Полная версия

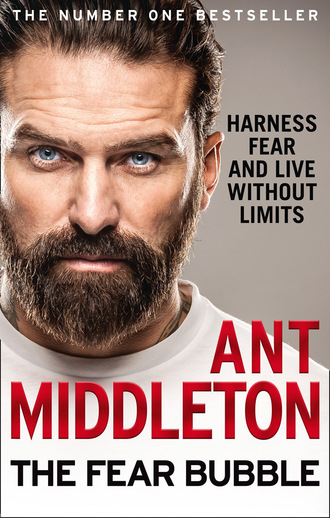

The Fear Bubble

More than anything else, I believe that my ability to harness fear and use it to my advantage is the secret of my success. There’s no way I would have come out of Afghanistan, or any other theatre of war, in a healthy psychological state if I hadn’t learned how to do this. And more than that, there’s no way I’d have been a success in my personal or professional life if I hadn’t developed the ability to grab hold of the incredible power of human fear and let it take me where I wanted to go. I’ve now got to a place where I rely on fear. When it goes missing from my life I find myself becoming anxious and dissatisfied. Without fear, there’s no challenge. Without challenge, there’s no growth. Without growth, there’s no life.

INTO THE BUBBLE

This method for harnessing fear has changed my life in ways that are almost unimaginable. It’s transformed me from the naïve, angry and dangerous young man I once was to the person I am today. The good news is that anyone can learn it. I call it the ‘the fear bubble’.

Back when I was in the military, there were many times in the breaks between tours when I caught myself thinking that I didn’t want to return. The fear you experience on the battlefield is unbelievably intense. There are many different levels of fear, but ‘life or death’ is surely the worst of them all. Most people never experience the feeling that when they step around the next corner there’s a decent chance they’ll take a bullet in the skull. I had to deal with that time and time again.

Many amazingly brave and tough operators didn’t find a way of processing that level of fear and horror. I’ve seen the hardest and best soldiers brought to their knees, reduced to crumbling, quivering wrecks, in floods of tears. That’s what fear can do to you if you fail to harness it and let it trample you. Today, many of these men are suffering from serious, debilitating mental disorders from which they might never recover. Their marriages have fallen to pieces, they can’t sustain regular employment, and they’re utterly lost in drugs and alcohol. Some are homeless, some enmeshed in a life of street crime. They’ve been destroyed by fear.

Although I was determined not to become one of these men when I served with the military, I could feel the effects of fear creeping up on me. When I was in the Special Forces, I’d be dropped off in a war zone in some grim and dusty back-end of the planet, and then for six interminable months it would feel as if I were utterly trapped in this enormous bubble of constant, crushing dread. As soon as I left the theatre of operations and my plane touched down in the UK, the bubble would suddenly burst and life would be great again. But when I began counting down the days until the start of the next tour, I started to experience that gut-wrenching feeling all over again. I didn’t want to go back.

For a while I couldn’t work it out. What was wrong with me? What was that heavy, greasy sensation in the pit of my stomach? I loved my job. So why was I feeling that I didn’t want to go back? I had to be brutally honest with myself. The truth was, I was shit scared. Fear had got a grip of me, just like it had got a grip of thousands of brave and capable men before me.

I didn’t know what to do. How could I ever solve the problem of experiencing intense fear on the battlefield? Of course you’re going to be scared when the air is filled with bullets and the ground is filled with IEDs (improvised explosive devices). Surely this was an impossible task? It then occurred to me that if I couldn’t get rid of fear completely, perhaps I could break it down into smaller packets so that it was a little less all-consuming and relentless. So that’s what I did. After giving it some thought, I realised I needed to adopt a coldly rational view of why I was feeling scared and, even more importantly, when I was feeling scared. Why, for example, was I experiencing such dread two weeks before my deployment, when I was still in the safety and joyfulness of my family home? There was nothing to be scared of there. Nothing whatsoever.

