Полная версия

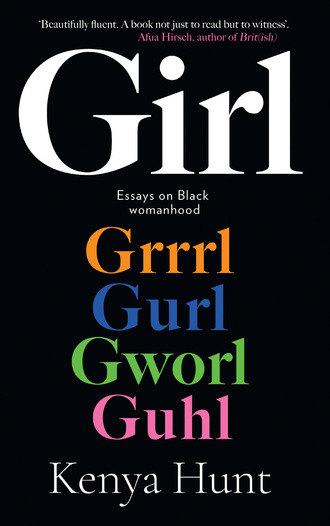

GIRL

My life had changed considerably in the years between the two events. I was no longer a new expat homesick for community, searching for like-minded friends. By that point I had become a part of a large, loosely connected network of Black creatives, many of whom were planning to be at the premiere of Black Panther at the Hammersmith Apollo. And when I arrived at the theatre, I realised I had finally found that sprawling, expansive, loud and proud mass moment of Blackness I had been craving when I first moved to the UK.

Outside, the streets were cold and dark. But inside, the venue was alive, every seat full and the walls vibrating with a mix of loud music and animated voices reverberating throughout the space: speaker-shaking bass, Kendrick Lamar’s flow and high-pitched ‘Ayyyyyeeees!’ The audience doubled as a fashion show — all party dresses and heels, statement jackets and sunglasses, conversation-worthy hair and nails.

I had arrived nearly an hour late to find the movie was nowhere near beginning, despite the 7 p.m. start time listed on the invitation. I fell in line with a string of latecomers, climbing the theatre’s red-carpeted steps behind a boisterous group of fabulous-looking women including the actress and comedian Michaela Coel. From my seat I scanned the audience and could make out the rapper Stormzy and actor John Boyega, as well as a slew of media peers and friends. On stage, stars Lupita Nyong’o and Danai Gurira stunned in beaded dresses.

The opening scene rolled nearly fifty minutes later. The screen went black, white stars gradually appearing to reveal a dark night sky. A young boy’s voice, optimistic and inquisitive: ‘Baba, tell me the story of home.’ A glowing, blue meteorite emerges from the darkness speeding towards the continent of Africa and landing in a field of baobab trees, as the boy’s father explains the history of Wakanda, a technologically advanced African nation, hidden away from white colonialism and powered by the strongest substance in the universe, Vibranium.

Moments later we watch another little boy in Oakland, California playing basketball with his friends unaware that inside his apartment upstairs, his father, an undercover Wakandan agent, is being confronted by his brother, the Black Panther.

Throughout the next two hours and fifteen minutes, the audience whooped and cheered as we watched a film in which Black people are hero and villain, saviour and victim, with complicated paths to getting there. And in between the raucous moments of laughter and applause, we sat in contemplative silence as the film told a story of Africa and Black America, posed questions about Black liberation and Black radicalism and presented the possibilities of gender equity. It was a film for and about Black culture, with a record-breaking $200 million budget.

Few works of pop culture are as widely consumed as the superhero film. Of the twenty-five top-grossing movies of all time, more than half are big-budget, meticulously commercialised blockbuster productions revolving around men with superhuman capabilities. One of the most momentous feats of Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther is that it takes the globally revered medium and bathes it in Black. It was the eighteenth Marvel film, but the first to star a Black superhero and all-Black cast. The first to be set in Africa. The first Black film of any kind with such a massive budget. It was a movie in which women ran the place, with women warriors and matriarchs saving the day. It was nominated for an Academy Award. And it was the highest grossing superhero movie ever made (more than $1.3 billion globally).

It was also a gift to a global community of people of all races still reeling from the election of Donald Trump two years earlier and the rise of populism — and a gift released during America’s Black History Month at that.

Much has been made of all these things. But I was struck most by how the movie shifted the conversation around Blackness away from America (a place that has long dominated the conversation) and became a rousing phenomenon for people of colour everywhere, with social media serving as the Vibranium that powered it.

In the film, residents of Wakanda showed their solidarity by crossing their arms over their heart in salute, a move the director Ryan Coogler styled after, among other things, the Egyptian Pharaohs’ burial pose. Years later, some would interrogate the film’s mash-up of African references and argue it was a form of cultural homogenizing that did more harm than good. But as we sat in the theatre we were all self-declared Wakandans too — immigrants and expats and homegrown Brits with roots that spanned Nigeria, Ghana, Jamaica, America, Senegal, Bermuda, Trinidad, South Africa, and more. One big diasporic tribe.

