Полная версия

Emperors of the Deep

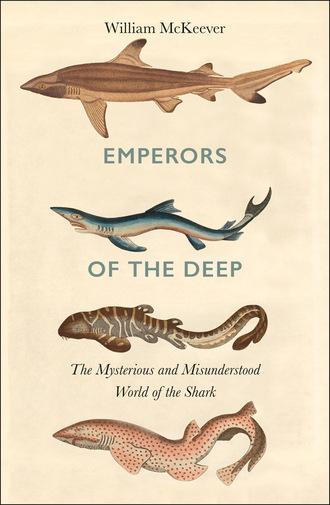

EMPERORS OF THE DEEP

The Mysterious and Misunderstood World of the Shark

William McKeever

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2020

First published in the United States by HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers in 2019

Copyright © William McKeever 2019

Images © Individual copyright holders

Photograph here: Ocean sharks by anas sodki/Shutterstock

William McKeever asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Jacket illustration copyright Purix Verlag Volker Christen / Bridgeman Images

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780008359164

Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008359188

Version: 2020-06-08

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

INTRODUCTION Man Bites Shark

CHAPTER 1 Searching for Mary Lee

CHAPTER 2 Makos, the F-35 of Sharks

CHAPTER 3 The Mysterious Case of the Hammerhead

CHAPTER 4 Sharks as Social Animals

CHAPTER 5 The Quest for the Tiger Shark

CHAPTER 6 The Shark Attack Files

CHAPTER 7 The Sex Lives of Sharks

CHAPTER 8 Bearing Witness

CHAPTER 9 Human Trafficking at Sea

CHAPTER 10 Water, Water Everywhere and Not a Tiger in Sight

CHAPTER 11 The High Seas

CHAPTER 12 Shark Warriors

CHAPTER 13 Shark Alley

CHAPTER 14 Save the Shark

Picture Section

Notes

Acknowledgments

About the Book

About the Author

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

MAN BITES SHARK

I REMEMBER MY FIRST EXPERIENCE IN THE OCEAN. ABOUT five years old, I was with my dad, anchored to his broad shoulders. He swam us out past the break, which offered me a panoramic view of the beach, the surf, the distant horizon: a new vantage point that heightened the ocean’s tremendous beauty.

My dad liked to swim when the surf was strong, with the waves pounding the shoreline, the kind of surf that the lifeguards warn against taking on. My dad always wanted to test his strength against the waves, to see if the crashing wall of water could knock him off his feet. Most of the time he was left standing. Watching him, I tried to do the same thing, just as any boy might try to emulate his father. One day, when I was ten, the waves were surging, and I summoned the courage to test them. The first wave picked me up and tossed me like a woobie in the wash. I somersaulted and rolled inside the wave, helplessly ransomed in its grasp, until it was ready to spit me out. The sensation of being roiled and tossed and turned and thrown around was totally new. Rather than being scared out of the water forever, I held on to the feeling. I could never predict which way the wave was going to send me, an arm this way, a leg that way, a disorienting feeling I continue to associate with the power of nature. Though a constant source of joy and play for millions of people around the world every day, the ocean was always in charge.

My dad and I would go fishing, and the water wasn’t always rough. Out at sea in our skiff in Nantucket Sound, south of Cape Cod, we were in prime territory to land big fish. When my father was ready to cast a line, he’d cut the engine, and we’d drift. I remember listening to the sound of the waves lapping the hull of our boat and the wind blowing through my ears as the boat rocked gently in the water. After a day of fishing, a ghostly swaying in my legs followed me to bed. Sometimes, as I looked out over the sea, I would see a dark spot just below the surface, jutting this way and that. Every now and again, I could clearly make out a shark, its beautiful dorsal fin slicing through the water. Once, my father caught a dogfish shark, a skinny bottom-dweller, about two or three feet long. I remember being struck by how vulnerable the shark looked, thrashing on the boat deck, desperate for oxygen and an escape route back into the water. Though the dogfish is edible, I pleaded with my father to let the shark go. My father gave in, and I was glad to see the fish swim away, rejoining, I hoped, its family and all the other mysterious creatures swimming deep below the surface.

Those fishing experiences with my dad deepened my appreciation of the ocean and the majestic creatures that inhabit its unseeable depths. When summer ended and the school year started, I went to the library and read every book I could find about sharks. I wanted to learn about how sharks operate, how they live their lives. I wanted to know what sharks were really like. But every book I picked up portrayed them as killers. On television and on the big screen, too, sharks were cast as man-eaters, out-of-control predators. A character would go swimming in a movie, and a shark would come along and take his leg off. Conversely, dolphins were never portrayed as anything other than pure gold, like an honor student at school, the paradigm of good behavior.

