Полная версия

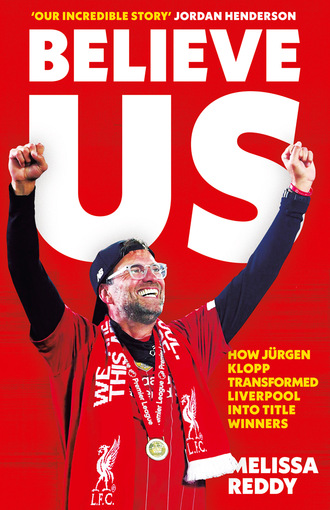

Believe Us

What Liverpool settled on was ‘a collaborative group of people working to help Brendan deliver the football side of it,’ as Ayre termed it.

The transfer committee was born with the correct idea, but under the wrong circumstances and leadership. The chief executive was part of the brains trust, which also featured Michael Edwards (then the director of technical performance), head of recruitment Dave Fallows and Barry Hunter, the chief scout. Rodgers was a key component of the committee and had ‘the final say’ on all incomings and outgoings at Liverpool, but to his chagrin, the decision-making process was collaborative.

‘I wanted to make sure that I would be in charge of football matters; that I would control the team,’ Rodgers said at the time. What he failed to understand was that he could do that while accepting the suggestions from some very sharp minds and a leading analytical research team on how to build a balanced squad for the long-term.

From the off, there were issues. During the first summer window under Rodgers in 2012, Liverpool were on the verge of signing Daniel Sturridge from Chelsea only for the manager to tank the deal because he wanted Clint Dempsey from Fulham instead and was willing to offer Henderson in part-exchange. The club had already offloaded Andy Carroll to West Ham on loan and FSG emphasised the need to bring in a striker to fortify the attack, but their advice was ignored.

Rodgers went all in on the USA international, whose valuation of £7 million at the time did not tally for a player in his late twenties entering the final year of his contract. The owners did not want to sanction a deal for Dempsey that screamed of short-termism and they were privately annoyed that the transfer of Sturridge, who would eventually switch to Anfield in January 2013, was derailed.

What really incensed them, however, was when Rodgers told the press that letting Andy Carroll go was ‘probably 99.9 per cent finance. If we’ve got a choice, then he’s someone around the place who you could use from time to time. He would have been a good option’. Rodgers would later contradict himself by stating he had the courage to get shot of the Geordie, who was Liverpool’s record signing at the time, because he didn’t fit the club’s ethos. He went further still when that window closed to fuel talk that he wasn’t being financially backed by FSG.

‘I was very confident I had a deal sewn up, but it has gone and I can’t do anything about it,’ he said on the negotiations for Dempsey, who joined Tottenham instead. ‘There’s no point me crying about it or wishing we had or hadn’t done this or that.’

Those public declarations drove John W Henry, the Boston Red Sox and Liverpool principal owner, to pen an open letter to the club’s fans explaining their methodology. ‘The transfer policy was not about cutting costs,’ he wrote. ‘It was — and will be in the future — about getting maximum value for what is spent so that we can build quality and depth.

‘We are still in the process of reversing the errors of previous regimes. It will not happen overnight. It has been compounded by our own mistakes in a difficult first two years of ownership. It has been a harsh education, but make no mistake, the club is healthier today than when we took over.

‘Spending is not merely about buying talent. We will invest to succeed. But we will not mortgage the future with risky spending. After almost two years at Anfield, we are close to having the system we need in place. The transfer window may not have been perfect but we are not just looking at the next 16 weeks until we can buy again; we are looking at the next 16 years and beyond. These are the first steps in restoring one of the world’s great clubs to its proper status.

‘It will not be easy, it will not be perfect, but there is a clear vision at work. We will build and grow from within, buy prudently and cleverly and never again waste resources on inflated transfer fees and unrealistic wages. We have no fear of spending and competing with the very best but we will not overpay for players.

‘We will never place this club in the precarious position that we found it in when we took over at Anfield. This club should never again run up debts that threaten its existence.’

