Полная версия

Enjoy, Comprehend, Love. Entering the Spaces of Conscious Love

A talented verse carries and conveys to us surprisingly filled meanings that are perceived beyond both imagination and rational thinking. It can be said that our mind, on the wings of poetry, rises to the heights or sinks to the depths of the understanding of love.

The very poetic inspiration coincides in many ways with the thrill of love and the rise of a loving soul. The interpenetration of these experiences is expressed in the chased lines of another poem by Nabokov:

Inspiration is the voluptuousness

of the human self:

a hotly growing happiness, —

a moment of nothingness.

The voluptuousness is the inspiration…

of a body as sensitive as the spirit:

you have seen, you have flashed for a moment, —

and in a tremor you are extinguished.

But when the thunderous pleasure

was gone, and you fell silent,

in the secret place of life arose:

a heart or a verse…

Love Prose or Love Stories

As for love prose, it has the difficult task of choosing between dry or moist words about love, as the psychologist Eric Berne elegantly observed. In terms of reflections on love, many works of fiction and popular science literature belong to the genre of love stories. In our youth, we are fascinated by the dramatic fate of the characters, we empathize with their anxious feelings, and sometimes we put off in our minds the images that have excited us. At a mature age, we are able to follow the vicissitudes of love’s fates with sympathetic understanding, but with unwavering fascination. Talented love stories can provide rich food for thought, but tend to leave us with only a vague, vanishing trace.

In prose, our brain reacts to the plot, the sequences of events, the fates of the characters, and their connections. Perhaps neurobiologists are right to point out that similar structures – sequences of electrical signals and intricate connections of neurons – operate in our minds.

We will make extensive use of outstanding love stories in the subsequent work as the most vivid mental images to illustrate thinking about love.

Philosophy

In the language of philosophy, we turn to the initial, basic concepts of love, generalizing its main properties and deep sources. So, the ancient Greeks, when speaking of love, used the following concepts: Agape – sacrificial unconditional love, Eros – passionate love, Ludus – love-game, Mania – love as an obsession, Philia – love-friendship, Pragma – rational love as mutual services, Storge – love as family affection, Xenia – love as generosity and hospitality.

In the philosophy of love, one can often find the justification of love as an in-depth consideration of one or more of its above-mentioned sides. For example, in 1973, Canadian sociologist John Alan Lee, in his book , proposed considering three basic (Eros, Storge, Ludus), three combined styles of love (Mania (EL), Pragma (SL), Agape (ES)) and nine tertiary, and this classification was confirmed by sociological surveys. Colours of Love

There are other philosophical theories of love that connect it with a single, as a rule, metaphysical source. For example, the supreme good, the cosmic generative force or God. Here, the intellectual efforts of the authors of such theories go beyond conceivable limits to the level associated with prophecy or other superhuman breakthrough of consciousness. Therefore, in our journey through the spaces of conscious love, only when absolutely necessary will we delve into the wilds of this fog-covered realm.

Fortunately, ancient people created quite fascinating ways of describing it allegorically, in modern terms, a virtual visit to metaphysical origins. In this vein, we will touch on the topic of the metaphysics of love.

Metaphysics of love

In this area of our thinking, we seek to discover what precedes the earthly manifestation of love, which is its transcendent beginning, cause and ultimate goal. This is done by resorting to special intellectual constructions, such as myths.

In ancient times, love was represented in the form of mythological creatures: Aphrodite (Venus) – the goddess of love, born either from sea foam, or in a shell and set foot on the ground on the island of Cyprus. Her husband is the lame Hermes (their descendant is Hermaphrodite). From her lover, the god of war Ares, the god of love, Eros (Cupid), was born. Aphrodite was in love with the earthly handsome Adonis, who was killed by Ares incarnated into a boar.

From the union of Ares and Aphrodite, Himeros (god of sexual desire), Eros (love), Anteros (hatred from love), Pophos (god of love longing), Phobos (fear), Deimos (horror) and Harmonia (goddess of consent) were born.

Plato also cites another myth about the birth of Eros from Poros, the god of abundance and wealth (his mother Metida – the goddess of wisdom and cunning) and the nymph Phenia – the deity of nature, a symbol of need and poverty.

