Полная версия

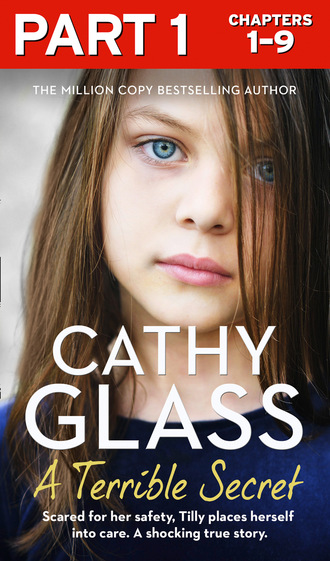

A Terrible Secret: Part 1 of 3

‘No, you don’t, love.’

‘He gets very angry if Mum makes him something he doesn’t like to eat.’

‘Have you told your social worker things like this?’

‘Some, but not all – not about the food.’

‘Mention it next time you talk to her. Call your friends now.’

I would make a note of this and any other disclosures Tilly made about her home life in my log and update her social worker. It might seem a small point now, but it could form part of a bigger picture. All foster carers in the UK are required to keep a daily record of the child or young person they are looking after. This includes appointments, the child’s health and wellbeing, education, significant events and any disclosures. As well as charting the child’s progress, it can act as an aide-mémoire and also be used as evidence in court. When the child leaves this record is placed on file at the social services.

I left Tilly in the living room about to call her friends while I went into the kitchen. Before I began cooking, I messaged my family’s WhatsApp group to let Paula, Lucy and Adrian know Tilly had arrived, so they didn’t just walk in and find her here. Then I set about making the bolognaise sauce for later.

As I worked, I could hear the rise and fall of Tilly’s voice through the open door of the living room as she talked to her friends. She said pretty much the same thing to all of them, recounting the horror of another fight between her mother and Dave, the police arriving, her mother refusing to press charges and defending Dave, being taken to the social services’ offices and then coming to me. One friend must have asked about me, for I heard her say, ‘Yes, she seems OK, and the house is nice. But I worry about Mum.’

I hoped Tilly would find the strength to stay with me for the time being at least, for if she returned home I felt the situation was likely to deteriorate, and there was no guarantee the social services would apply for a court order to remove her. Their resources are stretched to the limit, and with over 70,000 children in care, and more coming in each day, a baby or young child whose life was in danger would probably have priority over a fourteen-year-old who had removed herself from care.

I heard the front door open and Paula return home. I left what I was doing to go into the hall to greet her. ‘So you had some success at the sales then,’ I said, pleased. She was carrying a number of store bags.

‘I’ve spent a fortune!’ she sighed.

I knew she wouldn’t have done. Paula was careful with her money and only bought what she needed after much deliberation. I knew whatever she’d purchased would be a good buy. We went into the living room and I introduced her to Tilly. Tilly finished on the phone and the two girls said a shy hello. It would be some time before we all relaxed around each other.

‘I’m going to get a drink,’ Paula said to Tilly. ‘Would you like one?’

‘Yes, please. I’ll come with you.’ She stood.

I left the two girls to go to the kitchen and I heard cupboard doors opening and closing as Paula showed Tilly where the juice and squashes were and told her to help herself. I’ve found before that the child or young person we foster often bonds with one of my children before they do with me. Presently both girls appeared carrying a glass of juice. ‘I’m going to my room,’ Paula told me.

‘Is it OK if I go to my room?’ Tilly asked.

‘Yes, of course, love. You do as you wish, make yourself at home.’

‘Thank you.’ She followed Paula upstairs and I heard them talking on the landing for a few moments and then go into their own rooms.

Ten minutes later Lucy arrived home, earlier than usual because the staff at the nursery were working shorter shifts in the week between Christmas and the New Year, as they didn’t have many children in. Most companies had closed for the whole week, but the nursery was open with reduced hours.

‘How are you?’ I asked Lucy, as I did every time I saw her. It was a question laden with hidden meaning now, given her condition.

‘OK. I feel fine.’

‘Good.’ She looked it. She hadn’t had any morning sickness so far; indeed, she seemed to be blossoming. ‘I’m going to get a drink of water,’ she said. I followed her into the kitchen.

‘How’s Darren?’ I asked as she ran a glass of water.

