полная версия

полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

“Well, eagles, how are your labor achievements?” He asked with his special directorial voice.

Unlike Anton Pavlovich Chekhov before him, who assumed that everything about a human being should be wonderful, our Boris Alexandrovich thought that everything about a man had to be domineering, stern and tough if he was a school principal. Before Boris Alexandrovich began working at our school, he had taught soldiers, so he was like a drill sergeant. Besides, he taught social sciences, which meant, he believed, that he was an apostle of Soviet ideology. In a word, he wanted to be a lofty authority.

Quite recently, our principal’s authority had been rudely undermined, which was attested to by a large crimson-blue bruise under his left eye. Some tenth graders and their friends had punched the principal in the eye.

Three days before, late at night, a group of motorcyclists arrived at the school building. The guys thought there was nobody at school, so they decided to ride around the spacious schoolyard. They roared around the yard, stepping on the gas, yelling and laughing. And then, the principal walked out into the yard…

There’s no need to explain how he behaved, what expressions he used to tell the guys to get out of there immediately. The tenth graders were insulted. On top of that, they had long dreamed of settling scores with the principal for all sorts of offenses. I don’t know for sure how many of them took part in the retribution, but two tenth graders were the first to punch the principal. They were expelled from school the next day.

They were expelled all right, but the whole school was delighted to discuss how great it was that the principal had been taught a lesson and to gaze ecstatically at his black eye. We noted with malicious pleasure that our high-ranking administrator had become a bit more polite, more courteous, and, speaking in contemporary language, tried to be more democratic.

So now, he entered the workshop, with a sort of amiable smile on his face, which seemed totally unnatural when combined with the black eye and the commanding voice. Piece of Iron ran hastily into the workshop right after the principal.

“Well, what are we sawing here?” Boris Alexandrovich asked. He stopped near Vova Yefimchuk and began to scrutinize a detail. “How do you like that! What star are you cutting out? Is it Israeli?” And the principal chuckled and looked over us as if inviting us to make fun of it along with him. Piece of Iron joined him, even though Boris Alexandrovich was laughing at his assignment.

When the principal entered the workshop, the screech of files became louder – we were demonstrating our industriousness to him. But, after hearing his joke, many students turned toward Yefimchuk. The latter had taken the ugly-looking plate out of the vise, and the principal was now turning it in his hands, repeating “It’s just like an Israeli star.”

Something inside me snapped.

Whenever the word “Israel” was mentioned – on television or radio, in newspapers, at meetings or rallies, it sounded either malicious or mocking, not like the names of other countries mentioned –say Hungary, Yugoslavia, Egypt… Those were countries, but Israel… Israel was the symbol of everything bad. Israel was an invader, an aggressor, an instigator, which was clear from its very name.

If something undesirable happened in some country, if that country, from the point of view of the Soviet leadership, held a wrong position or even committed criminal acts, its rulers, not the whole country, were blamed for it. The leaders acted villainously in Chile, in the USA, but the people were victims; the people were absolutely not guilty. But not in Israel! The “people” did not exist in Israel; the people were Israel. The whole country propagated extremism and violence and dreamed of conquering the whole world.

In a word, the Jews lived there. And all of them, to a man, were disgusting.

That was the most offensive thing.

The noise of filing died out. The class was laughing loudly. Why and at what I didn’t know, but everybody laughed.

And I continued to saw… I bent over the vise, pushing the file down as hard as I could. I didn’t want to look at the principal: it seemed to me that he was laughing at me. After all, I was Jewish, the only Jew in this class. He surely knew it. So how could he… I didn’t want to look at anybody because the guys were laughing too. They knew I was Jewish, that I was right there, and they laughed. Had they forgotten about it? Did they do it deliberately? Was anyone looking at me?

“Are you actually supplying the whole Israeli army with nameplates?” the principal was having fun as he now addressed Piece of Iron. He was sure that the popular subject he had chosen for his quips would meet with approval, and he had been right.

No one worked but me. I bent even lower over the vise. I was choking with pain, humiliation and anger.

The class was laughing loudly, and the sounds of their laughter blended with the piercing grinding of my file, the grinding of metal against metal.

Chapter 58. Our Friends the Musheyevs

“Amun! Aren’t you ashamed, Amun?”

Those words were addressed to my father. Amun, not Amnun – that’s how his name was pronounced by Aunt Maria, Maria Musheyeva. She swallowed the “n” in the middle of his name. Now it was particularly noticeable for Aunt Maria cried out Father’s name. As she always did at moments of anger or sorrow, she spread her arms, raised them with her palms up and bent her head to her shoulder.

