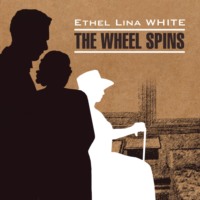

Полная версия

Колесо крутится. Леди исчезает / The Wheel Spins. The Lady Vanishe

“Handsome pair,” he said in an approving voice.

“I wonder who they really are,” remarked Miss Flood-Porter. “The man’s face is familiar to me. I know I’ve seen him somewhere.”

“On the pictures, perhaps,” suggested her sister.

“Oh, do you go?” broke in Mrs. Barnes eagerly, hoping to claim another taste in common, for she concealed a guilty passion for the cinema.

“Only to see George Arliss and Diana Wynyard,” explained Miss Flood-Porter.

“That settles it,” said the vicar. “He’s certainly not George Arliss, and neither is she Diana.”

“All the same, I feel certain there is some mystery about them,” persisted Miss Flood-Porter.

“So do I,” agreed Mrs. Barnes. “I–I wonder if they are really married.”

“Are you?” asked her husband quickly.

He laughed gently when his wife flushed to her eyes.

“Sorry to startle you, my dear,” he said, “but isn’t it simpler to believe that we are all of us what we assume to be? Even parsons and their wives.” He knocked the ashes out of his pipe, and rose from his chair. “I think I’ll stroll down to the village for a chat with my friends.”

“How can he talk to them when he doesn’t know their language?” demanded Miss Rose bluntly, when the vicar had gone from the garden.

“Oh, he makes them understand,” explained his wife proudly. “Sympathy, you know, and common humanity. He’d rub noses with a savage.”

“I’m afraid we drove him away by talking scandal,” said Miss Flood-Porter.

“It was my fault,” declared Mrs. Barnes. “I know people think I’m curious. But, really, I have to force myself to show an interest in my neighbour’s affairs. It’s my protest against our terrible national shyness.”

“But we’re proud of that,” broke in Miss Rose. “England does not need to advertise.”

“Of course not… But we only pass this way once. I have to remind myself that the stranger sitting beside me may be in some trouble and that I might be able to help.”

The sisters looked at her with approval. She was a slender woman in the mid-forties, with a pale oval face, dark hair, and a sweet expression. Her large brown eyes were both kind and frank – her manner sincere.

It was impossible to connect her with anything but rigid honesty. They knew that she floundered into awkward explanations, rather than run the risk of giving a false impression.

In her turn, she liked the sisters. They were of solid worth and sound respectability. One felt that they would serve on juries with distinction, and do their duty to their God and their neighbour – while permitting no direction as to its nature.

They were also leisured people, with a charming house and garden, well-trained maids and frozen assets in the bank. Mrs. Barnes knew this, so, being human, it gave her a feeling of superiority to reflect that the one man in their party was her husband.

She could appreciate the sense of ownership, because, up to her fortieth birthday, she had gone on her yearly holiday in the company of a huddle of other spinsters. Since she had left school, she had earned her living by teaching, until the miracle happened which gave her – not only a husband – but a son.

Both she and her husband were so wrapped up in the child that the vicar sometimes feared that their devotion was tempting Fate. The night before they set out on their holiday he proposed a pact.

“Yes,” he agreed, looking down at the sleeping boy in his cot. “He is beautiful. But… It is my privilege to read the Commandments to others. Sometimes, I wonder—”

“I know what you mean,” interrupted his wife. “Idolatry.”

He nodded.

“I am as guilty as you,” he admitted. “So I mean to discipline myself. In our position, we have special opportunities to influence others. We must not grow lop-sided, but develop every part of our nature. If this holiday is to do us real good, it must be a complete mental change… My dear, suppose we agree not to talk exclusively of Gabriel, while we are away?”

Mrs. Barnes agreed. But her promise did not prevent her from thinking of him continually. Although they had left him in the care of a competent grandmother, she was foolishly apprehensive about his health.

While she was counting the remaining hours before her return to her son, and Miss Flood-Porter smiled in anticipation of seeing her garden, Miss Rose was pursuing her original train of thought. She always ploughed a straight furrow, right to its end.

“I can’t understand how any one can tell a lie,” she declared. “Unless, perhaps, some poor devil who’s afraid of being sacked. But – people like us. We know a wealthy woman who boasts of making false declarations at the Customs. Sheer dishonesty.”

