Полная версия

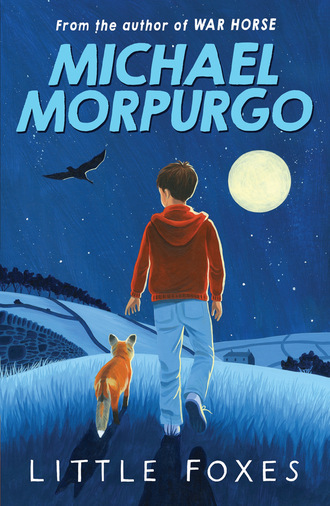

Little Foxes

Also by Michael Morpurgo

Arthur High King of Britain

Escape From Shangri-La

Friend or Foe

From Hereabout Hill

The Ghost of Grania O’Malley

Kensuke’s Kingdom

King of the Cloud Forests

Long Way Home

Mr Nobody’s Eyes

My Friend Walter

The Nine Lives of Montezuma

The Sandman and the Turtles

The Sleeping Sword

Twist of Gold

Waiting for Anya

War Horse

The War of Jenkins’ Ear

The White Horse of Zennor

Why the Whales Came

For younger readers

Animal Tales

Conker

Mairi’s Mermaid

The Marble Crusher

On Angel Wings

The Best Christmas Present in the World

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

CHAPTER ONE

BILLY BUNCH CAME IN A BOX ONE WINTRY night ten years ago. It was a large box with these words stencilled across it: ‘Handle with care. This side up. Perishable.’

For Police Constable William Fazackerly this was a night never to be forgotten. He had pounded the streets all night checking shop doors and windows, but it was too cold a night even for burglars. As he came round the corner and saw the welcome blue light above the door of the Police Station, he was thinking only of the mug of sweet hot tea waiting for him in the canteen. He bounded up the steps two at a time and nearly tripped over the box at the top.

At first it looked like a box of flowers, for a great bunch of carnations – blue from the light above – filled it from end to end. He crouched down and parted the flowers. Billy lay there swathed in blankets up to his chin. A fluffy woollen bonnet covered his head and ears so that all Police Constable Fazackerly could see of him were two wide open eyes and a toothless mouth that smiled cherubically up at him. There was a note attached to the flowers: ‘Please look after him’, it read.

Police Constable Fazackerly sat down beside the box and tickled the child’s voluminous cheeks and the smile broke at once into a giggle so infectious that the young policeman dissolved into a high-pitched chuckle that soon brought the Desk Sergeant and half the night shift out to investigate. The flowers – and they turned white once they were inside – were dropped unceremoniously into Police Constable Fazackerly’s helmet, and the child was borne into the Station by the Desk Sergeant, a most proprietary grin creasing his face. ‘Don’t stand there gawping,’ he said. ‘I want hot water bottles, lots of ’em and quickly. Got to get him warm; and Fazackerly, you phone for the doctor and tell him it’s urgent. Go on, lad, go on.’ And it was the same Desk Sergeant who to his eternal credit named the child, not after himself, but after the young Police Constable who had found him. ‘I’ve named a few waifs and strays in my time,’ he said, ‘and I’ll not condemn any child to carry a name like Fazackerly all his life. But Billy he’ll be – not Billy Carnation, he’d never forgive us – no. Now let me see, how about Billy Bunch for short? How’s that for a name, young feller-me-lad?’ And Billy giggled his approval.

Billy did not know it, but that moment in his box on the table in the Interrogation Room with half a dozen adoring policemen bending over him was to be his last taste of true contentment for a long time. He was not to know it either, but he sent a young policeman home that night to his bed with his heart singing inside him. Billy Bunch was a name he was never to forget.

Billy Bunch was taken away to hospital and processed from there on. First there was the children’s home where he stayed for some months whilst appeals and searches were carried out to see if anyone would claim him. No one did. In all that time he had only one visitor. Once a week on his afternoon off Police Constable William Fazackerly would come and sit by his cradle, but as the months passed the child seemed to recognise him less and less, and would cry now when he reached out to touch him. So, because he felt he was making the child unhappy, he stopped coming.