And while I was at it, what was the point of being scared when I landed in whatever unnamed conflict zone to which I happened to have been assigned? We were usually stationed in a secure area inside some form of military base. If you actually thought about it, a military base was one of the safest places on the planet, teeming with highly trained men and women, and guarded with the latest military equipment. There was not much, realistically, to be scared about there. Statistically, you were probably more likely to be walking around with an undiagnosed tumour in your body than you were to be killed by the enemy in a place like that, and nobody on the base was running around all day fretting about whether or not they had cancer.

And what about when I was on an actual operation? When I was dropped off behind enemy lines, I didn’t need to be in that bubble of fear. No bullets would be flying. We’d land in a safe space and be entirely incognito. The lads would be with me. When I was approaching the target location, where we’d often be attempting the hard arrest of a terrorist leader, there was no point being in that bubble of fear either. That would be a lengthy walk in complete silence through the darkness – several hours of relative safety. It was only when I actually got onto target, where the bad guys were, that it was really appropriate to feel scared.

From my very next mission onwards I put this coldly rational approach to fear into practice. I tried to make it a cast-iron rule. The proper time to feel scared was when we were inside the process of an active operation. At all other times, I told myself, the fear was irrational. Pointless. So shake it off.

And it worked. Kind of. As soon as we hit the target, the fear would take me. I’d be inside that bubble, gripped with absolutely gut-wrenching dread until we were done. After the completion of the mission I’d run on to the helicopter, and the moment the door had closed and we’d lifted off to a safe altitude I’d be out of the bubble. Happy. Elated. Delirious. Thank God. And I wouldn’t allow myself to feel fear again until the next mission was in play.

But after a couple of months of this the old feeling started to return. As much as I genuinely loved being a Special Forces operator, the grinding, bubbling sensation in the pit of my stomach when I thought about getting on that helicopter came back. Brutal honesty. I was shit scared. Again. Although I’d managed to break the fear down into a much smaller and more rational chunk, I realised that even that was too much for me to handle. An active operation could last many hours – and sometimes stretch into days, depending on how bad the situation became. That was too long to spend inside a fear bubble.

The next step was obvious. I’d have to break it down into even smaller packets. From now on, I told myself, I would be absolutely rational and clear-headed about when it was appropriate to feel fear and when it wasn’t. Even when I was standing right in front of the terrorist’s compound, I decided, I didn’t need to be in that bubble. After all, he was probably fast asleep with his thumb in his mouth and his dick in his hand, and his guards would most likely be completely unaware of our presence. So what was the point of feeling fear? There was nothing to be scared of. I was a ghost, at that moment, as invisible as a subtle change in the breeze. It was only when I was under a direct threat – when I knew, for example, that there was a sentry position or an armed guard behind a corner or a door that I was stacked right up against – that it was actually appropriate to feel fear. That precise moment before the bullets flew. That was the time.

It was on the next operation that I had my huge breakthrough. We’d entered a terrorist compound at just gone four in the morning. I knew there was an armed combatant just around the corner of a mud and rock wall that I was approaching. I could see the smoke from his cigarette and the black steel barrel-tip of his AK47 in the green static blur of my night-vision goggles. I looked at the corner and told myself, ‘That is where the fear bubble is.’ And then I did something new. I visualised the bubble. I could actually see the fear, right there at the place where my life would be in danger. Not where I was standing, ten metres away from it, but over there where the threat actually, truly was. And nor was that fear happening right now, at this moment. I would feel it a few seconds later, when I made the conscious decision to go over there and step into the bubble.

That visualisation changed everything. Fear was no longer a vague, fuzzy concept with the power to utterly overwhelm me like an endless storm. Fear was a place. And fear was a time. That place was not here. And that time was not now. It was over there. I could see it. Shimmering and glinting and throbbing and grinding, and waiting patiently for my arrival.

Now all I had to do was step into it. I girded myself with a deep breath. And then I took a few paces forwards and walked into it. There it was. Fuck. The fear hit me like wave. I was so close to the enemy combatant I could practically smell the stale camel milk on his breath. Now I was in the bubble, I had to act. I made the conscious decision to do what needed to be done.

