Полная версия

The Power of Ritual

With over fifteen thousand communities worldwide, this phenomenon was something Angie and I had to pay attention to. And even though people new to CrossFit often came to lose weight or build muscle, what kept them coming back was the deeply engaged and committed community.

CrossFit was the most surprising and widespread example of people building community that echoed religious traditions, but it wasn’t the only one. Other fitness communities like Tough Mudder had similar qualities. At Tough Mudder, a community of people who get together to overcome a complex obstacle course – usually covered in mud – the leadership is wholly unafraid of religious comparisons. Founder Will Dean explained to Fast Company in 2017 that Tough Mudder races are ‘the pilgrimage, the big, annual festivals, like Christmas and Easter. But then we also have the gym, which becomes the local church, the community gathering hub. You have the media, which is a little like praying. Then there’s the apparel, which is a little like wearing your cross or your headscarf or any other form of religious apparel.’

Yet fitness communities aren’t the only way that people are finding and exploring questions of belonging. Groups that gather people around play and the creative arts were also spaces for building community. At Artisan’s Asylum, a maker space in Somerville, Massachusetts, a community has formed of artists, artisans, tinkerers, jewellery makers, robot creators, captains of mutant bicycles that look like spaceships, engineers, designers, and more. The creative spirit that runs through the space is embodied in the generosity of members showing one another how to use unfamiliar machines or materials. An active mailing list helps source difficult-to-find parts and helps new artisans get started. One woman shared that she wanted to make a complex butterfly Halloween costume for her young daughter involving lights that would flash on and off. Within hours, the material she needed had arrived on her doorstep and a highly skilled maker was ready to guide her through the process. At Thanksgiving, the whole community gathers for a giant potluck they call Makersgiving, with their creations adorning the long tables alongside homemade dishes. But Artisan’s Asylum has become more than a community. It is the place where people come to grow into the person they want to be. Learning a new skill like welding gives members the confidence to try something new like improv or singing. Becoming a mentor to someone new to a craft shapes how members see themselves in the world. And because the space is open twenty-four hours a day, and a number of members have insecure housing, the whole community has become passionate about advocating to city government about better public housing. The congregational parallels are not difficult to spot.

After a year and a half of interviews and participant observation, Angie and I were ready to share what we’d learned in our ‘How We Gather’ paper. We found that not only did secular spaces offer people connection in similar ways that religious institutions once did, but they also provided other things that filled a spiritual purpose. Communities that we studied offered people opportunities for personal and social transformation, offered a chance to be creative and clarify their purpose, and provided structures of accountability and community connection.

And because the leaders of these communities became trusted and respected, they were often approached by community members about life’s biggest questions and transitions. We heard of weddings and funerals being led by yoga instructors and art class teachers, of people being counselled through a diagnosis or breakup by leaders more expert in fitness than finer matters of the heart and spirit. One SoulCycle instructor remembered getting a text on a Sunday afternoon from one of her regular riders simply asking, ‘Should I divorce my husband?’ With no formal training or preparation to handle these momentous life transitions, community leaders did their best anyway. Communities rallied around members who were sick – bringing food, raising money for hospital visits, and driving them to appointments. More and more, even though they looked nothing like traditional congregations, we saw how old patterns of community were finding new expressions in a contemporary context.

What studying these modern communities taught me is this: we are building lives of meaning and connection outside of traditional religious spaces, but making it up as we go along can only take us so far. We need help to ground and enrich those practices. And if we are brave enough to look, it is in the ancient traditions where we find incredible insight and creativity that we can adapt for our modern world.

Why This Matters

Noticing these shifts in community behaviour isn’t just interesting. It’s important. In the midst of a crisis of isolation, where loneliness leads to deaths of despair, being truly connected isn’t a luxury. It’s a lifesaver.

Rates of social isolation are rocketing sky high. More and more of us are lonely and unable to connect with others in the way that we long to. A 2006 paper in the American Sociological Review documented how the average number of people that Americans say they can talk to about important things declined from 2.94 in 1985 to 2.08 in 2004. Essentially, we’ve each lost someone to care for us in the moments when we most need it – and that number includes family members and spouses as well as friends. Our social fabric is fraying.