Slowly but surely, the prejudice against sharks started to seep into my consciousness. I respected sharks as much as I respected the ocean. Both were beautiful and powerful and, I understood even at a young age, in full control—I and all the other swimmers and fishermen were simply visitors to the underwater empire, vacationers, day-trippers, tourists. While my reverence for the ocean included a deep appreciation of its unpredictable power, my admiration for sharks was less sincere, tinged with suspicion and an almost irrational fear. Though I knew I was psyching myself out, every time I went into the ocean I couldn’t help but worry that a shark attack was just a few yards away.

As I quickly learned, I was not alone in this fear.

Continuing my research of sharks, I came across what many consider the event that instilled in the American psyche our widespread cultural fear of sharks. It occurred in the summer of 1916. Over a horrifying ten-day period, four people were killed in the water, and one was seriously injured. The events triggered mass hysteria and, as far as I could determine, the first extensive shark hunt in history. Victim One was attacked on July 2 at Beach Haven, New Jersey. Four days later, 45 miles north, a second victim was attacked in Sea Girt, New Jersey. Immediately, hundreds of people took to their boats, armed with nets, guns, and dynamite. Many sharks were killed, each one identified as the man-eater. When the next three attacks took place on July 12—this time in Matawan Creek, 70 miles north of Beach Haven—it became clear that none of the captured sharks was responsible. A taxidermist finally claimed to identify the great white culprit after finding a child’s shinbone and what appeared to be a human rib in the shark’s stomach. Ever since, however, many have questioned the taxidermist’s theory, pointing out that because great whites cannot survive in fresh water, a single great white couldn’t have killed the three people in Matawan Creek, a freshwater tidal inlet. (A bull shark is the only shark species that can swim in both salt and fresh water.) While it’s likely a great white was responsible for the attack in the saltwater Raritan Bay, the freshwater attacks rule out a deranged, man-eating great white on the loose.

And yet, the single-shark conspiracy prevailed, a questionable-at-best theory that nevertheless served as the basis of a bestselling book, the most famous book ever written about sharks: Peter Benchley’s Jaws. Since its publication in 1974, Benchley’s novel has sold 20 million copies and has likely shaped our perception of sharks, and great whites in particular. When Steven Spielberg released his cinematic adaptation two summers later, the film locked into place the public’s intractable fear of sharks. Jaws sparked a period of great interest in great whites and established the unsubstantiated belief that sharks as a species are nothing more than bloodthirsty man-eaters, apex predators with no other purpose than to kill. The movie certainly had that effect on me. That opening scene—in which a young woman is attacked and mercilessly thrashed about—made me think twice, as the tagline promised, about ever going in the water again. From the summer of ’76 on, whenever I stepped into the ocean, the unsettling specter of sharks scuttled across the deep recesses of my mind, a twitch of fear I tried to ignore while splashing in the surf.

Little did I know that sharks have more to fear than humans. And unlike our fear of them, their fear is justified.

A FEW YEARS AGO, I WAS SPENDING THE WEEKEND IN MONTAUK, New York, a tony community in the Hamptons on the far eastern part of Long Island. Wandering around the marina, I noticed a large crowd gathered around one of the many fishing boats docked there. To my shock, everyone was gawking at a number of dead sharks strewn about the wooden boards, remnants of a recently concluded shark tournament. One shark—a blue shark about 8 feet long—caught my attention. The shark was on full display, its white underbelly exposed, bisected by the marine blue of its body’s upper half. Its mouth was gaping open, and a hook protruded from the corner of its mouth. Its internal eyelid had drooped over its eye, which reminded me of a sheet placed over a dead man in a morgue, an appropriate image because I couldn’t escape the sensation that I was visiting a murder scene. All these dead sharks had been tossed away like garbage. The sheer number of them on the dock that day rivaled the scene’s brutality.

As I slowly retreated from the marina, a knot formed in my stomach. I couldn’t help but wonder: If fishermen were killing this many sharks during one weekend on Long Island, how many sharks are dying at similar tournaments around the world? No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t shake the feeling that sharks were in trouble—a feeling I confirmed once I started looking into the numbers. While sharks kill an average of four humans a year, humans kill 100 million sharks each year. That is not a typo. Humans kill 100 million sharks each year.

