полная версия

полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

My father was the most explosive and intolerant adult in our building. That meant that the players enjoyed every opportunity to drive him crazy and listen to his yelling.

Perhaps that was the reason why most of the time a ball tossed into the air wouldn’t hit the asphalt, the door of the building or Dora’s veranda but rather our window.

That was the reason I would watch the game from the veranda with a feeling of dread and not join them outside.

Our window had already been broken several times. I didn’t enjoy seeing Father fly into a rage, so I tried to stay away from the players.

When the ball smashed into our window, I had just enough time to jump aside so the broken glass wouldn’t fall on me.

Before the clinking and clanking could die out, I heard the stomping of feet – the frightened boys rushed away in all directions. It was safer to listen to Yuabov’s raging from a distance. I looked around. There was the black rubber ball I knew so well among the fragments of glass on the floor of the veranda. This time, the ball looked somewhat smug. It would be fun to draw eyes and a nose on it with chalk, and a mouth would appear all by itself, smiling broadly, as if to say, “There are no obstacles I cannot overcome.”

I held the ball in my hands, then laid it in the corner. There was no one to return it to since the boys were hiding. And, as I later understood, I didn’t want to do them such a favor – after all, they had broken our window.

All right, it can stay here for now, I decided. Let them come over to get it themselves. As a victim, I sort of sided with my father. I took malicious pleasure in the thought of the inevitable punishment the boys would be subjected to and didn’t think about the possible consequences of my choice.

In the evening, there was a knock at our door. Vasily Nikolayevich, Kolya and Sasha’s father, entered. In our part of the building he was considered an important person – Vasily worked in retail, and he would help some people obtain foodstuffs that were in short supply, like meat, for example.

That didn’t apply to our family. Hardly anyone ever wanted to help my father.

Vasily remained in the hallway, exchanged a few words with Mama and asked her whether Amnun was home. Father walked into the hallway, and they exchanged greetings.

“Please give me the children’s ball,” the neighbor requested.

“Yes, I have it,” Father said slowly. “But first let’s have new windowpane installed.”

At this point, Kolya’s father looked at me as I stood quietly at the door to my room.

“My kids stay in their room when the adults talk,” he informed me.

I had no choice, so I went into my room and closed the door. It goes without saying that I pressed my ear against it.

At first, the voices sounded quite calm.

“It’s our ball, it’s Kolya’s… My kids didn’t break your window. They say Server from the next entrance did it,” Vasily said in his deep voice.

“I don’t care whether it was Server or not … They were playing together, right? So, they are all responsible. I’ll return the ball after the glass is replaced,” Father answered in a monotone.

“Listen, Amnun…” Vasily said with irritation. “I’ve already explained that Kolya had nothing to do with it.”

Explaining anything to Father was a lost cause. He was stubborn and never made concessions for the sake of maintaining good relations with people, even when it was an issue regarding children. He just didn’t know the meaning of concession, magnanimity, or negotiations.

Father was an athlete and a coach, and he most likely viewed any conflict as a contest where he was facing an opponent. And an opponent had to be defeated. No compromises!

“I’m not going to give it back. Get it?”

“Don’t you understand…”

The voices were getting louder. Shouts and stomping of feet were heard. I craned my neck and stuck my head out into the hallway. The fathers were grappling at the door. Mama ran out of the kitchen shouting, “Papesh, stop it! Vasily Nikolayevich, how can you?” And, naturally, she got it too. Infuriated, Father pushed her so hard she almost hit the wall. That was probably what brought Vasily to his senses. He mumbled, “What a nut! Ester, I’m sorry…” and he left, slamming the door behind him.

After that, Kolya and Sasha, whose ball it was, stopped hanging around with me; Edem and Rustem too.

Seated close to the open windows of the veranda, listening enviously to the kharks, without realizing it I began thinking about our relationship.

