полная версия

полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

Mama came out to the courtyard.

“Kids, we’ll be eating soon. We just need to buy bread.”

Bread, to be precise, lepyoshka (flat bread) was bought from an elderly Uzbek woman who lived nearby, across the street from the tea house. She baked them in the tandir (clay oven buried in the ground) under the awning. Small, plump, fragrant, with a crunchy crust, they were popular all over the neighborhood.

“Bir sum (fifty kopecks),” the Uzbek woman took fifty kopecks and gave Mama five flat breads that were still exhaling the heat of the oven.

Oh, how we wanted to eat them right away or to have at least a little tiny piece, but Mama shook her head.

“At home, at home, with dinner.”

At home, at the table, Grandpa sang the prayer. “Amen” we echoed, as always. Pilaf was served on a big platter. Dark rice with chunks of meat appeared almost to breathe, exuding steam. Heads of garlic stood out in all their splendor on top of the hill of rice. The adults traditionally ate without spoons. They pressed a small portion of rice with their fingers into the platter and then raised it to their mouths. Grandma served raisins and thinly sliced carrots for dessert.

Unhurried dinner conversation was underway.

“How’s your health, Papa?” Mama asked.

Grandpa only nodded in response. He didn’t like such questions.

“How’s Amnun doing?” Grandma asked.

“I lost my health in combat, and he – on a motorcycle…,” Grandpa meant the incident with which it all began. “Ah, young people, young people.”

“Sugar, and I want butter! Sugar, and I want butter!” was heard from the hallway.

Those words were accompanied by ringing laughter and the snapping of fingers… My aunts, Rosa and Rena, who never missed a chance to tease me, had arrived. I always sang those words, “Sugar, and I want butter!” when I was hungry. After kissing us, Rosa and Rena sat down at the table.

“Have you been to the bazaar?”

“Yes. Everything is more expensive again,” Rosa informed us. “Khurmati doozt (officials are thieves)! They don’t care about people.”

“How are things at the factory, Rosa?” asked Mama.

“They’ve raised the production quota once again. It was high enough to keep up with.”

“I know, I know. Meetings all the time. ‘Sew better, sew more.’ But our rate of pay is the same. It looks like they plan to raise the income tax beginning in May.”

“It’s the same with us – meetings to discuss output and alcoholism. I’m sick and tired of it. I have no more patience.”

“You’d better put up with it because there’s nowhere else to go. It’s the same everywhere,” Mama sighed.

Mama had three sisters and her brother Avner. They were good friends as they were growing up. When Grandpa was sent to the front, Mama was three and Avner was six. Grandma Abigai replaced her husband at his booth, working as a cobbler. Avner, as the eldest child, kept house – he frequented stores and the bazaar in search of food, took care of his sisters and even helped his mother in the booth, where he shined clients’ footwear. Mama told me that once he got hold of two rolls. On the way home, he was thirsty and stopped at a drinking fountain. He put the rolls down, had some water, and then saw that the rolls were gone.

“Valera, Valera!” Grandma Abigai sing-sang my name tenderly. “Oh, djoni bibesh. Ina gri (my dear, take this),” and she gave me a fat juicy piece of meat.

There was no limit to Grandma’s kindness. She always had a gift for her grandchildren in her modest house – be it a homemade toy or some sweets. And she always gave us her smiles.

It seemed to people who knew her that she was a very happy person. But I sometimes saw her and Mama crying together in the back of the house. They were very close, and when they got together, they talked without noticing the time.

“Burma,” Grandma winced as she tried a sour plum.

We often laughed when Grandma happened to put something sour in her mouth. She winced in a very funny way, her thick eyebrows came together over the bridge of her nose, her nostrils widened, but her eyes, on the contrary, became narrow slits, and her lips contorted as if she was about to cry. Even the scarf on her head seemed to wince.

Meanwhile, Rosa teased and tickled me.

“May I eat your eyes? How about your eyelashes?”

Seated next to me, she patted my cheeks and kissed my eyelids. My aunts liked my big eyes and long lashes. It seemed to me that they sometimes played with me as if I were a doll, and I got angry and embarrassed.

“Will you ever talk to us? I know what we’ll do to you. We’ll dye your lashes with usma.”

At that point I naturally couldn’t take it any longer. I broke free of Rosa’s arms and ran away.

* * *Dying eyebrows was one of the favorite occupations of the women in our house.

