Полная версия

Falling Upwards

The idea of the men being thrust into or entombed in ‘an immense block of black marble’, and held there forever in its ‘cold and dark embrace’, is strangely unsettling. Is it a shivering anticipation of the Victorian horror of being buried alive; or even of some nightmare of sexual entrapment? The passage is curiously reminiscent of some of the later horror stories of Edgar Allan Poe, such as ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’. In fact it is highly likely that Poe read this very description as soon as it was published, for it turns out that he was following the accounts of Green’s balloon adventures very closely from the other side of the Atlantic.

4

The year before Green’s epic flight, Edgar Allan Poe had written one of the earliest of his fantasy stories, ‘The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall’, published in the mass-circulation newspaper the New York Sun in June 1835. It is a highly technical and perversely well-imagined account of a successful ascent to the moon – in a home-made balloon of ‘extraordinary dimensions’, containing forty thousand cubic feet of gas.21

Pfaall’s lengthy preparations are given in great detail, his equipment including a specialised telescope, barometer, thermometer, speaking trumpet, ‘etc etc etc’, but also a bell, a stick of sealing wax, tins of pemmican, ‘a pair of pigeons and a cat’. Immediately upon launching, an explosion leaves him hanging upside down from a rope beneath the balloon basket. This proves to be a typically Poe-like state of horrific suspension (‘I wondered … at the horrible blackness of my finger-nails’) which would often be repeated in later stories.

Ingeniously recovering himself by hooking his belt buckle to the rim of the basket, Hans describes how his balloon, ascending ‘with a velocity prodigiously accelerating’, rapidly overtakes the record height achieved by ‘Messieurs Gay-Lussac and Biot’. He soon crosses ‘the definite limit to the atmosphere’. On the way he has another Poe-like vision into the centre of a stormcloud: ‘My hair stood on end, while I gazed afar down within the yawning abysses, letting imagination descend and stalk about in the strange vaulted halls, and ruddy gulfs, and red ghastly chasms of hideous and unfathomable fire.’

Hans succeeds in breaking out of the earth’s gravitational field, and uses a patent ‘air-condenser’ to breathe. But his ears ache and his nose bleeds. During nineteen days and nights, he observes the steadily retreating surface of the planet, gradually reduced to a curving globe of gleaming blue oceans and white polar ice caps: ‘The view of the earth, at this period of my ascension, was beautiful indeed … a boundless sheet of unruffled ocean … the entire Atlantic coasts of France and Spain … of individual edifices not a trace could be discovered, the proudest cities of mankind had utterly faded away from the face of the earth …’

He eventually floats upwards into the moon’s gravitational sphere, and begins to drift into lunar orbit. At this point the balloon turns round and begins a rapid descent towards the lunar surface. After landing, the balloonist is surrounded by an aggressive mob of small, ugly-looking creatures, ‘grinning in a ludicrous manner, and eyeing me and my balloon askance, with their arms set akimbo’.

After desultory greetings and unsatisfactory conversations, Hans turns from them ‘in contempt’, and lifts his eyes longingly above the lunar horizon. The version of ‘earthrise’ which follows is one of the most hauntingly poetic passages in the entire story. ‘Gazing upwards at the earth so lately left, and left perhaps forever, [Hans] beheld it like a huge, dull, copper shield, about two degrees in diameter, fixed immovably in the heavens overhead, and tipped on one of its edges with a crescent border of the most brilliant gold.’

Poe’s final, delicate irony is that the moon creatures do not believe the earth is inhabited. They think Hans Pfaall is a great and inveterate liar. And when, after a five-year lunar sojourn, he somehow contrives to get a message taken back across space by ‘an inhabitant of the Moon’ to the earth, addressed to the ‘States’ College of Astronomers in the city of Rotterdam’, they in turn dismiss Hans as a ‘drunken villain’, and his missive as ‘a hoax’. Poe’s readers are sardonically asked to draw their own conclusions.

