Полная версия

With the End in Mind

The lesson was coming home to me. Those bereavement conversations are just the beginning, the start of a process that is going to take a lifetime for people to live alongside in a new way. I wondered how many others would have called, had I given them a name and a number in writing. By now I was more aware of the network of care that is available, and I asked Irene’s husband for permission to contact his GP. I told him I was honoured that he felt he could call me. I told him that I remembered Irene with such fondness, and that I could not begin to imagine his loss.

Towards the end of my first year after qualification, I found myself reflecting on the many deaths I had attended in that year: the youngest, a sixteen-year-old lad with an aggressive and rare bone-marrow cancer; the saddest, a young mum whose infertility treatments may have been responsible for her death from breast cancer just before her precious son’s fifth birthday; the most musical, an elderly lady who asked the ward sister and me to sing ‘Abide With Me’ for her, and who breathed her last just before we ran out of verses; the longest-distance, the homeless man who was reunited with his family and transported the length of England over two days in an ambulance, to die in a hospice near his parents’ home; and the one that got away – my first cardiac arrest call, a middle-aged man who was post-op and stopped breathing, but who responded to our ministrations and walked out of the hospital a well man a week later.

This is when I noticed the pattern of dealing with dying. I am fascinated by the conundrum of death: by the ineffable change from alive to no-longer-alive; by the dignity with which the seriously ill can approach their deaths; by the challenge to be honest yet kind in discussing illness and the possibility of never getting better; by the moments of common humanity at the bedsides of the dying, when I realise that it is a rare privilege to be present and to serve those who are approaching their unmaking. I was discovering that I was not afraid of death; rather, I was in awe of it, and of its impact on our lives. What would happen if we ever ‘found a cure’ for death? Immortality seems in many ways an uninviting option. It is the fact that every day counts us down that makes each one such a gift. There are only two days with fewer than twenty-four hours in each lifetime, sitting like bookends astride our lives: one is celebrated every year, yet it is the other that makes us see living as precious.

French Resistance

Sometimes, things that are right in front of our noses are not truly noticed until someone else calls them to our attention.

Sometimes, courage is about more than choosing a brave course of action. Rather than performing brave deeds, courage may involve living bravely, even as life ebbs. Or it may involve embarking on a conversation that feels very uncomfortable, and yet enables someone to feel accompanied in their darkness, like ‘a good deed in a naughty world’.

Here’s Sabine. She is nearly eighty. She has a distinguished billow of silver-white hair swept into a knotted silk scarf, and she wears a kaftan (the genuine article, from her travels in the Far East in the 1950s) instead of a dressing gown. She is in constant motion in her hospice bed, playing Patience, applying her maquillage, moisturising her sparrowesque hands. She drinks her tea black and derides the ‘You call that coffee?’ offered by the beverages trolley. She has a French accent so dense it drapes her speech like an acoustic fog. She is the most mysterious, self-contained creature we have encountered in our newly built hospice.

Sabine has lived in England since 1946, when she married a young British officer her Resistance cell had hidden from Nazi troops for eighteen months. Peter, her British hero, had parachuted into France to support the Resistance. He was a communications specialist, and had helped them to build a radio from, by the sound of it, only eggboxes and a ball of string. I suppose he may also have brought some radio components in his rucksack, but I dare not ask. Forty years later, her accent sounds as though she has just stepped off the boat at Dover, a new bride with high hopes. ‘Peter was so clever,’ she murmurs. ‘He could do any-sing.’

Peter was very brave. This is not in doubt: Sabine has his photograph and his medals on her bedside table. He died many years ago, after an illness that he bore with characteristic courage. ‘He was never afraid,’ she recalls. ‘He told me always to remember him. And I do, naturellement, I talk to him every day’ – and she indicates the photograph of her handsome husband, resplendent in dress uniform and frozen in monochrome at around forty years of age. ‘Our only sadness was that the Lord did not send us children,’ she reflects. ‘But instead we use our time for great travel and adventures. We were very ’appy.’