That very Amun had just hurt the feelings of her best friend, his wife Ester, at her table during a dinner to which the Yuabov family had been invited. And it was not the first time.

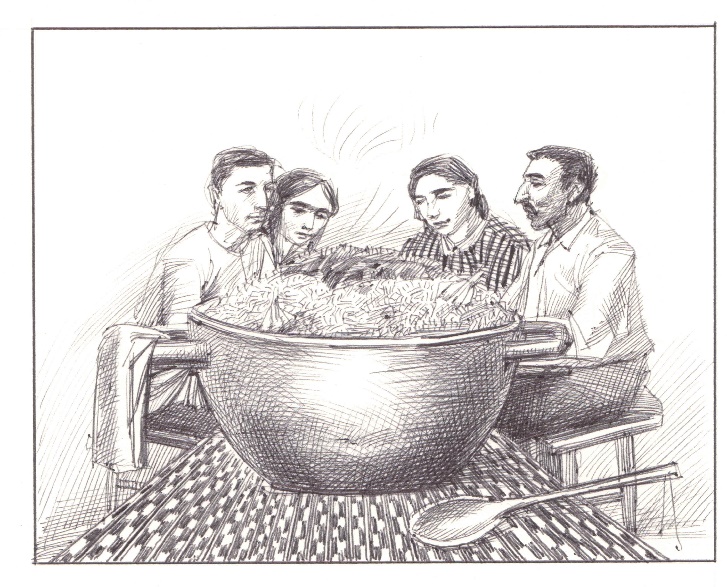

Today, Maria had served an especially delicious sirkaniz, something like pilaf, except with peas. Father stretched his hand toward the langari, the big platter, from which we were all eating, and said:

“You cook so wonderfully, Maria. Teach her how to cook,” and he motioned his head toward Mama.

That’s when Maria flared up.

“Amun, how can you? As if Ester’s cooking is worse. We’ve had dinner at your place many times!”

“Amnun must have cooked sirkaniz,” Uncle Yura, Maria’s husband said, trying to turn the conversation into a joke. “Amnun, is it you who keep house? Tell us, Ester.”

Both Father and Mother were silent. Mama could have answered Uncle Yura’s joke with a joke, but too many insults had piled up. It had been a few years since Mama had stopped tolerating them. If it happened at home, she answered Father, sometimes quite harshly, but only at home, never when visiting somebody. She remained reserved in her Eastern special way.

As for Father, he simply couldn’t shift easily to a different mood. He was silent, his lips twisted, which was what he did whenever he was angry or confused. What a strange man he was! He knew well that the Musheyevs would not back him up, that they would stand up for Mama without fail. Neither Aunt Maria nor Uncle Yura could bear Father’s rudeness. But he acted tough over and over again. Rudeness with respect to Mama had become so much of a habit with him that he couldn’t restrain himself, even in public. It was impossible to anticipate at what moment or why he would attack Mama. It was also impossible to know how he would do it. In a word, Mama was always tense in Father’s company, even when they were visiting somebody.

The Musheyevs were old friends of our family. We had become friends six years before. Once, at the beginning of September, as I was returning from school, I found a little black-haired boy, a bit younger than I, at our place.

“Meet Edik,” Father said. “He’s our new neighbors’ son. Help him. He just started first grade.”

I was flattered to help the first grader. I had already started third grade. Edik made himself comfortable at my desk and opened his alphabet book. The words, divided into syllables, were printed under a colorful drawing on the page: “DA-SHA, LET US GO HOME.” I was happy and even got excited: it was a familiar page. Once, I had also sat at this desk and read a syllable at a time about Dasha. I cleared my throat and said, “Let’s do it.”

Edik, who was the eldest of the Musheyevs’ three sons, and I and our parents soon became friends, though the real friendship, in the true sense of the word, a true closeness, sprang up between the women.

It might seem strange at first glance: my mama and Maria were so different in both their fates and personalities. Mama was taciturn, withdrawn, even distrustful. She couldn’t and didn’t want to tell people about her sorrows – how her married life had turned out or our financial difficulties. Aunt Maria was talkative, open, sincere, and if she befriended someone, she did it with all her heart, generosity and kindness. For her, friendship was not simply spending time enjoyably together; she was always ready to help, to take a part of her friend’s grief and worries upon herself.

Peace prevailed in the Musheyev family. I never heard Yura and Maria quarrel or hurt each other’s feelings. Yura was kind and generous. And this family lived in comfortable circumstances, which neither my poor Mama nor we kids could even dream of.

It’s funny but, perhaps one of the things that brought Aunt Maria and Mama together was exactly that wellbeing, or rather how it had been achieved. Just don’t assume that Mama was looking for wealthy friends. No, that was not the point.