Within less than a decade, Poe would return to the subject of balloons and amazing flights. This first pioneering tale, written when he was only twenty-six, is evidently inspired by Cyrano de Bergerac’s Histoire comique. But its technical originality and brilliance, its mixture of scientific realism and metaphysical terrors, suggests the wholly new dimension of science fiction.22

5

Perhaps to counter just such metaphysical terrors, somewhere towards 1 a.m. Green allowed the balloon to sink until the long trail rope, though invisible, was again reassuringly in touch with the ground. They minimised the flame of their overhead safety lamp, and gradually ‘the intensity of the darkness yielded’ and they could pick out very faint shapes below – vast, shadowy stretches of forest looming out against snow, and the dull gleaming curve of an enormous river which they calculated must be the Rhine. These shapes were an extraordinary relief, familiar forms which, as Mason wrote, ‘acknowledged the laws of the material world’.23

Yet flying so close to the earth in what was evidently a landscape of steeply wooded valleys was a risk, and they had frequent moments of alarm. On one occasion around 3 a.m. a thin, luminous shape, like a watchtower or a spire, suddenly seemed to be approaching them at terrifying speed and at exactly their height. For several agonising moments all three leaned out of the basket, desperately trying to see what the obstacle was, and how they could possibly avoid it. Finally Green realised that it was a section of their own stay rope, hanging down from the crown of the balloon, not more than twenty-five feet outside the basket. But, caught by the reduced light from their low-burning lamp, it gave the alarming illusion of a distant object hovering directly in their path. Once again the night had deceived them.24

The night had also become increasingly cold, and their thermometer now dropped well below freezing. Even the coffee – deprived of its lime heater – was frozen solid in its canister. They held it just above the lamp to thaw it back into liquid form. The crew were tense, and morale was a little low. They drank brandy and talked of the great polar navigator Captain William Parry, and his heroic attempts to discover the North-West Passage through the frozen wastes of the Arctic Circle, and to reach the North Pole (as it turned out, a prophetic conversation).25

At 3.30 a.m. Green decided to climb back up to a safer height, and look for the first welcome indications of dawn. He discharged a little ballast, but to his surprise the balloon seemed to gather momentum as it climbed, and very shortly their barometer indicated a height of twelve thousand feet, far higher than he had intended, more than two miles up. Once again they were surrounded by total enveloping blackness and complete silence, except now there were a few scattered stars high above. As they were gazing up at these, something really terrifying happened. There was a sharp cracking sound from the balloon canopy overhead, a sudden jerk on the hoop, and then the whole basket began to drop away beneath their feet.26

Mason vividly described his sensations of horror. His narrative suddenly leaps into the present tense:

At this moment, while all around is impenetrable darkness and stillness most profound, an unusual explosion issues from the machine above, followed instantaneously by a violent rustling of the silk, and all the signs which may be supposed to accompany the bursting of a balloon … In an instant the car, as if suddenly detached from its hold, becomes subjected to a violent concussion, and appears at once to be in the act of sinking with all its contents into the dark abyss below. A second and a third explosion follow in quick succession … 27

Rigid with terror, clinging to the basket’s edge, Mason knew that nothing could now avert his death. Then, with equal suddenness, everything about the balloon reverted to normal. The basket became steady, the balloon canopy smooth and silent above them; all was just as tranquil and reassuring as before. Mason stood gazing blankly at Hollond, both men still clinging to the edge of the basket, pale with shock.

Green reassured his shaken passengers about what had happened. It was all quite normal, he told them with a smile, and could be explained by simple physics. While they had been flying near the ground and in increasingly cold air, the canopy of the balloon had gradually shrunk and folded in on itself, as its volume of hydrogen contracted. But as it was night, no one (except Green) had observed this. Then during their rapid ascent the balloon entered regions of lower pressure, and the hydrogen rapidly expanded again. This forced the canopy to reinflate more swiftly than usual. The loose folds of silk, concertina-ed or ‘corrugated’ together, and partially stuck by ice, did not immediately open. Only when sufficient hydrogen pressure had built up to snap them forcefully apart did the balloon resume its full shape in a series of sharp, violent unfolding movements.

