Полная версия

Do not Disturb! I'm Drawing

ibidem-Press, Stuttgart

Contents

Introduction. How do we help the cild to be creative and self-assured?

Chapter One. A look into art therapy

Chapter Two. "Scribbling," drawing and self-esteem-how do they relate?

Chapter Three. The drawing, the “me” and the soul of the child: changing and evolving together

Chapter Four. From the doodle to the circle and on to drawing a figure

Chapter Five. Can I now bring a figure to life?: ages four to six

Chapter Six. How to build a house—or a house isn’t only a square: ages four to five

Chapter Seven. All the colors of emotions—drawing with color

Chapter Eight. A private collection from doodling to drawing a figure —by a girl and a boy

Chapter Nine. From the doodle to the circle— a universal phenomenon

Chapter Ten. The soul, the doodle, and circles in adults

Chapter Eleven. “Please Do Not Disturb—I’m drawing” Your toolbox (and some tips, too)

Chapter Twelve. “Take a look at the drawing: it’s a body” Drawing as an expression of the body

Chapter Thirteen. An activity for keepsake

Thanks

Bibliography

Introduction

How do we help the child to be creative and self-assured?

DO NOT DISTURB—I’m Drawing, deals with the development of drawing in children aged one and a half to six. It explains the meaning of this process, and describes how the parent (or any other observer) can encourage and influence throughout different development stages. The book will provide you with tools that will help you support your children to help them become more creative, joyful, communicative and self-assured.

The book provides us with answers to questions such as: When and how do the doodles and the lines first appear, and why is this so meaningful? When does the circle begin to “grow horns”? What is the meaning of the triangle? When does the child begin to mark a cross, and what’s so special about that? What emotional changes take place within the child during each of these graphic changes?

From doodling to forming a figure—the progression in the child’s drawings has a fixed order all around the world, and has a psychological and emotional logic to it. Understanding this order will provide the reader with meaningful insights about the child’s inner, emotional world. The objective is to evoke curiosity and enthusiasm within you and to make you, the observer of your child’s drawings much more exciting.

Understanding these different stages of emotional and motor development—and unraveling the “hidden secret” of the relationship between them—will help you to accept the child and their abilities at every given moment of his development. Observing the child’s drawing with an accepting, appreciative, enthusiastic gaze will grant the child the validation of being understood, and strengthen his will to create. Who amongst us, children and adults alike, doesn’t want to be understood and appreciated?

Reading the book will also help you, (whether you are a parent, grandparent, therapist or teacher), to understand the child and encourage him to create and express himself. It will help you to add to the child enthusiasm, vitality, imagination and meaning, and thus reinforcing the child’s self-esteem. As a result, you and the drawing child will be able to connect and communicate on a much deeper level.

* * *

I am an art therapist with many years experience in the field. Throughout the years, I have researched, taught and accumulated a significant amount of experience and knowledge about the development of children’s drawing as a process that runs parallel to their emotional development. Nowadays, I use the experience and knowledge I’ve gained in order to help children, teens and adults.

I also teach and guide other art therapists. I’ve heard many therapists and teachers say,“Ah, I’ve already learnt a lot about the development of children’s drawings. There are so many books on this subject.”

“And do you remember anything?” I ask. “Not really,” they answer with a smile.

In order to help you really internalize and remember the process of the development of children’s drawings, I will give you a unique insight into the connection between the child’s emotional and motor development through their drawings, one which I have developed throughout the years. Your manner of observing the drawing, accompanied by a real understanding of the connection between the child’s motor and emotional development, is going to change and influence you after reading this book. This understanding will help you develop a more accepting, supportive, appreciative and enthusiastic observation (not necessarily in a verbal way). The way you observe is very important to the child’s development. It increases his self-esteem, his love for creation, his curiosity and his motivation to keep and create, and also deepens the connection between the young creator and his observer.

During the process of writing this book, I have (more than once) imagined myself as a straight line aiming at a target. Even if the line occasionally bent, in the end it always returned to being straight. What helped it straighten was the enthusiasm of whoever read the book in the process of writing it, even at its early “doodling” stage. Such enthusiasm has encouraged me and evoked within me the need to continue to write. The strength to keep writing came from my desire to give away my knowledge and share my excitement over the lines, colors and shapes that teach us about ourselves in a unique and precise way.