For example, in the myth of , the soul is represented by the image of Psyche. Accordingly, this myth is an allegory about the path of the human soul in love. You can familiarize yourself with it. Eros and Psyche

We will draw your attention to the fact that Psyche’s curiosity twice leads her to almost disastrous consequences. Wanting to see her mysterious lover, she burns Eros with oil from a lamp, and he flies to Olympus. Then, fulfilling the task of Aphrodite, she, having received in the kingdom of the dead from Persephone (goddess of fertility) a box with miraculous beauty tools, opens it and falls into eternal sleep.

These episodes can be viewed as a warning against the dangers that await those who seek to penetrate the innermost secrets of love, that is, you and me, dear readers. However, the risks are not fatal – Zeus grants Psyche immortality. Let us take note of this and continue our preparations for the journey through the spaces of love.

Psychology

The language of science is a tribute to the special turn of the modern mind, which cannot do without scientific confirmation of certain considerations through laboratory experiments or in situ observations. The areas of psychological research on love are vast and varied, from observing facial expressions, measuring the physiological reactions of lovers, and large-scale surveys of men and women about their intimate lives, to analyzing love hormones and scanning the brains of test subjects in different states of love relationships. At the same time, one can hardly point to any new discoveries made in psychology, ethology, social psychology and other scientific disciplines that have turned to the study of love, because love is as old as the world and a lot has already been said.

The achievements of the sciences so far boil down mainly to giving us the opportunity to talk about love in a more modern and sterile language in the hope of understanding and more clearly formulating the innermost mysteries of love known for a long time to a select few.

At the same time, it should be borne in mind that in modern psychology one can find a fairly large variety of approaches to determining the origins of our tender attachments and, accordingly, theories of love.

Here are some definitions of love in psychology:

Love is the highest emotion.

Love is a strong desire for a relationship with a single, specific partner.

Love is an intense feeling associated with sexual arousal, the desire to be one’s own personally significant traits with the maximum fullness represented in the life of another.

Psychologists have tried, but so far cannot satisfactorily resolve the following hard questions of love:

1. Love undergoes a transformation of its states throughout the life cycle. For example, falling in love and mature love.

2. Love is distributed between two lovers and depends on the degree of reciprocity.

3. Love covers different levels and structures of the human psyche.

4. Manifestations of love coincide with the symptoms of mental disorders.

Perhaps we use the same word to describe completely different mental states? In this regard, the Canadian writer Margaret Atwood wittily observed that “the Eskimos have 52 words for snow, because this is important to them. There should be at least as many words for love.”

In what follows, we will dive into sterilized by the logic waters of 5—6 basic concepts of love from the baggage of psychological science.

Summing up our acquaintance with the languages of love, we can conclude that, going on a journey through the spaces of love, one should be prepared to talk about it in different languages. The task is not easy if you do not notice their interrelation. The scientific concepts of the psychology of love stem from philosophical ideas and are rooted in metaphysical insights. Literary images deepen and embellish the psychology of love with the language of everyday or refined prose, as well as with chased formulas of poetic inspiration. Poetry, in turn, often elevates to philosophical generalizations.

Let us now get acquainted with two well-known researchers of the driving forces of love attraction – the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and the psychologist Sigmund Freud, whose delusions are also valuable for comprehending the mysteries of love.

(sounds in the popular song “Oh, the viburnum is blooming”)(reported in the song from the movie “Three Days in Moscow”)(translated by Mila Gee)Following the Love Theories Leading Down

Arthur Schopenhauer, at the time of writing his famous essay “The Metaphysics of Sexual Love” in 1844, considered love as “philosophically undeveloped material.” He was not satisfied with the reflections on the love of his predecessors: Plato (myths and legends), Rousseau (wrong), Kant (superficial), Spinoza (naive). He proposed his own original solution to the riddle of love, which consists in the fact that, on the one hand, it is nothing more than “some kind of ghost woven out of thin air,” and, on the other hand, “the most powerful and active of all the springs of being.” Schopenhauer gives a wide range of examples of the power of love. For example, it is “the ultimate goal of almost every human aspiration,” has “a harmful effect on the most important matters and events,” gets “with its notes and curls even into ministerial briefcases and philosophical manuscripts,” takes away “the conscience of the honest and makes a traitor of the faithful.”