By his first birthday Billy Bunch had entirely lost the smile he had come with. A grim seriousness overshadowed him and he became pensive and silent, and this did nothing to endear him to the nurses who, try as they did, could find little to love in the child. Neither was he an attractive boy. Once he had lost the chubby charm of his infancy, his ears were seen to stick out more than they should and they could find no parting for his hair which would never lie down.

He did not walk when it was expected of him, for he saw no need to. He remained obstinately impervious to either bribes or threats and was quite content to shuffle around on his bottom for the first two and a half years of his life, one leg curled underneath him acting as his rudder, thumb deep in his mouth and forefinger planted resolutely up his left nostril.

And speech did not come easily to him as it did with other children in the home. Even the few words he spoke refused to leave his mouth without his having to contort his lips and spit them out. This stutter made him all the more reluctant to communicate and he turned to pictures and eventually, when he could read, to books for comfort.

No foster family, it seemed, wanted to keep him for long; and each time his case was packed again to return to the children’s home, it simply confirmed that he was indeed alone and unwanted in this world.

School made it worse if anything. The frequent changes from one foster home to another spoiled any chances he might have had of making firm friends in those early years. And certainly he was not proving to be a favourite with the teachers. He was not bright in the classroom, but most of the teachers could forgive him that. The trouble was that he seemed completely uninterested and made little attempt to disguise it. All he wanted to dowas to read, but he would never read what they wanted him to read.

And with his fellows he was no more popular, for he was neither strong nor agile and had little stomach for competitive games of any kind. At play time he would wander alone, hands deep in his pockets, his brows furrowed. The other children were no more beastly to him than they were to each other, in fact they paid him scant attention. Were it not for his stutter he would have gone through each day at school almost unnoticed.

Mrs Simpson, or Aunty May as she liked to be called, was the latest in the long line of foster mothers. She had thin lips, Billy noticed, that she made up bright scarlet to look like a kiss, and she wore curlers every Sunday night in her fuzzy purple hair. She was a widow with grown-up children who lived away. She kept a clean enough house on the tenth floor of a block of flats that dominated that wind-swept estate on the outskirts of the city. The estate had been built after the War to accommodate the workers needed for the nearby motor factory, and accommodate was all it did. It was tidily organised with rank upon rank of identical box houses, detached and semi-detached, spread out like a giant spider’s web around the central block of flats where Billy now lived. There was little grass to play on and what there was was forbidden to him because he might get muddy, and Aunty May did not like that. ‘After all, you know,’ she was continually reminding him, ‘they only give me so much to keep you each week, Billy, and I can’t be for ever spending on extra washing just because you go out and get yourself in a state. I can’t think why you don’t go and play in the adventure playground with the other children. It’s all concrete there, and much better for you. It’s not fair on me, Billy, not fair at all. I’ve told you before, Billy, if you can’t do as you’re told, you’ll have to go.’

That was always the final threat, and not one to which Billy was usually susceptible, for most of his foster homes had meant little more to him than a roof over his head and three meals a day. Seen like that, one such home was much like any other. But this home was the only one that had ever been special to him. This one he wanted very much to stay in, not on account of Aunty May who nagged him incessantly, and certainly not on account of the school where he lived in dread of the daily torture Mr Brownlow, his frog-eyed teacher, inflicted upon him. ‘Stand up, Billy,’ he would say. ‘Your turn now. Stand up and read out the next page, aloud. And don’t take five minutes about it, lad. Just do it.’ And so he did it, but the inevitable sniggers as he stuttered his waythrough added yet more tissue to the scar of hurt and humiliation he tried so hard to disguise. No, he endured all that and Aunty May only because he had his Wilderness down by the canal to which he could escape and be at last amongst friends.

