“Father,” he said in Learish.

Mora’s lips parted, and the sour battlefield air rushed down her throat as pain slammed into her again. It throbbed with her pulse. She would fall to her knees if she did not sit soon, and curse her spirit to the darkest saint’s grave if she knelt before this particular man.

Glennadoer’s son was Rowan Lear, prince and heir to the island crown.

“I’ve caught Banna Mora for your hostage,” Glennadoer said, voice full of humor.

Rowan dismounted and strode toward them, eyes on Mora. She blinked and struggled to maintain focus. He was a hand taller than her, but stopped far enough back she could hold his tiger-iron gaze.

“Banna Mora,” he said, voice surprisingly soft.

“Rowan,” she replied, more harshly. She’d not seen him since they both were fifteen, nearly a decade ago. The prince of Innis Lear had traveled to Lionis where King Rovassos had named Mora his heir in an elaborate ceremony and week-long celebration. He’d been weedier then, not grown into his dramatic features, and coolly unfocused, as if seeing a world beyond Aremoria. She’d been distracted by the weight of the Heir’s Score at her hip.

It took all of Mora’s willpower, in her concussed, battle-weary state, not to put her hand over her chest plate to feel the ring concealed against her breastbone.

“Take her to the cliff and put her in my tent,” Rowan said to someone behind her. “Clean and care for her, and ready her as best you can to leave.”

Mora curled her mouth into a sneer, but Rowan bowed to her, despite the fact that Mora no longer met him in rank.

She said nothing for the roar of blood in her ears, the pounding pain, and her trembling knees. When the healer touched her shoulder, she melted into the stretcher. Mora attempted to ignore the voices in her head telling her to get up, to argue, to keep fighting. There was information she needed, at the very least: How many of her soldiers were dead, how many dying, who captured alongside her? What did Glennadoer intend to do with the March? Her March, now subdued? Celedrix ruled over a messy Aremoria, nearly a year since her rebellion, but she was not so weak that she could not throw Innis Lear off her lands. In fact, an enemy to defeat might bring some of her bitching nobles together.

Banna Mora drifted in a tumbling river of aches and nausea as the stretcher carried her nearly a mile to the bluffs overlooking the sea. Even the thought of opening her eyes roiled her stomach. The March stretched a hundred miles in the north of Aremoria, along the western coast north to Burgun, pushing east toward Perseria: wet lands of river deltas and fertile fields, with the crumbling ruins of a cliff-side temple carved into rock and built up into natural caves. This was said to be the home of that ancient wizard who furiously broke the land apart and created Innis Lear. It had been her father’s, and his before that, and then Mora’s since her parents drowned crossing back to the island. Now it belonged to Owyn Glennadoer. Soon Vindomata of Mercia would retake it, or maybe Hotspur. Mora groggily hoped it would be Hotspur.

The healer and two soldiers helped her off the stretcher when they passed into the thick shade of a tall canvas tent. She did not open her eyes, even as the shackles were removed and she was stripped bare.

When a soldier touched the chain at her neck, she glared at him. Even the dim light stabbed at her brain. “Leave it,” she said, curling her fingers around the thin leather pouch hiding the Blood and the Sea.

They obeyed. The tent was stark, fit for a campaign and lacking the ostentation of Aremore royal tents. A bath was filled and Mora gave over to their ministrations. She was gently bathed and her tender head washed. She was given simple bread and a broth along with very watered wine. Time lost coherence as Mora sank in and out of sleep. But it was sleep, not unconsciousness. The healer spread a salve on her open wounds, binding all, and murmured that the swelling egg at the back of her skull was not too large nor hard.

The fur bedding, intended for the prince of Innis Lear, was warm and comfortable.

Candles were lit, and then she was abandoned to her own devices, unshackled. Mora was no threat in this state. Her body hurt everywhere and, though her stomach had settled, if she moved too quickly knives of pain slashed her brain and she grew faint.

She held the wool jacket they’d given her tightly closed over the loose tunic and long shift they’d dressed her in. Leggings waited on a stool, but Mora didn’t relish the thought of getting back out of them to relieve herself. As it was, she suspected this clothing belonged to Rowan Lear, too. Plain linen for the shift, but the tunic was embroidered with lines of blue hash-marks she knew to be the language of trees.

Mora drank the last of the watered wine from the large mug they’d given her and lay back. She slept immediately, only to be woken by a soft hand on her bare ankle. “Banna Mora.”