It wasn’t the first time the boys had quarreled with me. Sometimes they stopped hanging out with me even without quarreling. Quarrels and fights among boys are a normal thing. They might fight or quarrel, and an hour later they’ve forgotten all about it.

But this time it was different; it was something else.

And then I realized – it was because of him just about every time we quarreled, because of my father. Of course… why I hadn’t I realized it before? As soon as he would quarrel with one of the neighbors, one who had kids, my friends would begin to shun me. And he quarreled so often! Perhaps the boys heard their parents discuss it at home, talk about my father… I couldn’t imagine what they might say about him. I always understood that Father’s character was known to everybody in our building, that people were afraid of him and tried to avoid him. I knew better than anyone else how he treated Mama and us kids, and I had also seen many times how he treated other people.

I would call Father’s character unpredictable. He could help a person and he could be generous, but then he would stop talking to that person for some unknown reason, without explaining anything. And he always had to have his own way, never listening to reason, demonstrating utter stubbornness.

Yes, they didn’t like my father in our building. But what did that have to do with me?

Standing on the veranda and listening to the spitting, I bitterly pondered all of that.

I knew that we would make up soon, that the boys would come up to me and begin to talk to me, ask me to play with them. But that didn’t make what I felt now any less bitter. We would make up, but then would they refuse to hang out with me again later? When would it happen? And how many times would I have to put up with insults? Didn’t the boys understand that I myself suffered much more because of my father than any of them did?

Aa-khem, aa-khem could still be heard from the third floor, as if my friends who were standing up there were saying, “And we don’t give a … spit.”

Chapter 21. Sunday Delights

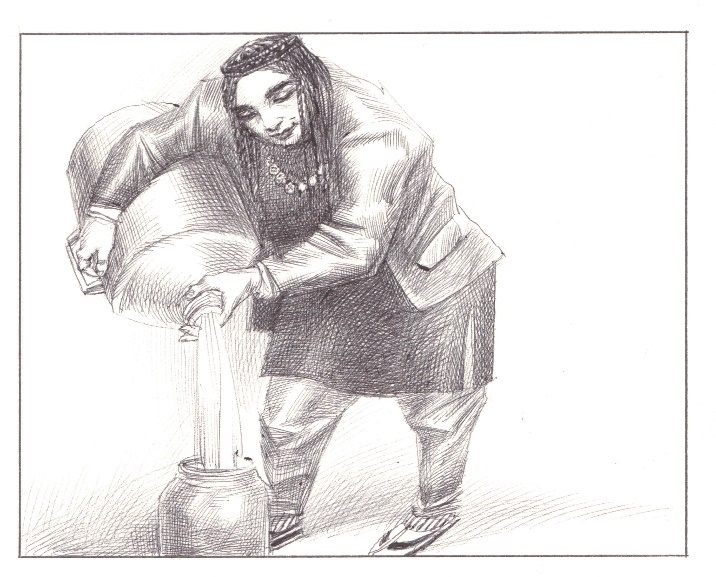

“Mi-i-il-k! Sweet and sour mi-il-k!” A melodious voice was heard ringing outside the veranda window. It was the milkwoman Faruza, an old acquaintance. It was not even eight in the morning, but she showed up like clockwork on Sundays. Emma and I dashed after Mama, racing each other to open the door. Here she was on our doorstep, with her amiable face and dark weather-bitten cheeks. She effortlessly set down her very heavy milk cans – it must have been really hard to carry then all over our neighborhood on foot – and greeted Mama, “Yakhshi mi siz, opajon?” I loved to watch Faruza pour milk neatly into the one-liter jar provided by Mama. She did it so adroitly that a steady stream spurted into the jar, and not a single drop was spilled. The milk can seemed so light in her hands, but I knew that I would not only be unable to lift that rock but wouldn’t even manage to move it. Faruza-opa reminded me of the Bagdad oil sellers whom I had read about in a book about the Medieval Middle East. They poured oil into vessels so skillfully that a ring placed on the narrow neck of a clay jar would remain clean…

After pouring the milk, Faruza smiled tenderly at Emma and me. She loved children; she herself had many.