Throughout this book, I will empathize the meaning, the complexity and the importance of the role of the parent or any other observer. I will help any observer to manage to express honest enthusiasm for the child’s doodles. I will focus on the development of the child’s drawings and explore the connection between the motor movement in his drawings and the meaningful emotional progression that occurs simultaneously.

I hope to demonstrate the importance of being genuinely impressed by the child’s creative expression, starting from his early doodles. Any expression of approval and honest excitement in the moment of creation will encourage the child later on to develop autonomous and original thinking. The tendency to show the child how to draw a house or a figure, and even to occasionally correct him and teach him what is the “right” way of drawing, could damage the child’s confidence and leave him with the constant need for guidance and direction from others who (allegedly) know better what to draw, and how.

An authentic expression of enthusiasm for the child’s drawings, on the other hand, will strengthen him and encourage him to become an independent and original thinker as an adult. Therefore, it is essential that every person who raises a child, or works with him, will learn the stages of this development in children’s drawing skills, for it is an important key for forming closeness with the child and for understanding him. In this book, I will share with you the secret of these stages.

My curiosity to this subject arose during my studies in psychology, when I discovered the books of the psychoanalyst, Frances Tustin. Tustin researched the world of the autistic child, as well as the autistic situation in general. To my surprise, I discovered that Tustin shows her enthusiasm for each coincidental cross in the therapy room that a child recognizes, even if it’s only a part of a window frame. She interprets it as a sign of meaningful emotional development. This realization strengthened within me the understanding that there is a meaningful and fascinating connection between graphic shapes and a child’s emotional development. Over time, I discovered another rich world of relationships between shapes and meanings. When I share these insights with my students, they all enthusiastically report a change that occurs in their approach toward doodling, and toward the early drawings of their own children and patients, and they all mention how much this new attitude influences the creativity of these children.

Later, I also found a resemblance between the process of development in children’s drawing and the process of development in the drawings that were drawn by the adults with whom I work. It was interesting to discover that adults drawings demonstrate a similar, parallel relationship between the two processes of emotional and graphic development. That way, through the process of creation, many doodles and drawings of crosses and circles were created, enabling a person to redefine his own “self,” to enhance it, to rearrange the process of his separation from the “other” and his connection to the “other,” and also to improve the quality of the dialogue between his internal and external world.

I have designated the final pages of this book to the documentation of the children’s drawings, so that, later on, they can serve as a reminder for your child of this particular process of transition from doodling to drawing a figure. Adults always like to know what has happened in the past, and how they were when they were little. These drawings are a testimony of an exciting and important process of progression. This can help your children—in the present and in the future—to have a better understanding of who they are, and will most likely contribute to the realization of how much they were, and still are, important to you.

Try to imagine this: in front of you is a drawing you drew when you were three years old. How do you feel when you look at it now? How does it feel to have an almost tangible grasp on a scrap of your own childhood? Once, I attended a school reunion to which someone brought a booklet of her classmates drawings, which had been given to her when she was sick. Even after all those years, the excitement this booklet brought about was huge, and many even went as far as taking photos of it to show their own kids. “It’s an archeology of time“ „... a journey into a time tunnel” “… a time capsule,” were only a few of their reactions. It was as if this was a testimony of a childhood which no longer existed.