Health officials now talk of social isolation as an epidemic. When Dr. Vivek Murthy moved through his confirmation process to become the nineteenth US Surgeon General in 2014, he was asked which health issues he particularly hoped to address. In an interview with Quartz, he explained that he ‘didn’t list loneliness in that priority list because it was not one at the time’. But while travelling around the country, he met numerous people who would tell him stories of their struggles with addiction and violence, with chronic illnesses like diabetes, and with mental illnesses like anxiety and depression. Whatever the issue, social isolation made it worse. ‘What was often unsaid were these stories of loneliness, which would take time to come out. They would not say, “Hello, I am John Q, I am lonely.” What they said was “I have been struggling with this illness, or my family is struggling with this problem,” and when I would dig a bit it would come out.’ Disconnection sours the sweet things in life and makes any hardship nearly unbearable. Indeed, suicide rates are at a thirty-year high.

The data are clear. In a landmark meta-analysis of over seventy studies, Dr Julianne Holt-Lunstad demonstrated that social isolation is more harmful to our health than smoking fifteen cigarettes a day or being obese. Holt-Lunstad concludes in her 2018 American Psychologist paper that ‘there are perhaps no other facets that can have such a large impact on both length and quality of life – from the cradle to the grave’ as social connection.

While our culture often lifts up the importance of self-care, we’re desperately in need of community care. Without it, the impact of social isolation shows up in numerous ways. It is harder to find work. We fall out of healthy habits. And in heat waves or superstorms, we’re more likely to be forgotten by neighbours and perish.

Perversely, when we feel far away from one another, our brains have evolved not to foster connection, but instead to strive for self-preservation. Vulnerability and empathy expert Dr Brené Brown explains in her book Braving the Wilderness, ‘When we feel isolated, disconnected, and lonely, we try to protect ourselves. In that mode, we want to connect, but our brain is attempting to override connection with self-protection. That means less empathy, more defensiveness, more numbing, and less sleeping. . . . Unchecked loneliness fuels continued loneliness by keeping us afraid to reach out.’ My husband and I call this entering the doom spiral, where one thing leads to another, and soon it feels impossible to get out.

Once in the doom spiral, our brains desperately try to counteract the loss of social connection but struggle to do this alone. In his landmark book In Over Our Heads, Harvard developmental psychologist Dr. Robert Kegan explains, ‘The mental burden of modern life may be nothing less than the extraordinary cultural demand that each person, in adulthood, creates internally an order of consciousness comparable to that which ordinarily would only be found at the level of a community’s collective intelligence.’ More simply put, we need to recreate an entire village network of support in our own brain. Alone. And this goes far beyond physical support and even mental health. ‘We feel unaccompanied at the level of our own souls,’ writes Kegan.

Yet despite the dire warnings that these statistics offer, there is hope. The solutions are age old and all around us. As much as for our joy as for our health, we can deepen our existing connections to the world around us and to one another. We can regrow those relationships that have withered away. We can be one another’s medicine.

I have learned that disconnection is about more than our physical and emotional wellbeing. Our spirits, too, suffer. Without rich relationships and a sense of connection to something bigger than ourselves, the occasions that could mean the most in our lives feel emptier. As we encounter major life moments – weddings, births, funerals – we often find ourselves at a loss for how to mark them without the rituals we once had with religion. Think of Cheryl Strayed’s story in her memoir, Wild, about how, without a religious upbringing, she didn’t know what to do when her mother died. What would happen at the funeral? Who could she go to for help during her grief? Generations before us turned to the church or the temple during these times: the priest or rabbi would lead the funeral ceremony, congregation members organised meal deliveries for the family, and everything was taken care of. All of us would know what to do. But today? Just like Strayed, we’re overwhelmed. Without clarity on what to do when we meet these milestones, we let them pass by, unable to live through them wholeheartedly.