Henry’s words resonate now, but they didn’t throughout Rodgers’ tenure, because there was a dual policy at play, which led to dysfunction on the pitch. Edwards, Fallows and Hunter would get their preferred targets like Emre Can from Bayer Leverkusen and Hoffenheim’s Roberto Firmino, while the manager was able to bring in his own targets with the likes of Joe Allen and Christian Benteke.

The purchase of Allen from Swansea City was another divisive episode. Liverpool were dithering over meeting the £15 million valuation for the Wales international and Rodgers, still early into the job, threatened to resign if the deal didn’t get over the line.

The hierarchy hoped this was a case of the committee finding their feet and learning how to find common ground. That was unfounded. Rodgers’ signing of Benteke from Aston Villa for £32.5 million in July 2015 — his last deal for the club — spotlighted just how fudged the strategy was. Earlier that month, Liverpool were celebrating beating rivals to the £29 million capture of Firmino, believing him to be the club’s long-term No 9. Yet they then spent even more money on a target man that stylistically contrasted with the team in order to appease the manager.

It couldn’t continue. When Rodgers first met FSG over the Liverpool job, he had produced an impressive 180-page dossier titled ‘One Club, One Vision’, but there was no unified approach during his tenure.

Henry was right. Liverpool were ‘close to having the system we need in place’, but it required an elite figure to completely believe in it and to galvanise it. Fortunately, they knew just the man for that.

2

The Perfect Fit

‘From tomorrow I will be the Liverpool man 24/7.’

Jürgen Klopp

‘We’re hitting for the cycle,’ John W Henry smiled to FSG chairman Tom Werner and its president Mike Gordon. In baseball, the terminology refers to the achievement of one batter recording a single, double and triple hit as well as a home run in the same game. It is uncommon and one of the most difficult feats to accomplish in the sport.

As the trio took in the East Manhattan skyline from a 50-storey skyscraper housing the offices of law firm Shearman & Sterling on Lexington Avenue, they were primed to swing big in a meeting they believed had the power to reshape not just Liverpool FC but the football landscape.

Henry was equating being on the cusp of hiring the perfect manager for the club — an incredibly complex criteria to meet — to hitting for the cycle. No fanbase deifies the main man in the dugout as vociferously as Liverpool’s: through banners, in song and the manner in which they are tattooed to the very soul of the institution. It’s a phenomenon that stretches back to Bill Shankly’s appointment in 1959, with the Scot transforming a club in the Second Division into a ‘bastion of invincibility’ during his 15-year dynasty.

Equally, no fanbase are as demanding of what they want in their leader. At Anfield, the requirements stretch well beyond what a CV reads or being tactically excellent. You need to win, connect with supporters and represent the essence of Liverpool on a cultural, political and spiritual level. In summary, a top manager must also operate as a man of the people while illustrating he is bigger than the job, greater than the expectations and unwavering in his handling of the fiercest criticism.

In New York on 1 October 2015, FSG were confident they were going to hire that very figure. A magnetic individual who had the proven capacity to galvanise, rejuvenate and deliver sustainable success to a club, while also having a lasting impact on the place and its populace.

‘It’s the right guy at the right time,’ Gordon noted. But the owners had selected the wrong choice of day for their first face-to-face interaction with Jürgen Klopp. The meeting coincided with the annual gathering of the United Nations general assembly, which gridlocked New York. The German’s journey from JFK Airport to Lexington Avenue took six hours in snaking traffic, and while it was unwelcome, it didn’t diminish his ‘highest enthusiasm’ for the opportunity to outline his vision for Liverpool.

Long before Klopp stepped into the building, the job was his. It was not an interview, rather a confirmation of what FSG already knew about the two-time Bundesliga winner courtesy of a call, a Skype conversation, and crucially, a detailed 60-page dossier on his way of working. Compiled by Liverpool’s esteemed head of research, Ian Graham, and Michael Edwards, who was technical director at the time, it evaluated everything from the manager’s training sessions, reaction to setbacks, achievements in relation to his resources as well as his interaction with staff and players through first-hand testimony from his former clubs Mainz and Borussia Dortmund. The more Liverpool drilled into Klopp’s methodology, the greater their conviction was that he could unify the core areas of the club and elevate it.