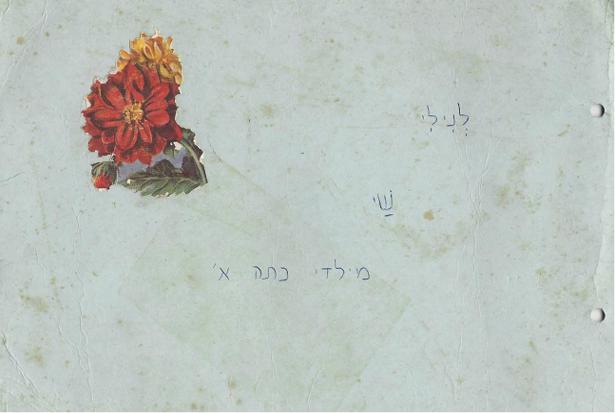

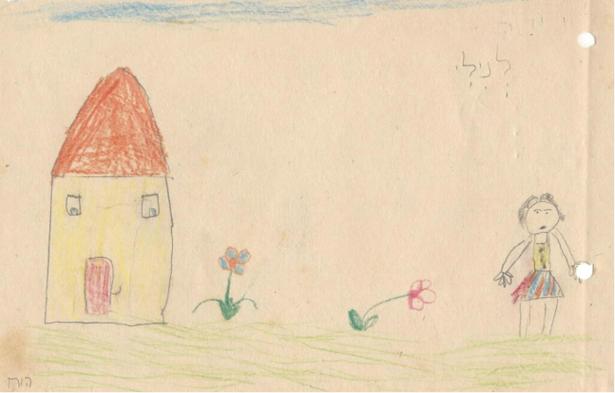

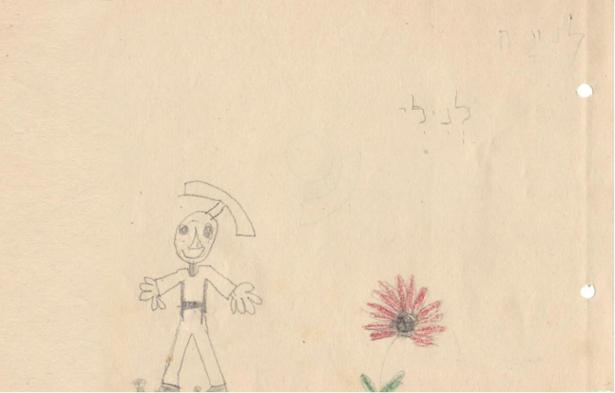

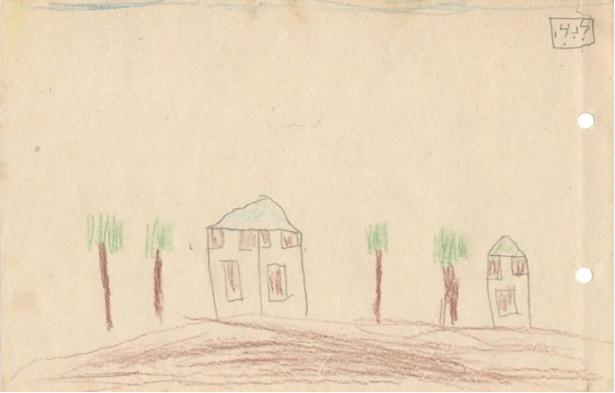

Here are a few examples from that booklet that caused so much interest at the school reunion:

To Nili—

A present to you from your First Grades class (written in the drawing)

It looks like children’s drawing haven’t changed much through the years, or even across decades. Isn’t this incredible?

I wish you all an exciting and pleasant read filled with curiosity and creativity!

“Wisdom is the daughter of experience.“

Leonardo Da Vinci

Chapter One

A look into art therapy

Art therapy is an instrument that aids us in expressing and communicating emotions. It combines the gaze of the distant observer, a view which represents insights and meanings—with the hand touching of the materials, which represents the sensory side sensuality and creativity. Through contact with concrete materials, such as different types of paints, clay, and various other materials, along with the presence of the therapist, a unique experience is created, one which enables the patient to express his own inner world using spontaneous images of the conscious and the subconscious.

Throughout the process of creation, the patient can express his early memories and pre-verbal experiences and put them into visual form – and, by doing so, he is able to make them more accessible and comprehensible. In this process, ambiguous thoughts can also become clearer. Creative work gives tangible shapes, colors and textures to feelings that have arisen and are now being revealed. During the process, it’s as though these works of art are almost asked to be expressed, created and seen. There’s a great deal of importance in the process of the expression itself, as well as to the visibility of the works and to their sharing. Later on, it’s also possible to come up with additional interpretations from analysis and processing of the drawings. In art therapy, sometimes emphasis is given to the creative process rather than to words. At other times, the observation process combines words and becomes a conversation about the meaning of the drawing.

