Полная версия

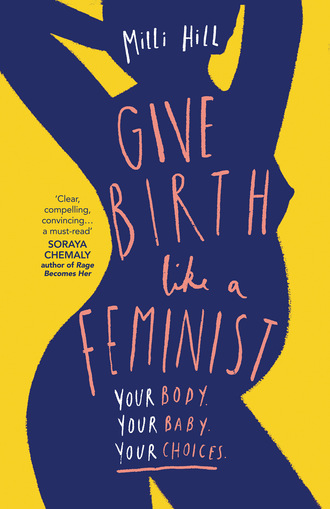

Give Birth Like a Feminist

GIVE BIRTH LIKE A FEMINIST

Your Body. Your Baby. Your Choices.

Milli Hill

Copyright

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ,

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Milli Hill 2019

Milli Hill asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008313104

Ebook Edition © 2019 ISBN: 9780008313111

Version: 2019-07-26

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter 1

‘Am I Allowed?’: The Birth Room Power Imbalance

Chapter 2

Birth: the Land that Feminism Forgot?

Chapter 3

When Women’s Bodies Became Men’s Business: A History of Birth

Chapter 4

Loose Women

Chapter 5

Women’s Bodies: Unfit for Purpose?

Chapter 6

Birth and Culture: ‘Fish can’t see water’

Chapter 7

Birth Rights are Women’s Rights are Human Rights

Stand and Deliver

Resources

Footnotes

Endnotes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Introduction

Birth is a feminist issue. And it’s the feminist issue nobody’s talking about. This book aims to start that conversation.

As I’ve gone through the process of writing this book, I’ve had a few moments where I’ve wondered, why me? My inner critic (don’t try to tell me you haven’t got one of those) has said to me, ‘Milli? Do you really want to open this particular can of worms? As if talking about childbirth wasn’t treacherous enough, now you want to drop the F-bomb?! Are you nuts? That is literally the worst combination of topics. You are going to get burned at the stake – well, metaphorically speaking, at least.’ My inner critic is such a gas.

It’s true, it’s not always easy to talk about childbirth, and it’s not always easy to raise feminist issues. People can even argue about what feminism actually is, but to me it’s simple: feminism just means noticing when women are getting a raw deal, and taking action. And this is where the problem lies with childbirth. Not enough people are noticing that women are getting a raw deal, and not enough people are taking action. We’ve become blinkered to the massive imbalance of power in the birth room, and somehow come to accept that birth is inherently unpleasant and undignified, or even traumatic, degrading and violating. ‘That’s just how it is!’ Well I want this book to tell you it doesn’t have to be that way, and as feminists we must no longer tolerate this state of affairs.

Feminism doesn’t have to be complicated, and it doesn’t have to be exclusive. Giving birth like a feminist doesn’t mean giving birth a certain way, just as doing anything else – career, relationships, parenting – ‘like a feminist’ doesn’t require a one-size-fits-all approach. You can give birth like a feminist in any setting and in any way, from elective caesarean in a private hospital to freebirth in the ocean. All that’s required is that you have somehow moved from a passive place where you view birth as something that happens to you and over which you have no control, to a place of understanding that you may get a raw deal in this experience if you don’t wake up and get yourself into the driving seat. Essentially: take charge, take control, and make conscious choices.

When I speak at mainstream maternity events, I am often shocked by the fact that telling women and their partners that they have rights and choices in the birth room so often seems to come as a revelation. Many people have no sense of themselves as autonomous or powerful in their labour and birth, nor do they feel that there is anything they can do or not do to influence the way their birth unfolds. They are often misinformed and, to compound this, their belief that they have little or no agency then prevents them from seeking out much information. What is the point in learning about your options against a backdrop in which the phrase ‘not allowed’ is used with such alarming frequency? Most pregnant couples believe that the majority of choices are out of their hands. In practical terms this means that, on a daily basis, fingers enter the vaginas of women who do not know they can decline. How can this be acceptable? Even the most progressive of maternity conversations emphasises ‘informed consent’, with the unspoken assumption that consent, not ‘decision making’, or possibly even ‘informed refusal’, is the goal. Maternity professionals will speak of how they ‘consent’ women – using it as a verb, ‘I am just going to go and consent her’, as if the professional is the active one in the exchange and the women herself is passive. It’s time to challenge a system that perpetuates this myth of unquestioning co-operation and female powerlessness.