The moment he hit the dirt, my fear bubble burst. I stepped forward, around the body, as the relief and elation that I was actually still alive ripped through me. Gathering myself together, I saw that I was now in a wider courtyard area. Out of the corner of my eye I glimpsed someone running into a doorway, slamming the door behind him. I felt a sudden surge of fear and then squashed it dead. ‘I’m now in this courtyard alone,’ I thought to myself. ‘There’s no danger in this physical location or at this precise time. I’m good. Right now, in this place, at this moment, I’m safe.’

I looked at the door. Behind it lay the enemy. Behind it lay the danger. I visualised the bubble right outside it. I approached the bubble. I took a deep breath. I stepped into it and felt the wave of dread slam into me. I composed myself. Kicked the door down. Entered. Cleared the room. And I was out of the bubble again. And that’s how the entire operation continued. When the next target was coming up, I visualised the bubble, stepped into it and felt the fear, committed myself to doing what had to be done and acted. Then, with a wave of bodily pleasure, the fear bubble burst. All I had to do then was look for the next one.

THE POWER OF ADRENALINE

That night I managed to break my experiences of fear down into episodes that lasted mere minutes – and sometimes just a few seconds. Whereas I’d once treated entire six-month tours as enormous, life-sapping fear bubbles, I’d now reduced them to manageable packets and made my relationship with fear completely rational and functional. I realised that while it was surely impossible not to feel fear, it was certainly possible to contain it. It was just a case of working out exactly where the fear was in space and time, then visualising it, before making a conscious choice to step into it and – finally – doing what had to be done.

If it was a surprise how effectively this technique enabled me to manage extreme fear, it was an even bigger surprise to find that it actually made what had sometimes been a horrendous experience almost addictively enjoyable. There was no greater feeling than popping one of those bubbles by going out the other side of it. As soon as I did, I’d experience a surge of adrenaline. I’d use the massive buzz that my adrenaline gave me to propel myself from bubble to bubble. Before long I was running around like a lunatic, looking for the next bubble. Soon, rather than dreading the next moment of danger, I actually began craving it.

People often get fear mixed up with its adrenaline-soaked aftermath. It’s important to understand that these are two separate states of mind. It’s not uncommon for individuals to confuse one with the other and conclude that they’ve conquered fear. Instead, adrenaline is a tool. It’s a temporary high that powers you on to the next bubble and the next bubble, providing you with the energy and the confidence to keep on going, and giving you the natural high of the reward when you pop each one.

As that tour of duty continued, I began to work out more and more about the fear bubble technique. The final critical lesson I learned was that I didn’t have to pop every single bubble that I stepped into. Sometimes I’d enter a bubble, feel all those familiar emotions and sensations blasting up through me, then realise that I wasn’t ready for it. It was too much. When operational conditions allowed, I’d step out of the bubble again, take a moment to compose myself and try again. I realised that it was extremely important not to remain in any fear bubble for too long. If I did, those dreadful emotions and sensations would start to drain me. They’d become overwhelming. Then I’d start overthinking my situation and the fear would just grab me and hold me there, frozen to the spot, as all my courage began to weep away. I had to consciously commit to whatever action was necessary to make that bubble pop. If I couldn’t do that, I’d step back out of it. Take a moment. Have another go. Too much still? No problem. Step out of it again. Two or three attempts was usually all it took. Ultimately, no bubble ever proved too difficult for me to burst.

TAKING THE BUBBLE HOME

The fear bubble technique not only got me through that tour, it prevented the feeling of dread I’d always experienced between operations from ever coming back. Now that I had my fear compartmentalised and rationalised, and I’d learned to use the natural power of adrenaline to sail me from bubble to bubble, I began to actively look forward to getting out there. My professional life became all about bursting those bubbles. As it did, my performance on the battlefield sky-rocketed. I became a better operator than I’d ever dreamed possible.

And then I returned home. By the time I left the Special Forces, the fear bubble technique had become something that I’d do almost subconsciously. It was just how I handled myself and the various challenges that life threw up. I never considered that it would be transferable to other people until one day I received a message from a sixteen-year-old boy called Lucas who was doing his GCSEs.