Each detail in the process of creation holds a meaning. A seven year-old girl who came to therapy in order to build up her self-esteem, has drawn during this process on a larger piece of paper, which she had chosen herself. Suddenly, while drawing, she said, “I now have a bigger voice!” Even an allegedly minor detail such as the size of the paper on which she chose to drew influenced her and reflected on her sense of confidence and happiness.

Art therapy places huge importance on observing the patient and listening to his associations. This creates a major opportunity, one in which the therapist and the patient observe the work together and then discuss its meaning, (only in cases when the patient is interested in doing so). Such observations and conversations are held with adults and children alike.

The meaning and interpretation given to the drawings are complex, and there is more than one right answer. If, for one patient, the color green can represent growth, for another it can represent fear or jealousy. If, for one patient, the sun can be aggressive, threatening and burning, to another it can be soft, warm and caressing. Sometimes the two different options can be applicable to the very same patient; it’s possible—and advisable—to learn to live with opposite meanings that can occur in different situations.

Art therapy is very much about the reaction of the observer: an encouraging, validating observation, an observation which is devoid of any criticism or preaching, will influence the manner in which the child (or the adult) will draw. It will influence his ability to go on with the work or to abstain from working. Donald Winnicott writes about the great importance of this gaze, right from the beginning of infancy. He makes repeated observations on mothers and babies (in his book Playing and Reality) while asking: what does the baby see while looking into his mother’s face? These observations allowed Winnicott to come up with the insight that, according to him, what the baby sees when he gazes into his mother’s eyes is himself.

The gaze of the observer plays a great role in constructing the child’s sense of self. Additionally, the therapist (or any other kind of observer) observing the drawing, reflects the drawing toddler’s own sense of self, replicated in his drawing.

Heinz Kohut, the psychoanalyst and founder of the self psychology—a psychology that deals with the development of an ordinary sense of “self”—has emphasized in his writings (How Does Analysis Cure?) the child’s need for adoration as well as his need to adore, as a force that contributes to leading a creative life from a young age. This is a basic need in the process of healthy narcissism development, which, in essence, is the child’s ability to feel appreciated, valued and loved. The child needs the adoring and admiring reflection of the mother (when it is authentic).The authentic look of encouragement and joy on the observer’s part is the part of the process that deals with constructing a sense of security and vitality within the child, so that he can grow and carry this confidence within him.

The art therapist is skilled in observing in a manner which does not judge, but accepts and supports, as well as sowing enjoyment. Observing is a profound and complex process. When the observation benefits the patient during the creation process, his confidence will increase. Once he frees himself of thoughts such as, “This is what I needed (and wanted) to see,” and of his own judgment, the observation becomes more open. It’s at this point, that the patient begins to reveal more.

In this book, we will focus on a few basic principles of art therapy and will learn how to apply them onto our daily lives. We will learn and discover how every external change in the child’s doodling process is parallel to his own emotional occurrences, and how these two processes influence one another. With this understanding, parents are able to perceive more, and in turn react with authenticity and enthusiasm from the very first lines that the child doodles. The child will perceive this appreciative, non-judgmental and accepting observation as a reflection of support, validation and enthusiasm for him and his work. This authentic enthusiasm will enable parents to enjoy the moment—the way the child is drawing right now, at his current stage of his development—instead of the way we would like to see him draw in the future, once he is able to draw a figure, a house or any other defined shape. The purpose of the child’s drawing is not to satisfy the needs of the observer. The observing parent is welcome to join and accompany the child joyfully, hand in hand, travelling along the lines that are marked and created in the current moment.

This is a wonderful way for the parents to give their child a validation and make him feel appreciated and wanted. Therefore, the child will develop the motivation and ability to continue to create. These are valuable gifts for a meaningful life.

Chapter Two

“Scribbling,” drawing and self-esteem—how do they relate?

When I asked an acquaintance for a drawing by her two and a half year old, her response was: “But these are only scribbles.”

Is that so? Are scribbles really only scribbles?

The term “doodling,” which is a more professional name for scribbling, carries a very important meaning. It represents the beginning of the creative process, expresses the child’s own emotional development, and exposes their inner echoes, as the famous artist Wassily Kandinsky once said.