More than that, the number of occasions we deem worthy of ritual are embarrassingly small. It strikes me that as the cost and stress of weddings has gone up, the number of other rituals and celebrations has gone down. If we no longer celebrate spring or harvest time, the new moon or a young person’s coming-of-age, is it any wonder that our human hunger for meaning gets amped up on the one day in our lives when we’re actively engaged with designing a ceremonial experience?

What I propose is this: by composting old rituals to meet our real-world needs, we can regrow deeper relationships and speak to our hunger for meaning and depth.

But why are we in this mess? We need to understand the era-defining patterns in religious decline that we’re in, and what that decline means for each of our lives.

Rise of the ‘Nones’

Much has been written about the decline of religion and the rise of the so-called ‘nones’ (people who tick ‘None of the above’ when asked about their religious identity). Whereas nearly a century ago, Americans could assume that just about everyone around them fit into a religious box – Catholic, Presbyterian, Reform Jewish, African Methodist Episcopal, Quaker – today, many of us straddle multiple identities or have none at all. Perhaps you grew up with a Hindu father and a Jewish mother, celebrated both Passover and Diwali, and now find yourself practising a bit of both. Or your former-Methodist parents took you to an Episcopal Sunday school for a few years before church slowly drifted into the background of family life. Or perhaps, like me, you weren’t raised with anything in particular, but celebrated popular holidays and had a mix of family rituals and traditions. Wherever you fall on this spectrum, you are part of the shifting sands of religious identity and practice. The percentage of Americans who describe themselves as atheist, agnostic, or ‘nothing in particular’ has grown to 26 per cent, and 2019 General Social Survey data suggests that nones are now as numerous as evangelicals and Catholics in the United States.

Unsurprisingly, the trend is most pronounced for young people. Among millennials (those born between 1980 and 1995), the number stands at 40 per cent, according to a Pew Research Center poll published in 2019. Research data also suggests that each new generation is less religious than the last. A Barna Group poll in 2018 revealed that 13 per cent of Gen Zers consider themselves atheists, more than double the 6 per cent of American adults overall. But the trend toward disaffiliation holds true across every age cohort. In 2014, nearly one in five boomers were nones (17 per cent), and nearly one in four Gen Xers fit the same bill (23 per cent). All this results in massive changes in our religious infrastructure. For instance, Mark Chaves, a sociologist at Duke University, has estimated that over three-and-a-half thousand churches close their doors every year.

America is not alone in these trends, of course. In Europe it’s an even starker picture. A 2017 survey by the British National Centre for Social Research revealed that 71 per cent of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds consider themselves as nonreligious, while UK church attendance has declined from nearly 12 per cent to 5 per cent between 1980 and 2015. This has had huge implications on the Church of England. In the 2018 British Social Attitudes survey, only 1per cent of British 18 to 24-year-olds identified as CofE, and even among the over-75s, the most religious age group, only a third described themselves as Anglican. A similar trend has emerged in Australia, where nearly 40 per cent of Australians did not state a religious affiliation in the 2016 census, and attendance in church is down also.

Again, this isn’t to say that we are becoming less spiritual per se. But the data does tell us that how we engage our spirituality is changing.

It may be helpful to think of the human longing that leads to religious culture as akin to music and the music industry, which has struggled mightily over the last twenty years, with CD sales in free fall for much of the 2000s and 2010s. But our love for music itself endures. Decades after the technology-induced crisis, industry executives have figured out a new business model – combining streaming subscriptions with vinyl sales, which are at a fourteen-year high. The same thing is happening in our spiritual lives: a mix of fast-paced innovation and rich tradition. Attendance at congregations is down, but our hunger for community and meaning remains. Formal affiliation is declining, but millions are downloading meditation apps and attending weekend retreats. Moreover, they find spiritual lessons and joys in completely ‘nonreligious’ places like yoga classes, Cleo Wade and Rupi Kaur poetry, and accompaniment groups like Alcoholics Anonymous and the Dinner Party (a community-based grief support group for twenty- and thirty-somethings). Stadium concerts and karaoke replace congregational singing, and podcasts and tarot decks replace sermons or wisdom teachings.