CHAPTER TWO

THE CHAPEL OF ST CUTHBERT, OR WHAT was left of it, lay in the remotest corner of the estate, a gaunt ancient ruin that was crumbling slowly into oblivion. Like everything else standing on the site it would have been bulldozed when the estate was built, but a preservation order had ensured its survival – no one was quite sure why. So they erected a chain-link fence around the graveyard that surrounded the ruins and put up a warning sign: ‘Keep out. Danger of falling masonry.’ And, for the most part, the children on the estate didkeep out, not because of the sign – few of them knew what masonry was anyway – but rather because it was common knowledge that there were ghosts roaming around the graveyard. And the few who had ventured through the wire and into the Wilderness beyond returned with stories of strange rustlings in the undergrowth, footsteps that followed them relentlessly, and head-high whispering nettles that lashed at intruders as they tried to escape. This was enough to discourage all but the most adventurous children.

Billy was by no means adventurous, but he no longer believed in ghosts and like most children he had always been intrigued by anything that was forbidden. He was on one of his solitary evening wanderings shortly after he came to live with Aunty May when he saw a great white owl fly over his head and into the vaulted ruins. It passed so close to him that he could feel the wind of its wings in his hair. He saw it settle on one of the arched windows high up in the ruins. It was because he wanted a closer look that he pulled up the rusty wire and clambered into the Wilderness.

Since that first evening Billy had returned every day to his Wilderness; skulking along the wire until he was sure no one would see him go in, for the magic of this place would be instantly shattered by any intrusion on his privacy. He would dive under the wire, never forgetting to straighten it up behind him so that no one would ever discover his way in, and would fight his way through the undergrowth of laurels and yew out into the open graveyard. Hidden now from the estate, and with the world wild about him, Billy at last found peace. Here he could lie back on the springy grass the rabbits had cropped short and soft, and watch the larks rising into the sky until they vanished into the sun. Here he could keep a lookout for his owls high in the stone wall of the chapel itself, he could laugh out loud at the sparrows’ noisy warfare, call back at the insistent call of the greenfinch and applaud silently the delicate dance of the wagtails on the gravestones.

In the evenings, if he lay quite still for long enough, the rabbits would emerge tentative from their burrows and sniff for danger, and how his heart leapt with the compliment they paid him by ignoring him. No need ever to bring his books here. It was enough for him to be a part of this paradise. He did not need to know the name of a red admiral butterfly or a green woodpecker in order to enjoy their beauty. He came to know every bird, every creature, that frequented his Wilderness and looked upon them as his own. In spring he took it upon himself to guard the fledglings against the invasion of predatory cats from theestate. A stinging shot from his catapult was usually sufficient to deter them from a return visit. He was lord of his Wilderness, its guardian and its keeper.

Beyond the chapel was the canal. The ruin itself and the graveyard were screened on that side by a jungle of willows and alder trees, and nearer the canal by a bank of hogweed and foxgloves. Hidden here, Billy could watch unobserved as the moorhens and coots jerked their way through the still water, their young scooting after them.

But his greatest joy was the pair of brilliant kingfishers that flashed by so fast and so straight that at first Billy thought he had imagined them. All that summer he watched them come and go. He was there when the two young were learning to fish. He was there when the four of them sat side by side no more than a few feet from him, their blazing orange and blue unreal against the greens and browns of the canal banks. Only the dragonflies and damselflies gave them any competition; but for Billy the kingfishers would always be the jewels of his Wilderness.

One summer’s evening he was kingfisher-watching by the canal when he heard the sound of approaching voices and the bark of a dog on the far side of the canal, and this was why he was lying hidden, face down in the long grass when the cygnet emerged from the bullrushes. She cruised towards him, surveying the world about her with a look of mild interest and some disdain. Every now and then she would browse through the water, lowering her bill so that the water lapped gently over it, then her head would disappear completely until it re-emerged, dripping. Although a dark blue-grey, the bill tinged with green, she looked already a swanin the making. No other bird Billy knew of swam with such easy power. No other bird could curve its neck with such supreme elegance. Billy hardly dared to breathe as the cygnet moved effortlessly towards him. She was only a few feet away now and he could see the black glint of her eye. He was wondering why such a young bird would be on its own and was waiting for the rest of the family to appear when the question was unequivocally answered.