Opening her eyes, she winced at the headache—duller now, but there—and the strange fire aura the candles cast in her vision.

The prince crouched beside her in a sleeveless blue tunic and leggings, his glorious white-gold hair loose and falling damply down his chest. Tattoos marked his white biceps: more hash-marks, constellations, and a cuff depicting the nine phases of the moon.

“Rowan,” she croaked.

He held out a mug. “Drink.”

Getting her arms under her to push up and sit took three tries. He did not offer aid, for which she was both grateful and resented. Her arms shook, but she succeeded.

Behind the prince, the tent entrance had been pinned open, and darkness pushed close. “What time?”

“Several hours before dawn. My ship leaves shortly.”

“I need to piss.”

“In a moment.” Rowan offered the mug again.

Scowling, Mora took it and drank. Her need to relieve her bladder was not urgent. This wine was just as watered as before, weak and near tasteless. She sipped slowly, knowing better than to guzzle in her state.

“You aren’t my hostage, Banna Mora,” Rowan said, startling her.

Mora narrowed her eyes and set the mug onto the floor rather hard. “Fuck you.”

A smile pulled his mouth unevenly. “I remember when we were both heirs to magnificent thrones, cousin, and I would not renew our acquaintance with such a power imbalance as hostage and sovereign.”

She scoffed. “Why did you invade Aremoria if not for hostages?”

“My father was bored and wanted to flex his muscles, and the stars and the wind required that I join him.”

“Oh, wormshit, Rowan.”

He said nothing in response, but regarded her steadily. The candle flame caught at the gold in his eyes and turned it to matching fire. Mora remembered Glennadoer had said, My son obscured them from your scouts.

She glanced down. There was magic on Innis Lear. She knew it, remembered it, remembered her young brother who had gossiped with butterflies and trees even when he’d been barely old enough to walk. “You won’t be able to keep the March,” Mora said to the rippling surface of the watered wine.

“I don’t need to keep it.” I have you, his tone added.

Pressing her mouth shut, Mora refused to snap back what a waste of blood this had been if he’d only attacked for some prophecy. Except—he’d been the one to cast the prophecy for Celedrix, the one announced at the tourney. Had he known Mora was considered part of it? What game did Rowan Lear play?

“I want you to go home with me,” he said.

“You have me under your power, no matter what you say about equal titles.”

“No.” He touched her chin, tipping her head up. “Mora, if you will not go with me of your own accord, I’ll leave you here in this tent, with six of your soldiers we’ve captured. Once we’ve gone, you can return to your queen and live whatever life she allows you, whatever life you’ve had since Rovassos died.”

Mora forced her breath shallow again, and slow, and forced herself, too, not to tug her chin free of his touch. Her body tightened into aches as she sat so still. The bed below her tilted and turned as if she were drunk. Her skull throbbed; her left side was near numb with pain. But she would not shift for comfort. “Why would I go with you, only to be subject to the same denigration I face here in Aremoria?”

“Innis Lear would love you, and welcome your presence. Does Aremoria offer the same?”

“Of course,” Mora lied.

Rowan released her, his hand falling to his knee. “You belong on Innis Lear, if for nothing else than to hear the wind again, to drink the rootwater. To visit your brother and great-grandmother before she dies. To meet your cousins again, none of whom have seen you since you were a child. Your blood is in our island.”

“My blood is in my veins, and I feel its heat whatever land I walk,” she replied viciously.

That brought a smile again to Rowan’s mouth. “We leave shortly. If you will go with me, you need to choose in the next few moments. I’ll go, and send in a retainer to hear your answer. I hope you pull on boots and come. I promise to show you everything Innis Lear holds, of strength and passion and magic.”

With that, Rowan Lear stood. His hair brushed his tunic with a whisper, and he was gone.

Grimacing at the pain, Mora fell back, giving in to a moment of abject suffering. Tears leaked from her eyes and she moaned softly.

It twisted her heart to think of leaving Aremoria: it was hers. Her country, her destiny, hers. Or it had been. She slapped her hand against her breast; the lump of leather hiding the Blood and the Sea filled her palm.

Would Celeda even ransom her if Mora were taken hostage by Glennadoer and his royal son? Or just leave Mora to languish on Innis Lear, pretending the loss was a tragedy but eager for the excuse to be rid of a troublesome potential challenger to the throne?

