полная версия

полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

Unlike Yura, Samik didn’t want to consider this property a joint venture, and he went to visit Uncle Misha. Yura was given a talking to and swore he would never again climb onto the roof, but… Is it possible to list all the vows my cousin has broken?

We lay, pressing our stomachs against the very edge of the roof, and looked over Samik’s yard. It seemed that there was nobody in the yard but the chewing cow. We could hear the bull stomping under the overhang at the wall, but we couldn’t see it.

The branches of the apricot tree stretched very close to us. There was no fruit on the nearest one – Yura had been here more than once. If we could stand up to our full height, it would be easy to reach a branch on which round, golden-yellow apricots were shining. But we couldn’t stand up. We had to reach the apricots lying down.

Yura was the first to begin. Lying on his back, he slowly pulled on the nearest branch, which he had grabbed after raising himself slightly. He pulled and pulled, gradually becoming covered with rustling foliage. Yura crossed his legs and gripped the end of the branch between them. Then he grabbed another branch and pulled it up so that we could pick the apricots.

“Pick them. Be careful,” he said in a hoarse voice from under the branches.

Lying down, I stretched out my hand, my head – like Yura’s – stuck out beyond the edge of the roof, but I couldn’t reach them. I stretched out, taut as a string, as if turning into the pole that we used in our yard to knock apricots off the tree. I stretched and stretched. Not just my hand and head but almost half of my thigh was now beyond the edge of the roof. I got carried away. I wasn’t even afraid of falling.

“Pull it, pull it,” I whispered to Yura.

“Pick them, pick them. I can’t hold the branches any longer.”

But he nonetheless continued to pull them, back and forth, back and forth… The branch bent and swayed, and I grabbed an apricot. The cool, round, heavy apricot was in my hand. There was another one next to it on the branch, and I picked it too. And more, and more… That was a good branch.

“That’s it. Let them go.”

The branches rustled and returned to their proper place.

Sweaty, tired and excited, we crawled from the edge of the roof, covered with torn-off leaves, and made ourselves comfortable, even though the metal roof had already become very hot in the sun.

We were terribly thirsty. I smelled a dense yellow-red apricot with pleasure. Oh, what a scent it had. I sank my teeth into its juicy pulp. And Yura, who did everything faster than I, had almost finished eating his first apricot, smacking his lips.

“They will soon have a holiday,” he said sucking a pit. “They’ll probably be away for the whole day. Shall we?”

I nodded. Of course, it would be even more interesting to climb up the neighbor’s tree. And it would be simpler.

Yura giggled, spit out a pit and threw it over his shoulder without looking at the neighbor’s yard.

“Hey! Who’s there? Are you stealing apricots again?” a familiar voice was heard.

It was Samik. Had he sneaked up on us long ago or had the tossed pit given us away – we didn’t give it a thought. We jumped up and rushed to the hammom. The damn roof accompanied each of our jumps with rattling and shooting. I reached the trunk of the apricot tree. As my feet touched the ground, I was about to say something to Yura when I looked at our porch.

Holding the handle of the door with one hand, the other on her hip – a gesture that expressed the utmost degree of anger – there was Grandma Lisa on the porch. Shaking her head, she looked at Yura, who leaned against the trunk of the apricot tree with an independent and impudent look on his face. Then she turned her eyes on me.

Ah, if only I had Yura’s personality.

Chapter 53. “To Keep You Apart…”

Believe it or not, Robert, Yura and I were sitting at the table having a peaceful breakfast at Grandma Lisa’s house. The general atmosphere was actually more than peaceful; we joked, smiled and talked very animatedly. It was quite an unheard-off scene, and not only because of the recent quarrel with Robert. I couldn’t remember an instance when Yura had eaten breakfast at Grandma’s. But now, everything had changed, thanks to the “long-awaited event.” Robert had become a father.