In her book Choosing Our Religion, Elizabeth Drescher explains that we nones see our spiritual lives as organic and emerging, responding to the people around us rather than structured into dogmatic categories of belief and identity. Said otherwise, we’re less likely to affiliate with an institution than we are to affiliate with another individual. We see religious institutions as being driven by hypocrisy and greed, judgmentalism and sexual abuse, anti-scientific ignorance and homophobia. People also leave religious communities behind because worship experiences are simply boring or formulaic. Most interesting to me is that we are especially wary of a religious identity that threatens to ‘overwrite [our] self-identity in ways that seem to compromise personal integrity and authenticity,’ as Drescher writes. All this makes us nervous to even acknowledge that we might have a spiritual life. Tellingly, over half of Drescher’s hundred plus interviewees used the phrase ‘or whatever’ whenever they talked about something spiritual in their own life!

So let me say this clearly. However you express your spiritual life, it is legitimate. If you touch the sacred on the basketball court or on the beach, in cooking or crafting, in snuggling with your dog or singing in a crowd of thousands, during Yom Kippur services or at an altar call, while you read these pages you never need to say ‘or whatever’, okay? You can think of this book as giving you your dose of spiritual confidence and social permission.

Unbundling Traditions and Remixing Them

Like nearly everything else in contemporary culture, how we understand religion is shaped by the technological changes driving our lives, especially the rise of the internet. Institutions have lost our trust, particularly those that claim expertise and authority. But as Joi Ito, former director of the MIT Media Lab, explains in his book Whiplash coauthored with Jeff Howe, the emergent systems aren’t replacing authority. Instead, what’s changing is the basic attitude toward information. ‘The Internet has played a key role in this, providing a way for the masses not only to be heard, but to engage in the kind of discussion, deliberation, and coordination that just recently were the province of professional politics.’**

Let’s unpack that. The internet era has opened us to the possibility of curating and creating our own tailored practices and to looking to our peers for guidance as much as any teacher or authority figure. There are two key concepts here – unbundling and remixing.

Unbundling is the process of separating elements of value from a single collection of offerings. Think of a local newspaper. Whereas fifty years ago it provided classifieds, personal ads, letters to the editor, a puzzle for your commute, and of course the actual news, today its competitors have surpassed it in each of these, making the daily paper all but obsolete. Craigslist, Tinder, Facebook, HQ Trivia, and cable news offer more personalisation, deeper engagement, and perfect immediacy. The newspaper has been unbundled, and end users mix together their own preferred set of services. Printed news is having to find a new value that it alone offers.

The same is true for our spiritual lives. Fifty years ago, most people in the United States relied on a single religious community to offer connection, conduct spiritual practices, ritualise life moments, foster healing, connect to lineage, inspire morality, house transcendent experience, mark holidays, support family, serve the needy, work for justice, and – through art, song, text, and speech – tell and retell a common story to bind them together. Further back, religious institutions provided health care and education too. Today, all of these offerings have become unbundled. Some health care and education is provided by the state, while for those who can afford it, various private corporations provide the rest. Communal seasonal celebrations have shifted to sporting events like the Super Bowl, national celebrations like the Fourth of July and Thanksgiving, with only a sprinkling of religious highlights remaining, most notably Christmas. As for life transition rituals? We mostly make those up with our friends as we go along, if we have enough time and energy for it.

We might introspect by using a meditation app like Headspace or Insight Timer, find ecstatic moments of connection at a Beyoncé concert, and go hiking to find calm and beauty. We set our intentions at spin classes and make a note of thanks in our gratitude journal. We express our connection to ancestors through the dishes we cook, we feel part of something bigger than us at a protest or a Pride parade. The core needs of introspection, ecstatic experience, beauty, feeling like we’re part of something bigger – these have existed for millennia. But how we create these experiences varies over time. Where religious institutions have been mistaken, as innovation expert Clayton Christensen might put it, is that they’ve fallen in love with a specific solution, rather than forever evolving to meet the need.