They rubbed fresh usma sprouts between their palms and squeezed the juice out onto the bottom of a tea bowl turned upside down. Then they applied it to their eyebrows using cotton wool wrapped around a matchstick. Admiring their thick green eyebrows in a hand-held mirror, they repeated over and over, “How does it look?”

When the sisters had a free minute, they would turn on the radio to listen to Uzbek music. It was tender, slow, sad, and it was the only music they truly enjoyed, that touched their souls. The sisters would snap their fingers and rock in time with the music. They would also sing along to the songs they knew.

And Grandma liked to play cards, especially with her children and grandchildren, so she suggested her favorite entertainment. Her eyesight was poor, so she held the cards close to her eyes, squinting at each of them. She clicked her tongue, smiled, rocked from side to side and mumbled, “Ibi basardroya. I na bin. (Damn it. Just look at this.)” She cast cunning glances at us, as if to say, “Oh my, I think I’m in trouble.”

But if someone tried to take advantage of her poor eyesight, it didn’t work. Grandma kept close track, with her watchful eye, of which cards other players put on the table, and if she noticed cheating, she returned the cards to the violators. Grandma was always vigilant.

* * *Our time at Grandpa Hanan and Grandma Abigai’s house flew by. We didn’t notice that it had grown dark. It was time to go home.

We said good-bye. The aunts walked with us as far as the tea house, and from there we walked to the streetcar stop.

“The Turkmen Bazaar,” the conductor announced. We got off, and the streetcar sped away, sparks flying as it left.

It was pitch dark as the sparse streetlights flickered dimly. There was that special stillness that one felt only at night. It was intensified by the rustling of leaves, the peaceful buzz of cicadas, and the sounds made by the tires of rare passing cars.

The Turkmen Bazaar was on the other side of the streetcar track. The huge market, which stretched for hundreds of meters, was silent now. It would come back to life at sunrise.

We walked slowly. Mama was carrying the lightly snoring Emma. It took us twenty minutes to get to Korotky Lane. The bulb above the gate lit the lane dimly. Jack barked gruffly and then felt silent as he sensed us.

Everyone was asleep in the house.

Mama unlocked the door. We could smell the sharp scent of dampness coming from inside. There was a loud click as she turned the light switch. The bright light suddenly illuminated the small room that served as a foyer, kitchen and place to entertain infrequent guests.

“Close the door, Valery.”

Standing on the threshold, I reached for the door handle. Then I looked at Yura’s windows. They were dark… The war game, I remembered. Yura must have waited for me for a long time.

Mama put Emma to bed and lit the stove.

I told her I was hungry. We had had dinner long ago. Mama opened the fridge. A lonely lightbulb revealed its empty shelves.

“It’s late, son. Let’s go to bed,” she said as she turned away.

“It’s all right, Mama. I’m full. It’s late. It’s late,” I repeated, holding back my tears.

Chapter 4. A Little Mouse from a Little Hole

Day was breaking. The first roosters had already crowed. Cows were mooing in the yard next door. Jack was dangling his chain.

“Kids, get up! You’ll be late for kindergarten!”

Mama turned on the light. The bedroom window faced the yard, so the sun didn’t visit us often.

After eating our sweet tea and bread, we walked into the yard. It was the hour when Grandpa Yoskhaim performed his customary morning grooming. With his drawers on and a jar of water in his hands, wearing galoshes but no socks, he shuffled to the wooden outhouse. After leaving the outhouse, Grandpa squatted near the vines and, patting his bottom, did his final thorough washing. Grandpa was very tidy. Following the Eastern tradition, he used only water, and he had an aversion to paper, for he considered it a harmful innovation. Everybody made fun of him saying that the biggest grapes grew where Grandpa washed his bottom. Then, Grandpa began to wash himself. Bending under the water faucet, he soaped his shaven head, neck and hairy chest, and poured cold water all over himself, snorting.

Even though the sight was all too familiar, Emma and I were ecstatic about it every time we saw it.

After saying good-bye to Grandpa, we set out for kindergarten. It wasn’t far – it took just twenty minutes to walk to Little Fireflies kindergarten.

Our group’s room was large and light. Before all the kids arrived, we were allowed to play. Together with my friend, curly-headed Grisha, we tried to catch a spot of reflected light that hopped back and forth on the wall. We failed to catch it. Grisha got angry. He grabbed a wooden mug from the shelf and, banging it against the wall, chased the agile messenger of the sun.

“It’s time for morning exercises!”

Our teacher Maria Petrovna, clad in a neat white overall, tall and gray-haired, was strict, and we were somewhat afraid of her. We took off our outer garments and did our exercises diligently. After the calisthenics, we had breakfast in the spacious cafeteria where each group had its own table, and each of us – an assigned seat.