‘That’s one of ’em,’ came a voice from the opposite bank of the canal. ‘You remember? We shelled them four swans, made ’em fly, didn’t we? ’S got to be one of ’em. Let’s see if we can sink him this time. Let’s get him.’ In the bombardment of stones that followed Billy put his hands over his head to protect himself. He heard most of the stones falling in the water but one hit him on the arm and another landed limply on his back. Outrage drove away his fear and he looked up to see five youths hurling a continuous barrage of stones at the cygnet who beat her wings in a frantic effort to take off, but the bombardment was on the mark and she was struck several times leaving her stunned, bobbing up and down helpless in the turbulent water. The dog they launched into the river was fast approaching, its black nose ploughing through the water towards the cygnet, and Billy knew at once what had to be done. He picked up a dead branch and leapt out into the water between the dog and cygnet. Crying with fury he lashed out at the dog’s head and drove it back until it clambered whimpering up the bank to join its masters. With abuse ringing in his ears and the stones falling all around him Billy gathered up the battered cygnet in his arms and made for the safety of the Wilderness. The bird struggled against him but Billy had his arms firmly around the wings and hung on tight.

Once inside the ruins Billy sank to his knees and set the cygnet down beside him. One of her wings trailed on the ground as she staggered away and it appeared she could only gather it up with some difficulty. For a moment she stood looking around her, wondering. Then she stepped out high and pigeon-toed on her wide webbed feet and marched deliberately around the chapel. She shook herself vigorously, opened out and beat both her wings, and then settled down at some distance from Billy to preen herself. Shivering, Billy hugged himself and drew his knees up to keep out the cold of the evening. He was not going to leave until he was sure the cygnet was strong enough to go back in the canal. He sat in silence for some minutes, still simmering with anger, but his angervanished as he considered the young swan in front of him. He started speaking without thinking about it.

‘Must be funny to be born grey and turn white after,’ he said. ‘Not a bit like an ugly duckling, you aren’t. Most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen – so you can’t hardly be ugly, can you? Course you’re not as beautiful now as you’re going to be, but I ’spect you know that. You’ll grow up just like your mother, all white and queenly.’ And the cygnet stopped preening herself for a moment and looked sideways at him. ‘Did they kill your mother too, then?’ Billy asked. ‘They did, didn’t they? What did they do it for? I hate them. I hate them. Well I’ll look after you now. You got to keep close in to the bank whenever you see anyone – don’t trust anyone, I never do – and I’ll come by each day and bring some bread with me. I’m called Billy, by the way, Billy Bunch, and I’m your friend. Wish you could speak to me, then I’d know you can understand what I’m telling you. And you could tell me a few things yourself, couldn’t you? I mean, you could tell me how to fly for a start. You could teach me, couldn’t you?’ And suddenly Billy was aware that his words were flowing easily with not so much as a trace of a stutter. ‘Teach, teach, teach, teach . . .’ Billy repeated the word each time, spitting out the T. ‘But I stutter on my T’s, always have done. T’s and P’s and C’s – can’t never get them out. But I can now, I can now. Never mind the flying, you’ve taught me to speak. I can speak, I can talk. Billy Bunch can talk. He can talk the hind leg off a horse.’ And Billy was on his feet and cavorting around the chapel in a jubilant dance of celebration, laughing till the tears ran down his cheeks. He shouted out every word he could remember that had ever troubled him and every word he shouted buried more deeply the stutter he had lived with all his life. By the time he had finished he was breathless and hoarse. He turned at last to where the cygnet had been standing but she had vanished.

Billy searched the Wilderness from end to end. He retraced the path to the canal but there was no sign of her. He found only one small grey feather left behind on the grassy floor of the chapel where the cygnet had been preening herself. This and the fact that he was still soaked to the skin from the canal was enough to convince Billy he had not been dreaming it all. As he made his way home across the darkening estate, the blue-white lights of the television sets flickering through the curtains, he practised the words and they still flowed.

He expected and received dire admonitions and warnings from Aunty May who railed against little boys in general and the price of washing powder in particular before sending him to bed early. Billy smiled to himself in his bed, hid his grey feather under the pillow and when he slept he dreamed dreams of swans or angels – he was not sure which.