As she spoke, Iris appeared at the gate of the hotel garden. She did her best to skirt the group at the table, but she could not avoid hearing what was said.

“Perhaps I should not judge others,” remarked Mrs. Barnes in the clear carrying voice of a form-mistress. “I’ve never felt the slightest temptation to tell a lie.”

“Liar,” thought Iris automatically.

She was in a state of utter fatigue, which bordered on collapse. It was only by the exercise of every atom of willpower that she forced herself to reach the hotel. The ordeal had strained her nerves almost to breaking-point. Although she longed for the quiet of her room, she knew she could not mount the stairs without a short rest. Every muscle felt wrenched as she dropped down on an iron chair and closed her eyes.

“If any one speaks to me, I’ll scream,” she thought.

The Misses Flood-Porter exchanged glances and turned down the corners of their mouths. Even gentle Mrs. Barnes’ soft brown eyes held no welcome, for she had been a special victim of the crowd’s bad manners and selfishness.

They behaved as though they had bought the hotel and the other guests were interlopers, exacting preferential treatment – and getting it – by bribery. This infringement of fair-dealing annoyed the other tourists, as they adhered to the terms of their payment to a travelling agency, which included service.

The crowd monopolised the billiard-table and secured the best chairs. They were always served first at meals; courses gave out, and bath-water ran luke-warm.

Even the vicar found that his charity was strained. He did his best to make allowance for the animal spirits of youth, although he was aware that several among the party could not be termed juvenile.

Unfortunately, Iris’ so-called friends included two persons who were no testimonial for the English nation; and since it was difficult to distinguish one girl in a bathing-brief from another, Mrs. Barnes was of the opinion that they were all doing the same thing – getting drunk and making love.

Her standard of decency was offended by the sun-bathing – her nights disturbed by noise. Therefore she was specially grateful for the prospect of two peaceful days, spent amid glorious scenery and in congenial company.

But, apparently, there was not a complete clearance of the crowd; there was a hangover, in this girl – and there might be others. Mrs. Barnes had vaguely remarked Iris, because she was pretty, and had been pursued by a bathing-gentleman with a matronly figure.

As the man was married, his selection was not to her credit. But she seemed to be so exhausted that Mrs. Barnes’ kindly heart soon reproached her for lack of sympathy.

“Are you left all alone?” she called, in her brightest tones.

Iris shuddered at the unexpected overture. At that moment the last thing in the world she wanted was mature interest, which, in her experience, masked curiosity.

“Yes,” she replied.

“Oh, dear, what a shame. Aren’t you lonely?”

“No.”

“But you’re rather young to be travelling without friends. Couldn’t any of your people come with you?”

“I have none.”

“No family at all?”

“No, and no relatives. Aren’t I lucky?”

Iris was not near enough to hear the horrified gasp of the Misses Flood-Porter; but Mrs. Barnes’ silence told her that her snub had not miscarried. To avoid a further inquisition, she made a supreme effort to rise, for she was stiffening in every joint, and managed to drag herself into the hotel and upstairs to her room.

Mrs. Barnes tried to carry off the incident with a laugh.

“I’m afraid I’ve blundered again,” she said. “She plainly resented me. But it seemed hardly human for us to sit like dummies, and show no interest in her.”

“Is she interested in you?” demanded Miss Rose. “Or in us? That sort of girl is utterly selfish. She wouldn’t raise a finger, or go an inch out of her way, to help any one.”

There was only one answer to the question, which Mrs. Barnes was too kind to make. So she remained silent, since she could not tell a lie.

Neither she – nor any one else – could foretell the course of the next twenty-four hours, when this girl – standing alone against a cloud of witnesses – would endure such anguish of spirit as threatened her sanity, on behalf of a stranger for whom she had no personal feeling.

Or rather – if there was actually such a person as Miss Froy.

Chapter four. England calling

Because she had a square on her palm, which, according to a fortune-teller, signified safety, Iris believed that she lived in a protected area. Although she laughed at the time, she was impressed secretly, because hers was a specially sheltered life.

At this crisis, the stars, as usual, seemed to be fighting for her. The mountains had sent out a preliminary warning. During the evening, too, she received overtures of companionship, which might have delivered her from mental isolation.

