Полная версия

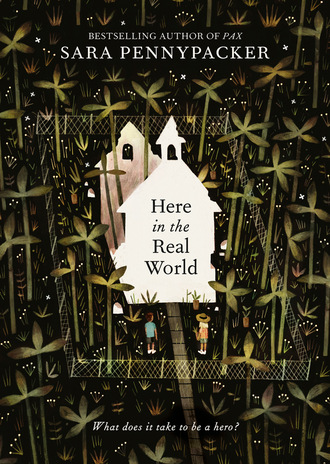

Here in the Real World

Ware glanced over toward the church. At the top of the baptistery, a slice of turquoise flashed like a greeting.

Lying in bed, trying to forget what he’d overheard his mother say, he’d thought about that do-over tub a lot. He could really use a brand-new-self fresh start like that.

He dropped to the ground, strode over to the girl, stood in front of her. “How does it work? Getting born again?”

“I told you. Dunking.” She stabbed her trowel down next to his sneaker, a warning.

Ware took a step back. “I mean . . . the people. They weren’t trying to turn into babies again, so how is it supposed to work for them?”

The girl blew her bangs out of her eyes. “They get reborn on the inside, not the outside.”

For the second time in as many days, Ware remembered the laughing counselor. No, I mean inside the group. You’re outside.

He shook it off. The outside was part of the inside.

“Right. Is everything changed, or just the bad stuff?”

“Just the bad.”

“And people liked them better afterward, right?”

“Of course,” the girl said. But she didn’t sound quite as sure.

“Is the tub magic, or the water?”

“The water. Except it wasn’t, remember? I told you it didn’t work. People went right back to their old selves.”

“Everybody? Nobody stayed shiny and new?”

The girl balanced her trowel on one sharp knee. She sat perfectly still except that her toes stretched in her pink flip-flops, as if they were reaching for the answer to his question. “I don’t know,” she admitted. “I guess I only know about one person that didn’t stay born again.”

“So it could work,” Ware pressed. “It must work for some people, or else it wouldn’t be a thing.”

“Maybe.” She picked up her trowel.

“Wait. The magic holy water. Was it holy to begin with, or did it get holy by being in the tub?”

“It has a regular faucet. I guess the preacher did something to it.”

“What? What did they do?”

The girl blew her lips out so hard her bangs flew straight up. “Who cares? It’s over! Whatever it was got packed up and left. Look around,” she ordered. “There’s no holy here. No magic.”

Ware looked. Everything, everywhere, was broken.

Then his gaze fell upon the garden. On the plants in their rusted tin cans—feathery but brave at the same time. At the bigger plants, sturdy in their row.

The girl saw where he was looking. “Nuh-uh. They’re better than magic. You can count on them.” She lifted her sunglasses and squinted at him. “Why are you so interested, anyway? I thought you said this was a castle. In case you didn’t know it, castles don’t have baptisteries.”

“So . . . right. I know.” Ware drew back. He suddenly felt protective about his do-over wish. As if it was feathery and brave at the same time. “But, um, ha-ha, they have moats,” he joked. He added a shrug to show that he didn’t really care, anyway.

“Well, far as I know, moats go outside a castle, not inside,” she muttered.

And for the third time, Ware thought of that laughing counselor. He left the girl grumbling beside her plants, climbed the foundation, and headed to the do-over tub.

Eleven

Ware climbed the steps he’d found at the back of the baptistery and sat on the rim. He imagined the tub full of water, imagined falling into it and then stepping out a less disappointing son whose report cards said, Ware is extremely social! And also, very normal!

What would a change like that feel like? Would it hurt to feel your old self being kicked out? What if his old self put up a fight, or refused to budge?

At a smack on the side of the tub, he opened his eyes.

The girl again. Unbelievable. She swept off her shades and glared up.

Ware was reminded of his report. Castle battlements were slotted with narrow openings called arrow slits, through which guards could shoot approaching enemies without being targets themselves. Ware got the impression that the girl’s blue eyes functioned pretty much the same way.

She narrowed her arrow-slit eyes, but she was wearing a sly half smile. “How would you fill this thing?”

He gestured to the faucet.

“Nuh-uh. The city shut it off. So how would you get the water here?”

Ware looked over at the Rec Center and shuddered. Maybe the library would lend him some. “Oh, buckets,” he tried in a casual tone. He tossed out a window screen.

“Nope. Hose, that’s how. You got one?”

“Do I . . . ?”

“I got a hose. Fifty feet.” She waved her sunglasses back toward the Grotto Bar.

“You live in a bar?”

“Above it. Fifty feet’s not enough. It just reaches to the fence. You got a hose or not?”

“I don’t know. Maybe.”

“Maybe? Well, you bring me enough hose to reach my garden and this tub, maybe I won’t throw you out of here.” She put on her glasses and settled them firmly on her nose.