She knew the answer.

Anger, hurt, and an old yearning she could barely name choked Banna Mora; when the retainer ducked inside for her intentions, the lady of the March demanded her boots and the return of her armor. She would not set foot on Innis Lear a half-dressed invalid.

No—only as a lost heir coming home.

PRINCE HAL

Lionis, spring

HAL BURST INTO her mother’s study. It was a long mirrored room with white and deep gray molding, the narrow vaulted ceiling painted with a tangle of grapevines as if the room were an arboretum. Two tall cages guarded the door, each with seven finches hopping, chirping, fluttering their wings. At the far end, Celeda’s desk sat between unlit braziers and was surrounded by a cluster of men. The queen watched Hal, quill paused in hand, face blank.

Walking the length of the room was a quick ordeal under the eyes of those advisors and her mother’s disapproval.

“Mother,” Hal said. She’d obviously come from the bath, in a hastily donned gown laced unevenly and her thickly braided hair dripping down the back of her neck. There’d not been time to wait when Nova told her the news.

“Leave us,” Celedrix said. She signed whatever she’d been preparing to sign and slid it toward her steward. The rest bowed and departed, but for Abovax, a grizzled soldier in Aremore orange Hal had known since she was a child, who now commanded the palace garrison. He watched with a skeptical look, leaning against the wall behind the queen’s left shoulder.

Hal took a deep breath, tried to be calm, but couldn’t. She complained, “You should have sent for me!”

“Why?”

The cool voice infuriated her, but Hal pressed her mouth shut, seething a moment. Celeda’s lifted eyebrows declared her limited patience, and she folded her hands together atop the shiny lacquer of her fancy desk. The Blood and the Sea was an understated reminder of her power, and Celeda mirrored that restraint in her presentation: she wore a plain dark red robe with a black mantle circling her long neck and spread out over her shoulders, back, and chest. Her hair—as dark as Hal’s, but lately showing some gray in delicate threads—was bound up in a plain but elegant roll. Garnets pinched her earlobes, and a thin line of black had been applied to her lashes.

Hal groaned in frustration. “The March is taken by Innis Lear! Banna Mora is a hostage!”

“Ah, it is good to know what sort of crisis my heir will rouse herself for.”

Such delicate condemnation stole Hal’s breath away.

Celeda gestured to one of the thin chairs tucked against the wall of mirrors. “Have you eaten today?”

“Mother!” Hal stormed close enough to slap her hands on the desk. Abovax frowned at her, but Hal leaned toward her mother. “What are we going to do?”

“Hotspur leaves as soon as her company is ready, to retake the March.”

“I want to go with her.”

“No.”

“I am good at soldiering, Mother, let me do something I’m good at!”

“Your presence in the field is not necessary—I don’t believe Innis Lear intends to retain what they’ve taken, and soldiers under the Wolf of Aremoria will be enough. Vindomata will come from the east with men from Mercia for backup.”

Hal stared, still leaning over the desk. “They don’t intend to keep it, because there’s been no message from Solas Lear? You think they’d have declared war some other way?”

“There has been no war between Lear and Aremoria in generations, and we have been the strongest of allies since Morimaros’s reign. They would not break it now—this is Glennadoer flexing his muscles, or he wanted Mora for some purpose of his own.”

“What purpose?”

Again, Celeda gestured toward a chair. Hal clenched her teeth and went to it, grabbing it by the back. She swung it around to sit backward, recalled she wore a dress, righted the chair, and sat hard. “What purpose?” she asked again.

“Work it out for me.” Celeda’s eyes, a lighter brown than her daughter’s, held evenly upon Hal.

Fine, Hal could break this situation into its parts, if that would prove something to her mother. She said, “It … depends. If Glennadoer acted on his own he might want Mora for alliance, or he might be doing it against Solas, not against us. But he’s married to her sister—his son is the heir to their crown. It doesn’t make sense he’s causing her problems.”

“A father might wish his son, who is heir to a crown, to marry well.”

Hal’s eyes bulged. “You’ve got to be joking. But then why wouldn’t they offer for her? With a messenger or a letter? Besides, it’s not a good match. She’s already Learish, it would be like marrying anyone from his island. She’s not a prince anymore, and is … in an awkward position with the Aremore throne. If Rowan Lear and Banna Mora married it would be condemning of … well, of you.”

