that particular evening, she did not come home.

Shortly after 2 a.m., there was a knock at the door. It was a British soldier, who informed the McConville kids that their mother was at a barracks nearby. Helen raced to the barracks and found Jean, bedraggled and shoeless, her hair all over the place. Jean said that she had been at the bingo hall when someone came in and told her that one of the children had been hit by a car, and that someone was waiting outside to take her to the hospital. Alarmed, she left the bingo hall and got into the car. But it was a trap: when the door opened, Jean was pushed onto the floor and a hood was placed over her head. She was taken to a derelict building, she said, where she was tied to a chair, beaten and interrogated. After she was released, some army officers found her wandering the streets, distressed, and brought her to the barracks.

Jean couldn’t – or wouldn’t – say who it was that had abducted her. When Helen wondered what kinds of questions they had been asking, Jean was dismissive. ‘A load of nonsense,’ she said. ‘Stuff I knew nothing about.’ Jean could not sleep that night. Instead she sat up, her face bruised, her eyes black and blue, and lit one cigarette after another. She told Helen that she missed Arthur.

The children would later recall that it was the following evening that Jean sent Helen out to fetch fish and chips for dinner. She filled a bath, to try to soothe the pain of the beating she had taken the night before. As Helen was leaving, she said, ‘Don’t be stopping for a sneaky smoke.’

Helen made her way through the labyrinthine passages of Divis to a local takeaway where she ordered dinner and waited for it. When the food was ready, she paid, took the greasy bag, and started to walk back. As she entered the complex, she noticed something strange. People were loitering on the balconies outside their flats. This was the sort of thing that local residents did in the summertime. There were so few places for recreation in Divis that kids would play ball on the balconies and parents would hang about on temperate evenings, leaning in the doorways, gossiping over cigarettes. But not in December. As Helen got closer to the new flat and saw the people gathered outside, she broke into a run.

6

The Dirty Dozen

A vacant house stood on Leeson Street, opposite the short block known as Varna Gap. Such derelict properties pockmarked Belfast’s landscape – burned out, gutted or abandoned, their windows and doors covered in plywood. The people who lived there had simply fled and never come back. Across the street from the vacant house, Brendan Hughes stood with a few of his associates from D Company. It was a Saturday, 2 September 1972.

Looking up, Hughes noticed a green van appear some distance away and begin to approach, along Leeson Street. He watched the van closely, something about it making him uneasy. He usually carried a handgun, but that morning an associate had borrowed it so that he could use it to steal a car. So Hughes found himself unarmed. The van drove right past him, close enough for Hughes to briefly glimpse the driver. It was a man. Not one he recognised. He looked nervous. But the van kept moving, right on down through McDonnell Street and onto the Grosvenor Road. Hughes watched it disappear. Then, just to be on the safe side, he sent one of his runners to fetch a weapon.

At twenty-four, Hughes was small but strong and nimble, with thick black eyebrows and a mop of unruly black hair. He was the officer commanding – ‘the OC’ – for D Company of the Provisional IRA, in charge of this part of West Belfast, which made him a target not just for loyalist paramilitaries, the police and the British Army but for the Stickies (the Official IRA) as well. Eighteen months earlier, Hughes’s cousin Charlie, his predecessor as OC of D Company, had been shot and killed by the Officials. So Hughes was ‘on the run’, in the parlance of the IRA: he was living underground, a man targeted by multiple armed organisations. In rural areas, you could stay on the run for years at a time, but in Belfast, where everybody knew everybody, you would be lucky to stick it out for six months. Someone would get you eventually.

Hughes had joined the Provos in early 1970. It was through his cousin Charlie that he had initially got involved, but he soon established himself in his own right as a shrewd and tenacious soldier. Hughes moved from house to house, seldom sleeping in the same bed on consecutive nights. D Company’s territory embraced the Grosvenor Road, the old Pound Loney area, the Falls Road – the hottest territory in the conflict. Initially, the company had only twelve members, and they became known as the Dogs, or the Dirty Dozen. Hughes adhered to a philosophy, instilled in him at a young age by his father, that if you want to get people to do something for you, you do it with them. So he wasn’t just sending men on operations – he went along on the missions himself. Dolours Price first met Hughes when she joined the IRA, and she was dazzled by him. ‘He seemed to be a hundred places at the one time,’ she recalled, adding, ‘I don’t think he slept.’ Despite his small stature, Hughes struck Price as a ‘giant of a man’. It meant something to her, and to others, that he asked no volunteer to do anything he would not do himself.

D Company was carrying out a dizzying number of operations, often as many as four or five each day. You would rob a bank in the morning, do a ‘float’ in the afternoon – prowling the streets in a car, casting around, like urban hunters, for a British soldier to shoot – stick a bomb in a booby trap before supper, then take part in a gun battle or two that night. They were heady, breakneck days, and Hughes lived from operation to operation – robbing banks, robbing post offices, holding up trains, planting bombs, shooting at soldiers. To Hughes, it seemed like a grand adventure. He thought of going out and getting into gunfights the way other people thought about getting up and going to the office. He liked the fact that there was a momentum to the operations, a relentless tempo, which fuelled and perpetuated the armed struggle, because each successful operation drew new followers to the cause. In the words of one of Hughes’s contemporaries in the IRA, ‘Good operations are the best recruiting sergeant.’