Beyond the comprehensive document, FSG knew he was their guy because they had previously pursued him twice. Each time they sought a manager, he stood out and tallied with their long-term thinking. Towards the end of 2010, as Roy Hodgson was scraping through a painful spell at Liverpool’s helm that would eventually span only 31 games in charge, the group used a third party to ascertain whether Klopp would consider leaving Dortmund to move to Anfield. It was no surprise the answer was negative, given he was successfully re-establishing BVB as a Bundesliga and European force while they played irresistible, high-pressing football.

A year later, another tentative approach was made when club legend Kenny Dalglish, Hodgson’s replacement, was released from his second stint at Liverpool. ‘I have been made aware of interest in England, and it is an honour to be linked with big clubs in the Premier League,’ Klopp said, before emphasising, ‘I love it here [at Dortmund] and have no intention of changing clubs.’

Naturally, Liverpool were not the only English team trying to secure the elite manager, who had halted, at least temporarily, Bayern Munich’s monopoly on being Germany’s best. Winning back-to-back Bundesliga titles and bulldozing opponents in the Champions League, where Dortmund reached the final in 2013, meant that interest in Klopp ballooned — especially 30 miles away in Manchester. While Dalglish’s successor as Liverpool manager, Brendan Rodgers, was overseeing poetry in motion on Merseyside in early 2014 with a Luis Suarez-powered offensive line taking the club close to the title, David Moyes was horribly floundering at Manchester United. Sir Alex Ferguson’s successor was well out of his depth and urgent action was necessary to remedy the club’s demise. Their executive vice-chairman, Ed Woodward, scheduled a chat with Klopp in Germany to sell him on making the switch to Old Trafford.

The BVB trainer hugely admired Ferguson’s achievements and the manner he went about establishing United as a global juggernaut, which is largely why he agreed to the encounter. Woodward’s pitch, however, was the antithesis of what would appeal to Klopp. He spotlighted their financial might and offered an Americanised picture of blockbuster names and entertainment while likening United and Old Trafford to the game’s Disneyland.

Klopp, a football romantic who feeds off emotion and who counts time spent on the training pitches as more fundamental than transfers, was turned off.

That came as no shock to Christian Heidel, the former sporting director of Mainz. He has a three-decade relationship with Klopp and was the one who offered him the chance to instantly progress from being a player to the club’s manager. ‘Emotionally powered’ is one of the core descriptors he uses for his friend, who is also a ‘fighter’ and ‘builder’. Heidel knew Klopp’s powers could only be properly unleashed at places that resonate with his own personal experiences. Being at United and having an unlimited budget would jar with a life shaped by scaling adversity and making the most out of little.

Klopp’s formative years in Glatten, a tiny but picturesque town in the Black Forest, were simple. His late father, Norbert, who had been a promising goalkeeper and earned a trial at Kaiserslautern as a teenager, worked as a salesman specialising in dowels and wall fixings. He was a ruthless competitor, extracting the maximum from his son by never taking it easy on him, whether it came to skiing, tennis, football or sprints across the field. Norbert impressed on him that it wasn’t worth doing anything without full dedication. He taught his son that ‘attitude was always more important than talent’, promoted a ferocious work ethic and schooled him in the art of resilience.

Klopp junior, a Stuttgart fan, had an unsuccessful trial with his boyhood club and did not become a professional footballer until he was 23. In the interim, he turned out for Pforzheim, Eintracht Frankfurt II, Viktoria Sindlingen and Rot-Weiss Frankfurt while working part-time in a video rental store and loading lorries. He juggled that with taking care of his toddler, Marc, while also studying for a degree in sports business at Goethe University Frankfurt.

‘Life took me a few places and gave me a few jobs,’ Klopp noted. ‘It wasn’t about where I could be, but about doing what I had to do, because I was a young father and needed to provide.’ After finally landing a pro contract with Mainz in 1989 as an industrious but technically-limited striker, Klopp still took steps to invest in his future for the benefit of his family. Earning just £900 a month, he signed up to the legendary Erich Rutemöller’s coaching school in Cologne. Twice a week, he would undertake the 250-mile round trip to enhance his tactical understanding of the game.