Yet she deliberately cut every strand which linked her with safety, out of mistaken loyalty to her friends.

She missed them directly she entered the lounge, which was silent and deserted. As she walked along the corridor, she passed empty bedrooms, with stripped beds and littered floors. Mattresses hung from every window and the small verandas were heaped with pillows.

It was not only company which was lacking, but moral support. The crowd never troubled to change for the evening, unless comfort suggested flannel trousers. On one occasion, it had achieved the triumph of a complaint, when a lady appeared at dinner dressed in her bathing-slip.

The plaintiffs had been the Misses Flood-Porter, who always wore expensive but sober dinner-gowns. Iris remembered the incident, when she had finished her bath. Although slightly ashamed of her deference to public opinion, she fished from a suitcase an unpacked afternoon frock of crinkled crêpe.

The hot soak and rest had refreshed her, but she felt lonely, as she leaned over the balustrade. Her pensive pose and the graceful lines of her dress arrested the attention of the bridegroom – Todhunter, according to the register – as he strolled out of his bedroom.

He had not the least knowledge of her identity, or that he had acted as a sort of guiding-star to her, in the gorge. He and his wife took their meals in their private sitting-room and never mingled with the crowd. He concluded, therefore, that she was an odd guest whom he had missed in the general scramble.

Approving her with an experienced eye, he stopped.

“Quiet, to-night,” he remarked. “Refreshing change after the din of that horrible rabble.”

To his surprise, the girl looked coldly at him.

“It is quiet,” she said. “But I happen to miss my friends.”

As she walked downstairs she felt defiantly glad that she had made him realise his blunder. Championship of her friends mattered more than the absence of social sense. But, in spite of her triumph, the incident was vaguely unpleasant.

The crowd had gloried in its unpopularity, which seemed to it a sign of superiority. It frequently remarked in complacent voices, “We’re not popular with these people,” or “They don’t really like us.” Under the influence of its mass-hypnotism, Iris wanted no other label. But now that she was alone, it was not quite so amusing to realise that the other guests, who were presumably decent and well-bred, considered her an outsider.

Her mood was bleakly defiant when she entered the restaurant. It was a big bare room, hung with stiff deep-blue wallpaper, patterned with conventional gilt stars. The electric lights were set in clumsy wrought-iron chandeliers, which suggested a Hollywood set for a medieval castle. Scarcely any of the tables were laid, and only one waiter drooped at the door.

In a few days, the hotel would be shut up for the winter. With the departure of the big English party, most of the holiday staff had become superfluous and had already gone back to their homes in the district.

The remaining guests appeared to be unaffected by the air of neglect and desolation inseparable from the end of the season. The Misses Flood-Porter shared a table with the vicar and his wife. They were all in excellent spirits and gave the impression of having come into their own, as they capped each other’s jokes, culled from Punch.

Iris pointedly chose a small table in a far corner. She smoked a cigarette while she waited to be served. The others were advanced in their meal and it was a novel sensation for one of the crowd to be in arrears.

Mrs. Barnes, who was too generous to nurse resentment for her snub, looked at her with admiring eyes.

“How pretty that girl looks in a frock,” she said.

“Afternoon frock,” qualified Miss Flood-Porter. “We always make a point of wearing evening dress for dinner, when we’re on the Continent.”

“If we didn’t dress, we should feel we were letting England down,” explained the younger sister.

Although Iris spun out her meal to its limit, she was driven back ultimately to the lounge. She was too tired to stroll and it was early for bed. As she looked round her, she could hardly believe that, only the night before, it had been a scene of continental glitter and gaiety – although the latter quality had been imported from England. Now that it was no longer filled with friends, she was shocked to notice its tawdry theatrical finery. The gilt cane chairs were tarnished, the crimson plush upholstery shabby.

A clutter of cigarette stubs and spent matches in the palm pots brought a lump to her throat. They were all that remained of the crowd.

As she sat apart, the vicar – pipe in mouth – watched her with a thoughtful frown. His clear-cut face was both strong and sensitive, and an almost perfect blend of flesh and spirit. He played rough football with the youths of his parish, and, afterwards, took their souls by assault; but he had also a real understanding of the problems of his women-parishioners.