After the first series of SAS: Who Dares Wins was broadcast, it became normal for me to receive hundreds of messages every week, many of them from young men with various questions about mindset. Often they wanted to join the military or were simply looking for advice on how to cope with certain difficult situations they had coming up. Sadly, I’m only able to respond to a small fraction of these appeals for help. But Lucas sent me a message via social media that I couldn’t ignore.

‘I just don’t want to be on this planet any more,’ he wrote.

‘What’s wrong?’ I replied.

‘I’ve got my GCSEs coming up. I’m stressing out. I’m better off not being here. I can’t deal with it.’

‘Where are you?’

‘I’m at home.’

‘If you’re at home, why are you in that bubble of fear? If you want to get up and have a can of Coke and talk to your parents, you can do that. At this place and time you’re in control. You don’t need to be in that bubble now. Don’t put that pressure on yourself. Even the day of your exams, when you’re on your way to school, you don’t need to be in that bubble. Even when you open the classroom door and you sit down with the exam paper in front of you, you don’t need to be in that bubble. The moment control gets taken away from you and the clock starts ticking, that’s when you need to get in the bubble. Attack Question 1 with a bubble. Once you’re done with that, come out of it, enjoy the adrenaline, compose yourself, and attack Question 2 with a fresh bubble.’

After I’d properly laid out my own method for dealing with fearful situations, he asked me, ‘But why don’t I just stay in that bubble for all fifty questions?’

‘Because you’ll be in it for too long,’ I explained. ‘What happens if you only know 50 per cent of Question 1? All you’re going to do is drag that bubble over to Question 2 and then it’s going to negatively affect your performance on that question. And what if you don’t know Question 2? The fear will build and build. The negativity will build and build. I guarantee you won’t get to Question 10 without your mind starting to frazzle and you losing the plot.’

A couple of weeks later Lucas got back in touch. He had tried my fear bubble technique. And he’d nailed his exam. But it was what he told me afterwards that really got me excited. He said, ‘Ant, I loved going from bubble to bubble. It actually made me enjoy the exam.’

I couldn’t believe what I was reading. I thought, ‘So did I! I used to run around the battlefield looking for the next bubble to get into.’ Not only that, but Lucas’s performance was dramatically improved by his use of the technique. He reported that his time appreciation was much better and that he actually finished the exam ten minutes early. He came out of his final bubble, looked around and saw that everyone else was still heads down and deep in it.

Hearing all this from Lucas was simply incredible. I never dreamed that this little hack that I’d worked out years previously on a foreign battlefield as a terrified soldier engaging in brutal firefight after brutal firefight could possibly transfer to a GSCE exam hall in Bolton. It was only then that it occurred to me that the technique might have the power to transform other people’s lives, just as it had transformed my own.

Eagle-eyed fans of SAS: Who Dares Wins might have seen its powerful effects in a famous scene from Series 2. After my experience with Lucas, I thought I’d see if the technique could help the recruits get through some of the tough challenges we throw at them. One capable young contestant called Moses Adeyemi confessed that he was scared of heights and water. Unfortunately for Moses, heights and water were pretty much all we had planned for him in that series. One morning we brought the contestants to a large river into which they’d have to perform a backwards dive from a high platform that we’d erected on top of a shipping container. The moment Moses saw what we had in store for him he began shaking like a leaf.

What the producers of the programme don’t have time to show is that, as well as bawling at the contestants and pushing them and punishing them, we also mentor them. When I saw the state that Moses was whipping himself into, I decided to take him off for a couple of minutes and explain the fear bubble technique to him.

‘Why are you shaking now?’ I asked him. ‘You’re not in any danger whatsoever. The bubble is on the end of that platform. It’s at a place and a time that is not here and is not now. So fucking calm down.’

As I was speaking, Moses was so busy shaking that I thought it was all going completely over his head. But when he walked along the platform a few minutes later, he did so with utter confidence, as if he owned the bloody thing. I watched him get to the very edge, turn around and wobble. That’s when I knew he’d grasped it. He was in the bubble. The fear was hitting him.