Her own medal for courage is pinned to her chest on a black and red ribbon. She tells the nurses that she has only taken to wearing it since she realised that she was dying. ‘It is to remind me that I too can be brave.’

I am a young trainee in the new specialty of palliative medicine. My trainer is the consultant in charge of our new hospice, and Sabine loves to talk to him. From his discussions with her, it emerges that he is bilingual because his father was a Frenchman, and also a Resistance fighter. He occasionally has conversations with Sabine in French. When this happens, she sparkles and moves her hands with animation; the symmetrical Gallic shrugs between them amuse us greatly. Sabine is flirting.

And yet, Sabine is keeping a secret. She, who wears her Resistance Medal and who withstood the terror of the war, is afraid. She knows that widespread bowel cancer has reached her liver and is killing her. She maintains her self-possession when she allows the nurses to manage her colostomy bag. She is graceful when they wheel her to the bathroom and assist her to shower or bathe. But she is afraid that, one day, she may discover that she has pain beyond her ability to endure, and that her courage will fail her. If that should happen, she believes (with a faith based on 1930s French Catholicism mixed with superstition and dread) she will lose her dignity: she will die in agony. Worse: her loss of courage at the end will prevent her forever from rejoining her beloved husband in the heaven she so devoutly believes in. ‘I will not be worthy,’ she sighs. ‘I do not have the courage that I may require.’

Sabine confesses this deep-seated fear while a nurse is drying those silver tresses after a shower. The nurse and Sabine are looking at each other indirectly, via the mirror. In some way, that dissociation of eye contact, that joint labour at the task in hand, enabled this intimate conversation. The nurse was wise; she knew that reassurance would not help Sabine, and that listening, encouraging, allowing the full depth of her despair and fear to be expressed, was a vital gift at that moment. Once her hair was dressed, her silk scarf in place and Sabine indicated that the audience was over, the nurse asked permission to discuss those important concerns with our leader. Sabine, of course, agreed: in her eyes our leader was almost French. He would understand.

What happened next has lived with me, as if on a cinema reel, for the rest of my career. It formed my future practice; it is writing this book. It has enabled me to watch dying in a way that is informed and prepared; to be calm amidst other people’s storms of fear; and to be confident that the more we understand about the way dying proceeds, the better we will manage it. I didn’t see it coming, but it changed my life.

Our leader requested that the nurse to whom Sabine had confided her fear should accompany him, and added that I might find the conversation interesting. I wondered what he was going to say. I anticipated that he would explain about pain management options, to help Sabine be less worried about her pain getting out of control. I wondered why he wanted me to come along, as I felt I was already quite adept at pain management conversations. Ah, the confidence of the inexperienced …

Sabine was delighted to see him. He greeted her in French, and asked her permission to sit down. She sparkled and patted the bed, indicating where he should sit. The nurse sat in the bedside chair; I grabbed a low stool and squatted down on it, in a position from which I could see Sabine’s face. There were French pleasantries, and then our leader came to the point. ‘Your nurse told me that you have some worries. I am so glad you told her. Would you like to discuss this with me?’

Sabine agreed. Our leader asked whether she would prefer the conversation to be in English or French. ‘En Anglais. Pour les autres,’ she replied, indicating us lesser beings with benevolence. And so he began.

‘You have been worrying about what dying will be like, and whether it will be painful for you?’

‘Yes,’ she replied. I was startled by his direct approach, but Sabine appeared unsurprised.

‘And you have been worrying that your courage may fail?’

Sabine reached for his hand and grasped it. She swallowed, and croaked, ‘Oui.’

‘I wonder whether it would help you if I describe what dying will be like,’ he said, looking straight into her eyes. ‘And I wonder whether you have ever seen anyone die from the illness that you have?’

If he describes what? I heard myself shriek in my head.

Sabine, focused and thoughtful, reminisced that during the war a young woman had died of gunshot wounds in her family’s farmhouse. They had given her drugs that relieved her pain. Soon after, she stopped breathing. Years later, Sabine’s beloved husband had died after a heart attack. He collapsed at home and survived to reach hospital. He died the following day, fully aware that death was approaching.