“Do you like my milk?”

We nodded hurriedly. We liked the milk and we liked Faruza. Her jet-black hair was plaited into many braids that hung down her dark-green velvet jacket, her bright wide silk pants were tied at the ankles, revealing slippers she wore without socks. As to her milk, Mama thought that Faruza’s cow gave the most wonderful milk. We agreed with her. Mama would boil the milk, put a pot in the fridge, and in the morning, it would be covered with a thick ivory-colored skin – cream. Nothing in the world was tastier. And how beautiful the skin was, how rhythmically it swayed on the surface of the milk. It was a pity to touch it, but acute desire surpassed pity. The cream skin was mercilessly broken and put into bowls. Ah, how fast it disappeared into our mouths along with pieces of bread.

“Shall I pour more milk? Do you want more?” the temptress asked, filling a jar. She could read perfectly well what was written on our faces. Faruza was tactful and understood everything – after all, Mama was not made of iron.

Then, the milkwoman was gone, and her milk can could be heard rattling on the next floor. “Sweet, sour mi-il-k!” echoed through the stairwell.

The door had just been closed when another knock was heard. This time it was the plumber, Uncle Tolik. Mama had asked him to fill the crack between the edge of the bathtub and the wall. Emma and I, naturally, forgot about that traitorous crack while taking a bath, and we usually stepped out of the bathtub, not onto the floor but into a big warm puddle, in the middle of which the colorful wet mat, looking like a little island in a bog, made squishing sounds.

Potbellied Uncle Tolik bent over the bathtub, groaning. Even though he was not yet forty, he was rather clumsy because of his corpulence, and he often couldn’t reach the right spot because the bathrooms were not exactly spacious. Light-haired Uncle Tolik had a very kind, round face. If Mama had asked him to get under the bathtub and fix the pipe, I thought, looking at him, he would have done it, but he would certainly have got stuck there… Uncle Tolik’s legs would stick out from beneath the bathtub, and he, lifting the bathtub on his fat belly, would unscrew the drainpipe as the puddle near the tub grew bigger and deeper. The ship of the bathtub would float, rocking on its waters. Uncle Tolik would no longer be Uncle Tolik but a whale on whose back, or whose belly, it made no difference, that ship would be sailing. Emma and I would be on that ship, asking, as we squealed with delight, “Uncle Tolik, let’s go to Africa! Please, to Africa to visit Doctor Doolittle and the hippopotamuses!”

This time it was much more mundane. Uncle Tolik fixed the crack and the broken faucet. Mama paid him.

“Soon it will be cold,” she sighed, counting out some rubles. “Will we have hot water?”

“I don’t know, Ester dear. They’re planning another repair in the boiler room.”

“In the winter?” Mama was terrified. “But does that mean we won’t have heat for two months again?”

“Does the management care? They’ll have heat.”

After expressing his opinion about the management, the plumber left. Mama called us to have breakfast.

Our kitchen was small, but a table for two fit into it. Emma and I sat down at the table, and Mama served breakfast – sweet cheese curds with raisins. Mama cooked very well, but for Emma and me, none of her culinary miracles compared to the sweet vanilla cheese curds from the dairy store. Those cheese curds were the most desirable and delightful delicacy. The smell of sweet cheese curds mixed with vanilla was wonderful. Its whiteness speckled with dark raisins was beautiful. And the taste was superb.

Mama cut the cheese curds and put them into bowls. Emma grabbed her bowl and examined its contents, comparing it with mine – what if Mama had divided it unevenly and I got a bigger part? Her inspection was successful. We ate slowly, savoring each piece, trying to prolong the pleasure.