“Especially when I have more than one eligible daughter of my own,” Celeda said in a way that should have been amused but certainly was not.

“You don’t think it’s for marriage then?”

Celeda shrugged one shoulder. “If it is, I think it has little to do with alliance or lack thereof with Aremoria. Innis Lear is the sort of place more concerned with their own power and bloodlines than those outside its borders.”

“And Mora’s bloodline is …” Hal crossed her arms around her stomach.

“Better than ours,” her mother said, and this time she was darkly amused. “Thanks to the recklessness of Morimaros the Great.”

The prince, wise for once, chose not to disagree. Hal licked her lips, thinking. “Then maybe this is a game, or a test? A reminder of their strength after the rebellion. Their challenge to a new queen?”

Celeda smiled grimly. “That, my daughter, is exactly the sort of behavior to expect from a queen of Innis Lear. Especially after that performance at my tournament last summer.”

“How will you answer then? If they’ve taken Mora hostage, how will you respond? Pay ransom, or send a force to steal her back?”

“It will be some days before a ransom could be begged.”

“But you already know what you will do.”

“How I act depends on many things, Calepia. How swiftly Hotspur retakes the March. The phrasing of the ransom request. If they even make such a request. It is possible Mora is less a hostage and more a willing Errigal lady returning to her family.”

“You have to sue for her return, Mother—show her you want her back. She’ll come home.”

Celeda remained silent.

“Don’t you want her home?” Hal paused to regain her ground. “Banna Mora chose us, this place, over Lear. She gave everything of herself to Aremoria.”

“And we took it away from her.”

“She’s not your enemy,” Hal said, absolutely certain.

“She is perceived to be so, by many. And constantly rumors rise and fall about her loyalties, about what she would do if given a chance to retake the throne. Perhaps it is better for her to be on Innis Lear.”

“No!” Hal stood. “It makes you look weak to fear her like that.”

“It made me look weak to allow her to attend my court, to keep the March.”

“That was the right thing to do. She is not Rovassos, and you are not Rovassos, swayed by temper! Mora is a good woman, a strong knight, and she was a brilliant heir. You look stronger to have her as an ally.”

Again, Celeda remained quiet, unblinking.

Hal glanced almost desperately toward Abovax. The commander grunted. He said, “When Banna Mora is here, you reflect poorly, Prince.”

“I …” Hal gaped at her mother. She could think of no response.

“The true heart of the matter, daughter, is that I do not know if Banna Mora is my ally.”

“Treating her like no friend at all will certainly make her an enemy. You must show her loyalty if you would have hers.”

Celeda shook her head. “You are naive. Queens do not perform loyalty, it is owed to them. And either a queen has it, or she does not. Do you recall Rovassos performing friendship, loyalty? With his charm and favors? Those things came into conflict frequently and he had no core integrity. He did not know how to trust anyone. That is what lost him his head. I do know how to trust, but I am careful with that trust.”

“I trust her,” Hal said softly. She went around the desk and to her knees beside her surprised mother. The queen turned slightly in her chair, hands falling to her lap. Hal said, “I trust Banna Mora, Mother. Your Majesty. Do you … trust me?”

Celeda’s lips trembled slightly, her hesitation telling Hal the answer. “I want to,” Celeda replied, just as softly. “I love you.”

Hal lowered from her knees to slump back on her heels, head bowed.

“Why are you giving in to the characterization of the lion of the Innis Lear prophecy?” Celeda asked.

Her head snapped up. “What?”

Celeda did not move; her eyes looked through Hal, toward some future or chance invisible to her daughter. “Breaking, daughter. You have been dubbed the lion, and instead of it making you bright and brave, you act as though you are breaking, just like in the prophecy. Giving credence to the entire thing.”

“You don’t … it’s a … you don’t believe in destiny or that we need the approval of spirits and stars.”

“Oh, but we need the approval of Aremoria, Calepia Bolinbroke. Aremoria is its people, and sometimes its people consider spirits and superstition! How do you think we shed old religions? How have the kings of Aremoria made themselves into the ultimate authority?”

“Stories,” Hal whispered.

“Extremely good stories. I’d have said legends, for when you say stories it sounds like a children’s pastime, and this is no game.”

“I know that!” the prince climbed to her feet, awkward in her anger as she looked down at her royal mother.

Do you? the queen’s eyes wondered.