‘You’ve got this,’ I told him.

He tapped his chest three times and muttered something to himself. In that moment I could see that he’d committed. There was no going back now.

And then he dropped. When he was dragged out of the water a couple of minutes later and hauled into the waiting boat, he looked as if he was wired on some sort of illegal drug.

‘Easy!’ he shouted. ‘Fucking easy!’

If I’d asked him to, I’d bet good money that he’d have gladly climbed right back up there and done it all over again.

It’s because of my experience with Moses that, whenever we have contestants on SAS: Who Dares Wins who have to do something heady like abseil off a cliff, I take the time to talk the really scared ones through the method.

‘There’s no point standing back here shaking,’ I tell them. ‘You’re wasting your resources. If you keep on thinking like this you won’t even get to the edge. Walk up to it, acknowledge the bubble, visualise it, get in it – and then walk back out of it, if you have to. Leave the bubble where it belongs.’

It gets people through, almost every single time. And Moses? That man who was afraid of heights and water, and was lost and trembling in a world of fear filled with heights and water? He ended up being the last man standing, the only one to make it to the very end of that series.

When you make yourself aware of these patterns, you start seeing them everywhere. For example, when people do a bungee jump, they’re always terrified before they leap but as soon as the rope takes their weight they’re instantly elated. They want to do another jump and then another jump. What’s happening is that they’re going into the fear bubble, bursting it, and then hitting an adrenaline buzz. That buzz is then pushing them to want to go back into another bubble. When they do go back into that bubble, and do another jump, they’re still going to experience a horrible, gut-wrenching dread just before they leap, but this time they know that the moment they pierce it they’ll get an instant, massive reward. In this way, bungee jumpers are going through exactly the same process as me on the battlefield, Lucas in the exam hall and Moses in the Ecuadorian rainforest. It becomes enjoyable. It becomes addictive.

THE CORRIDOR

This is when it starts changing your life. When you manage to harness the power of your own fear and go looking for bubbles to pop, amazing things begin to happen. For me, one of these life-changing events took place after I’d left the Special Forces. I’d found some interesting work to do that ended up taking me right across Africa. I spent most of my time on the western side of the continent, in countries such as Senegal, Ivory Coast and Sierra Leone, but every now and then I’d bounce eastwards to Burundi. Often I’d be training government troops in surveillance, counter-surveillance and sniping. One day I found myself working with a team of snipers in Sierra Leone that were about to deploy to Somalia. I was in a troop shelter, unloading their weapons, when my phone rang. It was a withheld number. After hesitating for a moment I decided to answer. On the other end was a posh voice I didn’t recognise.

‘Are you Ant Middleton?’

‘Yes, Ant Middleton speaking.’

‘I hear you’re the man for the job.’

Who was this joker? After you leave the Special Forces you become used to being approached by all sorts of shady characters offering you all sorts of shady work. You quickly develop an instinct for who’s the real deal, and who are the idiots. The first tell is this – the idiots talk as if they’re in a bad Guy Ritchie movie. Still, I thought, I might as well hear this one out. To my surprise, he turned out to be an executive from a TV production company. He explained that they were planning on creating a major show in which twenty-five to thirty ordinary men would be put through a condensed version of Special Forces selection. He’d heard I was about the right age bracket and had the right experience. Was I interested in trying out for it, as one of the directing staff?

‘I’ll call you back,’ I said.

My immediate instinct told me that this was a definite no. At that time I was living completely in the shadows. I wasn’t on social media, I wasn’t in the phone book, I wasn’t even on the electoral roll. I was bouncing around Africa, a continent that I love, doing well-paid work, and the only person who knew my whereabouts was my wife Emilie. I was happy with that. Very happy indeed. And, besides, it wasn’t seen as the done thing for a Special Forces man to step out of the shadows. What were the lads going to think? How would they take it? When I began to think about the potential ramifications of a television career, a thousand questions suddenly flooded in. I felt my heart begin to pound.