Meanwhile, Mama appeared behind Emma holding a comb. The kitchen was certainly not a beauty salon, but it was so difficult to comb Emma’s curls that she needed to seize the proper moment to do it, like now, when Emma was enjoying her cheese curds and was willing to put up with any torture, even that one. Her very thick chestnut hair became so tangled during the night that it would have been easier to cut off some of the little knots than try to comb them. But Mama handled the comb skillfully, patiently combing out one strand after another.

“More!” Emma demanded, licking her bowl.

“Please, give me more,” Mama corrected her. “Don’t forget that you’re a big girl. You’re five.”

Emma repeated her request, and she got a second helping. There wasn’t enough cheese curd for me to have more, though I received a tender glance from Mama. It was more than a glance. That expression on Mama’s face could assuage all my sorrows and quiet my whims. The corners of her lips rose in a tender smile, her thick brows merged into a smooth wave… “She’s just a little girl, son. We must forgive her.” That was what her glance and her face conveyed, as if unifying us in our concern for Emma.

It was all right. I would be able to settle scores with my little sister later. Meanwhile, she was enjoying her second helping, and Mama ran her comb through Emma’s now obedient curls, taking fluffy little balls of hair off the comb and setting them on the windowsill. Was it possible, I thought, that Mama would style Emma’s hair in a hair bun one day? Oh no, that wouldn’t be at all becoming on Emma. Mama was a different story… And I squinted, trying to imagine how unattractive my little curly-haired sister would look with a bun at the back of her head.

They both finished their work. I awoke from my reflections and suddenly noticed that my sister was smacking her lips as she stared at me. Why was she staring? Did I look like sweet cheese curd? Oh, well, let’s do it.

It wasn’t the first time that we played the game – who could out-wink whom? Emma always lost, but she often seemed to forget that. I usually didn’t perform my principal trick right away. At the beginning, everything seemed quite innocent – first I squinted, then, quite the opposite, I stared wide-eyed so that my eyeballs almost popped out of their sockets. I followed that by glancing all the way to the left, then to the right, then up and down and finally rolling my eyes. And could she do that? Yes, Emma could, and she obediently repeated everything after me. I was about to reach my goal. I began to flutter my lashes very fast. Emma did too, but it wasn’t easy for her. And then I resorted to my foolproof move – I began to wink one eye at a time. That was what Emma couldn’t do at all. She squinted, winced, moved her nose, even her upper lip, all in vain. Oh, what despair was reflected in her face! That was what I had been waiting for. I even knew how it would end. Emma jumped out of her chair, stomping her feet and squealing. And it was quite a squeal! She didn’t just squeal at the top of her lungs. Her squealing was so loud, piercing and continuous that it must have been heard all over the building.

All little kids go to great lengths to get what they want. But my sister had extraordinary abilities. She outdid all the girls in our building with her squealing skills and her loud voice. I thought about it as I savored my victory. Of course, I felt a bit sorry for my little sister. It wasn’t difficult to quiet her down. All I would have to do was pity her, hug her, and kiss her on the cheek. She was such a sneaky thing. Did that mean it was I who had to apologize? No way…

So, I sat there as if nothing had happened. Why was she doing it? Had she gone out of her mind? Had she had too many cheese curds?

I just sat there shrugging my shoulders and looking innocently at Mama, with the smile of a tolerant grown-up on my lips, “She’s just a little girl. We must forgive her.”

Chapter 22. Once in the Evening

It was the day before that evening, which I thoroughly enjoyed. And the evening was simply wonderful.

At first, I sat drawing on the veranda. After placing a sheet of paper on the windowsill, I began to draw snowflakes. I was using a thick red pencil with a soft waxy core. It was a wonderful imported pencil. The snowflakes turned out so beautiful.

“What are you doing there?”

It was Dima calling to me from outside.

Our verandas shared a common wall so Dima, who lived in entrance number six, was my closest neighbor. That was why we were almost friends, even though Dima was three years older than I. Besides, he had reason to act important – his father was an officer.