The way in which Yura Musheyev achieved wellbeing was quite Soviet. He was engaged in a business which, in itself, opened up great possibilities and profits, particularly in the field in which Uncle Yura was involved: confectionary products. All the ingredients used to make them – sugar, butter, flour, and so on and so forth – were those very “possibilities” that Uncle Yura used quite extensively to arrange his own underground and very profitable business.

Why do I call that the Soviet way? Because in the Soviet Union, at least in our republic, practically everybody who had access to material of value stole, with rare exceptions. And that didn’t mean that the hundreds of thousands of people who did it were perverted or had an innate tendency to steal, or that poverty and a desire to live better prompted them to do it. I think there were other aspirations that were quite powerful.

Why do people in normal capitalist countries become businessmen? They do it not just for the sake of the “golden calf.” They obviously feel a need to have their own business, to put their creative energy into it, to plan, to live an active life filled with risk and competition. Passionate people, even those prone to risky adventures, often become good businessmen. The Soviet system paid no heed to such traits or needs of human nature. To be precise, the authorities didn’t recognize their existence, and they condemned and persecuted those who tried to implement them. As for officials on different levels who represented that power, they, without ceremony, transferred what belonged to the state and the people into their pockets. Now we know what became of it. But in the past, anyone who wanted to do business, anyone who was eager to have some independence, became a swindler sooner or later.

Yes, we lived in a strange country and led a strange life… It gradually corrupted souls and made the notions of what was good and what was bad fuzzy and illegible.

None of the people like Uncle Yura would have burglarized someone’s apartment or picked someone’s pocket. God forbid! But was it really stealing when someone snatched at least something from the Soviet state that deceived us all the time? The pastries, cakes, and other delicious things were sold to Soviet people at the same prices as at the state stores.

Uncle Yura, naturally, didn’t forget about his family. At their house I had as many sweets as I could wish for. And I could take some home.

Uncle Yura worked in Tashkent which meant that he was often away. Even though their house looked like it had plenty of everything, it seemed empty to Aunt Maria: she was lonely, often, very often. On top of that, she felt fear and tension. If he were caught, he couldn’t expect any mercy. No, Maria, unlike her husband, was not a passionate businesswoman.

That, I thought, was the reason the two women became friends: they were both unhappy. Both of them had something to complain about, something to confess to each other. It was gratifying for both of them to feel a kindred spirit next to them.

Once, arriving home from school, I entered the kitchen where Mama was busy at the blazing hot stove, but it wasn’t just her soups and pilafs that were seething and boiling, Mama was also at the boiling point. I could tell immediately from her voice, her very quick movements. It meant that something had happened. That morning I had heard Father’s voice, or rather his barking, coming from their bedroom.

After she put a plate in front of me, Mama ran out of the kitchen, wiping her hands on her apron, “Eat, I’ll be back…” And I heard her quiet voice from the living room. Of course, she was calling Maria. Whom else could she, seizing a moment, tell about yet another quarrel on the phone?

In America, women visit psychotherapists not just to get medical help. It’s well known that a conversation with an understanding, compassionate person brings feelings of relief and satisfaction.

Mama was back in the kitchen. Her face brightened up. “Have you eaten? Would you like more? Oh, Aunt Maria said that Edik had problems with his homework again. Perhaps, we can visit them together.”

“Aha,” I thought, “Uncle Yura is not back yet, and Aunt Maria is worried.”

The Musheyevs were not only emotionally kind. They knew how we lived, how carefree and selfish Father was. Mama often didn’t have enough money from one payday to the next, and she would run to the Musheyevs to borrow money for a week or two.

“What would I do without them?” she used to say.

Mama well knew how seldom one came across genuine kindness in our cruel world. Probably, the Musheyevs’ support seemed quite natural to me. They were rich, and our life was so hard.

Not that I thought about it all the time. Wealth in the Musheyevs’ house wasn’t that flashy. But I did really envy the Musheyev boys, and I still remember that painful, disgusting feeling.

A holiday was drawing near. Uncle Yura was assigning errands to Aunt Maria when he came to Chirchik for a short time and was about to leave again. “Oh, yes,” he remembered, “what about presents for the kids? All right, guys…” he approached the coatrack in the hallway where his casual pants were hanging and took a few crisp new banknotes out of the pocket. He turned the banknotes in his hands, as if he were teasing the boys, and then gave them to Edik and Sergey. “It’s yours, spend it. Buy whatever you want.”