Grisha and I quietly put crusts of bread into our pockets for we needed to feed our friend. “Little Mouse from a Little Hole,” as we called it, lived near the garbage bin next to the restroom. But we couldn’t visit it yet. Classes began right after breakfast.

We were sitting at small desks. Maria Petrovna began with the usual. “We live in a big harmonious country. What is it called?”

She waved her hands like a conductor, and we shouted, “The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics!”

“And who was this country’s founder?” and, just in case, Maria Petrovna pointed to the portrait of a curly-haired boy, and we shouted as loudly as we could, “Vladimir Ilyich Lenin!”

Grisha was particularly diligent. He loved to shout, and he used every opportunity to do so.

“How many brotherly republics are there in our country?”

“Fifteen!”

“In which of them do we live?”

“In the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic!”

Our harmonious and clear answers would have surprised only a very uninformed person. We repeated the whole thing over and over again very often, day after day.

Then we could play. When the weather was warm, we were taken to the pavilion. Grisha and I exchanged glances – at last! Doing our best not to be noticed by the adults, we ran to the garbage bin. We were agitated. Would Little Mouse from a Little Hole, our little gray friend, show up when we called?

After placing the bread crusts by the wall, we waited patiently for its arrival. And we were rewarded – first a black nose, then eyes bright as cinders appeared in the hole. Another moment, and our mouse ran along the wall…

“What are you doing here all by yourselves?” the voice of the kindergarten janitor sounded like a bolt from the blue.

We ran away as fast as we could. None of the adults knew about our secret friend.

“Has the janitor seen it?” Grisha whispered, his voice trembling, when we returned to the pavilion. “Oh look, she’s coming this way… She’ll tell everybody about us.”

Paralyzed by fear, we watched the arrival of the janitor.

“Maria Petrovna,” she called to our teacher. “They’ve delivered beef to the kitchen.”

“Is it fresh?”

“They say it’s all right. But they don’t have much of it. You’d better hurry.”

“Thank you. I’ll go see them.”

The janitor moved away. It had blown over this time.

Fair-haired Kostya came running to the pavilion holding up his index finger.

“Look what I have. I’m going to trick it now. Ladybug, fly to the sky. Your children are there waiting for the candy you’ll bring them,” Kostya sang.

And the trusting ladybug spread its wings and flew away to look for its children.

After lunch we all lay down on our cots. “Quiet hour” lasted a whole two hours. What a boring time it was. The only entertainment we had was listening to what the adults were talking about. People who worked at the kindergarten usually visited Maria Petrovna while we were supposed to be napping. They would sit in the corner talking quietly. Today, the cook, Zhanna Kirillovna, stopped by.

“How are you doing, Maria?”

“The same old story…”

“Perhaps you should forgive him. After all, you have your daughter.”

“I just can’t take it any longer. I don’t remember when I last saw him sober. There’s not one kopeck at home, and he’s drunk away the television set.”

“Drive his buddies away. Perhaps he won’t drink alone.”

“He drinks with his buddies at work. Can I possibly establish order there? Now there’s peace and quiet at home. No one runs wild, no one curses.”

Maria Petrovna began to cry quietly.

“I know what you have to put up with. It’s the same with mine… Sometimes he gets so plastered. So, what’s to be done, Maria? Men don’t drink because they want to. Life’s hard.”

“Who’s talking there?” the teacher asked threateningly on hearing someone’s whisper. “This is the quiet hour. You must all take a nap.”

“I understand that life is hard,” she resumed their conversation, “but what are their brains for? Our daughter is growing up. Who should she learn from? They should be ashamed of crippling so many innocent souls. Is life easy for women, Zhanna? No, but we don’t turn into alcoholics. No, I don’t want him back. I’ve had enough of him. We’ll manage without him somehow.”

“All right, Maria. God be with you. I’ll go get some beef. Don’t forget to stop by.”

“Alcoholics, alcohol-lics…lics…Cursecursecurse… Don’t want him back,” echoed in my drowsy brain for a long time. Then I fell asleep.

Chapter 5. Happy Birthday, Little Redhead!

That day, as I returned home from kindergarten, I saw Father in the yard. He was sitting on a chair under our mighty apricot tree, his hands resting on his knees. He looked as worn out as he had in the hospital. He was still breathing with difficulty.