Moreover, chuckled Green, the terrifying jerks on the hoop were actually the basket being pulled upwards as the balloon expanded. The sensation of falling was strictly speaking an illusion: they were actually ‘springing up’ rather than dropping down. All was well. But perhaps they should all have some more brandy?

How far this account reassured his passengers is not clear; nor even how far Green himself had been taken by surprise. It must have occurred to him that the unexpected rapidity of their ascent was in fact extremely perilous, as one of the frozen folds of silk could easily have ruptured before it was forced apart by the pressure of the hydrogen. He later emphasised to Mason that he had ‘frequently experienced the like effects from a rapid ascent’.28

Altogether it was a huge relief when the November dawn slowly began to lighten the sky. The ground below seemed strangely smooth and luminous, and they gradually realised that they were again passing over ‘large tracts of snow’. The bitter cold had increased: they could see the plumes of their own breath, and the glistening ice that had formed on the lower canopy of the balloon. The question of their exact location now became pressing. According to their compass they had been travelling steadily due east for most of the night. Green made a quick dead-reckoning calculation, and concluded that, based on the speed with which they had reached Liège, it was possible they had travelled up to two thousand miles from England. This would put them somewhere over ‘the boundless planes of Poland, or the barren and inhospitable Steppes of Russia’, an alarming prospect. In fact, as Mason later admitted, this was an unduly ‘extravagant’ estimate, over 110mph, largely inspired by the long period of darkness, disorientation and terror they had experienced.29 When they eventually landed at 7.30 a.m., descending inelegantly into a stand of snow-covered fir trees (their sand ballast had frozen solid and could not be properly released), they found that they were still in north Germany. Local foresters, tactfully recruited by means of the balloon’s copious stores of brandy, led them in triumph to the little country town of Weilburg. They were thirty miles north-west of Frankfurt, in the Duchy of Nassau.

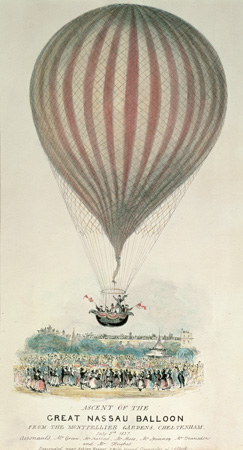

Yet their achievement was spectacular. They had travelled 480 miles in eighteen hours.30 This was a long-distance record for a balloon flight, at an average speed of just over twenty-six miles per hour, roughly the same rate as when they set out. But they had covered an astonishing eastwards trajectory, on a line that ran roughly through Calais and Brussels, to Liège, Coblenz, and almost as far as Frankfurt. The Vauxhall had survived in good order, and was immediately rechristened the Royal Nassau, after their landing site. News of the flight caused an international sensation. On the way back Green spent some time in France, and flew his famous balloon from several sites around Paris and at Montpellier Spa. His international reputation was made.

6

The flight inspired something like a renewed balloon craze. Crowds of tourists and foreign visitors flocked to the Vauxhall Gardens. Numerous articles, editorials and poems were published in the press. The fashionable painter John Hollins produced a striking composite portrait entitled A Consultation Prior to the Aerial Voyage to Weilburgh, which is now in the National Portrait Gallery. The balloonists and their financial backers (including Hollins himself) are shown gallantly grouped around a large planning table, with maps and sheets of calculations, like generals working out a military campaign. Green, seated at the right, gazes purposefully across the table at Robert Hollond MP, seated on the left, while Monck Mason, their historian, stands between them apparently lost in thought. The Royal Vauxhall – now the Royal Nassau – can be seen outside through a window, tethered like an impatient warhorse.

If the flight was heroic, it also had – like all balloon flights – its comic aspects. It had flown over several countries; but mostly at night, when nothing could really be seen. It had achieved a distance record, certainly; but without the balloon ever being capable of steering towards any destination. It had revolutionised long-distance travel, but without making it any more practical. Thomas Hood, famous for his Chartist ballad of the working man, ‘The Song of the Shirt’, wrote several humorous poems in praise of ballooning, including ‘The Flying Visit’. But he outdid himself with a bubbling, mock-heroic party piece, ‘Ode to Messrs Green, Hollond and Monck on their late Balloon Adventure’. It opens with a high, jocular, punning invocation in a ‘champagne style’ that he had invented especially for the occasion:

O lofty-minded men!