As the legend of Brendan Hughes, the young guerrilla commander, took hold around Belfast, the British became determined to capture him. But there was a problem: they did not know what he looked like. Hughes’s father had destroyed every family photograph in which he appeared, knowing that they could be used to identify him. The soldiers referred to him as ‘Darkie’, or ‘the Dark’, on account of his complexion, and the name stuck, a battlefield sobriquet. But the British did not know what his face looked like, and on many an occasion, Hughes had walked right past the soldiers’ sandbagged posts, just another shaggy-haired Belfast lad. They didn’t give him a second look.

The soldiers would go to his father’s house and rouse him from bed, looking for Hughes. Once, when they hauled his father in for questioning, Hughes was incensed to learn that after two days of interrogation, the old man had been forced to walk home barefoot. The soldiers told his father that they weren’t looking for Brendan in order to arrest him; their intention was to kill him.

This was not an idle threat. The previous April, an Official IRA leader named ‘Big Joe’ McCann had been walking, unarmed, one day when he was stopped by British troops. He tried to flee but was shot. McCann had dyed his hair as a disguise, but they recognised him. He was only wounded by the initial shots, and he staggered away. But rather than call an ambulance, the soldiers fired another volley to finish the job. When they searched his pockets, they found nothing that could plausibly be described as a weapon, just a few stray coins and a comb for his hair.

The runner had not yet returned with a gun for Hughes when the van reappeared. Five minutes had passed, yet here it was once more. Same van. Same driver. Hughes tensed, but again the van drove right past him. It continued on for twenty yards or so. Then the brake lights flared. As Hughes watched, the back doors swung open, and several men burst out. They looked like civilians – tracksuits, trainers. But one had a .45 in each hand, and two others had rifles; as Hughes turned to run, all three of them opened fire. Bullets swished past him, slamming into the façades of the forlorn houses as Hughes tore off and the men gave chase. He sprinted onto Cyprus Street, the men pounding the pavement behind him, still firing. But now Hughes began to zigzag, like a gecko, into the warren of tiny streets.

He knew these streets, the hidden alleys, the fences he could scale. He knew each vacant house and washing line. There was a quote attributed to Mao that Hughes was partial to, about how the guerrilla warrior must swim among the people as a fish swims through the sea. West Belfast was his sea: there was an informal system in place whereby local civilians would assist young paramilitaries like Hughes, allowing their homes to be used as short cuts or hiding places. As Hughes was scrambling over a fence, a back door would suddenly pop open long enough for him to dart inside, then just as quickly close behind him. Some of the residents were intimidated by the Provos and felt they had little choice but to cooperate, while others assisted out of an unforced sense of solidarity. When property was damaged in one of Hughes’s operations, he would pay compensation to the family. He cultivated the community, knowing that without the sea, the fish cannot survive. There was a local invalid who lived on Cyprus Street, ‘Squire’ Maguire, and at the height of the madness, with fires and police raids and riots in the street, residents in the area would occasionally see Brendan Hughes carrying Maguire on his back a few doors down to the pub so that Maguire could have a pint, then dutifully returning to bring him home a short while later. Once, a British soldier in the Lower Falls area caught Hughes in the sights of his rifle. Finger on the trigger, he was ready to open fire when an elderly woman stepped out of some unseen doorway and planted herself in the path of his weapon, then informed him that he would not be shooting anybody on her street on that particular evening. When the soldier looked up, Hughes was gone.

With his pursuers still clomping after him, firing wildly, Hughes veered onto Sultan Street. He had a specific destination in mind: a call house on Sultan Street. Call houses were usually regular homes, occupied by ordinary families, that happened to double as clandestine Provo facilities. Behind one particular door, on a street of identical brick houses with identical wooden doors, would be a secret refuge that could function as a safe house, a waiting room, or a dead drop. The families that lived in these homes deflected any suspicion from authorities. You might show up after midnight, haggard from a gruelling day on the run, and they would lift slumbering children out of their beds, affording you a precious night of rest.

At the corner of Sultan Street, a baker’s van was delivering bread, and as Hughes ran by it, the men behind him let off a volley of bullets, which punctured the van and shattered its windows. He kept pushing, sprinting the length of Sultan, desperate to reach the house before one of those bullets caught him. In addition to its other uses, a call house sometimes functioned as an arms depot. Hughes had become known to the British Army for his willingness to flit around the streets of the Falls area and engage their high-calibre weapons with his little World War II-era .45. The troops had developed what one later described as a ‘grudging admiration for this little bugger who had taken on an elite military unit with a handgun’. But Hughes recognised at a certain point that he needed heavier weapons if he was going to compete. One day, a sailor of his acquaintance came back from a voyage to America with a catalogue for the Armalite rifle – a lightweight, accurate, powerful semi-automatic that was easy to clean, easy to use, and easy to conceal. Hughes fell in love with the weapon. He convinced the Provos to import the Armalite, employing an audacious scheme. Cunard Lines had recently launched the Queen Elizabeth II, a luxury cruise liner that would crisscross the Atlantic, transporting well-heeled passengers between Southampton and New York. A thousand crew members worked on the ship, many of them Irish. Some of them also happened to work for Brendan Hughes. In this manner, Hughes used a ship named after the British queen to smuggle weapons to the IRA. When the guns arrived, fresh graffiti on the walls of West Belfast heralded a game change: GOD MADE THE CATHOLICS, BUT THE ARMALITE MADE THEM EQUAL.