Полная версия

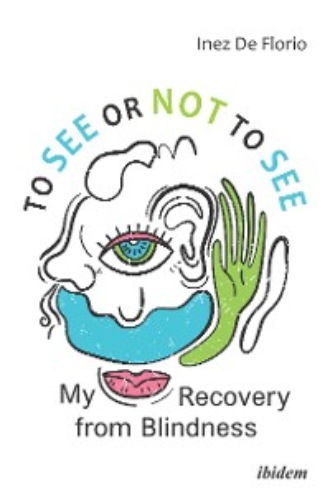

To See or Not to See

As the electricity often failed, we did not have to wait for the bell to ring at the end of the lesson. Mrs. Melzer was free in the timing. Furthermore, she had a fairly precise idea of our learning possibilities. The lessons were tailored to our individual needs, and when we had done our daily workload, we were allowed to go home. As I was dependent on Renate, I tried as best I could to help her with the tasks that were difficult for her.

“Well, David, my primary school teacher was very responsive to each of us. The good ones got more challenging tasks, while she dealt with the weaker ones.”

“You were very lucky. By the way, in the first years after the war, not everything was as regulated as it is today. It was no different with me. Our Mr. Lehmann, already high in his seventies, was empathy in person. But today …”

“Do you know what you want to become?”

“Yes, for over a year now. I’m going to study psychology; later on, I’ll open a practice. I’ve already chosen the suitable university.”

“Which one?”

“I want to study in Mainz; I have even enrolled.”

“Already? You still have time until you graduate.”

“Yes, but as most universities they have long waits in psychology.”

Finally, it was the turn of Jailhouse Rock. First David controlled my movements, then we rocked independently. I was very delighted. But soon I lost, as so often, the sense for the right direction. Without intent I landed on David’s body like in a hug. And what did David do? He grabbed me gently but decisively by my upper arms and pushed me away. I muttered something about apologizing.

“No problem. That can happen.”

Before I could reply anything, we heard someone unlock the apartment door. David’s father came into the room.

“Hello, Cecilia, how nice of you to come upstairs.”

“Yes, David taught me the hip swing of Elvis. I can do it pretty well now.”

“Fine, that’s really vital these days!” He laughed. “Well, don’t let me interrupt you. I have to finish an urgent report for tomorrow.”

We made one or two more attempts with Teddy Bear, but somehow the air was out. Finally, I said goodbye and David brought me downstairs to the front door.

The experience worried me. In the following days I thought about it a lot. But it wasn’t like a missed opportunity. No, it was something quite different. The insignificant event brought me to the question that I often asked myself: What did I look like? What effect did my appearance have on others? Was I attractive? I asked everyone again and again—my family, our acquaintances, my friends. They described me as tall, slim, blond, with green eyes. But that did not answer my basic question: How did I appear to the opposite sex? Moreover, I was aware that probably nobody would have confronted me with the truth. Who would tell an almost blind girl that she was not particularly attractive? Was a visually impaired person not punished enough?

I kept thinking about this. What would a girl look like, that David could fall in love with? I could hardly imagine. The longer I thought about it, the more I realized that I had never heard of a girl in connection with David.

At my next opportunity I interviewed Alina. I thought my question was very clever:

“Tell me, do you know David’s girlfriend?”

“What do you mean?” Alina returned baffled.

“Well, if he has a girlfriend, then you surely know her.”

“David never had a girlfriend.”

“What do you mean?”

“Can’t you guess?” came another counter-question from Alina.

“Do you want to say he is not interested in girls?”

“Exactly. Haven’t you noticed that David is almost exclusively with boys?”

Even thinking about it carefully, I had never noticed that. When we met in the schoolyard, it was always David who came up to me to have a chat. How could I have noticed that he had previously only been with male schoolmates? I explained it to Alina who immediately apologized:

“How stupid of me! Please excuse me. But while we are on the subject: May I ask you something?”

“Oh, sure.” I was curious.

“How do you find out that you like someone? I mean, a man.”

“There are many reasons. First of all, I always listen carefully to what he says and how he says it.”

“OK, then you’ll know if he’s a smart guy or a blather. So what?”