While recreational fishing is doing considerable harm to the shark population around the world, commercial fishing is decimating it. Sharks are harvested throughout the world for their meat, skin, fins, liver, and cartilage.[1] Specifically sharks are killed as a by-product of the $40 billion tuna industry, which provides the United States with enough tuna to feed every American 2.6 pounds per year. Seventy percent of the world’s tuna is harvested from the Pacific Ocean, where regulatory bodies are unconcerned with or overwhelmed by sustainable fishing practices. Over thousands of square miles of blue, thousands of vessels from China and other countries fish for tuna and sharks in what Greenpeace describes as an “industry out of control.” More than five thousand authorized longline vessels are currently operating in the Pacific, and many more aren’t authorized. The preferred method of catching tuna is longline fishing, a remarkable and sadistic practice. Fishing vessels set a single line from the stern of the boat. The length of this line is staggering, up to 100 miles long. Attached to this one line, at regular 10-foot intervals, are baited hooks. A relatively small vessel can set out thousands upon thousands of them. Fishermen leave the line alone overnight, reeling in their catch the next morning. Anything can get caught on that line, including the sharks that are chasing the tuna. In fact, some fisheries catch more sharks than tuna.

And then there are the horrors of “transshipment.” One fishing vessel transfers its catch to another vessel, which then takes the catch to market. This sounds like an efficient way of doing business, but when the transshipment happens at sea, far out of reach of inspection, fishermen can hide what’s really going on. Illegal catch is regularly smuggled with legal catch, and when the entire catch finally reaches shore, there’s no way of knowing which vessel it came from or how the fish were caught. At the same time, the crew is often made up of indentured servants, and transshipment keeps these exploited men out at sea indefinitely, often for years at a time. Forced to work for minimal pay, which is rationed out over a fishing season, the crew does what it can to survive, regularly resorting to finning captured sharks, then selling the pectoral and trademark dorsal fins on the black market or to China, where the demand for shark-fin soup is insatiable. Literally millions of tons of sharks are captured every year to keep up with this demand.

These ships are truly weapons of mass destruction on the high seas.

While it is well known that sharks are killed for their fins to make Chinese soup, they are also killed for their squalene, a key moisturizing agent in cosmetic products like lipstick. While squalene can be extracted from plants, sourcing it from sharks is easier and significantly cheaper. Squalene fisheries operate primarily in the southeastern Atlantic and western Pacific oceans, where regulations are lax.

Some people were quicker than others to recognize this peril, most notably the man most responsible for instilling a fear of sharks in the culture at large. Years after the success of Jaws, author Peter Benchley was scuba diving off Costa Rica when he had an epiphany. Submerged deep beneath the surface, he spotted the corpses of finned sharks littering the bottom of the sea. This scene, which he called one of the most horrifying sights he had ever witnessed, forever changed his life. Sharks were no longer savage leviathans and man-eating monsters; they were now the mutilated victims in this all-too-real horror story. Benchley renounced his contribution to the “momentary spasm of macho shark hunting” and abruptly changed his views on sharks. Reflecting on Jaws, Benchley later wrote that “the shark in an updated version could not be the villain.” He added that if he were to do it all over again, the shark “would have to be written as the victim, for, worldwide, sharks are much more the oppressed than the oppressors.”[2] Benchley could not escape the carnage that ensued in the wake of his book, and up until his death in 2006, he committed himself to changing the negative perception of sharks and ending their killing.

Today, sharks are under the greatest threat in their entire 450-million-year history. Despite the fact that they play an essential role in maintaining the delicate balance of the marine ecosystem and are key indicators of the overall health of our oceans, sharks are not a priority for conservation. In any healthy ecosystem, a balance of components is in place, evolved over eons. Once the sharks go, environmental repercussions will occur everywhere, from the frigid waters of the Arctic Circle to the coral reefs of the tropical Central Pacific. Taking away apex predators typically results in top-down impacts on the ecosystem. Studies have shown that coral reef ecosystems with high numbers of apex predators tend to have greater biodiversity and higher densities of individual species. A healthy coral system, for instance, requires a similarly healthy shark population, which, in turn, balances the herbivores and the fish that prey on them. Without sharks, the entire ecosystem of the coral reef collapses. Moreover, healthy shark populations may aid in the recovery of damaged coral reefs, whose futures are threatened throughout the globe.

Sharks are being decimated around the world by tuna fishing and finning and even local shark tournaments like the one I encountered in the Hamptons. From a biological viewpoint, the shark population isn’t built to withstand the onslaught. With long reproductive and gestation periods, sharks simply can’t reproduce fast enough to replace the losses. Kill the sharks, and humankind cripples the seas.

The sudden vulnerability of sharks—a species that has survived five extinction-level events, including the one that killed the dinosaurs—calls for a complete reinterpretation of our relationship with them. That’s the goal of this book. I want to shift the perception of sharks from cold-blooded underwater predators to evolutionary marvels that play an integral part in maintaining the health of the world’s oceans, because this is the only way I know how to protect the species and save the world’s oceans. This is a continuation of my work at Safeguard the Seas, the ocean conservancy I founded in 2019 to use activism, advocacy, and education to protect sharks and other fish threatened by man. Contra Jaws, I have figured out the only way to change the way we think about sharks is to cast the species in an entirely new light, in all of their underwater glory, and share with a general audience the emerging science of sharks, which is slowly pulling back the curtain on one of the ocean’s fiercest predators. Thanks to new technologies that allow scientists and marine biologists around the world to track sharks like never before, we have made great strides in recent years in understanding the species, including their mysterious underwater behavior, their supernatural migratory patterns, their remarkable social ability, and even their secret sex lives.