Yes, two days ago, Mariya gave birth to a son; another bogatyr (ethnic hero) became a part of the Yuabov family. Robert was exorbitantly happy and so proud, as if his firstborn were already destined for a great future. Could he possibly remember the silly pranks of his silly nephews? We had been forgiven, the night show in the yard forgotten.

Grandpa and Grandma also rejoiced. The birth of a boy was considered a blessing in any Jewish family, and Grandma Lisa and Grandpa Yoskhaim were devout Jews.

So, we sat at the table devouring our favorite choyi kaimoki, and Grandma Lisa sat on the couch looking tenderly at her son and discussing the upcoming event with him: the circumcision ritual. It would happen very soon, as soon as the newborn was seven-days old. They needed to think of everything, for many guests were expected.

The celebration, the guests, the sacred ritual – which we thought was also somewhat indecent – all that was certainly curious for us. But Yura, as always, had to scoff. Our new cousin became a victim of his wit simply because he was Forelock’s son.

“We’ll start saving money for a wig,” Yura whispered in my ear as Robert listened to his mother’s ideas about shopping for the sumptuous feast.

“Daddy is a bit bald, so the son will soon be bald.”

I chuckled, almost choking on my choyi kaimoki. Robert turned in our direction, but Yura looked at him innocently.

“We’re discussing whether he will look like you. You are, of course, quite handsome, except for the nose. Nothing can be done about that Jewish nose of yours.”

Robert waved this aside. He wasn’t touchy today.

The breakfast was over. Robert and Grandma left in a hurry. They wanted to visit Mariya, to at least look at her through the window. They would not be able to see the newborn before Mariya was discharged from the maternity hospital. My cousin looked over the empty table. Yura hadn’t had enough to eat and, for him, not eating enough was worse than being hungry. When he was hungry, he at least had hope of soon being fed.

Yura’s eyes lit up – there was a familiar luster to them – and headed decisively for the kitchen where the ZIL refrigerator shone bright white by the door.

That refrigerator had served Grandma Lisa faithfully for many years. It was the only one of Grandma’s belongings that hadn’t assumed any of her features. It probably felt that it didn’t belong to Grandma alone but to the whole household. Did it consider itself an animate being because it regulated the work of its own motor? Who knows? Actually, the refrigerator really did resemble an intelligent and amiable being. The inscription “ZIL” in steel letters diagonally across the door resembled a raised eyebrow. Its door opened and closed without noise, as if it wanted to serve you better. Its engine didn’t puff as it turned on; it worked quietly, tactfully, trying not to bother anyone.

Grandma took such good care of the refrigerator that it might have gotten a swelled head. She washed it like a baby and maintained perfect order on its shelves. A little rag hung from its door handle. Every time Grandma closed the door, she wiped the handle. It made Yura and me laugh: Grandma acted like a sophisticated criminal wiping away his fingerprints after committing a murder.

It goes without saying that no one but Grandma could open the refrigerator. God forbid anyone should take anything from the shelves. There was a strict refrigerator ban for all the members of the household.

And Yura was about to violate it.

“Stand guard!” he commanded.

Grandma mustn’t catch us unawares: she hadn’t left yet and was fiddling with something at the table in the yard. What if she needed something in the kitchen? But there was nothing you could do about Yura.

I took my post at the door, which was ajar. Yura was already digging around in the refrigerator. What was he looking for, I wondered. Each shelf had its function: one was for meat, another for dairy products; there were pickles and preserves on the bottom one. Judging by the clinking of jars, Yura was inspecting that very shelf.

“She thinks she can hide it from me,” he said, removing the liter jar of black current preserves from the refrigerator.

“Are you out of your mind?” I whispered.

Grandma claimed that these particular preserves helped lower her high blood pressure. That’s why she never treated anyone to the black current preserves. She had some when no one was around in order not to tempt anyone. Sometimes, she would have it in the presence of family members, and I was one of them.