When Billy’s turn came the next morning to read his page out aloud in class, he stood up and looked about him deliberately at the already sniggering children before he began. Then, using his grey feather to underline the words, he began in a clear lucid voice to read. Mr Brownlow took the glasses from his frog-eyes in disbelief, and every smirk in the classroom was wiped away as Billy read on faultlessly to the end of the page. ‘You may sit down now, Billy’ was all Mr Brownlow could say when he had finished. ‘Yes, that was very good, Billy, very good indeed. You may sit down.’ And the silence around him, born of astonishment and grudging respect soaked in through Billy’s skin and warmed him to the bone.

CHAPTER THREE

AUNTY MAY WAS ECSTATIC ABOUT BILLY’S miraculous cure from his stutter. Of course she had her own theory about the cause of this, and was not slow to voice it to anyone who would listen. ‘I’ve always said that a happy home is the best cure for all evils. That’s all Billy needed, a happy, loving home; and he’s not the first, you know. Oh no, Billy will be the fifth foster child I’ve looked after since my own boys grew up and went away. And he’s a lovely boy, one of the best I’ve had. You know, no one else would take him. Well, poor little mite, I suppose he’s not much too look at, is he? But I don’t mind that. Eats me out of house and home but we mustn’t think of that, must we? And dirty? Is he dirty? You should see the state he gets in. But there we are. Boys will be boys. After all we don’t do it for the money, do we?’

And the school too claimed responsibility for Billy’s new-found voice. Mr Brownlow was congratulated by the Head Teacher at the end-of-term Staff Meeting. ‘Quite a job you’ve done there, Mr Brownlow,’ she said. ‘Should give Billy new confidence – and the Speech Therapist had quite given up on him you know. Any idea how you managed the impossible, Mr Brownlow?’

‘It’s a slow process of course,’ said Mr Brownlow, nodding knowingly. ‘All education is you know. But I’d say patience had something to do with it. Yes, patience and faith in one’s own tried and proved methods. They love to get up and read you know. All the others were reading well, and I suppose he didn’t want to be different. I mean, who does? That’s what did it I expect. Yes, I do believe he was shamed into it.’

But the self-righteous glow at home and school soon faded as it was realised that Billy did not wish to use his new voice. He remained as silent and withdrawn as ever, speaking only when he had to and then briefly. At school he would spend hours staring at the distant trees of his Wilderness through the classroom window, chewing the end of his pencil. His confidential report read: ‘Very much below average intelligence. He always seems to want to be somewhere else. Not a good prospect.’

At home Aunty May had discovered that to threaten to send him away did indeed bring Billy back home before dark, did bring him in on time for meals. And she was not too bothered what he got up to in between times just so long as he did not get into any trouble or get his clothes dirty. ‘I’ll keep him on for a while, but I don’t like the child,’ she told the Social Worker on one of his rare visits.

‘Who does?’ came the reply.

During that winter, whenever he was not in school, Billy spent every hour of daylight in his Wilderness. He often thought of playing truant and would have done so but he knew Aunty May would have him back inside the children’s home the next day if he started that. So immediately school was over every afternoon he would make for the Wilderness, his duffle bag full of the scraps he had secreted in his pockets during school dinner. It was a hard winter that year. The ground froze in late November and the first snow came early in December. Billy saw himself as the protector of all the wild things in his Wilderness. He would spread his scraps evenly throughout the Wilderness and then watch them feed. Rampaging rooks and slow crows came wheeling in first and he would drive them away with his catapult so as to allow the smaller birds first pickings – the robins and the hedge-sparrows and the blackbirds. But he could do nothing for the barn owls, nor for the family of kingfishers. He tried. He purloined sardines from Aunty May’s larder but the kingfishers ignored them. He took some of Aunty May’s stew and put it out on a gravestone for the owls but they never came for it. He broke the ice on the canal each day so that the kingfishers could fish, but it froze over almost as he watched. He had to stand by and see them weaken as the winter wore on.