When you raise a complaint about a female experience, you quite often get quickly reminded of how unusual, niche or rare the problem is, and just how good so many women have it. This focus-shifting is epitomised so well by the hashtag #notallmen – used to remind women just how many good, well-rounded men there are in the world when they try to highlight any issue from mansplaining to rape. ‘#notallmen are rapists. #notallmen have sexist attitudes. #notallmen beat their wives, remember!’ Hang on, the women say, we don’t want to talk about the large percentage of wonderful men who respect women – we want to talk about the other bunch, who don’t. But in the diversion, the point has already been diluted, making the aggressor seem like the victim in the process. This diversionary tactic happens in conversations about birth, too. Attempts to complain about anything from lack of consent, to women not being properly listened to in labour, to institutionalised misogyny and racism in maternity care, are so often met with protests from health workers of ‘It’s not like that where I work!’ or ‘Not all midwives/obstetricians are like that, it’s important not to make sweeping statements’, etc. So, before we get started on our journey through this book, I want to stress that my focus throughout is not on individuals, but on the systems in which they operate. Maternity care is a system that needs to be challenged, built by and within another system that needs to be challenged – patriarchy. Please don’t divert attention from this vital issue if you feel that you personally are working in a way that fully respects women as autonomous, or if you received gold-standard care in your own pregnancy. This is indeed wonderful, but it’s not really what we are all here to talk about.

Likewise, there can sometimes be protests that we should be doing more to celebrate the wonderful men – and in the same way the wonderful maternity care providers – who are ‘getting it right’. It’s true, there are some brilliant midwives, doctors, obstetric units and organisations out there who are providing the most fantastic, refreshing, woman-centred, personalised maternity care – and yes, praise is a good thing, and yes, some of them are in this book. But do we really need to repeatedly celebrate those who are simply providing what women need and deserve? Do men who treat women with respect need a great big pat on the back? No – they are simply behaving normally, with the required, standard levels of kindness and compassion. There should not have to be medals for this, and for the same reasons I have not devoted endless pages of this book to good, decent, rights-based maternity care. Listening to women, caring for them as individuals, and respecting them as the key decision maker in the birth room should cease to be seen as a shining beacon in the darkness and start to be viewed as the baseline norm.

Currently, we are not getting birth right. This matters primarily because birth is a key human experience that will be remembered in great detail by a woman, and her partner, for the rest of their lives. In this book I have tried to ask some difficult questions about the kind of births women are currently experiencing vs. the kind of births that may be possible or desired. These are not easy conversations to have, not least because all women are different and will want and prioritise different things. Added to this, there is a weight of emotion brought to the discussion by those women who have already given birth and had traumatic or disempowering experiences. In spite of the complexity of the topic and the difficult feelings that discussing it evokes, I sincerely hope that this book will pull women together to work on this problem by truly listening to each other and in the true feminist spirit of solidarity. We owe it to those who are yet to give birth to ensure that we all collectively approve of the direction that the birth experience is taking.

Intervention rates in childbirth are rising rapidly, and we should all be concerned about this. This is not just my personal viewpoint. Leading bodies such as the World Health Organisation have expressed concern that the medicalisation of childbirth, with its focus on how to monitor, measure and control birth, has left the question of how women actually feel about their births completely off the agenda, potentially robbing them of a life-enhancing experience.[1] The world’s most prestigious medical journal, The Lancet, has drawn attention to the ‘too much too soon’ approach to birth, most often found in high-income countries, in which treatments that were originally designed to manage complications are now overused, missing an opportunity for women to feel strong and capable.[2] You will notice that in this book I have given plenty of attention to the issues around ‘natural’ or ‘physiological’ birth, because I do feel that this is a key topic for feminist focus. In writing about natural birth, I have often had the sense that I am ‘championing the underdog’. Because we have to accept that, currently, natural birth – in which a woman has a baby without any pharmacological input such as induction, augmentation or drugs to expel the placenta – is very rare. Rarer still are what I call ‘hands-off’ births, in which women, rather than being ‘managed’, rely on their own instinct, follow their body’s lead, and are not guided into certain positions or told when and how to push. Women who have their baby in this way, feeling totally confident in the loving support (and, if necessary, medical help) that they know is in place in the background, but left to give birth entirely under their own steam, will most often talk of the experience in evangelical terms, as life-changing moments in which they felt sexual, sensual, strong, vital and powerful. You can’t help but wonder when you hear their stories how much the world might change if more women were getting this transformative power boost as they crossed the threshold to motherhood. Instead, it’s becoming much more ‘normal’ to have a birth in which you feel unsupported, disempowered and traumatised. I therefore feel it’s vital that we have a conversation about the value to women of this type of ‘straightforward’, ‘physiological’ or ‘natural’ type of birth experience, which is currently on the brink of extinction.

