Полная версия

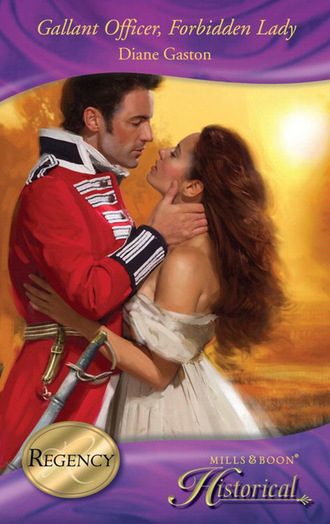

Gallant Officer, Forbidden Lady

He smiled inwardly. If she only knew how often emotion was his enemy, skirmishing with him even in this room.

Again her green eyes sought his. ‘Did you know the artist has another painting here?’ She took his arm. ‘Come. I will show you. You will be surprised.’

She led him to another corner of the room where, among all the great artists, she had discovered his other work.

‘See?’ She pointed to the painting of a British soldier raising the flag at Badajoz. ‘The one above the landscape. Of the soldier. Look at the emotions of relief and victory and fatigue on the soldier’s face.’ She opened her catalogue and scanned the pages. ‘Victory at Badajoz, it is called, and the artist is Jack Vernon.’ Her gaze returned to the painting. ‘What is so fascinating to me is that Vernon also hints at the amount of suffering the man must have endured to reach this place. Is that not marvellous?

‘You like this one, too, then?’ Jack could not have felt more gratified had the President of the Academy, Benjamin West himself, made the comment.

‘I do.’ She nodded emphatically.

He’d painted Victory at Badajoz to show that fleeting moment when it felt as if the siege of Badajoz had been worth what it cost. She had seen precisely what he’d wanted to convey.

Jack turned to her. ‘Do you know so much of soldiering?’

She laughed again. ‘Nothing at all, I assure you. But this is exactly how I would imagine such a moment to feel.’ She took his arm again. ‘Let me show you another.’

She led him to a painting the catalogue listed as The Surrender of Pamplona. Wellington, who only this month had become Duke of Wellington, was shown in Roman garb and on horseback accepting the surrender of the Spanish city of Pamplona, depicted in the painting as a female figure. The painting was stunningly composed and evocative of classical Roman friezes. Its technique was flawless.

‘You like this one, as well?’ he asked her. ‘It is well done. Very well done.’

She gave it a dismissive gesture. ‘It is ridiculous, Wellington in Roman robes!’

He smiled in amusement. ‘It is allegorical.’

She sent him a withering look. ‘I know it is allegorical, but do you not think it ridiculous to depict such an event as if it occurred in ancient Rome?’ Her gaze swung back to the painting. ‘Look at it. I do not dispute that it is well done, but it pales in comparison to the other painting of victory, does it not? Where is the emotion in this one?’

He examined the painting again, as she had demanded, but could not resist continuing the debate. ‘Is it not unfair to compare the two when the aim of each is so different? One is an allegory and the other a history painting.’

She made a frustrated sound and shook her head in dismay. ‘You do not understand me. I am saying that this artist takes all the meaning, all the emotion, away by making this painting an allegory. A victory in war must be an emotional event, can you not agree? The painting of Badajoz shows that. I much prefer to see how it really was.’

How it really was? If only she knew to what extent he had idealised that moment in Badajoz. He’d not shown the stone of the fortress slick with blood, nor the mutilated bodies, nor the agony of the dying.

He glanced back at his painting. He’d not deliberately set about depicting the emotion of victory in the painting of it. He’d meant only to show he could do more than paint portraits. With the war over, he supposed there might be some interest in military art. If someone wished him to paint a scene from a battle, he would do it, even if he must hide how it really was.

Jack glanced back at his painting and again at the allegory. Some emotion, indeed, had crept into his painting, emotion absent from the other.

He turned his gaze upon the woman. ‘I do see your point.’

She grinned in triumph. ‘Excellent.’

‘I cede to your expertise on the subject of art.’ He bowed.

‘Expertise? Nonsense. I know even less of art than of soldiering.’ Her eyes sparkled with mischief. ‘But that does not prevent me from expressing my opinion, does it?’