‘The priest came. Peter said all the prayers with him. He never looked afraid. He told me goodbye was the wrong word, that this was au revoir. Until we see each other again …’ Her eyes were brimming, and she blinked her tears onto her cheeks, ignoring them as they ran into her wrinkles.

‘So let’s talk about your illness,’ said our leader. ‘First of all, let’s talk about pain. Has this been a very painful illness so far?’

She shakes her head. He takes up her medication chart, and points out to her that she is taking no regular painkillers, only occasional doses of a drug for colicky pain in her abdomen.

‘If it hasn’t been painful so far, I don’t expect it to suddenly change character and become painful in the future. But if it does, you can be sure we will help you to keep any pain bearable. Can you trust us to do that?’

‘Yes. I trust you.’

He continues, ‘It’s a funny thing that, in many different illnesses that cause people to become weaker, their experience towards the end of life is very similar. I have seen this many times. Shall I tell you what we see? If you want me to stop at any point, you just tell me and I will stop.’

She nods, holding his gaze.

‘Well, the first thing we notice is that people are more tired. Their illness saps their energy. I think you are already noticing that?’

Another nod. She takes his hand again.

‘As time goes by, people become more tired, more weary. They need to sleep more, to boost their energy levels. Have you noticed that if you have a sleep during the day, you feel less weary for a while when you wake up?’

Her posture is changing. She is sitting up straighter. Her eyes are locked on his face. She nods.

‘Well, that tells us that you are following the usual pattern. What we expect to happen from now on is that you will just be progressively more tired, and you will need longer sleeps, and spend less time awake.’

Job done, I think. She can expect to be sleepy. Let’s go … But our leader continues talking.

‘As time goes by,’ he says, ‘we find that people begin to spend more time sleeping, and some of that time they are even more deeply asleep, they slip into a coma. I mean that they are unconscious. Do you understand? Shall I say it in French?’

‘Non, I understand. Unconscious, coma, oui.’ She shakes his hand in hers to affirm her understanding.

‘So if people are too deeply unconscious to take their medications for part of the day, we will find a different way to give those drugs, to make sure they remain in comfort. Consoler toujours. Yes?’

He must be about to stop now, I think. I am surprised that he has told her so much. But he continues, his gaze locked onto hers.

‘We see people spending more time asleep, and less time awake. Sometimes when they appear to be only asleep, they are actually unconscious, yet when they wake up they tell us they had a good sleep. It seems we don’t notice that we become unconscious. And so, at the very end of life, a person is simply unconscious all of the time. And then their breathing starts to change. Sometimes deep and slow, sometimes shallow and faster, and then, very gently, the breathing slows down, and very gently stops. No sudden rush of pain at the end. No feeling of fading away. No panic. Just very, very peaceful …’

She is leaning towards him. She picks up his hand and draws it to her lips, and very gently kisses it with great reverence.

‘The important thing to notice is that it’s not the same as falling asleep,’ he says. ‘In fact, if you are well enough to feel you need a nap, then you are well enough to wake up again afterwards. Becoming unconscious doesn’t feel like falling asleep. You won’t even notice it happening.’

He stops and looks at her. She looks at him. I stare at both of them. I think my mouth might be open, and I may even be leaking from my eyes. There is a long silence. Her shoulders relax and she settles against her pillows. She closes her eyes and gives a deep, long sigh, then raises his hand, held in both of hers, shakes it like shaking dice, and gazes at him as she says, simply, ‘Thank you.’ She closes her eyes. We are, it seems, dismissed.

The nurse, our leader and I walk to the office. Our leader says to me, ‘That is probably the most helpful gift we can ever give to our patients. Few have seen a death. Most imagine dying to be agonising and undignified. We can help them to know that we do not see that, and that they need not fear that their families will see something terrible. I never get used to having that conversation, even though it always ends by a patient knowing more yet being less afraid.’

Then, kindly overlooking my crumpled tissue, he suggests, ‘Shall we have a cup of tea?’