Almost beyond the pitch of my goose pen

And most inflated words!

Delicate Ariels! Etherials! Birds

Of passage! Fliers! Angels without wings!

Fortunate rivals of Icarian darings!

Kites without strings! … 31

Hood, with his gaseous puns and mocking emphasis on the amount of food and drink consumed by the aeronauts under the stars, tended to treat the whole expedition as an enormous prank. But Monck Mason was serious. After publishing several articles, his carefully completed account of the voyage appeared two years later in book form as Aeronautica (1838). He made the story especially memorable by his haunting description of night flying.

Mason later added a hundred-page appendix on the general experience of flying in balloons: the euphoric sensations of ascent, the diminution of the people below, views of clouds and sunlight, the spherical appearance of the earth beneath, and the particular panoramic and sharply ‘resolved’ view of cities, rivers, railways. He is surprisingly perceptive about the strangely ‘delineated’ sounds heard from below, and the way they create an entire sound ‘landscape’: the rural world of farm dogs, cattle, sheep-bells; but also sawing, hammering and agricultural flails; sportsmen’s guns or the ‘re-iterated percussion’ of mill wheels.

Some of this is weakened by Mason’s orotund pseudo-sublime manner, by which he attempts to give ballooning a kind of contemplative gravity, the exact opposite of Hood’s mad ‘levity’. But there are many fine existential passages: on the sense of extreme solitude and silence in ‘the immense vacuity’; on the sublime appearance of cloudscapes and the ‘Prussian blue’ zenith at high altitudes; and on the uneasy feeling of ‘intruding’ on God’s territory, ‘the especial domains of the Almighty’.32 Above all, he attempts to evoke the strange and beautiful other world of the kingdom of the air:

Above and all around him extends a firmament dyed in purple of the intensest hue, and from the apparent regularity of the horizontal plane on which its rests, bearing the resemblance of a large inverted bowl of dark blue porcelain, standing upon a rich mosaic floor or tessellated pavement. In the zenith of this mighty hemisphere – floating in solitary magnificence – unconnected with the material world by any visible tie – alone – and to all appearances motionless, hangs the buoyant mass by which he is upheld … 33

Throughout such passages there is a curious mixture of scientific terminology – horizontal plane, zenith, buoyant mass – with the rhetoric of Victorian poetry and sublimity; even on occasion of Victorian prayers or hymns. This seems to reflect a philosophical, or even theological, problem later expressed by many Victorian balloonists. To what extent is the upper sky, where Prussian blue deepens into black, ‘the space beyond the limits of our atmosphere’,34 a scientific zone or a celestial one, or both? What unknown powers or energies lurk in the terrific ‘black and fathomless abyss’ – an abyss paradoxically overhead? What monsters or deities does the upper deep contain?fn14

To give his book further weight, Mason added six other appendices to later additions. Appendix B consisted of a short biography of Charles Green, with accounts of an earlier test flight made with Green from Vauxhall to Chelmsford on 4 October 1836, and of Green’s part in the fatal Cocking parachute experiment of 1838, in which the over-confident inventor Robert Cocking leapt to his untimely death above the Thames Estuary, and almost killed his pilot Green into the bargain. Appendix C was an alphabetical checklist of all known European aeronauts between 1783 and 1836, with longer individual notes on the early pioneering figures like Blanchard, Lunardi, Sadler, Gay-Lussac and Garnerin. Appendix D, ‘On the Mechanical Direction of the Balloon’, investigated the old question of navigating a balloon. Appendix E considered Green’s use of the guide rope and other ‘equilibrium’ devices. Appendix F reflected on the limitations of bird flight (but with special praise for the gliding capacities of the South American condor ‘above the lofty peaks of the Andes’). And Appendix G indulgently reprinted further verses in praise of the Nassau flight.