The solution to the riddle of love, according to Schopenhauer, is that it has its own special ultimate goal, which is “more important than other goals of human life.” This goal is hidden from lovers by nature and replaced by more reliable stimuli associated with selfish goals of pleasure. It aims to “create the next generation.” In his aphoristic manner, Schopenhauer conveys the main idea of his own theory of love: “the pleasure that the other sex gives us, no matter how objectively it may seem, is in fact nothing more than a disguised instinct, that is, the spirit of a kin, striving to preserve its type.”

According to this theory, when passionate gazes of lovers meet, they are guided by the emerging new life. It is true that Schopenhauer has to admit that the sparks of love “like all embryos are for the most part crushed.” The desire for beautiful women, which, along with the sexual instinct, guides the choice of an object, is also inherent in us by nature, as the attraction of the spirit of the kin to the “norm of human appearance.” The spirit of the kin through the sense of beauty and sexual instinct ignites our reckless passionate love. However, the choice of a marriage partner is made taking into account a number of individual reasonable considerations, such as obtaining qualities that oneself lacks in order to “correct the generic defect.”

In accordance with his theory, Schopenhauer explains some of the paradoxical manifestations of love. He sees a contradiction in poets who dream of endless bliss with a certain woman, but yearn and grieve that ideal love is unattainable. The explanation is that these dreams are not the direct needs of the individual, but the “sighs of the race”, which alone can have infinite desires.

Schopenhauer’s theory of love cannot be denied coherent logic, and most importantly, the exposure of key issues involved in love relationships. We must fully agree that love has its own ultimate goal, which is hidden in a host of turbulent feelings and is not fixed by our consciousness. But the sexual instinct and procreation as the essence of love, with all their significance, still miss something important and are too far from the main thing that everyone directly experiences in love. There is an internal dissonance and a desire to continue the search for another not so mundane center of gravity of love.

It is tempting to exclaim after Vladimir Nabokov: “Oh, love. I’m going back down the ladder of years for your mystery”, and try to get to where “I was only a small comma on the first page of creation.” At the same time, one would hope that this jump back will only be a swing for a throw forward.

Moving down the ladder of years on the love map is indicated by a series of warning signs about slippery roads and dead ends. One of them is located just behind the sign: “Entrance to the territory of the libido of the Great and Terrible Sigmund Freud.” Having wandered here among the embryos of sexual activity in early childhood, the crazy fixations of the libido on various, sometimes bizarre objects, one can leave with the disappointing impression that “love is fundamentally as animalistic now as it has been for centuries. Love inclinations are difficult to cultivate, their cultivation sometimes gives too much, sometimes too little.”

One of the critics of Freud’s theory, the social psychologist Erich Fromm, believed that Freud considered only irrational love associated with the transfer of children’s objects of love, and as a phenomenon of mature consciousness, love for him did not exist.

Despite the fact that in modern psychology Freud’s theory of love occupies an honorable, but rather limited place among other worthy concepts, here and there one can meet straightforward followers of Freudianism. For example, media psychologist Mikhail Labkovsky believes that “love is your childhood experiences about relationships with parents,” and explains all problems in relationships on the basis of neurotic failures of children’s love for their parents.