“Maybe you won’t throw me . . . ?” Ware carefully straightened up to standing on the baptistery’s rim. Height was an advantage in medieval warfare. “Who do you think you are, anyway?” his reckless self challenged.

The girl pursed her lips and tapped them with a grubby finger, pretending to think hard about whether to divulge this extremely important information. Then she shrugged. “Jolene.”

The baptistery’s rim was narrower than he’d realized. He came down a couple of steps. “Okay.”

“Okay, what?”

“Okay, maybe I’ll bring a hose tomorrow.”

He walked past her and scooped up his backpack.

The girl followed him and jumped off the wooden-door drawbridge when he did. “Hey,” she yelled as he took off for the big oak. “What’s your name?”

Ware called it back to her and kept walking.

“Where? Here. What’s your name here?”

Ware was used to this. On their first date, his parents had discovered they each had a great-great-great grand-father who’d fought at the Battle of Ware Bottom Church in the Civil War—on opposite sides. It hurt his head to think about his ancestors shooting at each other, having no idea they’d share a great-great-great-great grandson—what if one of them had been a better aim?—but mostly he was glad his parents hadn’t decided to commemorate the coincidence by naming their kid Bottom.

He took a few steps back. “Not where,” he explained, whooshing the h. “Ware. With an A.”

“Okay, Ware. Bring that hose. It doesn’t mean you can have the church, though. I haven’t decided.” She pulled her hat out of a pocket and tugged it on.

Ware felt his jaw drop at the unfairness. He really hated unfairness. He wanted to say something stinging back at her, but before she’d tugged her hat down, her mirror glasses had pulled that trick again. And there he was, still the most pathetic kid in the world. He hadn’t even thought about how he’d fill that do-over tub.

He started toward the Rec again, head down. “Wait,” he heard. He waited.

“What’s ‘Ix’?”

He turned.

The girl was pointing up to the wall by the doorway. “Ix,” she repeated. “What’s it mean?”

“Not Ix. Nine. In Roman numerals.”

“Why?”

He walked back. “They used Roman numerals back in the Middle Ages. And they put sundials on castle walls. See how the shadow is pointing toward the numerals? I made them at nine o’clock yesterday.”

“Oh. So, here”—she tapped the wall—“this is ten o’clock?”

“Around there. But I’d have to be here at ten to make sure.”

She cocked her head at the numerals. “Is that blood?”

Ware nodded miserably.

“Huh,” she said, frowning. She seemed to be trying hard to decide something—for real this time.

Ware took the opportunity to escape. He was nearly to the fence when she ran over to him.

“The parking lot is the boundary. Between my territory and yours. No crossing it. And you can’t tell anyone about this place.”

“What?”

“I decided. You can have the church.”

Twelve

The next morning after his mother drove away, Ware jumped up into the oak and concealed himself in a cloud of leaves, deep as a secret, because the first objective of medieval reconnaissance was to gather information about the enemy.

And in spite of the hand taking with the buzzy feeling, in spite of allowing him the church, that’s what the garden girl was. She’d made that clear. What she didn’t know was that Ware was an expert in castle defense. He’d gotten an A on his report.

The enemy was digging in the shade of the three queen palms. The palms looked like guards today, curving over Jolene protectively.

Ware noted how carefully she placed her foot on the spade before jumping on it, probably so it wouldn’t cut through her flip-flops. The enemy’s inadequate footgear was a clear weakness.

Her trowel jutted out of a back pocket. Obviously gardening was a strength, but strengths, he reminded himself, could be useful as diversionary tactics.

He released his backpack, heavy with a hose he’d found in his shed, and dropped down after it.

Jolene turned at the thud. “The boundary,” she yelled, waving a finger at the parking area.

Ware hoisted the hose like a white flag.

Jolene nodded permission and he crossed, dropped it in front of her. “What are you doing?”

She joggled her free hand through the air, as though hunting for the words to adequately express how deranged his question was.

“I mean, I see what you’re doing. But why?”

Jolene kicked at a pile of dirt. “It’s basically rock dust. I have to dig out a trench and fill it with good soil before I can put in my plants.”

Ware took a step closer. “I mean, why are you doing all this work? What’s so important about these plants?”

Jolene jumped on her shovel again, this time not so carefully. Her hair flopped down like a curtain, but not before Ware had seen her face. She looked frightened.

His hand flew to his chest, the way it always did. The sight of people being frightened literally stole his breath, like a hundred-arrow volley to the lungs, thunk-thunk-thunk.

Mikayla was always stunned at how deeply Ware sensed other people’s pain. “It’s like your superpower,” she said, “feeling what other people are feeling.”

“Right. Captain Empathy,” Ware had joked back. But he hadn’t really thought it was funny. Superpowers weren’t supposed to hurt.

Now he wanted to tell Jolene not to be afraid. But nowhere in his research for his report had he learned that a good castle defense was to tell the enemy not to be afraid.