“Look,” I said proudly, showing Dima my artwork. I had to bend over and lean out of the window frame. “Look how beautiful it is. Do you know why the color is so bright? It’s because I moistened the pencil with saliva.”

My achievements in the field of fine arts didn’t impress Dima. Quite the contrary, he grimaced as if he had seen something disgusting.

“Aren’t there better things to do? The weather’s so nice. Let’s go play officers.”

The weather was really splendid. It was autumn. My first summer vacation had recently ended. The unbearably hot summer days were also over. The sun no longer scorched from its zenith. Its light was mild and gently embraced everything. It was certainly a day to be outdoors.

I sighed. Mama was working the second shift, Papa was due back home at eight, and it was close to five now. That meant I would have to stay locked in the apartment for three more hours. Emma and I were forbidden to go outside when out parents weren’t home.

“I don’t have the keys,” I informed Dima sadly. “And Mama locked the lower lock.”

“What floor do you live on? Have you forgotten?”

Of course, I hadn’t forgotten. I had climbed out the veranda window many times; it wasn’t difficult. Something else was bothering me – how was I to deal with Emma? She was also at home. Of course, nothing would happen to her. She could stay home by herself. She was a big girl. But the little tattletale would tell our parents about it.

I stood on the veranda pondering the situation. Kids’ voices and laughter could be heard from the street. They were getting ready for the game.

“Well? C’mon!” Dima urged me.

So I made up my mind. After casting a furtive glance at the door of the room, I put my leg over the window frame. Dima stood by, raising his arms. At that moment, Emma darted out onto the veranda.

“I’ll tell Mama everything! I’ll tell her!” she yelled, hopping around. Her short dress inflated like a little parachute, her curls bounced, her eyes sparkled. It’s amazing – why do girls enjoy tattling so much?

Hanging onto the window frame outside the window, I shook my fist at my sister and jumped down. Let her yell for a while; she would soon get tired.

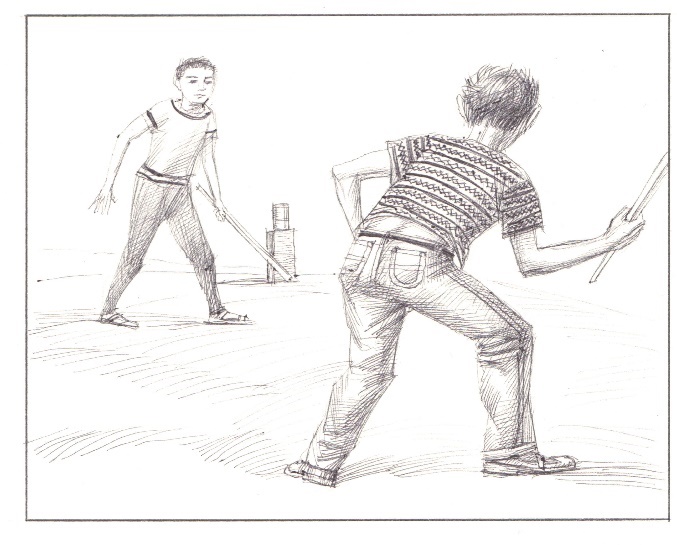

I fumbled around in the bushes near the vegetable garden and extracted a good, well-polished stick, straight and with no hidden splinters, exactly what was needed for playing officers.

Not far from the entrance, on a site beyond the sidewalk, everything was ready for the game. Seven parallel lines, approximately two meters from each other, had been drawn precisely and clearly. The first one was marked “Soldier,” and each subsequent line was marked with the next military rank, ending with General. The goal of the game was to reach the highest rank. There was a tin can placed on bricks in front of the General line. If you knocked it off with your stick and returned uninjured from the battlefield, you attained the next rank. Boys are real masters at devising complicated military games. Battered knees, bruises and other injuries don’t scare anyone. They only bring fame.