We also need to talk about those women who don’t want or cannot have straightforward vaginal births. There is literally not one single birth scenario in which increasing empathy for the woman, listening to her voice, respecting her decisions, and honouring that this is an extraordinary day in her life will not be valid. There is literally not one single type of birth that we cannot improve upon. The best way to find out more about this is again to listen to women. I learned so much about what women want in birth from talking to those who have experienced caesarean, and in particular, caesarean under general anaesthetic – often the most difficult birth experience to process and recover from. From them I learned that the smallest of gestures can make the biggest and most life-changing differences. Taking a few moments to photograph the newborn on their mother’s chest, for example, even if she is still unconscious, will create something she will treasure for a lifetime, a tangible antidote to her trauma. Women repeat again and again how much it means to them to know that their hands were among the first to touch their baby, even if they were not ‘there’ to experience it. Every small gesture matters, and we can always do better.

Two radical ideas underpin this book. Firstly, birth is a really important experience in a woman’s life and it’s time to stop telling women that it’s ‘just one day’ in which they ‘leave their dignity at the door’ because a ‘healthy baby is all that matters’. These are old-fashioned ideas, riddled with disrespect for women, for their autonomy, and for their feelings as sentient humans, that have no place in the twenty-first century. This book will try to unpick these ideas by looking at some of the history of birth, at various feminist perspectives, at the links between birth, female sexuality and power, and at the current culture of fear and disempowerment that continues to prop up these faded ideologies. Simultaneously, the book will try to replace these outdated perspectives with new considerations of women’s rights in childbirth, their bodily integrity, in particular through the lens of #metoo, and take a fresh look at what we might find, both literally and figuratively, in a birth room built with women’s needs in mind.

The second radical suggestion that this book will make is that pregnant women should be elevated to the role of key decision maker and most powerful person in the birth room. I can tell you from a decade of talking to women about their maternity care that, while there may be frequent reassurances that this is already the case, in reality it tends to make people uneasy. We see this most clearly when women try to go against the flow, birth outside of guidelines or refuse to consent to or accept the standard protocol or approach. These women, and often too, the midwives or doulas who support their choice ‘no matter what’, will often meet huge resistance, and risk sanctions or even punishment, as we will see in several stories in this book. We need a shift in consciousness, that moves to trusting women to make the right choices for themselves and for their baby. We need an acceptance that the image of a wayward, misinformed, irresponsible or even ‘mad’ woman, who does not have the best interests of her baby at heart, is a damaging and misogynist stereotype, used to justify the control of women, and rarely to be found in reality. In this book you will find several references to ‘freebirth’ – where women choose not to have any medical professionals attend them but simply give birth by themselves. I have to be honest with you and say that I personally would never choose to birth without medical back-up. However, I totally and utterly support another woman’s decision to make this choice. Do you? Because I believe that the key to birth freedom, for all of us, lies in supporting women in choices that we would not make ourselves, or even choices that we just feel are plain ‘wrong’. We need to trust women. Ironically, if we manage to move to this place, we may suddenly find that the numbers of women who wish to freebirth or birth outside the system, begins to decline. Increasing numbers of women, quite understandably, don’t want to birth in a system that doesn’t listen to them, respect them or trust them.

Whether you are reading this book as a pregnant woman, a health care provider, or just as a person who cares about women’s issues, I hope it switches on a light for you. First and foremost I hope that birth is suddenly illuminated as a feminist issue for you in a way that, perhaps, it never has been before. I hope it gets you thinking about the ways in which birth matters, about women’s power, agency and autonomy in birth and about what we could be doing differently or better. I hope you are excited or inspired by some of the things you read in these pages and, equally, I am sure that there will be parts that you fervently disagree with, that are hard to hear, or that even make you angry. That’s OK. As I keep telling my adorable inner critic, there will be many different reactions to this book, but ultimately all of them, ‘good’ and ‘bad’, will be much-needed voices, adding to the dialogue about birth as a feminist issue and moving it forwards. And this is essential if we wish to create a future in which women get the positive experiences of birth that they so desperately want, the medical help they truly need, and the power, respect and autonomy they so absolutely deserve. Let’s start the conversation.

Chapter 1

‘Am I Allowed?’: The Birth Room Power Imbalance

The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don’t have any.

Alice Walker[1]

The year is 1975. A woman in a hospital nightgown, shaky on her feet, is wandering the corridor outside the labour ward, using the wall to support her. It’s 3 a.m. She is looking for something she has lost: her baby.