Thanks to Green, ballooning had once again caught the imagination of writers, but its significance was interpreted in increasingly various ways. In 1837 Thomas Carlyle used the image of balloons in his introductory chapter, ‘The Paper Age’, in The French Revolution, to express the political risks and hopes of the time: ‘Beautiful invention, mounting heavenward – so beautifully, so unguidably! Emblem of our Age, of Hope itself.’

In 1838 John Poole (who had once seen Sophie Blanchard fall to her death in Paris) gave a more satirical but shrewdly perceptive account of a flight with Green at night over the East End of London. It seems to him very different from Paris, with its boulevards, parks and cafés. The sinister, garish lights of gin ‘palaces’, taverns, apothecaries and brothels – alternately twinkling ‘blue, green, purple and crimson’ – are used to explore the notion of the hidden city of poverty, sickness and crime. On landing near Hackney Marshes, the balloon is surrounded by a threatening mob, which has pursued it all the way ‘from Stepney, Limehouse and Poplar’. Prophetically, it was as if the balloon had trespassed into an African jungle, and stirred up an unfriendly horde of howling ‘natives’. Assaulted by ‘their yells, their savage imprecations, curses both loud and deep, their threats to destroy the balloon’, Poole, Green and his burly crew just manage to pack their equipment onto a cart, and beat a strategic retreat to the local Eagle and Child public house. Here they hole up until one in the morning, when it is safe to slip back through the silent streets to the West End and ‘civilization’.36

In his poem ‘Locksley Hall’ (1842), with its own visions of social disturbance and upheaval, the thirty-three-year-old Alfred Tennyson imagined the aeronauts not merely as romantic adventurers, but also as busy commercial traders. They descend in flocks through the evening skies, to settle upon distant marketplaces around the globe. They are part Homeric travellers in the tradition of Jason and the Argonauts; but also partly hungry commercial travellers, with just a hint of a cloud of locusts descending upon an innocent land at dusk:

For I dipt into the future, far as human eye could see,

Saw the Vision of the world, and all the wonders that would be;

Saw the heavens fill with commerce, argosies of magic sails,

Pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales …

The poem was originally drafted in 1835. But Tennyson also foresaw, like Franklin before him and H.G. Wells afterwards, balloons producing the terror of aerial warfare:

Heard the heavens fill with shouting, and there rained a ghastly dew

From the nation’s aerial navies, grappling in the central blue. 37

Charles Green had established himself as much more than a balloon showman, or the publicity agent of the Vauxhall Gardens. He had resurrected the old dream of ballooning, but adapted it to the coming Victorian age. Bronze medals were even cast in his honour.

In his Preface to the second edition of Aeronautica, Mason suggested that Green’s ambitions were turning towards an Atlantic crossing. Green apparently took a quite nonchalant view of the huge distances and meteorological challenges this would involve: ‘In his view, the Atlantic is no more than a simple canal: three days might suffice to effect a passage. The very circumference of the globe is not beyond the scope of his expectations: in fifteen days and fifteen nights, transported by the trade winds, he does not despair to accomplish in his progress the great circle of the earth itself. Who can now fix a limit to his career?’38

This was heady talk, and made good journalistic copy. But Mason was not a successful balloon pilot himself, merely a successful balloon passenger, and had perhaps had his head turned by all the excitement and publicity. In the same Preface he cheerfully advocated the use of a trailing guide rope ‘above fifteen thousand feet in length’. He saw no problem in this monster appendage dragging across ‘trees, houses, rivers, mountains, valleys, precipices and plains’ with what he described as ‘equal security and indifference’.39

7

Two years after the publication of Aeronautica, in 1840, Green issued his own proposals to fly the Atlantic. He claimed to have identified a prevailing west-to-east wind current in the upper atmosphere, which meant that he would start the crossing from America. ‘Under whatever circumstances I made my ascent, however contrary the direction of the wind below, I uniformly found that at a certain elevation, varying occasionally but always within 10,000 feet of the earth, a current from west to east, or rather from the north of west, invariably prevailed.’