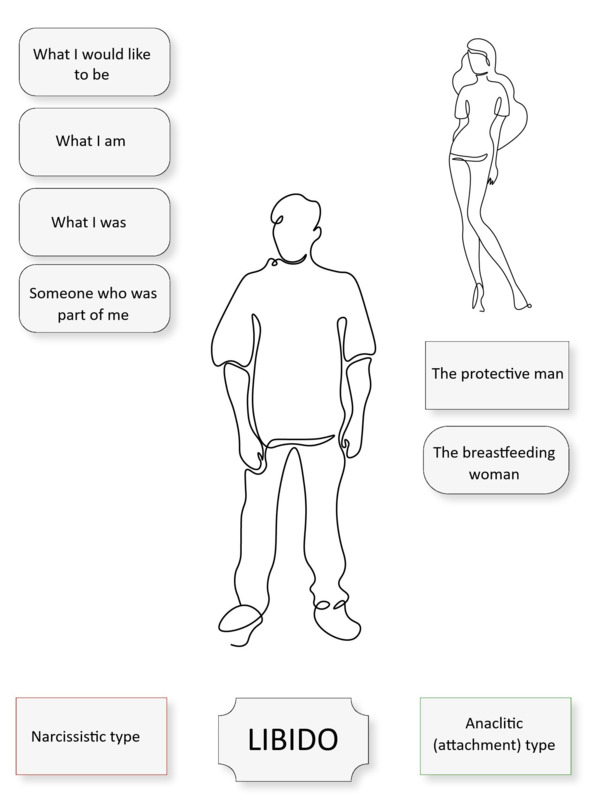

However, not everything is so hopelessly determined. In the Freudian construction of the psyche, self-libido and object-libido are distinguished. The self-libido stems from childhood delusions of omnipotence and narcissism and develops under the influence of significant others into the sef-ideal. According to Freud, “falling in love consists in the outpouring of the self-libido on the object,” and “the sexual ideal can enter into an interesting relationship of mutual assistance with the self-ideal.” The object of love can even act as a “substitute for the never achieved self-ideal.” Now this is more interesting. So let’s leave the zone of Freudianism, considering how in our subconscious mind the ideal sexual object interacts with the self-ideal, while we are in love with a specific person in the flesh.

It is no secret that the theories of Schopenhauer and Freud, as well as other conceptualizations of love, are a reflection of the individual worldviews and psychological peculiarities of their authors. Recklessly following their logic, we involuntarily fall into the trap of a perception of love predetermined by these features and already chewed. Moreover, the trap that our thinking falls into becomes voluntary for a number of reasons. Having spent a lot of time and effort trying to understand the premises of a popular theory, its new concepts, the logic of reasoning, conclusions or inconsistencies, we involuntarily begin to appreciate what we have acquired for lack of a better one.

It seems that the search for the laws of love exclusively in the wake of concepts that appeal to reason leads either to the camp of sectarians – the witnesses of Freud, Schopenhauer, Spinoza, Feuerbach, Frome and other gurus of love, or to the detachment of eternally wandering from one ready-made theory of love to another.

We will describe the strategy of our path, which consists in combining the phenomenological and structural approaches with the involvement, if necessary, of other tools of thinking, but for now we will complete a short review of theories of love, pointing out the main, in our opinion, sources of the theory of conscious love.

The types and paths of love according to Sigmund Freud

Sources of the Theory of Conscious Love

At the beginning of the 19th century, taking on a boldness bordering on impudence, the French writer Stendhal published his experiments . He foresaw the hard fate of this “ill-fated book” and ten years after its publication “found only seventeen readers.” A hundred years later, the laws of love outlined in the were chosen as the starting point, the “erroneous” conclusions of which needed to be identified and corrected, to create the insightful by the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset. By this time, the “ill-fated book” had become “one of the most widely read books.” The author of notes that it is not only “read with rapture”, but is also an element of the boudoir entourage of “the marquise, actress and society lady”, indicating that “they should understand love.” On Love Experiments Etudes on Love Etudes

These dives into the nature of love, separated by a century, form two poles of intense intellectual efforts of the new time, two bright searchlights that penetrate new shells of illusions and delusions and shed light on the primordial territory of the space of love. It is possible, using a well-known aphorism, to say with confidence that all subsequent theories of love are notes in the margins of and . Experiments Etudes

Stendhal is an example of an interested observer who, in a string of love affairs and turmoil of infatuations, both his own and those of the high society he observes, suddenly discovers amazing regularity and inevitable patterns of love. Ortega y Gasset, in his study of the paradoxes and mysteries of love in contemporary society, relies on the seemingly long-gone ideas of Plato’s love and rediscovers the deep, unshakable true essence of love.