Klopp also sponged off Wolfgang Frank, the late Mainz coach who was inspired by Arrigo Sacchi’s Milan. He would spend hours talking to him about systems and the secrets to overpowering better resourced opponents. ‘Under Wolfgang Frank, for the first time in my career, I had the feeling that a coach has a huge impact on the game,’ Klopp would reveal. ‘He made us aware that a football team is much more independent of the class of individual players than we thought at the time. We have seen through him that it can make life very difficult for the opponent through a better common idea.’

Frank was one of the first German managers of the era to shun using a sweeper, which was the norm, opting for a four-man zonal defence and a midfield diamond shape. He espoused high-pressing, attacking from inside, offensive protection and overloading the flanks — all hallmarks of Klopp’s teams to the present-day Liverpool.

Those tactics became the blueprint for Mainz in February 2001 when manager Eckhard Krautzun was sacked by the club on the eve of an away game and sporting director Christian Heidel called an emergency summit with senior players. It was decided at the meeting that Klopp, who had been converted to a defender from a striker, would undergo another transformation and become their new manager. The choice was unanimous and as with his playing career, the need to defy convention and recover from setbacks would be the driving force in his new managerial setup.

Klopp is unrivalled in dealing with massive disappointments and moulding them into both lessons and motivation. ‘Even when you don’t want defeats, when you have it, it is very important to deal with it in the right way,’ he said on looking back at his career in the game. ‘I had to learn that early in my life, especially my coaching life. We had so many close failures: like with Mainz not going up by a point, not going up on goal difference, then getting up with the worst points tally ever; Dortmund not qualifying for Europe, then losing a Champions League final. I am a good example that life goes on. I would have had plenty of reasons for getting upset and saying, “I don’t try anymore.”

‘Obviously, it is not easy to go through these moments, but it is easier to deal with it because it is only information, and if you use it right the feeling is good.’

That is pure Klopp. And it was why Hans-Joachim Watzke, Dortmund’s CEO, was convinced he would reject United’s offer. Their money-based pitch clashed with rather than complemented the manager’s make-up. In the second week of April 2014, Klopp told Watzke he’d be swerving the chance to take charge at Old Trafford. As he once summarised: ‘You can be the best in the world as a coach, but if you are in the wrong club at the wrong moment, you simply don’t have a chance.’

Enquiries from Manchester City and Tottenham would both also be rebuffed a few months later. A year after shunning United, however, Klopp’s circumstances at Signal Iduna Park changed considerably.

With Dortmund regularly ceding their greatest talents to European football’s apex predators — chiefly Bayern — they found that continuing to usurp their powered-up rivals in the Bundesliga was becoming too taxing. BVB’s results were no longer as good as their performances, with staleness and a sense of comfort creeping in. During a press conference that reverberated around the world on 15 April 2015, Klopp announced he would be leaving Dortmund at the end of the season. At the time, the club were 10th, 37 points behind Bayern. The city in Germany’s North Rhine-Westphalia was enveloped in sadness.

‘I always said in that moment where I believe I am not the perfect coach anymore for this extraordinary club I will say so,’ Klopp stated. ‘I really think the decision is the right one. I chose this time to announce it because in the last few years some player decisions were made late and there was no time to react.’

Fast forward five months and the atmosphere couldn’t have been more of a contrast in an expansive boardroom at the New York offices of Shearman & Sterling, where over the course of four hours, Klopp sketched his plan to restore Liverpool as a global and continental powerhouse.

He addressed the lack of an on-pitch identity, which would be the first facet to rectify, and also pointed out the importance of harnessing the emotional pull of the fans. From the academy through to the first-team operation at Melwood, Klopp outlined a blueprint for the club’s playing style and standards to be aligned. For Liverpool to have any chance of becoming a force again, he reasoned, they would have to operate as one formidable unit.

Mike Gordon remembers being ‘in awe’ of Klopp, not on account of his magnetic personality, but the substance of his strategy and the concise yet convincing way he delivered it in a second language.

It is why, just an hour into spelling out his vision, FSG told Klopp’s agent, Marc Kosicke, that their lawyers had begun drafting his contract of employment. When the juncture came to discuss personal terms at the end of the talk, the manager excused himself and took a walk through Central Park. As Klopp stood soaking in the sights of the Hallett Nature Sanctuary, it dawned on him that it was not the type of surveying he had originally contemplated after his break from football.