On the previous day several things happened to her that were ‘routine’. When I say ‘routine’, what I really mean is that nobody asked her permission. She was induced because she was past her due date. Her pubic hair was shaved off. She was given an enema. The opioid pethidine was injected into her thigh shortly before delivery. And her perfectly healthy baby was given to her and her husband to hold for a while, before being taken off to the hospital nursery for the night. She did not actively consent to any of this. It was just ‘how it was done’.

Ushered back to bed by the stern but kindly matron, my mother never questioned her experiences of birth until, several decades later, she began to hear a new narrative from the baby they had taken to the nursery – me. In the midst of my own pregnancy journeys, I started to ask questions. ‘How far past your due date were you?’ ‘Why did they shave women – was there any evidence to support this practice?’ ‘Did you ask for the pethidine?’, ‘Did they give me formula in the nursery?’

‘I don’t know. You didn’t really ask questions then.’

‘Why didn’t you just tell them you wanted to keep your baby with you?’

‘Well … they just didn’t let you do that I suppose. It just wasn’t allowed.’

‘They did not let me’, ‘I was not allowed’ … you would think these two phrases would be confined to the history books. And yet thirty-two years later, they were to become part of the fabric of my own first daughter’s birth story, when I was ‘not allowed’ a home birth but instead ‘had to’ be induced because I was past my expected due date, and then ‘had to’ have a forceps delivery, because current policy ‘did not let me’ spend longer than two hours in the pushing stage. There were countless other small incidents during my pregnancy, labour and birth in which what was about to happen to me was presented as ‘policy’ or ‘procedure’. The professionals I met were kind and caring, but I did not feel like I had been given a choice.

As a new mother, I contemplated all of this as I sat on my stitches and nursed my newborn in the long, isolated hours so typical of modern motherhood. I wondered – as an educated woman with a reputation for being ‘opinionated’, ‘persistent’, even ‘nasty’ (depending on the viewpoint of the observer) – how had this happened to me? I had laboured, as I had wanted to, free and naked, in a nest of blankets and cushions on the hospital floor. I had groaned and chanted, unfettered by drugs. I had gone to the abyss and fought my demons, as many labouring women need to do. And as I lay on that floor I had connected with my inner wild woman, with my maternal lineage, and with all the women who had been on this epic journey to meet their babies before me.

But somehow, I had been woken from this deep, almost hallucinatory trance, and moved from this place. A man had come and told me my time was up. I had been taken to the bed. I had been made to put on a shirt and cover my breasts. My feet had been placed in stirrups. I had said no to all this, but I had been told I ‘must’.

At the moment of birth, I called out, in almost sexual tones, ‘Oh, yes!’, as my daughter’s body finally slipped free. It’s true, it did feel like the most perfect, ecstatic release, but the way I vocalised it was quite conscious and deliberate. It was a clear message. I wanted the doctor to know that he had not taken this pleasure from me. I had been sanitised, covered up, conventionalised, conformed: this declaration of pleasure was my final act of rebellion.

The memory of this rather strangely timed two-finger salute to my obstetrician is evidence to me, as I look back on that day just over a decade later, that even in that moment, I already knew I’d been hoodwinked. Even though I had gone into the hospital with an academic understanding of many of the feminist issues that surround modern birth, and with the desire to avoid unnecessary intervention, I had somehow ended up with my feet in stirrups. It almost felt like I had become a living metaphor: the wild woman tamed, the naked woman clothed, the renegade woman cut, the mad woman put firmly back in the attic. No wonder I made that final rebel yell.

The Language of Permission

In the months and years that followed I began to listen to other women’s birth stories with a keen ear, waiting to hear for the tipping point where they had either triumphed or, as I had, slipped beneath the waves. In every story from across the Western world I heard the same words over and over: ‘They did not let me’, and ‘I was not allowed’. I heard it so much so that I gave this phenomenon its own special name, ‘The Language of Permission’.

‘I had to have a vaginal exam, as soon as I arrived at the hospital, to check if I was in labour.’

‘I wanted to have a water birth, but I was not allowed to use the birth centre[fn1] because of my BMI, so I had to be on labour ward.’

‘Because I was trying for a VBAC,[fn2] I was not allowed to eat or drink in labour, in case I ended up having another caesarean.’

‘My partner wanted to come with me for that part, but he was not allowed.’

‘They don’t let you have skin to skin with your baby after a caesarean in my hospital.’

‘They told me not to push yet even though I was desperate to.’

… and so it went on.

I began to wonder how these phrases were tripping so readily off our tongues as women of the twenty-first century. We would not accept being restricted in this way in our relationships or marriages, in our educational choices, or in our career paths. Why, when it came to giving birth – arguably a pretty significant moment in a woman’s life – were we using such passive language, casting ourselves as the ‘permission seekers’, rather than the ‘permission givers’?