Hal said, licking her lips, “I know it matters, Mother—less the prophecy itself and more what people believe it means.”

“It means what you, or what I, or what the Aremore people say it means!” Celedrix rarely lost her temper, and the snap was quiet, but plucked like a tense thread of anger. “And you have said nothing about this prophecy! You neither embraced it, nor denied it, nor made it a great joke! You should have found a way to make it your tool rather than ignore it, and if you cannot see that, you have learned nothing this year.”

Hal swallowed. “I thought confronting it would give it more power.”

“Perhaps, but it would be power under your control. Not under Banna Mora’s, or any ally she makes on Innis Lear.”

“Mora won’t use it against us. She won’t act against us.”

The queen sighed. “Everyone changes. Over time, and through trauma. You must see how allowing this prophecy to ring throughout Aremoria uncontrolled is a terrible plan. Find a way to use it, Calepia. If you already had, perhaps Mora would still be at our sides. Why can’t you be better at this?”

Her mother’s disappointment was like tiny, icy knives. “I didn’t have a mother to teach me to be better,” Hal said. “I had Banna Mora, and Lady Ianta. I am the one who was here.”

“I know.”

This time, Celeda’s voice was tender. There was sorrow in the queen’s eyes, and she held out her hand. Hal took it. Celeda’s skin was cool and dry, paler than Hal’s, the curve of her neck elegant, and Hal felt ungainly, calloused and strange.

Hal knelt again, and touched her cheek to her mother’s knuckles.

“Learn from me, Hal,” Celeda said. The nickname was a breath of relief, though still strange on her mother’s tongue. “I know you can do this. You are my daughter, and you have survived much. You can rise above your past, and your struggles. This incursion from Innis Lear is a call to any of our enemies who would take advantage of a weakened Aremoria. And we are weakened, Hal, because of my rebellion. Because I took a crown instead of inheriting it. Though I am a better king than Rovassos, my line is not secure—and won’t be until you are married and bear a child or two—”

“Saints, Mother.” Hal made fists against her lap.

“Echarmet cannot be here until next year because he serves in the Mother of All Mothers’ army, as their princes are expected to serve. But he will help you, and I know him well. You will be friends, if you can be open to such. Make it to your marriage, Hal, and all will be well. It will not matter what Banna Mora does; we will have the strength of the Third Kingdom behind Aremoria, and the promise of a stable succession.”

If she was trying to comfort Hal, her mother’s words played to the opposite effect. How could a country be stable if its leader was heartbroken? And surely she would be so if forced to give herself to this prince. Hal already belonged to Hotspur.

She thought of the prophecy, and wondered if she could use it, but not exactly as her mother said.

“If …” Hal did not move from her supplication. “If I can make myself into a better version of the lion prince, and prove the Wolf of Aremoria is mine—that she will choose the end for me—would that be enough?”

Celeda turned her hand to cup Hal’s cheek. “Perhaps.”

Hal shivered, a seed of doubt in herself planting deep, even as she thought this was a chance to carve space for herself and Hotspur, just as Ianta had tried to do, in the halls of power. “Thank you.”

“You may go,” the queen said gently.

THE OUTER YARD of the palace garrison teemed with soldiers, attendants, and horses as Hotspur readied her troops. Hal moved through easily, mostly ignored since she wore none of her armor nor signals of status. She’d straightened her gown, at least, before coming out here, but hadn’t allowed herself time to get her sword or have anything fancy woven into her braid. She had her Bolinbroke ring, and the ring inherited from her father; nothing else.

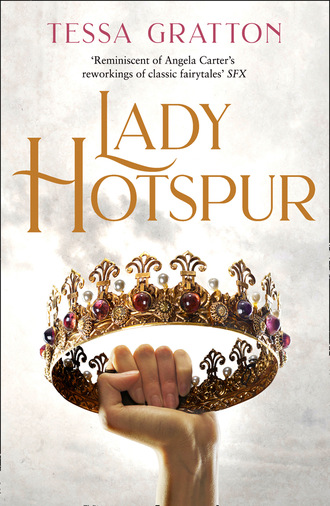

She spied Hotspur standing with Sennos atop a wagon already half loaded with canvas and pegs and rope for setting camp. Hal made her way nearer, stopping ten paces out to yell, “Lady Hotspur!” in a clear voice that rang out over the clatter and harried conversation.