Jack was suddenly eager to identify himself to her, to let her know he was the artist she so admired. ‘Allow me to make myself known to you—’

‘Ariana!’ At that moment an older woman, also quite beautiful, rushed up to her. ‘I have been searching the rooms for you. There is someone you must meet.’

The young woman gave Jack an apologetic look as her companion pulled on her arm. ‘We must hurry.’

Jack bowed and the young woman made a hurried curtsy before being pulled away.

Ariana. Jack repeated the name in his mind, a name as lovely and unusual as its bearer.

Ariana.

Ariana Blane glanced back at the tall gentleman with whom she had so boldly spoken. She left him with regret, certain she would prefer his company to whomever her mother was so determined she should meet.

She doubted she would ever forget him, so tall, well formed and muscular. He wore his clothes so very well one could forget his coat and trousers were not the most fashionable. His face was strong, chiselled, solid, the face of a man one could depend upon to do what needed to be done. His dark hair was slightly tousled and in need of a trim, and the shadow of a beard was already evident in mid-afternoon. It gave him a rakish air that was quite irresistible.

But it was that fleeting moment of emotion she’d seen in him that had made her so brazenly decide to speak to him. She doubted anyone else would have noticed, but something had shaken him and he’d fought to overcome it. All in an instant.

When she approached him his eyes held her captive. As light a brown as matured brandy, they were unlike any she had seen before. They gave the impression that he had seen more of the world than he found bearable.

And that he could see more of her than she might wish to show.

She sighed. Such an intriguing man.

He had almost introduced himself when her mother interrupted. Ariana wished she’d discovered who he was. She was not in the habit of showing an interest in a man, but he had piqued her curiosity. Now she might never see him again.

Unless she managed to appear on stage, as she was determined to do. Perhaps he would see her perform and seek her out in the Green Room afterwards.

Her mother brought her over to a dignified-looking gentleman of compact build and suppressed energy. Her brows rose. He did not appear to be one of the ageing men of wealth to whom her mother persisted in introducing her. You would think her mother wished her to place herself under a gentleman’s protection rather than seek a career on the London stage.

Of course, her mother had been successful doing both and very likely had the same future in mind for her daughter.

‘Allow me to make you known to my daughter, Mr Arnold.’ Her mother gave her a tight smile full of warning that this introduction was important. ‘My daughter, Miss Ariana Blane.’

She needn’t have worried. Ariana recognised the name. She bestowed on Mr Arnold her most glittery smile and made a graceful curtsy. ‘Sir.’

‘Why, she is lovely, Daphne.’ Mr Arnold beamed. ‘Very lovely indeed.’

Her mother pursed her lips, not quite as pleased with Mr Arnold’s enthusiastic assessment as Ariana was. ‘Mr Arnold manages the Drury Lane Theatre, dear.’

‘An explanation is unnecessary, Mama.’ Ariana took a step forwards. ‘Everyone in the theatre knows who Mr Arnold is. I am greatly honoured to meet you, sir.’ She extended her hand to him.

He clasped her fingers. ‘And I, you, Miss Blane.’

Ariana inclined her head towards him. ‘I believe you have breathed new life into the theatre with your remarkable Edmund Kean.’

Edmund Kean’s performance of Shylock in The Merchant of Venice had been a sensation, critically acclaimed far and wide.

The man smiled. ‘Did you see Kean’s performance?’

‘I did and was most impressed,’ Ariana responded.

‘You saw the performance?’ Her mother looked astonished. ‘I did not know you had been in London.’

Ariana turned to her. ‘A few of us came just to see Kean. There was no time to contact you. We returned almost immediately lest we miss our own performance.’

Arnold continued without heeding the interruption. ‘Your mother has informed me that you are an actress.’

Ariana smiled. ‘Of course I am! What else should the daughter of the famous Daphne Blane be but an actress? It is in my blood, sir. It is my passion.’

He nodded with approval. ‘You have been with a company?’

‘The Fisher Company.’

‘A very minor company,’ her mother said.

‘I am acquainted with Mr Fisher.’ Mr Arnold appeared impressed.

Four years ago, when Ariana had just turned eighteen, she’d accepted a position teaching poetry at the boarding school in Bury St Edmunds she’d attended since age nine. She’d thought she had no other means of making a life for herself. At the time her mother had a new gentleman under her roof, and would not have welcomed Ariana’s return. Fate intervened when the Fisher Company came to the town to perform Blood Will Have Blood at the Theatre Royal, and Ariana attended the performance.