When his wife told him of Iris’ wish for solitude, he could enter into her feeling, because, sometimes, he yearned to escape from people and even from his wife. His own inclination was to leave her to the boredom of her own company; yet he was touched by the dark lines under her eyes and her mournful lips.

In the end, he resolved to ease his conscience at the cost of a rebuff. He knew it was coming, because, as he crossed the lounge, she looked up quickly, as though on guard.

“Another,” she thought.

From a distance she had admired the spirituality of his expression; but, to-night, he was numbered among her hostile critics.

“Horrible rabble.” The words floated into her memory, as he spoke to her.

“If you are travelling back to England alone, would you care to join our party?”

“When are you going?” she asked.

“Day after to-morrow, before they take off the last through train of the season.”

“But I’m going to-morrow. Thanks so much.”

“Then I’ll wish you a pleasant journey.”

The vicar smiled faintly at her lightning decision as he crossed to a table and began to address luggage-labels.

His absence was his wife’s opportunity. In her wish not to break her promise, she had gone to the other extreme and had not mentioned her baby to her new friends, save for one casual allusion to “our little boy.” But, now that the holiday was nearly over, she could not resist the temptation of showing his photograph, which had won a prize in a local baby competition.

With a guilty glance at her husband’s back she drew out of her bag a limp leather case.

“This is my large son,” she said, trying to hide her pride.

The Misses Flood-Porter were exclusive animal-lovers and not particularly fond of children. But they said all the correct things with such well-bred conviction that Mrs. Barnes’ heart swelled with triumph.

Miss Rose, however, switched off to another subject directly the vicar returned from the writing-table.

“Do you believe in warning dreams, Mr. Barnes?” she asked. “Because, last night, I dreamed of a railway smash.”

The question caught Iris’ attention and she strained to hear the vicar’s reply.

“I’ll answer your question,” he said, “if you’ll first answer mine. What is a dream? Is it stifled apprehension—”

“I wonder,” said a bright voice in Iris’ ear, “I wonder if you would like to see the photograph of my little son, Gabriel?”

Iris realised dimly that Mrs. Barnes – who was keeping up England in limp brown lace – had seated herself beside her and was showing her the photograph of a naked baby.

She made a pretence of looking at it while she tried to listen to the vicar.

“Gabriel,” she repeated vaguely.

“Yes, after the Archangel. We named him after him.”

“How sweet. Did he send a mug?”

Mrs. Barnes stared incredulously, while her sensitive face grew scarlet. She believed that the girl had been intentionally profane and had insulted her precious little son, to avenge her boredom. Pressing her trembling lips together she rejoined her friends.

Iris was grateful when the humming in her ears ceased. She was unaware of her slip, because she had only caught a fragment of Mrs. Barnes’ explanation. Her interest was still held by the talk of presentiments.

“Say what you like,” declared Miss Rose, sweeping away the vicar’s argument, “I’ve common sense on my side. They usually try to pack too many passengers into the last good train of the season. I know I’ll be precious glad when I’m safely back in England.”

A spirit of apprehension quivered in the air at her words.

“But you aren’t really afraid of an accident?” cried Mrs. Barnes, clutching Gabriel’s photograph tightly.

“Of course not.” Miss Flood-Porter answered for her sister. “Only, perhaps we feel we’re rather off the beaten track here, and so very far from home. Our trouble is we don’t know a word of the language.”

“She means,” cut in Miss Rose, “we’re all right over reservations and coupons, so long as we stick to hotels and trains. But if some accident happened to make us break our journey, or lose a connection, and we were stranded in some small place, we should feel lost. Besides it would be awkward about money. We didn’t bring any travellers’ cheques.”

The elder sister appealed to the vicar.

“Do you advise us to take my sister’s dream as a warning and travel back to-morrow?”

“No, don’t,” murmured Iris under her breath.

She waited for the vicar’s answer with painful interest, for she was not eager to travel on the same train as these uncongenial people, who might feel it their duty to befriend her.

“You must follow your own inclinations,” said the vicar. “But if you do leave prematurely, you will not only give a victory to superstition, but you will deprive yourself of another day in these glorious surroundings.”