Meanwhile, there’s a growing number of mixed-religion households. Before the 1960s only 20 per cent of married couples were in interfaith unions, while in this century’s first decade 45 per cent were, according to journalist Naomi Schaefer Riley. Harvard Divinity School dean David Hempton labels this phenomenon ‘braiding’. Jewish teacher Reb Zalman calls it ‘hyphenating’. Marketing guru Bob Moesta refers to it as ‘remixing’. Whatever we call it, and however much religious institutions resist it, it is happening. And not just in the United States.

Anthropologist Satsuki Kawano describes how Japanese people have been Shintoists and Buddhists at the same time for decades, practising elements of both traditions without seeing themselves as necessarily members of two separate religions. In her book Ritual Practice in Modern Japan, she explains that the Japanese state has tried to separate the two religions but that, despite its efforts, the two remain deeply entwined. There have been tensions and conflicts through the decades, but no religious wars or effort to eliminate one another. Indeed, Shinto and Buddhist traditions have interacted, and whole theologies integrating the two have come to flourish. ‘As a result,’ she writes, ‘mutual influence [has] led to a complex orchestration and integration of native and indigenised foreign practices without completely eliminating distinctions between the two traditions.’ One might go to a Shinto shrine for weddings and children’s celebrations but have one’s funeral in a Buddhist temple, for example.

But as we benefit from unbundling and remixing traditions that allow us ever more personalisation, we find that we share less and less with one another. We’re left isolated and longing for connection.

Four Levels of Connection

Like me, you might have been raised without a religious background. Or perhaps you were born into an identity that doesn’t quite fit. You might be atheist, agnostic, at the edge of your tradition(s), spiritual-but-not-religious, unsatisfied in your spiritual home, or simply unsure. Whatever language you use to describe yourself, you’ve been patching together your spiritual life and are longing for something authentic, something more meaningful, something deeper.

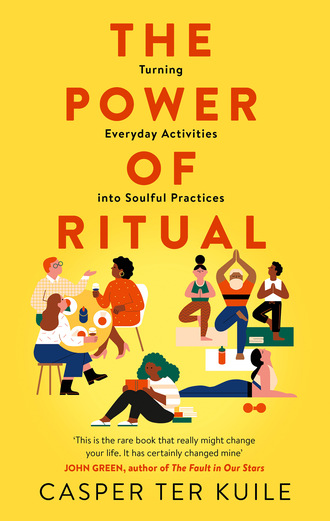

The purpose of this book is to show you how you can transform your daily habits into practices that create a sacred foundation for your life. I’ll share some ancient tools reimagined for today’s culture, and I’ll tell some stories about others who are showing us a way forward.

Deep connection isn’t just about relationships with other people. It’s about feeling the fullness of being alive. It’s about being enveloped in multiple layers of belonging within, between, and around us. This book is an invitation to deepen your rituals of connection across four levels:

Connecting with yourself

Connecting with the people around you

Connecting with the natural world

Connecting with the transcendent.***

Each layer of connection strengthens the other, so that when we feel deeply connected across those four levels, it’s as if our days are held within a rich latticework of meaning. We’re able to be kinder, more forgiving. We heal. We grow.

And each of these layers is rooted in insights from many of the world’s wisdom traditions. For thousands of years those traditions have kept communities together, helped people grieve loss and celebrate joy. The great myths of the world helped us make moral sense out of chaos and catastrophe. Even if we’re a little nervous to engage the traditions, they have much to teach us.

Some things have changed, of course, since these ancient traditions were established. No longer do we need myths to explain how the sun rises and sets, where floods come from, and what lies underground. Instead we have new questions. How can we truly find rest in a stressed-out 24/7 world? How can we remember our ‘enough-ness’ in an economy that always pushes for more? How do we cultivate our courage to stand against injustice?

In Chapter 1 I’ll explore two everyday practices that help us connect to our authentic self: sacred reading and sabbath. Chapter 2 proposes eating and exercising together as two sacred tools to help us connect deeply with others. Chapter 3 focuses on reimagining pilgrimage and the liturgical calendar to connect us more intimately with the natural world, and Chapter 4 explores what connecting to the divine might look like by reframing prayer and participating in a regular small group of support and accountability. Finally, Chapter 5 is a reminder that we are all inherently born into belonging. The practices here are simply the tools to help us remember.