“The most important thing is the voice. Does it have a sound that somehow attracts me, that sets off a vibration in me. Breathing is also important. Does it go together with what he says?”

Alina was really the optimal conversation partner for me. This was confirmed by her next question:

“Do you mean to say that you soon notice if someone is lying or telling the truth? If someone is honest?”

“Sort of.”

“I never thought about that. I suppose there are other qualities one can’t really do anything about, but which are important to you.”

“Yes, the body odor is also important, or more precisely the body heat that one radiates. I also find soft hair on the arms very erotic.”

“Fantastic!” Alina was pleased.

“But you must not forget the disadvantages: I never know how old someone is or what he looks like.”

“Don’t let it bother you. You’ll come to know as time goes by. You only have to ask someone. Me, for example!”

“Thank you. I’ll take you at your word.”

“I’ll be pleased. Maybe I’ll like him too.” She laughed.

3 Blind is the one who refuses to see

Man’s basic vice, the source of all his evils, is the act of unfocusing his mind, the suspension of his consciousness, which is not blindness, but the refusal to see, not ignorance, but the refusal to know.

Ayn Rand

Perhaps only in a world of the blind will things be what they truly are.

José Saramago

After our return from Italy, the next medical consultation was only a matter of time. But: Did I really want to undergo eye surgery? That was what I asked myself again and again. As I said, I had reconciled myself to my severe visual impairment decades ago. But that did not mean that I was not missing some things. In this respect, I was different from Saliya Kahawatte and Isaac Lidsky, who considered their lives fulfilled even without eyesight. The more I thought about it, the more I noticed certain shortcomings.

Two matters in particular kept coming to my mind. On the one hand, I would have liked to be independent of other people. Although those who helped me did not show at all the possible burden, I would have liked to plan my time independently from other people. I often had to orientate myself according to the time possibilities of my helpers. On the other hand, I sometimes felt that communication with friends and acquaintances was insufficient. In one-on-one communication most of them took my possibilities into account; they tried to formulate their thoughts clearly and unambiguously. In conversations with friends or acquaintances, however, I often had difficulty following the conversation: I had to assign voices, make sense of pauses in speech and, above all, interpret the individual statements without being able to orient myself by facial expressions and gestures. I was convinced that I would be able to follow the conversations better if I saw the individual speakers.

Of course, I also thought about the failure of the intervention, but I did not really fear it. The prudent behavior of the Russian surgeon had shown me that the ophthalmologists who wanted to test the new procedure did not do so without consideration, if only to avoid setting negative precedents right at the beginning. Whether or not I would have thought of a corresponding operation without the intervention of my husband, I do not know. Probably I would not have found out about the new procedures so early. But my husband was certainly right: Why shouldn’t I expand my four senses to include the visual sense? Thus, I decided to try vision if there was a promising possibility.

The most urgent question I had to ask myself in this context was rather: What would it be like if I suddenly saw? I could not get an idea of it. I would have liked to exchange views with other people concerned, but there was nobody in my environment who could have told me anything about it. Even my eye doctor, whom I visited now and then, remained silent. Although he welcomed my intention to undergo surgery, he had no first-hand experience. In his practice there was no case comparable to mine. Therefore, I questioned my husband, who had informed himself in detail.

“I find it rather difficult to suddenly be able to see when you don’t know what seeing is.”

My husband did not play down the difficulties, but said:

“Yes, it’s certainly one of the greater challenges. I have read a lot about it. You need a strong will and quite a lot of perseverance, especially in the beginning. You really have to learn how to see.”

Not satisfied I dug deeper:

“And what if it doesn’t work? Are there any patients for whom seeing was not an enrichment, who failed to learn to see?”

“Yes, but unfortunately, there is a lack of solid, recent evidence. It is reported that many people who underwent cataract therapy have not been able to cope with seeing. This may have been partly due to outdated surgical procedures.”

“And what happened to them? Have they gone blind again?”

“No, not that, at least as far as I know. But a relatively large number committed suicide.”

“Oh dear,” I exclaimed in dismay.

But my husband knew how to calm me down.