The play could not have been more exciting, complete with storm, shipwreck, horses and battle. The next day Ariana packed up her belongings, left the school, and sought out Mr Fisher, begging for a chance to join the company. She knew he hired her only because she was the famous Daphne Blane’s daughter, but she did not care. Ariana had found the life she wanted to live.

‘What have you performed?’ Mr Arnold asked her.

‘My heavens, too many to count. I was with the company for four years.’

With the Fisher Company she’d performed in a series of hired barns and small theatres in places like Wells-next-the-Sea and Lowestoft, but she had won better parts as her experience grew.

She considered her answer. ‘Love’s Frailties, She Stoops to Conquer, The Rivals.’ She made certain to mention The Rivals, knowing its author, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, still owned the Drury Lane Theatre.

Her mother added, ‘Mere comedies of manners, and some of her roles were minor ones.’

‘Oh, but I played Lucy in The Rivals.’ Ariana glanced at her mother. Why had she insisted upon her meeting Mr Arnold only to thwart every attempt Ariana made to impress the man?

‘Tell me,’ Mr Arnold went on, paying heed to Ariana and ignoring the famous Daphne Blane, ‘have you played Shakespeare?’

‘The company did not perform much Shakespeare,’ Ariana admitted. ‘I did play Hippolyta in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Why do you ask, sir?’

Mr Arnold leaned towards her in a conspiratorial manner. ‘I am considering a production of Romeo and Juliet, to capitalise on the success of Kean. If I am able to find the financing for it, that is.’

Ariana’s mother placed her hand on Arnold’s arm. ‘Will Kean perform?’

He patted her hand. ‘He will be asked, I assure you, but even if he cannot, a play featuring Daphne Blane and her daughter should be equally as popular.’

Her mother beamed at the compliment. ‘That is an exciting prospect.’

Arnold nodded. ‘Come to the theatre tomorrow, both of you, and we will discuss it.’

‘We will be there,’ her mother assured him.

He bowed and excused himself.

Ariana watched him walk away, her heart racing in excitement. She might perform at the Drury Lane Theatre on the same stage as Edmund Kean, the same stage as her mother.

Hoping for another glance at Ariana, Jack wandered around the room now, only pretending to look at the paintings.

Could he approach her? What would he say? I am the artist whose work you admired. He did want her to know.

The war’s demons niggled at him again as he meandered through the crowd. He forced himself to listen to snippets of conversations about the paintings, but it was not enough. He needed to see her again.

On his third walk around the room, he found her. She and the woman who’d snatched her from his side now conversed with an intense-looking gentleman. Jack’s Ariana seemed quite animated in her responses to the man, quite pleased to be speaking to him. Even from this distance he could feel the power of her smile, see the sparkle in her eyes.

When the man took leave of them, the older woman walked Ariana over to two aristocratic-looking gentlemen. Ariana did not seem as pleased to be conversing with these gentlemen as she had with the intense-looking fellow, but it was clear to Jack he could devise no further encounter with her.

He backed away and returned to examining the paintings, this time assessing them for the presence or absence of emotion.

Someone clapped him on the shoulder. ‘Well, my boy. How does it feel to have your work hanging in Somerset House?’

It was his mentor, Sir Cecil.

‘It is a pleasure unlike any I have ever before experienced, my good friend, and I have you to thank for it.’ Jack shook the man’s hand. ‘I did not expect you in London. I am glad to see you.’

Sir Cecil strolled with him back to the spot in the room where Nancy’s portrait hung. ‘Had to come, my boy. Had to come.’ He gazed up at the portrait. ‘This is fine work. Its place here is well deserved. Unfortunate your sister cannot see her portrait hanging in such honour.’

‘She has seen it,’ Jack responded. ‘She is here. She and my mother. They are this moment repairing a tear in my mother’s gown. They should return soon.’

‘I am astonished.’ Sir Cecil blinked. ‘It is unlike your mother to come to London, is it not?’

His mother had not been in London since his father died, so many years ago. ‘She wished to be here for this, I think.’

That was only part of the reason. The truth was, his mother had come to London because Tranville, the man who’d made her his mistress, had also come to town.