Grandma moved the jar closer and ran a teaspoon around the upper layer of the thick, almost black, grainy preserves very carefully. The spoon filled, and the surface of the preserves remained smooth. After she had scooped out enough, Grandma transferred it onto her tongue and savored it with her eyes closed, moaning and rocking her head from side to side. Perhaps she did it only when I was around so I would remember that she was a sick person and ate preserves not for pleasure but for medicinal purposes.

If only she could see how Yura was treating her preserves.

“Is she the only one who has blood pressure? I also have it,” he groaned as he struggled with the tight lid. He dipped his spoon into the jar and almost reached the bottom, making a big hole in the preserves and leaving a wide trench on the side. He swallowed the preserves quickly, and the spoon went in for another serving. After compensating for what he had missed at breakfast, Yura magnanimously held the jar out to me. After I had a couple of spoonsful of preserves, I repaired all the damages – I cleaned the sides of the jar, leveled the surface and closed it up tight.

“Do you remember where it was? Put it there.”

We wiped the handle of the refrigerator with Grandma’s rag, which was quite appropriate this time.

* * *Grandma was still busy at the table in the yard. There were large pieces of meat, just washed under the faucet in the yard, in front of her. Now, she salted each piece, which one needed to do a few hours before cooking. Then she transferred it to a big enamel basin. After putting another piece into the basin, she covered it with a wicker tray to keep flies away. She finished her work, placed a heavy stone on top of the tray to keep cats away and went inside to change.

“We’re leaving. Stay home!” she ordered.

That quite suited Yura and me.

Morning was almost over, and a sultry day was setting in. The tulle curtain on Grandma’s door didn’t puff up like a sail; it just quivered slightly. The hens were hiding under the eaves. It was time to refresh ourselves.

We were allowed to use the hose to cool off only if we didn’t use it too long and didn’t make too much noise. That’s why we were glad that Grandma was leaving. Otherwise, she was always running out onto the porch yelling, “That’s enough! You’ve flooded the whole yard!”

We hadn’t taken into account that another adult was at home: Misha, Yura’s father.

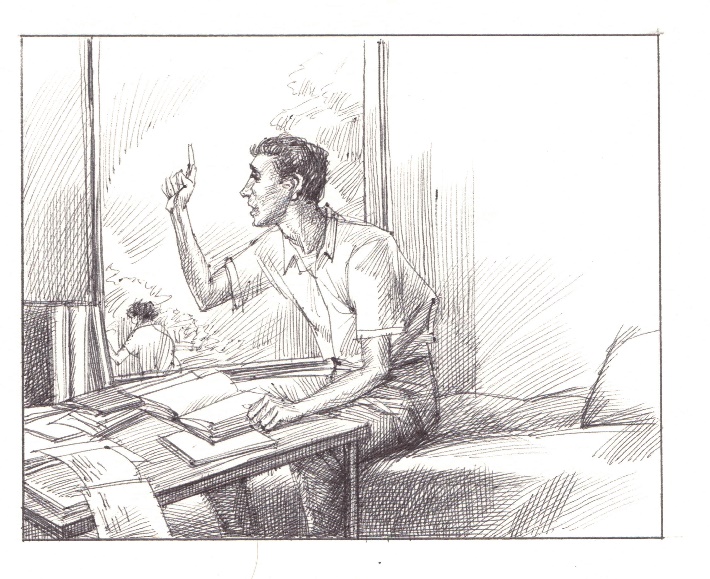

This summer, Uncle Misha was getting ready for exams in physics at the graduate school, and he was finishing his thesis. He studied by correspondence and was supposed to defend his thesis in Moscow. Now, Uncle Misha studied day and night before the decisive storming of the fortress called “master’s degree.” It was common knowledge that no Jew could defend a thesis and get a degree, even if he was brilliant. Uncle Misha spared neither time nor effort. Sitting in his study, he read out loud and committed to memory all the valuable information he planned to incorporate into his thesis dedicated to liquids and their properties. His well-trained teacher’s voice coming through the open window resembled the voice of an announcer giving an endless report on the radio. As we made our way past that window, we giggled quietly. We were going to conduct a practical study of the properties of a liquid called “water.” Should Misha watch us and use a few things from our experiment in his work?