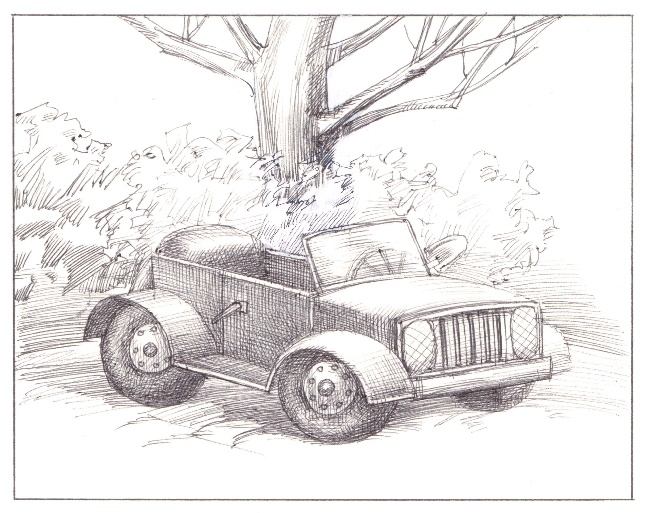

Misha, Yura’s father, squatted next to him rummaging through a nice-looking blue thing. Wow, it was a car! It had wheels! And it was blinking – first its lights lit the apricot tree and the wall behind it, then they went out.

“I need to adjust the contacts,” Uncle Misha mumbled.

Then he saw me, sprang to his feet and shouted his usual greeting, “Look who’s here! How do you do, little redhead!”

Misha always greeted me with enthusiasm, never forgetting to remind me of my former hair color. According to his stories, when I was “little, redheaded and potbellied,” I would walk around the yard with my empty chamber pot in my hands, banging it against the walls. Misha would say, “Look, our rayis is coming,” hinting at my likeness to a local collective farm boss since, as a rule, they were potbellied.

“Happy birthday, little redhead! This is for you.”

Mesmerized, I stared at the blue pedal car in which he had just been rummaging. It had a black steering wheel, seat and wheels, and a blue body. It sparkled and shined all over in its novelty and freshness. And this miracle was mine! And today was actually my birthday – April 7th.

“What do you say?” Mama prompted.

I mumbled “thank you,” unable to tear my eyes from the car. I hardly had any toys, and definitely nothing like this.

Misha picked me up by the armpits and lowered me into the car.

“Vale-e-e-ya! What kind?” he sang imitating Yura and, at the same time, continuing our old game. That was how Misha always asked me about the skeleton of an old car that had long been sitting outside our gate. “What kind is it?” he always asked. And I always answered, “A passedger car.”

But this time my fascination with the present didn’t leave any room for our game.

“Well, little redhead, go!” Misha commanded.

But how could I go if my feet just dangled in the air and didn’t reach the pedals? I was desperate.

“I see,” Uncle Misha obviously hadn’t expected that to happen. “Well, that’s all right. You’ll grow soon enough. Meanwhile, let me give you a ride. Turn the wheel!”

The wheel squeaked, the pedals rattled, the steering wheel shook – I was taking a celebratory ride around the yard. The animals and birds were panic-stricken. The hens cackled in fright. The pigeons took flight. Jack stood motionless, staring at us in bewilderment. Uncle Misha zoomed around with all his might. The cherry trees, the water pipe, the kennel flashed by fast. That was some ride!

As I was having a great time, I heard a shrill shout, “Vale-e-ya!!!”

This time it wasn’t a plea for help. I knew my little cousin well. Everything new that appeared in the yard had to belong to him.

“Don’t give it away,” I commanded myself, ready for a quarrel.

“Yu-ya, come congratulate Valera,” Misha tried to prevent a conflict. “It’s his birthday today.”

Yura ran up to us. He didn’t want to listen to anything. He wanted the car, the car alone. He had to satisfy his wish and he didn’t give a hoot how he did it.

He could have yelled, stomped his feet, bitten or started a fight, ignoring the size of his opponent.

Only one person was capable of dampening his anger, though only for a short time.

Disobedience inevitably led to punishment – that was the rule established in the yard by my father. And he was the one who enforced it.

Yura was the one to whom my father would often give a flick on the forehead. He called that popping “champagne” for the sound it made, similar to that of popping the cork of a champagne bottle. He sometimes spanked him lightly on his bottom, which would send Yura flying across the yard. And when Father opted for ear-pulling, it was definitely far from pleasant.

All the children who visited Grandpa’s yard knew how strict “Uncle Amnun” was. His glance alone was sufficient to stop boys from dashing around the yard and make them tiptoe.