He backed away and climbed onto the foundation to accomplish the second objective of reconnaissance: location assessment. Location assessment required height, so he picked his way over to the tower. Towers were excellent for getting the whole picture of a place.

The stairway, he noted as he climbed, spiraled the wrong way, at least for real medieval castles. Real castle stairways wound up counter-clockwise so that the castle defenders, streaming down from the top, would have their right arms free to do battle with the ascending attackers, who would have their sword arms to the wall.

But Ware was left-handed. The clockwise spiral felt like a sign. This place was meant for him.

Which was crazy, of course.

From the top of the tower—which wasn’t exactly towering, maybe twenty feet high—he did get the whole picture of the place.

The lot was almost as big as a football field, and protected from view all the way around, the way castles were protected by their outer curtain walls. The side boundaries—east and west—were six-foot board fences, while the north boundary in the back had even taller evergreen hedges. All of First Street was marked Glory Alliance Parking Only! and the bank had erected a tall chain-link fence covered in orange mesh and warning signs across the front lawn. The same construction fencing had gone up across the driveway in the back that led to the small parking area. Even the nosiest person pressing an eye to that fencing would have a hard time seeing what went on in the lot.

Ware looked down at Jolene. She was dabbing her trowel over each plant down the row, like a fairy godmother bestowing blessings with her wand. And then he realized: She wasn’t blessing her plants, she was counting them. As if they could have grown legs and escaped during the night.

When she picked up the hose and began to water them, it dawned on him: If he wanted to try out that do-over tub—and he did, although he’d have to keep it secret from her, of course—he had the upper hand now, thanks to that hose. She’d have to tell him whatever she knew about the holy water deal.

He hurried down the tower stairs, jumped off the back of the foundation. Chin up, chest out, he advanced boldly into her territory.

Thirteen

“This good soil you need,” Ware said, employing Jolene’s strength as a diversionary tactic before sneaking into the holy water issue. “Where are you going to get it?”

Jolene nodded approvingly at the question. She twisted the hose nozzle off and waved toward three waist-high heaps he hadn’t noticed before.

The piles were layered with food in various stages of rot. Banana peels, orange and watermelon rinds, some greenish stuff that must have once been vegetables. “Garbage?”

“It was,” she agreed. “It’s turning into compost.”

Ware hitched his eyebrows into a look that he hoped conveyed sufficient wonder. “Compost. Great. Now, what did the preacher do to make the water holy?”

She tipped her head to the fence behind the piles. “I go to the Greek Market next door and get the fruits and vegetables too old to sell. I shovel some dirt over them and the worms do the rest. Now, the Chinese were the first to compost, back in 2000 BC, and . . .”

Ware started to zone out, but when the sun pulled out of the queen palm fronds and hit her mirror glasses, it jolted him.

At his grandmother’s place, Ware had gotten up at dawn to have the pool to himself. That early, the water would flash blindingly, like those glasses. No matter how hard he’d tried to peer down into it, he’d only seen his own face reflected back. Sometimes, yourself was exactly what you didn’t want to see.

“Oh,” he said, a little unnerved for a moment. “So . . . the preacher. Was it a spell?”

“Look. I only snuck in once. I heard some words that sounded important.” Jolene pushed her hat up and studied his head for a thoughtful moment. “You look like you’re rusting.”

Ware rubbed his hair. He knew it was unusual—his mom’s tight waves, his dad’s dark copper color. But the summer sun bleached it bronze, and three weeks of chlorine at Sunset Palms hadn’t helped. “I know,” he said. “But what about—”

Jolene flapped her trowel at him dismissively. “No offense. My freckles look greenish in the sun. Now, there are three piles because they’re in different stages—”

They both turned at the shriek of a whistle.

The Rec kids were outside. They began to cheer.

“Rec-re-ation

On va-cation

We’re fun-nation

Go, Rec, GO!”

Several times a day the campers were gathered in a circle to link arms for something called Rec Spirit. Ware hadn’t liked the shouting, and he’d never understood the cheer.

At home after his first day, he’d asked his mother what recreation meant.

“Play. You know, things you do for fun. Not work.”

None of those definitions applied to the day he’d just had. “How about funnation? What does that mean?”

“It’s not a word,” she’d said. “You must have heard it wrong.”

He’d listened carefully the next day, and when he heard the word again, he’d unhooked an elbow and raised his hand. “Is it Fun Nation? Or fun-ation?” The counselor had just stared at him. “It’s funnation,” she’d said unhelpfully. “So it rhymes.”

From then, he’d shouted the cheer along with everyone else, but it always left him feeling vaguely embarrassed.

“Hey, wake up.” Jolene waggled her fingers toward the Rec. “You have to go. Bye.”

“Not yet.” Ware heard the words as if it had come from someone else. “First, I have something important to do.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.