Doodling reflects situations in life. The more joyful and spontaneous the child’s doodle, the more his ability to translate his feelings and his thoughts will increase, and the correlation between his inner and external worlds will grow accordingly. Doodling enables one to express a relationship with the environment. It’s a vital form of expression and an incredible way to express emotions and the vitality and the richness of one’s inner world, even before the appearance of words. If one can understand the meaning of a doodle, one can also appreciate and value every line in it. In constructing such appreciation, respect for the child also deepens and he feels more understood. That way, his self-esteem will be increased, he will feel freer to express himself, more valued for who and what he is, and he will have more courage to explore and experiment. That way, he can continue to doodle and draw joyfully, and lay the groundwork for his own uniqueness.

Why are visual imagery, doodles, drawing and an encouraging reaction so important?

They enable us to experiment and provide us with a space for us to explore the question: “Who am I?” They enable us to feel happiness, fun, satisfaction and calmness. Through this process, the child is granted with a space where he can get to know his own abilities.

Drawings and doodles also allow us to express ourselves more freely, which gives us courage and confidence, and also an ability to rely on ourselves and build an independent identity. These are tools which contribute to the construction of high self-esteem.

In addition to that, doodling and drawing also open up a new, alternative space where we can grab a seat, observe and also be observed. It’s a place for us to express a variety of emotions; it’s a bridge between the internal and external world; a tool which helps us to know and enrich our world of imagination as well as our real, tangible world.

Drawing and doodling help us to improve the way we plan and organize, and also to improve our ability to persist and dedicate ourselves to one thing. They are wonderful tools which help us develop our ability to imagine and symbolize. They also improve the skills of expression and interpersonal communication, which is often a means of bringing parents (and other important figures in the child’s life) closer together with their children.

So, to the mothers who ask me, “Why doesn’t my child draw?” or “Why’s the paper on which he’s supposed to draw in kindergarten always blank?” I usually explain:

Doodling and drawing are processes that can occur naturally and intuitively in any place and in any way. The toddler may doodle on the beach or during playtime, or while eating porridge.

Children who “do not draw” have come to me for therapy more than once, and have begun to love and enjoy drawing. How did this happen? I didn’t do much. I “simply” listened to the drawing with no expectations and with great enjoyment in what the child brought. And it worked. The child began to draw happily and lovingly.

So why do children sometimes abstain from drawing on paper? Expectations. Drawing on paper might promote a greater expectation for results, expectations that the child receives from his environment, and influence his ability to produce results on the grounds of “performance anxiety.” It’s not unlikely that the same child, if he’d grown up in the jungle, or in any other place where the expectation for immediate results had not spoiled his toddler’s natural tendencies, then he would have been able to draw freely.

It is true that not all children are equal in their ability to draw and control their doodle. Children may demonstrate greater or lesser control, and some may even have development disorders, motor problems or attention deficit disorders (such disorders should be looked into), but what about love for the play itself? For creating for the sake of pure fun? In this book, we won’t deal with the differences in children’s abilities, but rather with the love for the play and the possibilities of creation, which are so important for the development of each and every one of us. Much like Erno Stern ,the pioneer of creative education says; the act of painting is an integral part of our needs as human beings—and it is an act that can be done by anyone and grants us incredible joy.

Chapter Three

The drawing, the “me” and the soul of the child:

changing and evolving together

In order to deepen the understanding and interest in children’s drawings, starting from the doodling stage, I will describe the development in children’s drawings and how this process is parallel to the child’s emotional growth. I will also focus on the changes which occur in drawings of children aged approximately one-and-a-half, once the child starts to draw shapes. I will try to explain the huge influence these two parallel processes have on the child’s emotional world.

Motor development, starting from the doodles, reflects the child’s process of emotional development, during which a sense of consistency, method and cohesion is formed within him – one which binds and collects his different experiences together. A sense of awareness of the existence of a separate self also begins to form within him, along with the construction of his own identity.

The French author, George Perec, wrote in his book, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, that in order to transfer from the personal realm of the self, into the public realm that pertains to the “other,” one is in need of a password, and simply cannot slide from one sphere to another. In order to do so, according to Perec, he would need to first cross the threshold, to communicate.