“With all of this, you must remember that they were often reluctant for, or at least indifferent to, the operation. And they were not aware that one must learn to see. They made no effort whatsoever. Moreover, some of them suffered from serious illnesses even before the operation. I am convinced that if you don’t give in to the illusion from the beginning that seeing comes naturally, you will succeed. You have to do something about it.”

“If I understood you correctly, it’s definitely very hard to conquer the visual world.”

“Aptly put! But I will assist you in conquest when the time comes.”

You might ask now: Don’t you just have to open your eyes and see? Or is it a kind of Sleeping Beauty who is kissed awake by a prince? Since Sleeping Beauty is known to have seen the world until she was 15, it was only a kind of time travel after that the well-known fairytale figure had to find the connection to the here and now. This is not an easy task either, but not to be compared with the effort one has to make when, blind from birth, starts seeing in adulthood.

My husband had further explanations at the ready:

“There is a big difference between congenital and acquired visual impairment. It is quite different if you have seen more or less well all your life and then gradually lose your sight as you get older, due to cataracts or other age-related eye diseases.”

“Does this mean that after cataract surgery, such patients do not need to learn to see because they return to a previous positive state?”

“Exactly that.”

After a few years, doctors in Germany also performed comparable operations, usually with good to very good success. A colleague had heard about a clinic in the Rhineland through his daughter—she studied eye medicine—whose chief physician had already successfully operated on several severely visually impaired and even blind patients. In the meantime, he was known far beyond the German-speaking countries. We went to see him and he approved the intervention. Although I was already in my late forties, the operation, which I will describe in more detail later, brought the desired success, also because the retina of both eyes was largely intact.

After the successful surgery, friends and acquaintances congratulated me without exception. “This must be like winning the lottery for you” or: “Now your life really begins.” They simply could not imagine how difficult it is, to learn how to see if one has been blind or at least severely visually impaired since birth or early childhood. They had no idea of the effort required to process optical impressions in a reasonable and meaningful way. The main reason for the difficulties is that people who were born blind or severely visually impaired cannot rely on experiences that help sighted people process incoming visual impressions. The moment when the nurses removed the bandages from my eyes was only the first stage on my arduous journey from darkness to light.

Years later, a friend gave me a book entitled An Anthropologist on Mars.17 The author is the late British neurologist Oliver Sacks, who describes complex clinical pictures in his numerous popular science books with the intention of not losing sight of the people concerned and of recognizing the individual circumstances behind each illness. He accepts long journeys in order to visit the patients in their home environment and to interact with them privately. But Sacks does not go beyond the role of the benevolent observer. After all, he is a doctor and therefore primarily interested in clinical pictures.

In the mid-1990s, Sacks reported that in the last few centuries up to the 1980s, there were only about a dozen people who were freed from their blindness by a successful operation at an advanced age, or better: who came to see. Thus, in one of the seven episodes of the aforementioned book, he describes the case of Virgil, who was successfully operated on in the same year as myself, that is in 1991.18 Although Virgil and I were about the same age at the time of the surgery, our stories were very different.

One reason for this is the initial situation: Virgil was not only severely visually impaired, but was considered to be completely blind. In addition, he had numerous serious pre-existing medical conditions. Above all, however, he was indifferent, if not hostile, to the operation that his fiancée had urged him to undergo. Virgil did practice, for example with toys, to be able to classify objects better. But one has to deal with the same perceptions in reality over and over again until the brain can interpret the visual input accurately and assign meaning to it. It seems as if learning by doing had been an enormous psychological burden for Virgil. I also found it difficult to repeat the same processes—with slight variations—several times, but it was manageable, especially when I could see progress. Above all, however, I was aware that it was a matter of building a new identity if you did not want to become a blind person who could see. Ultimately, the psychological disposition is decisive.19

Sacks is primarily interested in medical and psychological facts; he visits Virgil in his hometown together with a colleague in order to question him and perform a series of tests. In my opinion, the conclusions he draws from the cases presented in the literature are too negative. Sacks is always talking about the patients’ problems with their newly acquired sense of sight. It is possible that only the problematic cases were recorded, because Alberto Valvo (1972) proves that there were also positive developments: “Once our patients have acquired visual patterns, and can work with them autonomously, they seem to experience great joy in visual learning … a renaissance of personality … They start thinking about wholly new areas of experience.”20

How I gradually succeeded in bringing the sense of sight in line with other sensory experiences is explained in the following with the help of numerous details, especially those that are particularly relevant for an adequate assessment of eyesight. As far as I know, I am the first to tell you about these strenuous learning processes, including the setbacks, but also the small and large successes, at first hand. Although there are numerous publications dealing with blindness in literature and visual arts21, they cannot be compared with my experiences. In addition, there are the descriptions of blind people themselves. Similar to Helen Keller, most of them report on how they deal with their blindness.