To understand these new discoveries, I visited the top oceanographic research institutions in the world, interviewing today’s leading scientists and conservationists, from Cape Cod to Cape Town, from the Florida Keys to Australia’s Shark Bay, with stops in between. These pioneers broke down for me this emerging science of sharks and shared many of the species’ most closely guarded secrets. At the same time, I tagged along with Greenpeace activists in Busan, South Korea, to learn about the organization’s most recent “bearing witness” campaign and to tour the Rainbow Warrior, the organization’s iconic ship. I also met with courageous artists and relentless activists around the world who, like me, are trying to change the public’s perception of sharks through creative marketing campaigns and daring exhibitions in Miami and Mossel Bay, South Africa. To get a better sense of how the international fishing industry traffic operates, I interviewed six former slaves-at-sea in Cambodia. Closer to home, I spent a day with the self-professed “last great shark hunter” and went to a mako-only shark tournament in Montauk, the Super Bowl of shark contests, to understand why recreational fishermen continue to hunt sharks for sport, despite their declining numbers. And finally, to get a close-up view of the world’s most feared and most misunderstood predator, I stepped freely into their environment, emboldened this time to share the water with the species that has fascinated me since I was a child.

While much has been uncovered about sharks in recent years, there is still much to learn about them—or unlearn in the case of our popular misconceptions about them. Though hardly comprehensive, this book is a culmination of my two-year journey, at once a deep dive into the misunderstood world of sharks and an urgent call to protect them, a celebration of sharks as remarkable apex predators, supersensory navigators, and humankind’s greatest ally in nature, and—as scientists begin to learn more about them and their behavior—quite possibly the key to unlocking the mysteries of the ocean. That is, if we don’t kill them off first.

Though I focus primarily on the Big Four—great white, mako, hammerhead, and tiger—the ocean is home to approximately five hundred species of sharks, from the epaulette shark, which crawls across the surface of reefs, to the 34-ton whale shark, the ocean’s gentle giant, which motors along at its own pace, consuming 50 pounds of plankton a day. The diversity of the species comes across in its behavior and appearance, its form and function. The bioluminescent catshark, for instance, which glows green in the darkness off the continental shelf, is a stunning specimen. Greenland sharks, which measure 13 to 16 feet in length and weigh 3,000 pounds, may live more than four hundred years,[3] making them the longest-living vertebrate in the world by at least one hundred years. They are also the slowest-moving shark, traveling at 1.6 miles per hour. And while the bull shark lacks the natural good looks of the sleek thresher, a ballerina of a shark, the bull’s internal machinery, which allows it to survive in fresh and salt water, is undoubtedly a thing of beauty. This evolutionary marvel rivals the great white’s deep diving and long-distance traveling abilities, the mako’s perfectly proportioned cylindrical body, the hammerhead’s trademark T-shaped head, and the tensile strength of a tiger’s jaw, which can generate a force of 3 tons per square centimeter, equivalent to the weight of two cars.

Sharks have never been considered beautiful creatures. Yet what all the sharks discussed in this book illustrate is that they are indeed beautiful and majestic, emperors and empresses of the deep, every last one. “If everyone were cast in the same mold,” Darwin famously wrote, “there would be no such thing as beauty.” Because beauty takes shape when one recognizes the diversity of life and comprehends nature’s magnificent design, the experience of it touches the soul. Draped in various shapes and sizes lies a beauty to behold like pearls scattered throughout the world’s oceans. We just have to open our eyes to see the sharks as if for the first time.

CHAPTER 1

SEARCHING FOR MARY LEE

SHORTLY AFTER DAWN ON JUNE 17, 2017, MARY LEE DISAPPEARED off the coast of Beach Haven, New Jersey, a sleepy beach community 20 miles northeast of Atlantic City.

Concern quickly spread among Mary Lee’s 130,000 Twitter followers, a modest but loyal fan base most likely amassed during her numerous high-profile travels around the world: winters in Palm Beach, summers in the Hamptons, and, in between, the occasional jaunt to Bermuda, where she splashed around in the island’s cerulean surf. Wherever Mary Lee went, people followed her every move. Curious beachcombers and paparazzi checked their iPhones for news of her whereabouts and speculated about Mary Lee’s real age, her sudden fluctuations in weight, and even the rumored father of her reported pregnancy.