I escape to brew the tea and wipe my tears. I begin to reflect on what I have just seen and heard. I know that he has just described, with enormous skill, exactly what we see as people die, yet I had never considered the pattern before. I am amazed that it is possible to share this amount of information with a patient. I review all my ill-conceived beliefs about what people can bear: beliefs that had just scrolled through my startled and increasingly incredulous consciousness throughout that conversation; beliefs that would have prevented me from having the courage to tell Sabine the whole truth. I feel suddenly excited. Is it really within my gift to offer that peace of mind to people at the ends of their lives?

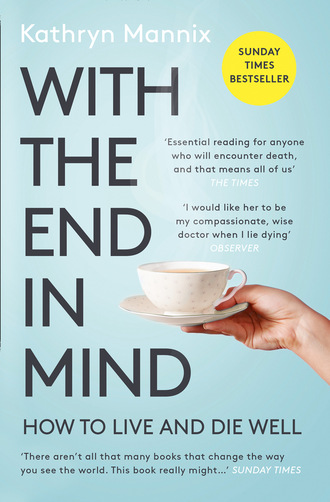

This book is about my learning to observe the details of that very pattern our leader explained to Sabine all those years ago. In the next thirty years of clinical practice, I found it to be true and accurate. I have used it, now adapted to my own words and phrases, to comfort many hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of patients in the same way that it brought such comfort to Sabine. And now I am writing it down, telling the stories that illustrate that journey of shrinking horizons and final moments, in the hope that the knowledge that was common to all when death took place at home can again be a guide and comfort to people contemplating death. Because in the end, this story is about all of us.

Tiny Dancer

The pattern of decline towards death varies in its trajectory, yet for an individual it follows a relatively even flow, and energy declines initially only year to year, later month to month, and eventually week by week. Towards the very end of life energy levels are less day by day, and this is usually a signal that time is very short. Time to gather. Time to say any important things not yet said.

But sometimes there is an unexpected last rise before the final fall, a kind of swansong. Often this is unexplained, but occasionally there is a clear cause, and sometimes the energy rush is a mixed blessing.

Holly has been dead for thirty years. Yet this morning she is steadily dragging herself out of the recesses of my memory and onto my page. She woke me early; or perhaps it was waking on this misty autumn morning that brought her last day to mind. She twisted and twirled her way into the focus of my consciousness: initially just images like an old silent-movie reel showing disjointed snatches of her pale smile, her pinched nose, her fluttering hand movements. And then her laugh arrived, with the crows outside my window: her barking, rasping laugh, honed by the bitter winds along the industry-riven river, by teenage smoking and premature lung disease. Finally, she drew me from my warm bed and sat me down to tell her story, while mist was still bathing the gardens beneath an autumn dawn.

Thirty years ago, arriving at my first hospice job with several years’ experience of a variety of medical specialties, some training in cancer medicine and a freshly minted postgraduate qualification, I probably saw myself as quite a catch. I know that I was buoyed up by the discovery that palliative care fitted all my hopes for a medical career: a mixture of teamwork with clinical detective work to find the origins of patients’ symptoms in order to offer the best possible palliation; of attention to the psychological needs and resilience of patients and their families; honesty and truth in the face of advancing disease; and recognition that each patient is a unique, whole person who is the key member of the team looking after them. Working with, rather than doing to: a complete paradigm shift. I had found my tribe.

The leader of this new hospice had been on call for the service without a break until my arrival in early August. Despite this he exuded enthusiasm and warmth, and was gently patient with my questions, my lack of palliative care experience, my youthful self-assurance. It was a wonder to see patients I already knew from the cancer centre, looking so much better than when they had recently been in my care there, now with pain well controlled but brains in full working order. I may have thought highly of myself, but I recognised that these people were far better served by the hospice than they had been by the mainstream cancer services. Perhaps my previous experiences were only a foundation for new knowledge; perhaps I was here not to perform, but to learn. Humility comes slowly to the young.

After my first month of daily rounds to review patients, adjusting their medication to optimise symptom control but minimise side-effects, watching the leader discuss mood and anxieties as well as sleep and bowel habit, attending team meetings that reviewed each patient’s physical, emotional, social and spiritual wellbeing, the leader decided that I was ready to do my own first weekend on call. He would be back-up, and would come in to the hospice each morning to answer any queries and review any particularly tricky challenges, but I would take the calls from the hospice nurses, from GPs and hospital wards, and try to address the problems that arose. I was thrilled.