I became acquainted with these reports and stories over time, because when I had completed the literacy course without much problems—also thanks to the prudence of my former primary school teacher—friends and acquaintances overwhelmed me with books written by blind people and about blindness in general.

I was particularly impressed by the description of the French writer Jacques Lusseyran, who went blind at the age of eight. Nevertheless, he joined the French resistance movement during the Second World War. After his liberation from the Buchenwald concentration camp, he published several books. A distant relative had given me his book And there was light: The extraordinary Memoir of a blind hero of the French Resistance in World War II.22

Little by little I also received the literary works of sighted authors, such as The Country of the Blind by Herbert George Wells from the beginning of the 20th century23 or The City of the Blind by José Saramago from the 1990s24, in which blindness is mainly used as a metaphor. However, none of these books has impressed me as much as Lusseyran’s. If you have had to struggle with blindness yourself, you can empathize very well with the story of a blind person.

To my knowledge, there is no autobiographical work to date that tells the story of how tiring, but also how satisfying and rewarding it is to learn to see after decades of blindness or severe visual impairment. Even the book Blinder Galerist (Blind Gallery-Owner) by Johann König does not change this.25 The report that König, son of the well-known art connoisseur and museum director Kasper König, wrote together with Daniel Schreiber, inevitably bears similarities to the descriptions of other blind or visually impaired authors.

But his case is quite different. When Johann König became almost completely blind in the early 1990s due to an accident while playing with a starting pistol, he was already twelve years old. Up to this point, he had intensive contact with visual impressions through his father: Kasper König took him already as a toddler to exhibitions and the museums he directed. The 30-page picture section inside the book bears witness to this. At home, Johann was also surrounded by art connoisseurs and above all by well-known painters and sculptors, who regularly visited the König family—mother Edda was also interested in art. Johann’s sense of sight was therefore already very well developed at the time of the accident.

In the two years after the accident, Johann was operated on more than 30 times, sometimes with minor successes, which never lasted long. Finally, he attended the well-known German Institute for the Blind (BLISTA) in Marburg, where it was now possible to take the Abitur, the qualification granted at the end of secondary school. Living in a boarding school with other blind children and young people was an enrichment for him, as he was able to determine his own life to a large extent—unlike at home. When he had to realize that he would be denied a career as an artist, he decided to open a gallery.

In 2002, shortly before his high school graduation, he founded a gallery called Johann König, Berlin, which was initially in the red, but within five years became one of the most important international galleries for modern art. After innumerable further operations, a special corneal transplantation procedure finally leads to a remarkable success in 2007. König recovers 30–40% of his sight. He describes his joy and relief, but has no difficulty whatsoever with his regained vision. The main focus of his book is on modern art, the art business and especially on his professional activity as a gallery-owner. These descriptions make up more than seventy percent of the text. König’s message is: Even with such serious limitations, you can make it! He substantiates this statement with numerous quotes from recent literature. Johann König is not a blind gallery-owner; he was blind when he founded his gallery and ran it with a team of employees from 2002 to 2007, the year of his most successful operation to date.

Up to now nobody before me has ever described what learning to see means for the assessment of the sense of sight and the perception of each individual. The fact that I have largely succeeded in learning to see is certainly due to the fact that I was not completely blind, but could distinguish light from dark. On the other hand, I would not have come so far without the empathy and support of my husband. Oliver Sacks also reports on the corresponding learning processes, using Virgil as an example, but at second hand. In addition, Sacks takes on the role of the observer, as already mentioned. He shows great understanding for Virgil, but, like all the patients he describes, he does not give him any psychological help. Yet appropriate psychotherapeutic treatment should have been offered long ago—in connection with this kind of surgery.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.