‘He wasn’t in work today. There were only three of us, as there are so few children in this week.’

‘But you spoke to him?’

‘He texted. We’re fine, Mum, don’t worry. Where’s Tilly?’

‘In her room.’

‘How is she?’

‘Finding it a bit difficult at present. I’m sure a few words from you would help.’

‘I’ll talk to her.’

‘Thank you, love, I’d appreciate that.’

Lucy went upstairs. Having been a foster child herself, she knew what it felt like to arrive in a stranger’s home and could usually say something to help. I tried not to think of the new life growing within her while she made the difficult decision of whether to go ahead with the pregnancy or not. Abortion is a highly contentious and emotional subject, but for me it has to be the couple’s right to choose. If Lucy decided to have the baby then I would start to think of it as her unborn child. If she didn’t then it would remain a foetus, not a viable life, harsh though that may sound. I love children and have dedicated my life to looking after them, but unwanted pregnancies ruin lives, and an unwanted child faces the ultimate rejection. Until there is a 100-per-cent effective means of contraception, safe and affordable to all, and available to men and women, then I believe termination has to be kept as an option. Also, it would be inhumane and barbaric to force a woman who’d been raped to go through an unwanted pregnancy and to give birth if they didn’t want to. That’s how I feel, at least, although I appreciate others feel differently.

Adrian returned home just before six o’clock and I introduced him to Tilly. I cooked the spaghetti and called everyone to dinner. We’d just sat down when the doorbell rang.

‘I’ll go,’ I said.

Leaving everyone eating, I went to answer the front door. It was Isa, with four large bin liners stuffed full. ‘There’s more in my car,’ she said.

‘Really? I didn’t think Tilly had asked for that much.’

‘She didn’t. Her stepfather was there and had packed the lot. He’s a nasty piece of work, and angry she’s gone.’

‘He sounds very controlling,’ I said, lowering my voice. ‘Tilly has been telling me things.’

‘Yes, she’s told me a few things too. Where is she now?’

‘Having some dinner.’

‘Leave her to eat until we’ve finished unloading, then I’ll have a chat with her. She’s better off away from him. Her mother was in tears, but don’t tell Tilly that.’

I took my coat from the hall stand, then went out into the cold dark night to Isa’s car. We began unloading the bin liners and stacking them in the hall and front room. Her car was full. Once we’d finished, I counted thirteen in all, each one filled to bursting. I guessed this was most, if not all, of Tilly’s belongings. Her stepfather was giving her a clear message: You’re gone for good. There is no coming back. You’re not welcome here any more.

As I shut the front door Tilly came into the hall and stared at all the bags. ‘Are they all mine?’ she asked, clearly shocked.

‘Yes,’ Isa said. ‘I need to have a chat with you. Is there somewhere private we can go?’

‘In the living room,’ I said. ‘Where you were this afternoon.’

‘Thank you.’

Tilly and Isa went down the hall into the living room and Isa closed the door behind them. As a foster carer you have to accept that sometimes you are excluded from meetings in your own home. Isa had a right to talk to Tilly in private and she should tell me what I needed to know when they’d finished.

I returned to the kitchen-diner where Adrian, Lucy and Paula had finished eating but were still at the table talking.

‘What’s the matter?’ Lucy asked, worried, aware that Isa hadn’t simply dropped off Tilly’s belongings and the two of them were now in the living room.

‘Her stepfather is being quite nasty,’ I said. ‘Isa’s having a chat with Tilly.’

‘Tilly hates him,’ Lucy said vehemently.

‘Did she tell you that?’ Paula asked.

‘Yes, and she’s angry with her mother for putting up with him and choosing him over her.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘He’s sent most of her belongings. It’s all in the hall and front room. Could someone help me take the bags upstairs? We’ll stack them along the landing so Tilly and I can sort them out slowly in her own time.’

‘Sure,’ Adrian said, and they all stood ready to help.

‘Not you, Lucy, you’re excused,’ I said.

‘Mum, I have to lift toddlers at work who are heavier than a bag of clothes.’

‘Have you pulled a muscle?’ Adrian innocently asked.

‘No, I’m fine,’ Lucy said, while Paula looked at me questioningly.

I avoided her gaze. I hated having secrets in our family – I encourage openness and discussion – but I respected Lucy’s wish not to say anything at present, difficult though it was.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.