That’s when the oppressive and shameful feeling of envy, of my own deprivation, gripped me. No, it was even more complex. I felt as if I had been separated from the realm of this wealthy family. I had a different fate and status that my friends Edik and Sergey knew nothing about, which they couldn’t possibly feel and understand.

* * *But that didn’t happen often. I usually felt at home at the Musheyevs’.

We were having dinner, eating pilaf from the big plate. The youngest son, Sasha, was in his mother’s lap. He opened his mouth wide, like a baby bird, and Aunt Maria put pilaf into it, not like a mama bird with its beak but with her hand, and the baby bird munched happily.

“Boys, it’s time to do your homework,” Aunt Maria reminded them. “Valery, will you help Edik? Wait, have you had enough to eat? Would you like some more?” “Thank you,” I shook my head and stood up. It was impossible not to have enough at Aunt Maria’s table, but it was also difficult to stop eating.

Edik, who until now had been eating rather sluggishly, suddenly perked up, and his spoon became busy.

“I’m not full,” he mumbled with his mouth full.

“If you want more, take it from the pot.”

Edik went to the kitchen, and Sergey giggled and winked at me.

“Let’s go. Why should we wait for him? It could take forever.”

Sergey was not lazy like Edik. Even though he was two years younger, he could see through his brother. As often happens, the brothers quarreled all the time. Compared to theirs, my relationship with Yura seemed an example of peaceful coexistence. I enjoyed their fights very much as a spectator.

It would begin with a squabble. The brothers argued about everything. They gradually got fired up, insulting words were brought into play, then their hands began twitching by themselves. The brothers moved close to each other, their nostrils flaring, their eyes wide open and unblinking. One could run through and around the Musheyevs’ apartment, just as in ours. The brothers always used that particular feature of the apartment during their battles. And then it would be best not to get in their way. They could knock you down. I remember how Sergey darted out of the hallway holding a long metal shoehorn during one of those chases. He caught up with his brother on the veranda and… “Boom! Boom! Boom!”

I writhed with laughter because the “booms” Sergey drummed on his brother’s shoulder were so booming, and his brother would forget that he was older and would yell shamefully:

“Ouch! Val-lery! What are you waiting for?! Mama, he’s beating me up!”

Not a day passed without a fight, without new bruises.

* * *After helping Sergey with his homework, I was about to go home when I stopped in the living room to say good-bye to Aunt Maria. Edik was still eating. He didn’t look at me, and Aunt Maria, who looked sad, nodded at me, “Good luck, Valery.”

Aunt Maria was very kind. She was a very patient mother. Was she perhaps much too patient?

Chapter 59. Father and Daughter

Emma broke her leg in class at school, in the P.E. class of Teacher Yuabov, our father, to be precise. Father had transferred Emma from PS 24, which we both had attended, to PS 19 to keep an eye on her all the time for Emma wasn’t succeeding in her studies.

The seventh grade had been jumping hurdles on that ill-fated day. Emma misgauged her jump, and her foot snagged the hurdle. It’s usually the hurdle that falls over, but that time, one of the students accidentally held it up, and my sister fell down.

“He was so mad! You should have seen it, Valery! He was yelling at Bikerova, and she was crying.”

Emma, disheveled and pale, lay in her bed, her left leg, in a cast, resting on some pillows. Only her toes, covered in white powder, could be seen. I nodded compassionately, and my leg began to ache and twitch slightly. I sympathized with Emma and could almost feel physically what she experienced. “A whole six weeks,” Emma uttered in desperation. “I’ll fall behind. I’ll never catch up with them.”

Well, she shouldn’t have despaired on that account. Of course, it was not pleasant to be lame for six weeks, but as to her studies, she had no reason to worry. Soviet schools had a well-organized plan to help students who lagged behind or fell ill. I had also had that experience. And now, almost every day, Emma’s classmates came to our place. They explained the new material to her and helped her with her homework, so she didn’t fall very far behind, after all.

I knew PS 19 as well as my own school. Father began working there when the school had just opened. In summer, during vacation, he often went there to prepare for classes, and he took me along. I remembered the empty gym, the neglected yard overgrown with weeds and prickly bushes. Now, any sports society would have been proud of that yard, which had cinder tracks, soccer goals, and basketball and volleyball courts. The gym was also equipped with every necessary kind of sports apparatus. And all that equipment had been obtained by Father.

Every school in the Soviet Union was a public school so they were supposed to be supplied equally with all the equipment necessary for studies. Well, supposedly… In practice, everything they needed had to be obtained through persistent ordering, by utilizing various personal connections and methods. In other words, if a school had an energetic principle, director of studies, maintenance supervisor and teachers, that school would have either a great physics lab and workshops, or, let’s say, a zoology room and quite decent furniture. If the school didn’t have such energetic people…

PS 19 was lucky: its few teachers were energetic, including P.E. teacher Yuabov. Father was a go-getter; nothing and nobody could stop him. Soon, one could invite spectators to the school’s sports fields.