“And our reservations, are for the day after to-morrow,” remarked Miss Rose. “We’d better not risk any muddles…And now, I’m going up to pack for my journey back to dear old England.”

To the surprise of everyone her domineering voice suddenly blurred with emotion. Miss Flood-Porter waited until she had gone out of the lounge, before she explained.

“Nerves. We had a very trying experience, just before we came away. The doctor ordered a complete change so we came here, instead of Switzerland.”

Then the innkeeper came in, and, as a compliment to his guests, fiddled with his radio, until he managed to get London on the long wave. Amid a machine-gun rattle of atmospherics, a familiar mellow voice informed them, “You have just been listening to…”

But they had heard nothing.

Miss Flood-Porter saw her garden, silvered by the harvest moon. She wondered whether the chrysanthemum buds, three to a pot, were swelling, and if the blue salvias had escaped the slugs.

Miss Rose, briskly stacking shoes in the bottom of a suitcase, quivered at a recollection. Again she saw a gaping hole in a garden-bed, where overnight had stood a cherished clump of white delphiniums… It was not only the loss of their treasure, but the nerve-racking ignorance of where the enemy would strike next…

The Vicar and his wife thought of their baby, asleep in his cot. They must decide whether they should merely peep at him, or risk waking him with a kiss.

Iris remembered her friends in the roaring express, and was suddenly smitten with a wave of home-sickness.

England was calling.

Chapter five. The night express

Iris was awakened that night, as usual, by the express screaming through the darkness. Jumping out of bed, she reached the window in time to see it outline the curve of the lake with a fiery wire. As it rattled below the hotel, the golden streak expanded to a string of lighted windows, which, when it passed, snapped together again like the links of a bracelet.

After it had disappeared round the gorge, she followed its course by its pall of quivering red smoke. In imagination, she saw it shooting through Europe, as though it were an explosive shuttle ripping through the scorched fabric of the map. It caught up cities and threaded them on a gleaming whistling string. Illuminated names flashed before her eyes and were gone – Bucharest, Zagreb, Trieste, Milan, Basle, Calais.

Once again she was flooded with home-hunger, even though her future address were an hotel. Mixed with it was a gust of foreboding – which was a legacy from the mountains.

“Suppose – something – happened, and I never came back.”

At that moment she felt that any evil could block the way to her return. A railway crash, illness, or crime were possibilities, which were actually scheduled in other lives. They were happening all round her and at any time a line might give way in the protective square in her palm.

As she lay and tossed, she consoled herself with the reminder that this was the last time she would lie under the lumpy feather bed. Throughout the next two nights she, too, would be rushing through the dark landscape, jerked out of every brief spell of sleep by the flash of lights, whenever the express roared through a station.

The thought was with her when she woke, the next morning, to see the silhouette of mountain-peaks iced against the flush of sunrise.

“I’m going home to-day,” she told herself exultantly.

The air was raw when she looked out of her window. Mist was rising from the lake which gleamed greenly through yellowed fans of chestnut trees. But in spite of the blue and gold glory of autumn she felt indifferent to its beauty.

She was also detached from the drawbacks of her room, which usually offended her critical taste. Its wooden walls were stained a crude shade of raw sienna, and instead of running water there was a battered washstand which bore a tin can, covered with a thin towel.

In spirit, Iris had already left the hotel. Her journey was begun before she started. When she went down to the restaurant she was barely conscious of the other guests, who, only a few hours before, had inspired her with antipathy.

The Misses Flood-Porter, who were dressed for writing letters in the open, were breakfasting at a table by the window. They did not speak to her, although they would have bowed as a matter of courtesy, had they caught her eye.

Iris did not notice the omission, because they had gone completely out of her life. She drank her coffee in a silence which was broken by occasional remarks from the sisters, who wondered whether the English weather were kind for a local military wedding.

Her luck held, for she was spared contact with the other guests, who were engrossed by their own affairs. As she passed the bureau, Mrs. Barnes was calling a waiter’s attention to a letter in one of the pigeon-holes. Her grey jersey-suit, as well as her packet of sandwiches, advertised an excursion.

The vicar, who was filling his pipe on the veranda, was also in unconventional kit – shorts, sweater, nailed boots, and the local felt hat – adorned with a tiny blue feather – which he had bought as a souvenir of his holiday.