When Jack’s father, the nephew of an earl, had been an officer in the Life Guards, the whole family lived in London. John and Mary Vernon were accepted everywhere, and Jack could remember them dressed in finery, ready for one ball or another. All that changed with his father’s death. Suddenly there were too many debts to pay and not enough money to pay them. Jack’s mother moved them to Bath where Tranville took notice of the pretty young widow and put her under his protection.

Jack’s mother always insisted Tranville had been the family’s salvation, but as Jack got older, he realised she could have appealed to his father’s uncle. The earl would not have allowed them to starve. Once his mother chose Tranville and abandoned all respectability, his great-uncle washed his hands of them.

Sir Cecil patted Jack on the arm. ‘It is good your mother and sister have come. How long do they stay?’

Jack shrugged. ‘It depends.’

Depends upon how long Tranville remained in London, Jack suspected. Jack’s mother was a foolish woman. Tranville had been no more faithful to her than he’d been to his own wife. He did return to her from time to time, between other conquests.

Matters were different now. Tranville had unexpectedly inherited a barony and become even more wealthy than before. Shortly thereafter, his wife died. Since suddenly becoming a rich, titled and eligible widower, he’d not called upon Jack’s mother at all. There was no reason to expect him to do so while she was in London.

Jack cleared his throat. ‘My mother and sister have taken rooms on Adam Street, a few doors from my studio.’

‘You have established a studio?’ Sir Cecil beamed with approval. ‘Excellent, my boy.’

Tranville’s money paid for his mother’s rooms. Practically every penny she possessed came from him. He had thus far kept his promise to support her for life. His money had kept her and her children in great comfort. It had paid for Jack’s education and his commission in the army. Jack swore he would pay that money back some day.

‘The studio is not much,’ Jack admitted to Sir Cecil. ‘Little more than a room to paint and a room to sleep, but the light is good.’

‘And the address is acceptable,’ added the older man, thoughtfully.

The address was not prestigious, but it was an area of town near both Covent Garden and the Adelphi Buildings, which attracted respectable residents.

‘I should like to see it,’ Sir Cecil said. ‘And to call upon your mother. I am in London for a few weeks. My son, you know, is studying architecture here at the Academy.’

‘I hope to see you both, then.’ Jack spied his mother and sister searching through the crowd. ‘One moment, sir. My mother and Nancy approach.’

Nancy caught sight of him and waved. She led their mother to where Jack stood. Sir Cecil greeted them warmly.

‘Jack.’ Nancy’s eyes sparkled with excitement. ‘I cannot tell you how many people have asked me if I am the young lady in your portrait. I told them all the direction of your studio.’

His mother lifted her eyebrows. ‘I would say some of those enquiries were from very impertinent gentlemen.’

Jack straightened and glanced around the room.

‘Do not get in a huff, Brother.’ Nancy laughed. ‘I came to no harm. It was mere idle curiosity on their part, I am certain.’

Jack was not so certain. He worried about Nancy in London. With her dark hair, fair complexion and bright blue eyes, she was indeed as fresh and lovely as the incomparable Ariana had said. Jack worried about Nancy’s future even more. What chance did she have to meet eligible gentlemen? What sort of man would marry the dowerless daughter of a kept woman?

He frowned.

His mother touched his arm. ‘I confess to being fatigued, my son. How much longer do you wish to stay?’

He glanced around the room. The crowd was suddenly thinning. The afternoon had grown late and many of those in attendance would be heading to their townhouses in May fair. Some of them, perhaps, would take their carriages for a turn in Hyde Park before returning home. It was the fashionable hour to ride through the park.

Jack, his mother, and sister would walk to Adam Street.

‘We may leave now, if you like.’ Jack glanced around the room again, hoping for one more glimpse of Ariana.

Luck was with him when he and Sir Cecil escorted his mother and sister to the door. Ariana appeared a few steps ahead, but there was no question of approaching her. She and her companion walked with two wealthy-looking and attentive gentlemen.

Jack pushed aside his flash of envy. Instead, he focused on the way she carried herself, the graceful nature of her walk. He watched how her pale pink gown swirled about her legs with each step, how the blue shawl draped around her shoulders moved with each sway of her hips.

Jack watched her as they reached the outside and crossed the courtyard. No more than five feet behind her, he might as well have been a mile. Her party continued to the Strand where a line of carriages waited. In a moment Jack would have to head towards home. This would be his last glimpse of her.