Naturally, they sometimes got carried away and started quarrels or fights. Father was always ready to ease the situation. He would beckon to the culprit, without a word, just motioning with his index finger, and dish out a dose of “medicine” to the guilty party.

While doing it, Father expected full cooperation from the punished one. At the sounds of “champagne,” they would count ten “flicks.” If a poor devil counted without enthusiasm, the whole thing was repeated. The memory of a punishment, long and bumpy, sat on one’s forehead.

When Yura saw that it was impossible to kick me out of the car, he grabbed hold of my hair but was immediately lifted into the air, where he remained hanging. It was my father who had lifted him by the scuff of his neck and pulled at his ear.

“And who did I beckon to?” he said quietly, drawing a breath with difficulty. “This is not yours. It wasn’t given to you. Go home immediately!”

My cousin walked away with a piercing cry.

The evening was spoiled for everyone. The parents started going home without saying a word. My car was left by the apricot tree.

“You don’t touch it either,” Father ordered as he went inside.

* * *Relatives and acquaintances who didn’t usually visit us inevitably showed up for my birthday. Many of them, who didn’t find it necessary to greet Mama when they saw her, greeted her on that day as if nothing wrong had happened. Then they would come up to me, hug me tenderly and congratulate me, “Look at him, he’s so grown up,” they would say.

And I stood looking at them with wide open eyes. I just stood there, stared at them and tried not to answer. I waited for them to leave and never visit us again.

Grandma Lisa also arrived to congratulate me.

“A, bvi. Chi to et?” Mama greeted her politely as was customary.

“The spondulosis has struck me again,” she answered, kneading her lower back with her fist.

Grandma always uttered this complaint through clenched teeth, hissing and winking, as if someone had inflicted a terrible pain on her and wouldn’t give her any relief. In other words, she was demonstrating how much she suffered.

Mama invited everybody to the table. After sitting down, Grandma immediately began to make herself the mistress of the repast, a repast that was somewhat strange because she acted as if Mama and us kids were not at the table. It was just her and her son Amnun, who was in her good graces that day.

“Amnun, what will you eat? Amnun, do you want some more? Amnun, what will you drink?” was heard at the table. Papa nodded sullenly. He was ill at ease.

The person who was always kind to Mama and us kids was Grandma Lisa’s brother Abram. He visited us often. He also came that day. I was glad to see him. Once Uncle Abram gave Yura and me a blue scooter. It was homemade, welded from rails. It was very heavy but safe. The point was not just his presents. I think children are finely attuned to other people’s attitudes toward them. They even sense their essence. And Uncle Abram wasn’t just kind and nice, he was the person all the relatives were proud of.

Stories about his “adventures” in combat were legendary. Perhaps they were made larger by added details as they were told and retold, but the main points were definitely true.

After he had been taken prisoner by the Germans near Lvov, he managed to pass himself off as an Uzbek, escaped a few times, was hidden by tenderhearted Ukrainian peasant women and then taken prisoner again. That’s how he knocked around for three years. When Soviet troops began their offensive, he was beaten almost to death after another escape but was liberated by one of the army units. Abram survived, recovered, returned to combat, reached Prague, was awarded many medals and orders, and returned home.

I don’t remember him wearing them to show off. Only once, while sitting on his lap, I managed to hold those round circles that were delightfully jingly and heavy.

After the horrible trials and tribulations of the war, Uncle Abram didn’t grow bitter. He didn’t break down but rather remained charming and bubbling with life, an amazingly kind man. The number of people he helped out – some with money, others with work – was great.

He could do that because he was very respected in town, even though he was just a taxi driver.

I heard from Mama that Uncle Abram always supported his sister Sonia, whose husband had been killed in combat. Sonia was a widow with three children, and they lived in poverty.

Every time someone spoke about Abram, Mama shrugged her shoulders, “I don’t understand who she takes after,” and she would look askance at Grandma Lisa’s house. Grandma Lisa was truly the complete opposite of her brother.

It began to grow dark. Jack whimpered softly in the yard – someone must be coming home. It was Grandpa returning from work.

“Here I am. Who is the birthday boy?” he said cheerfully setting his shoulder bag down.

He’d had a long day of work behind him, but Grandpa didn’t look tired. He had always been like that – encouraging, energetic. He didn’t like to use mass transit. Walking was his natural way of getting around. And he was quite fast, too. Not many people managed to keep up with him. “Hey, you!” he would reproach a walking companion who fell behind. And, clenching his fist, he would explain, “An empty sack cannot stand upright. You should eat well!”