As for Plato’s own dives into the nature of love, which are an invaluable treasure trove of revelations, it should be noted that access to them requires preparation and the use of special methods of thinking. Plato’s love dialogues and , which seem to reveal the mysteries of love, have often been the source of new myths and misconceptions. For example, the myth of exemplary “Platonic love” as a purely spiritual love in isolation from bodily attraction is widely circulated. Another example: the famous Ukrainian philosopher Andriy Baumeister believes that in the dialogue Plato hides behind the mask of Aristophanes and, accordingly, his speech about the separation of androgynes and their desire to merge with their half reveals the essence of love. Lysis, Phaedrus Symposium Symposium

The works of these three authors (Plato, Stendhal, Ortega y Gasset) have become for us the cornerstones of the pyramid of knowledge about the nature of conscious love, and we will further examine their ideas in detail.

For now, as an aside, let’s join join the participants in the table conversation about love, which has become a philosophical tradition, and reflect on a passage from the works of Plato. In the dialogue , where the lovers of wise speeches decide to talk about the god of love Eros, Agathon (his speech is the fifth) lists what properties Eros has: Symposium

Beauty and perfection: young – avoids old age; gentle – dwells only in soft souls and leaves if it meets a harsh temper; flexible forms – enters the soul imperceptibly; handsome – lives among flowers, where everything blooms and smells sweet, does not stay with the pale and faded.

Virtues:: he does not recognize any violence – only voluntary and mutual consent; prudence – the ability to curb desires and passions, and since passions are weaker than Eros, it means that he is unusually reasonable; courage – even takes possession of Ares, the god of war, the lover of Aphrodite, i.e. ready to compete with him.

Wisdom: source of poetry, gives rise to all living things, skill in arts (muses) and crafts (dealing with love).

The ordering of all the affairs of the gods: earlier, the reason for what was created by the gods was Necessity (terrible deeds), with the advent of Eros, deeds began to be done out of love for the beautiful.

And at the end of the speech, he cannot refrain from the sublime poetic syllable:

Tolerant to the good, honored by the wise, beloved by the gods; the sigh of the unlucky, the wealth of the fortunate; the father of luxury, grace and bliss, joys, passions and desires; guarding the noble, and despising the worthless, he is the best mentor, helper, savior and companion in fears, and in torment, and in thoughts, and in languor.

But this seemingly beautiful and exhaustive speech that characterizes Eros is far from the truth, which Socrates reveals, figuring out, for example, that if in love they strive for something, they want to get what they themselves do not possess, what they need, and, consequently, Eros cannot be perfectly beautiful and immensely good, since he strives for beauty and goodness. So the true properties of Eros and the mysteries of love will already be revealed by Socrates in the next speech of the dialogue . Symposium

I hope this example gives you an idea that it is not uncommon to find fascinating, enthusiastic claims of truth about love that are actually superficial and do not reveal the true driving forces of love.

And now let’s try to delve a little into the nature of the influence of love on our life path in big and small ways and consider how self-knowledge and conscious love correlate.

Self-Knowledge and Conscious Love

Here we would like to show the close connection of conscious love with one of the main tasks set (by the ancient gods) for man, expressed in the maxim: “Know thyself.”

An example of exceptional devotion to self-knowledge and life, inextricably linked with its study, is the ancient philosopher Socrates. Legend has it that the Pythia of the Delphic Temple foretold him that he was the wisest of men. Since he was extremely surprised by such a flattering prophecy, this prompted Socrates to look for people who would be wiser than him. Unlike other “wise men”, who were unconditionally confident in their knowledge, Socrates doubted both the solutions offered by others and his own knowledge. He was ready to critically analyze any questions in order to find more substantiated answers closer to the truth in joint reasoning. As a result of such conversations, he came to the conclusion that his small advantage in wisdom lies precisely in his openness to new knowledge. Socrates considered life without its exploration meaningless.

In Plato’s dialogue , Socrates, as if contradicting himself, declares himself an expert in love affairs: “I affirm that I do not understand anything but love.” But then the contradiction in his statements can be avoided only by concluding that love is the very path he has chosen to study life – a constant search for and approximation to the truth. Symposium

As for the personal life of Socrates, he married somewhere at the age of 50 to twenty-year-old Xanthippe and had three children. There are a number of stories about their uneasy relationship. In particular, Socrates, recommending a man to marry, argued this as follows: “If you are lucky and your wife is good, you will become happy, if you are not lucky, you will be a philosopher.” There are also references to his second wife, Mirto. We will talk more about his relationship with his disciple and handsome Alcibiades in the chapter Platonic Love.