Well, we weren’t going to invite him to watch. On the contrary, we warned each other, “Don’t yell. If he hears us, we’ll get it.”

The hissing and gurgling began in the faucet, then snorted as water filled the thick rubber hose and gushed, dousing the dried-out wooden gate. Sprayed with water, it looked cool. The poor thing must have been glad. We always doused ourselves at the gate, and we always shared with it the pleasure of a cool shower on a hot day. Yura would douse himself until late autumn. He was a real walrus. Neither shooting cats with a slingshot, harassing Forelock, nor even a delicious dinner – nothing gave him more pleasure than cold water.

Of course, Yura was the first to be hosed down.

“Don’t forget my head! Start with my head!” he yelled jumping under the stream.

As if I didn’t know. Yura pressed his hands to his chest and leaned his head way forward, and I directed the stream right in his face.

“A-a-a-a-ah!” a long, triumphant, ringing cry was heard. It’s amazing how much one can express with just one sound. I pressed my finger to the end of the hose, and the pressure became even more powerful. Doughnut turned into a top. His solidly built, shiny little brown body, his bottom wrapped in short underpants flashed by. My cousin had a great suntan. Unlike me, he never got sunburned. His suntanned face turned up, his white teeth sparkled and clicked slightly. Yura resembled our Jack at such moments. He also turned and clicked his teeth when he was ecstatic. It seemed as if Yura had shaken himself out, as Jack did after washing when water would also fly in all directions, as if from a fan.

Yura’s shower could last forever; he was insatiable and failed to remember that I wanted it too. But, after all, I also had a nice entertainment: lashing my cousin with water as if with a whip.

Yura and I had been friends from as early as we could remember. Naturally, we quarreled quite often, usually through no fault of mine. Yura had a more explosive temperament. He was the first to attack, but now the initiative was in my hands, literally. I could get even with him for old offenses, so I tickled Doughnut under his armpits, on his neck. I spanked him on the butt with the stream using it like a koshka-devyatikhvostka. He roared with laughter, yelped and dodged. But the merciless stream always found him.

“That’s enough, enough!” he shouted at last. “Now it’s your turn.”

Aha, at last he remembered. He would definitely pay me back, but I had no choice. “Get undressed!” Yura ordered.

What for? I was wet all over anyway. Well, all right, I took off my wet clothes and dashed under the stream.

“Ou-ou-ouch!” I yelled, perhaps, more loudly than Yura, but not from ecstasy. The water seemed ice cold to me. It burned as if I had been stung by a swarm of bees. I choked. I became numb. It always happened to me when I was doused with water or dived into water. Perhaps it was because I was skinny. I jumped away from him, to the gate. I began to whirl, hopping to the left, then to the right, but the ice-cold water continued to lash me. Doughnut knew his job. He laughed loudly, spraying me harder and harder. I was driven into a corner with nowhere to retreat. All I could do was run to another part of the yard, but that would be a disgrace. Then, suddenly I didn’t feel so cold. I had gotten used to it, or the stream of water had warmed up in the sun. The spray had become pleasant. I hopped about, yelling with pleasure, from overcoming the shameful weakness. And Jack, who had envied us for a long time and dreamed of joining us, yelped and barked and rattled his chain. And Yura laughed loudly and yelled, becoming a firefighter who was rescuing a man on fire.

“…immediately! Can you hear me? Stop yelling immediately!”

Uncle Misha stood on his porch. We didn’t know how long he had been standing there yelling. His face was very angry. We had distracted him from his studies. It would be all right if this were the first time. But no, it wasn’t the first time, far from the first time.

“All right…” he said, “we’ll have to keep you apart.”