Father was also a successful teacher, but he was particularly good as a coach. Two of his students became Olympic athletes. The school was famous for its basketball team.

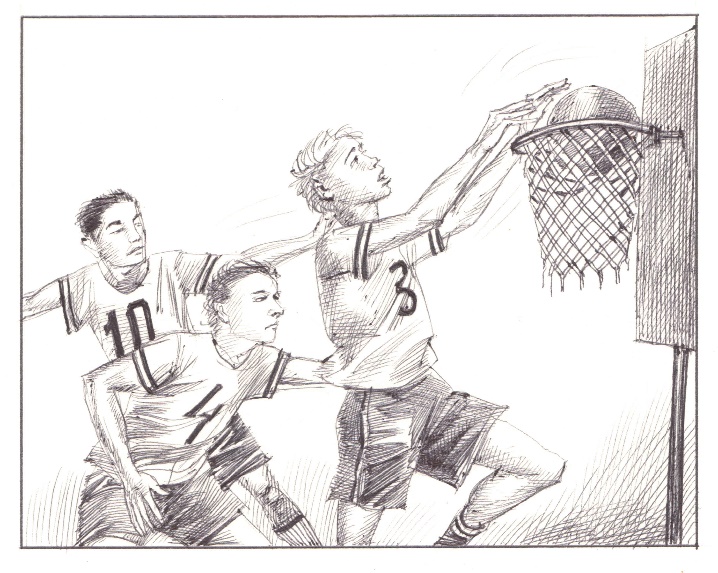

Sometimes, I attended his training sessions. I would sit on one of the benches in the gym, which was big and light with a very high ceiling. About ten high school students began warming-up at the coach’s whistle. They ran around the gym with balls, passing them to each other, dribbling them around the floor and trying to shoot them into baskets. The dribbling sound was constant with muted echoes as the ball moved from one student to the next. The sound of its bouncing reverberated through the air, mingled with other sounds. Sneakers squeaked and tapped. The backboards, to which the basketball rims were attached, quivered and rumbled slightly. The windows rattled. And the loud, overbearing commander’s voice rang out over that symphony: the voice of the coach, my father.

After a few minutes of that, it would seem to me that I was in the thick of a battle, with cannons thundering, and a brave general, fighting alongside his soldiers, commanding them. And that voice, of which I was so afraid at home – and sometimes even hated – that disgusting, rude, quarrelsome voice sounded quite different here. I just wanted to keep hearing it. I rejoiced. I was filled with pride. Yes, yes, I was proud that he was my father. Was it just vanity or were there other feelings dormant in me? Was it a need for love?

Father managed to comment and direct almost every movement of the players. He shouted through hands shaped into a megaphone, not stopping for a second.

“Hot Dog, where are you going? Go to a different corner… Hairpin, pour it, pour it! Pot, drown it, quickly! Okay, okay! Saucepan, draw it! (In Father’s jargon “pour it” meant “throw the ball into the basket.” “Drown it” meant “attack, steal the ball.” “Draw it” meant “give that ball away, pass it.”)

The veins on Father’s neck became taut and blue, dense nodes of bulging veins. His face was almost motionless, very concentrated but not too tense. All the tension seemed to be focused in his eyes. However, sometimes, if someone committed a very serious blunder during a game, Father’s face would become flushed. And then Hot Dog, Pot or Saucepan, whoever was the guilty party, would get it.

The nicknames Father gave to the players were, for some reason, related to gastronomy and the kitchen.

The town authorities praised the school for its sports achievements. The basketball team distinguished itself not only in our town but also in the Republic. The more it was talked about, the higher Father’s prestige rose. The school principal, an elderly Korean, Nikolai Lukich, satisfied all Father’s requests and turned a blind eye to many of the deeds of the school “sports leader,” for which he would not have forgiven another teacher. It was not merely that Father’s demanding attitude toward his students bordered on rudeness, but he was capable of insulting anyone. Well, perhaps not anyone, but those who were inferior.

Recently, Father had, with great difficulty, obtained some rolls of wire mesh to fence off the sports fields in the schoolyard. A few rolls were stolen one night. The rumor was that they had been stolen by the janitor with the help of some high school students. Father reacted without delay.

“I kicked her in the butt,” he informed Mama with satisfaction that evening. “And I told her exactly what I thought of her.”