As a player, he was fascinated by watching how managers work — from implementing their philosophies to handling different personalities, balancing squad dynamics and drafting plans that extended beyond match preparation. Klopp had resolved to travel around Europe to absorb as much knowledge as possible from coaches when he hung up his boots. However, his immediate transition from pulling on a shirt for Mainz to becoming their manager paused that idea for seven years. Switching from the Opel Arena to Dortmund further shelved it for the same amount of time and now Klopp was fresh off a four-month sabbatical and about to become Liverpool manager.

That night, when he returned to his suite at the Plaza Hotel, he thought about how he wouldn’t change anything about his path, his choices or the timing of them, relating as much to his wife, Ulla Sandrock.

That same evening, Liverpool stumbled to yet another dispiriting draw at Anfield. The sound of the final whistle against FC Sion was met with booing for the third time in four games at the famed ground. Over in the Bronx, the Red Sox were defeated 4–1 by the Yankees, their greatest rivals. Yet those results couldn’t dilute FSG’s celebratory mood after finally securing the manager they had coveted since their takeover of Liverpool in 2010.

Back at Melwood, it was hard to escape the feeling that Brendan Rodgers’ time was running out. After Liverpool’s 1–1 draw at Goodison Park on 4 October that left them 10th in the league table, Rodgers was driving back home, when he received a phone call from Mike Gordon relieving him of his duties. News of his departure quickly broke, with Klopp’s status as the prime candidate to replace the Northern Irishman dominating the coverage.

Conversations at Liverpool’s training complex centred around him being so heavily linked with the job. ‘There was such a buzz and he was really high profile as well, which got the lads going,’ Adam Lallana recalls. ‘I remember us sitting in the canteen discussing that he ticks all the boxes for Liverpool. We weren’t going to outspend the likes of City, United and Chelsea and he wasn’t a big-money manager. He had a history of improving clubs by making the players he had better before building on that base. We spoke about games we’d seen of Dortmund, about things we’d read or heard about the gaffer and there was so much excitement around the place.’

Jordan Henderson was at the Bernabeu in April 2013 to watch BVB line up against Real Madrid in the second leg of their Champions League semi-final. Dortmund took a 4–1 advantage to Spain and lost 2–0 after late goals from Karim Benzema and Sergio Ramos, but still progressed to the climax of the competition at Wembley.

‘I was fortunate enough to go watch Dortmund against Madrid at the Bernabeu and I was really blown away by how clear their identity as a team was and how they controlled large parts of such an important game against a side with superior resources,’ Henderson says. ‘They lost the match, but it didn’t matter because they managed the tie well and you expect to be put under pressure by Real, especially when they’re at home and need to win, but Dortmund handled it.

‘When the gaffer was linked with us so heavily, I thought about the experience of that game and how positive everything around him and Dortmund felt. I was all in, and to be honest, a lot of the lads were desperate for it to happen. We knew his success with Dortmund was no accident and you could tell he was a special manager that could make a big difference.’

Carlo Ancelotti was the other candidate under consideration by FSG. While there was no questioning the Italian’s pedigree as a three-time Champions League winner, he did not generate enthusiasm around the club. The owners were put off by his focus on rebuilding through transfers and he seemed to be more of an overseer of good teams rather than a constructor of one. The majority of players were of the belief that Ancelotti would want to secure success through immediate investment instead of attempting to bring the best out of them over time. The staff, meanwhile, had heard from colleagues within the game that the man who led Real Madrid to their 10th European Cup could be detached and didn’t do much to uplift or inspire his squad or those behind the scenes.

‘With Ancelotti, the general feeling was he wouldn’t be the worst appointment because of his past accomplishments,’ remembers one member of Liverpool’s conditioning staff. ‘But it was like you had to explain to yourself why he would be good for the job. It was the opposite with Klopp — everyone was bouncing around the place at the thought of him becoming the new manager, because it just made so much sense.’

The bulk of Liverpool’s fanbase subscribed to the same thinking. They had been motioning on social media since 2014–15 for the German to take charge at Anfield under the ‘Klopp for the Kop’ tag and when it became clear he would succeed Rodgers, the boos and toxicity that marked the previous months were swept away by a groundswell of optimism.