She turned and caught sight of him. Her face lit up and took his breath away. His gaze locked with hers, and he thought he sensed the same regret in her eyes that was gnawing at his insides.

One of the gentlemen accompanying her took her arm. ‘The carriage, my dear,’ he said in a proprietary tone, apparently unaware of Jack staring at her.

She turned back one more time and found him again. ‘Goodbye,’ she mouthed before being assisted into a shiny, elegant barouche.

Jack watched her until he could see the barouche no more. He tried to engrave her image upon his memory but could feel it fading with each moment. He needed to reach his studio. He needed paper and pencil. He needed to draw her before the image was lost to him as well.

Chapter Two

London—January 1815

This chilly January night, Jack escorted his mother and sister to the theatre. His latest commission, a wealthy banker, offered Jack the use of his box to see Edmund Kean in Romeo and Juliet.

Jack had acquired some good commissions because of the exhibition, until the oppressive heat of August drove most of the wealthy from London. The banker, Mr Slayton, was his final one. Jack’s mother and sister also returned to Bath, but they came back to London with the new year. Jack had placed an advertisement seeking some fresh commissions in the Morning Post, but, thus far, no one had answered it.

Jack tried to set his financial worries aside as he assisted his mother to her seat in the theatre box. Sir Cecil’s son, Michael, was also in their company attending Jack’s sister. Michael, as kind-faced as his father, but tall, dark-haired and slim, continued with his architectural studies and had again become a frequent addition to Jack’s mother’s dinner table now that she and Nancy were back in London.

As Nancy took her seat, it was clear she was already enjoying herself. ‘It is so beautiful from up here.’

They’d attended the theatre once the previous summer, but sat on the orchestra floor with the general admission. From the theatre box the rich reds and gleaming golds of the décor were displayed in all their splendour.

Nancy turned to Jack. ‘Thank you so much for bringing us.’

He was glad she was pleased. ‘You should thank Mr Slayton for giving me the tickets.’

‘Oh, I do.’ She turned to their mother. ‘Perhaps we should write him a note of gratitude.’

‘We shall do precisely that,’ her mother agreed.

‘Well, I am grateful, as well.’ Michael stood gazing out at the house. ‘This is a fine building.’

Nancy left her chair to stand beside him. ‘You will probably gaze all evening at the arches and ceiling and miss the play entirely.’

He grinned. ‘I confess they will distract me.’

She gave an exaggerated sigh. ‘But the play is Romeo and Juliet. How can you think of a building when you shall see quite possibly the most romantic play ever written?’

He laughed. ‘Miss Vernon, I could try to convince you that beautiful arches and elegant columns are romantic, but I suspect you will never agree with me.’

‘I am certain I will not.’ She nodded.

‘I remember coming here in my first Season.’ Jack’s mother spoke in a wistful tone. ‘Of course, that was the old theatre. There were not so many boxes in that auditorium.’

That Drury Lane Theatre burned down in 1809.

Nancy surveyed the crowd. ‘There are many grand people here.’

The play was quite well attended, even though most of the beau monde would not come to London for another month or so. Perhaps Jack’s commissions would increase then. Of course, with the peace, many people had chosen to travel to Paris or Vienna and would not be in London at all. Still, the theatre had an impressive crowd. Edmund Kean had been drawing audiences all year in a series of Shakespearean plays.

Nancy leaned even further over the parapet. ‘Mama, I see Lord Tranville.’

‘Do you?’ Jack’s mother’s voice rose an octave.

‘There.’ Nancy stepped aside so her mother could see. ‘The third balcony. Near the stage.’

‘I believe you are correct.’ Her voice was breathless.

Tranville stood with another gentleman in a box close to the stage, the two men in conversation while surveying the theatre. If Tranville spied his former mistress in the crowd, he made no show of it.

The curtain rose and Nancy and Michael sat in their chairs. Nancy’s gaze was riveted to the stage, but their mother’s drifted to the nearby box where Tranville sat.

Jack’s jaw flexed.

Edmund Kean walked on.

‘He is old!’ Nancy whispered.

Shakespeare had written Romeo as a young man who falls in love as only a young man could. Kean’s youth was definitely behind him. Still, Kean made an impressive figure in the costume of old Verona, moving about the stage in a dramatic manner. It would be a challenge to capture that movement in oils, Jack thought.