In an interview on The View, Lupita Nyong’o described it like this: ‘Wakanda is special because it was never colonised, so what we can see there for all of us is a reimagining of what would have been possible had Africa been allowed to realise itself for itself. And that’s a beautiful place.’

Wakanda demonstrated to many of us what we already knew, that #Blackexcellence exists on a global scale, on screen and off.

To be clear, Black culture has always had currency and Black excellence has always existed. One need only scroll through centuries of history to see this. But I’m talking about #Blackexcellence, the social media-driven amplification and celebration of Black culture. I’m talking about the rebirth of the Black Is Beautiful movement of the 1960s — which was itself an advancement of the Negritude movement of the 1930s that been inspired, in part, by the Harlem Renaissance — as an entirely new era that sat at the intersection of ideology, technology and economics.

This directly impacted my working life. In the fashion world, European brands were casting a multitude of Black models of all skin tones to sell their clothing on a scale the world hadn’t seen since the Seventies when designers such as Saint Laurent, Halston and Valentino regularly employed a diverse cast of women of colour ranging from Donyale Luna to Pat Cleveland, Iman and Bethann Hardison.

Meanwhile, fashion magazines began casting Black celebrities as cover stars of big issues in unprecedented numbers, after years of mostly quarantining any woman of colour not named Rihanna or Beyoncé to the smaller ‘low risk’ issues of the year (January, February and August, for example), indicating that publishers finally viewed them as bankable enough to do so. In August 2018, so many magazines featured Black women as their September issue cover stars that it made global headlines and inspired a wave of celebratory memes. The BBC and Sky News called asking me to comment on this new phenomenon. Major media outlets began referring to this shift, as well as any other wave of inclusion in predominantly white spaces, as the Wakanda Effect.

Wakanda became a synonym for Black excellence and represented all of its possibilities, yes. But it also became a qualifier mainstream media used to reduce the idea to a trend, a fleeting ‘moment’ that raised the inevitable question: ‘When will it end?’

To me, the decisions to feature Ruth Negga, Lupita Nyong’o, Tracee Ellis Ross, Beyoncé, Rihanna, Zendaya, Yara Shahidi, Slick Woods and Tiffany Haddish on the covers of magazines ranging from British ELLE, a title I worked for, to Grazia, Harper’s Bazaar and American Vogue seemed like a no-brainer. These are all beautiful and accomplished women with a proven track record of appealing to a mass audience. Women who have the body of work, the major cosmetics contracts, the interest of powerful fashion houses — women who tick all the boxes. It galled me that their accomplishments could be reduced to one superhero film.

The impact of the film’s enormous success could not be denied, but Black Panther was a highlight in a groundswell that had been building for years, rather than the instigator of it. For example, before Black Panther, there was Get Out, which broke records as the highest grossing original debut ever. The actress, director and screenwriter Lena Waithe summed it up well: ‘I think Black people in this industry are making art that is so specific and unique and good that the studio heads have no choice but to throw money at us. They’re saying, “How can we support you and stand next to you?” The tricky part is that they want to be allies and they want to be inclusive, but they also want to make money.’

And like Black Panther, her 2019 film, Queen & Slim, a sumptuous love story and heartbreaking reflection on the politics of Black Lives Matter, written and directed by two Black women, probably wouldn’t have been as successful without a global tribe, connected by social media, supporting it.

I saw the film in a special preview in Shoreditch, hosted by BBC personalities Clara Amfo and Reggie Yates. The theatre was filled with London’s homegrown Black excellence, most of them women including model sisters Adwoa and Kesewa Aboah, photographer Rhea Dillon, designer Irene Agbontaen and more. At the end of the screening, guests, eyes wet with tears, all congregated in the lobby for a group, family reunion-style photo, which made the rounds on Instagram in the following days.

It was a moment, and one that was no longer an anomaly in my life. That’s mostly because I had long bedded into life in London, and connected with the city’s diverse network of Black creatives. What I hadn’t imagined, is that Black creativity on both sides of the Atlantic would be as in demand by the mainstream as it currently is.

When we featured Lena in ELLE magazine several years before, she described it as a new version of the Harlem Renaissance and used the analogy again when talking about Black Panther in an interview with the New York Times. ‘We’re definitely in the middle of a renaissance, make no mistake. In twenty years, people are going to be writing about what you’re writing about. But for me, I want more.’

Who doesn’t? We all want to see more of ourselves in places where we aren’t and deserve to be, whether it be on the walls in a British museum, on a screen in a movie theatre, or in the White House. To find our tribe and rally, arms crossed in salute. Wakanda Forever.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.