Yura and I exchanged terrified glances. Robert had said that he would call my father, and now Uncle Misha wanted to keep us apart.

Would they ruin our vacation?

Chapter 54. “A Spring by the Name of Larisa”

The ninth grade. The bell is silent.

A ray of April sun is on the wall.

How long will the lesson drag on.

How long before I get a break…

There was not a single ninth grader in town who didn’t know this song. It was hummed and sung at home, in school corridors, at bus stops, anywhere.

I, for example, was humming it now, not out loud, of course, but to myself because it was happening in class, and that class was dragging on unbearably.

In the beginning, everything was normal. I was in class listening to our math teacher, Nina Stepanovna. I was listening quite attentively and taking notes. And then I looked out the window. My desk was right by the window, which was wide open. And I could see the branches of an apple tree in bloom, which was right near the sports field, and the green velvet hills beyond the sports field through the opening between buildings.

And here that song began to resound inside me all by itself. Perhaps it happened because the song contained the following lines:

And there is spring outside,

A spring by the name of Svetlana…

Those lines turned over and over in my mind, in my soul, but I heard a different name in them: Larisa.

* * *Yes, it was that same Larisa. Ten years had passed, but I had only to look at her, and I was still crazy about her just as I had been in kindergarten. It seemed to me that she hadn’t changed at all. She was still slender with fluffy bows at the ends of her light braids, which trembled slightly as if they were alive when Larisa nodded, nice freckles around her nose, and her sweet shyness and reticence.

Three years ago, when Flura Merziyevna had to leave the school, our sixth grade was disbanded, and all the students were distributed to three other parallel classes. It was sad to part with my classmates, particularly with Zhenya Andreyev and Vitya Smirnov. You get used to your class. It feels like home. But there was something that comforted me – Larisa Sarbash had been moved to the same class as I.

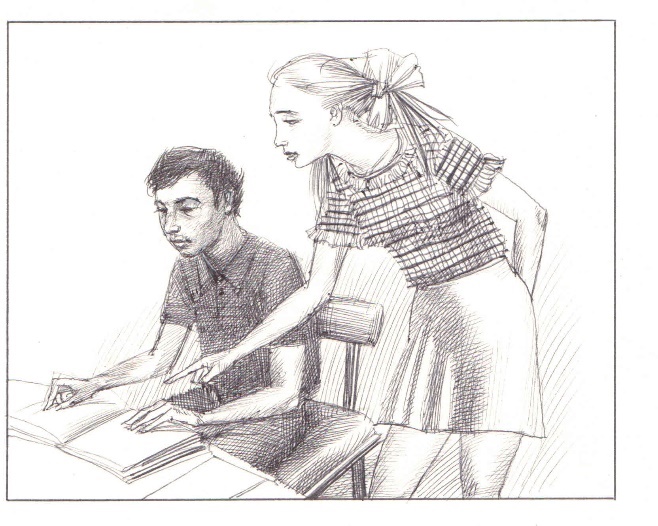

It seemed like some kind of a secret omen. Soon, I got sick and couldn’t attend school for two weeks. Afterwards, I had to make up what I had missed, particularly in math.

“Let’s choose a helper for you,” Nina Stepanovna said, and she cast her eyes over the class. “For example…” “Larisa,” a crazy hope flashed in my mind. “Oh, if only she would choose Larisa.”

“Larisa Sarbash,” Nina Stepanovna said.

It was a miracle. Nina Stepanovna rose considerably in my estimation: she could read minds.

We attended the second session of school, and I would go to Larisa’s place an hour and a half before classes. She sat me down at her desk and, bending over my shoulder, opened a textbook. The chair on which I sat was the only one in her small room.

“What about you?” I asked, moving to the very edge of the seat. Larisa didn’t seem to hear me.

“Here, read this rule,” she said.

And while I was reading, she walked back and forth behind my back.