Ten boys from our building and the neighboring one lined up on the Soldier line. We had to select a guard whose job was to protect the tin can. He was an important figure, a dangerous opponent to those fighting for higher rank. And he was selected the same way, by knocking the can off. The one who knocked it off immediately avoided the hard and unpopular role of guard.

“I’ll knock it off with my first throw!” My pal Vitya Smirnov took aim. Holding his stick, he drew his arm back… and threw. No, he was not up to it. The stick flopped onto the ground two meters short of the tin can. Poor Vitya was very annoyed. The farther a stick was from the target, the greater chance one had of becoming the guard, and no one wanted to be the guard.

“Look out!” Oparin roared. He failed to knock the can over, but his stick fell closer to the target. Vitya’s shot was the least successful out of the ten, so he had to take his post at the tin can.

And then the battle broke out.

We all lined up at the starting point on the Soldier line. Stick after stick was thrown, but the can remained on the bricks, as if bewitched. That time, I was lucky. Beside myself with delight, I watched as the can flew about seven meters from the bricks, but I had no time to enjoy it. All the boys darted forward with wild cries, overtaking me. “Hurray, hurray!” Now, each of us had to retrieve his stick before the guard could return the can to its place. Anyone who failed to do so would be in trouble, because as soon as the can was in place, the “close combat” would begin. Vitya Smirnov was leaping around the can and, like a pack of wolves, we surrounded him. His task in this combat was to graze at least one of us with his stick. Retrieving one’s stick was quite a feat! If Vitya managed to graze someone with his stick and then knock the can off, he would be the winner. The one who was grazed would become the guard. Our objective was to dodge, avoid being grazed, and knock down the can, leaving Vitya at his post as guard.

The close combat was a picturesque and noisy show. It might seem to passersby who were unfamiliar with the game that we were having a real brawl and that they should let our parents know about it or even inform the police. As we got carried away, we screamed like madmen and brandished our sticks so hard that we brushed them against each other, screamed in pain, swore at each other, crossed our sticks and raised columns of dust.

“Hey, Kolya, be bold!” Oparin yelled at Kolya Kulikov.

“What a goat you are, Sturgeon! Protect me when I attack!” Sipa instructed his partner Server, nicknamed Sturgeon.

“Where are you aiming your stick, you macaque! It should be between the legs!” Server, in turn, reproached Edem, the third member of their unit.

Listening from a distance, one might think that different types of animals who had mastered human speech were shouting to one another – sturgeons, goats, macaques. Who said there was no zoo in Chirchik? Of course, there was, and the most diverse in the whole of Asia.

We all grew tired. We were covered with sweat, bruises, dust. Vitya Smirnov proved to be a mighty fighter, a staunch guard of the tin can. Beaten, bent up and full of holes, the condensed milk can seemed unattainable under the protection of his widely spread legs. But suddenly, an ecstatic roar was heard – it was Oparin who managed to knock down the can. Another ecstatic roar – Edem kicked it once more. And finally, to top it off, I sent the can flying out of the battlefield.

We played Officers until it began to grow dark, and parents could be heard calling their kids home. At that point, I suddenly remembered Emma. It was time to go home, the same way of course.

Vitya Smirnov, who hadn’t yet forgotten that we had been adversaries during the game, nonetheless agreed to help me climb onto the veranda. I climbed onto his back. Vitya groaned. After I got hold of the window frame, I whispered, “Thank you, Vitya. So long.”

Emma, though she was glad I was back, began to tease me again about how she would tell on me. It would be best to put her to bed before Father showed up. After having dinner and washing, we went to bed. I began to doze off right away. Our battle sticks flashed before my eyes as my sister’s squeaky voice was heard:

“Vale-e-ry-y!”

Uh-oh, there she went. My moment for revenge had arrived. I wasn’t even sleepy any longer. Now I’d teach this tattletale a lesson.

Emma was afraid to fall asleep alone, and she often asked for permission to climb into my bed. Usually, I let her. But today…