Holly’s GP rang early on the Saturday afternoon. Holly was known to the city’s community palliative care nurses, whose office was in the hospice, so he hoped that I might know about her. She was in her late thirties, the mother of two teenagers, and she had advanced cancer of the cervix, now filling her pelvis and pressing on her bladder, bowels and nerves. The specialist nurses had helped the GP to manage her pain, and Holly was now able to get out of bed and sit on the outdoor landing of her flat to smoke and chat with her neighbours. When she developed paralysing nausea in the previous week, her symptoms were improved greatly by using the right drug to calm the sickness caused as her kidneys failed, as the thin ureter tubes that convey the urine from kidneys to bladder were strangled by her mass of cancer.

Today she had a new problem: no one in her flat had slept all night, because Holly wanted to walk around and chat to everyone. Having hardly walked more than a few steps for weeks, overnight she had suddenly become animated and active, unable to settle to sleep, and she had woken her children and her own mother by playing loud music and attempting to dance to it. The neighbours had been banging on the walls. At first light her mother had called the GP. He found Holly slightly euphoric, flushed and tired, yet still dancing around the flat, hanging onto the furniture.

‘She doesn’t seem to be in pain,’ the GP explained to me, ‘and although she’s over-animated, all her thought content is normal. I don’t think this is psychiatric, but I have no idea what is going on. The family is exhausted. Do you have a bed?’

All our beds were full, but I was intrigued. The GP accepted my offer to visit Holly at home, so I retrieved her notes from the community team office and set off through the receding autumn mist to the area of the city where long terraces of houses run down to the coalyards, ironworks and shipbuilders that line the river’s banks. In places the terraces were interrupted by brutal low-rise blocks of dark brick flats crowned with barbed-wire coils and pierced by darkened doorways hung with cold neon lights in tamper-proof covers. These palaces bore unlikely names: Magnolia House, Bermuda Court, and my destination, Nightingale Gardens.

I parked my car at the kerbside and sat for a moment, surveying the area. Beside me rose the dark front of Nightingale Gardens. On the ground floor, a bare stone pavement ran from the kerb to the tenement block: not a tree or a blade of grass to garnish these ‘gardens’, which certainly never saw or heard a nightingale. Across the road, a terrace of council-owned houses grinned a toothy smile of white doors and window frames, all identical and recently painted. Some of the tiny front gardens displayed a few remnants of late-summer colour; rusting bed-frames or mangled bicycles adorned others. Several children were playing in the street, a game of catch with a tennis ball played while dodging a group of older boys who were aiming their bikes at the players. Yelps of excitement from the kids, and from a group of enthusiastic dogs in assorted sizes who were trying to join in.

I collected my bag and approached Nightingale Gardens. I needed to find number 55. An archway marked ‘Odds’ led to a dank, chilly concrete tunnel. My breath was visible in the gloomily lit staircase. On the landing, all the door numbers were in the thirties. Up another couple of flights I found the fifties, and halfway along the balcony corridor that overlooked the misty river, and was itself overlooked by cranes rising above the mist like origami giants, number 55. I knocked and waited. Through the window I could hear Marc Bolan telling me that I won’t fool the children of the revolution.

The door was opened by a large woman in her fifties wearing a miner’s donkey jacket. Behind her was a staircase leading to another floor, and beside her the living-room door swung open to reveal a diminutive, pale woman leaning on a table and moving her feet to the T. Rex beat.

‘Shut the door, will you?’ she trilled across to us. ‘It’s cold out there!’

‘Are you the Macmillan nurse?’ the older woman asked me. I explained that I worked with the Macmillan nurses, but that I was the doctor on call. She beckoned me inside with an arc of her chin, while simultaneously indicating with animated eyebrows that the younger woman was causing her some concern. Then she straightened up, shouted, ‘I’m off to get more ciggies, Holly!’ and left the flat.