And I read very slowly, pretending that I was trying to delve into that very simple rule. Good heavens, I had figured out all those trifling rules and problems myself at home long ago. That was definitely not what I came to Larisa’s for. Should I have turned down such luck? So, I did my best to pretend to be a dimwit, and I made mistakes in problems. Then Larisa bent so far over the desk that I could feel her breath and the smell of her hair, passed her pencil over my notebook and explained to me how to solve a problem.

She tied her hair at the back of her neck at home. It fell down her back as a ponytail, and when Larisa bent down, the tail slid across her back to her shoulder and fell forward, brushing my cheek. When Larisa noticed it, she tossed it back with an amazingly delicate, graceful movement of her head.

I liked Larisa at home even more than at school. Her light, colorful short-sleeved house dress was very becoming on her. When she sat down or turned quickly, her dress flew up, revealing her slim graceful legs. If Larisa seemed beautiful to me in her school uniform, you can imagine how she was in her house dress… Ah, I should have been looking and looking at her, but she was walking back and forth behind my back.

Once, Larisa sat down on the part of the chair that I always left vacant for her. Her elbow touched mine, and her head, passing over my notebook – she was explaining something to me – moved close to my fingers. She had such soft skin. And – I don’t know how it happened – I turned my head a bit. Our faces were very close. Her eyes were so blue, so big. They looked at me without blinking.

Suddenly, Larisa said, “You have such long lashes.”

I was so embarrassed and bewildered that I blurted out, “Is that good?”

I couldn’t have come up with anything stupider. Larisa flushed and slipped off the chair.

“Oy, it’s time to go to school.”

We ran to school in silence and walked to our desks. One thought throbbed in my head, “I’m such a fool, a fool, a fool. Why did I say that?” Now and then, I forgot about it, and I saw Larisa’s eyes in front of me and heard her voice, “You have such long lashes.” And I felt so good.

I visited Larisa for two weeks, and we, two teenagers in love, failed to declare our love to each other. We were such a strange couple. I was often timid at decisive moments. Larisa was surprisingly quiet and bashful. You could hardly hear her voice during recess. Other girls chatted non-stop, giggled, shouted to each other, but Larisa was quiet. She never cried out from her seat in class. She didn’t raise her hand when a teacher asked a question. Still, she was a very good student. She was just very quiet. That was what I liked about her. She was special even in that.

It seems to me that the first time I realized I was in love was in the fourth grade. I can envision perfectly the day when Alyosha Bondarev and I walked up the steps carrying rolled-up maps from the school library. Our geography teacher had sent us to bring them over. We were panting as we carried them. And suddenly I made up my mind to ask Alyosha:

“Look… What do you think about Sarbash?”

Alyosha stopped, his eyes shone, his mug looked sly.

“She’s quite a girl. How about you?”

I was silent. Alyosha laughed.

“C’mon, don’t be scared. I don’t need your Sarbash. Larisa’s quite a girl, but I prefer Lucia.”

I was happy. Alyosha was a real friend.

Right after that geography class, we decided to play a game called “the stream” during the main recess. The stream was a game for those who were in love, and we all began to fall in love in the fourth grade.

You line up in pairs. Each pair holds hands, raises them and steps back to form a passage. The one without a partner enters the passage bending slightly, walks down it and, on the way to the end of the passage, grabs someone by the hand. Out of the passage, the new pair joins the line in the back, and the person now left without a partner goes into the passage alone, walks to its end and grabs a “victim.” That’s how the stream is played.

On the day we played the stream for the first time, many secrets were revealed. Then there were fewer of them. Almost each of the boys in class 4B had made his choice. Everybody knew perfectly well what pairs should be expected by the end of the game, to be precise, could be expected. But what if things changed?

The long recess was noisy and resounded with many voices, laughter, and the trampling of feet. And in the midst of all that chaos, eight pairs from class 4B silently played that calm game, similar to an old ballroom dance, by the wall of the corridor.