Полная версия

Whites

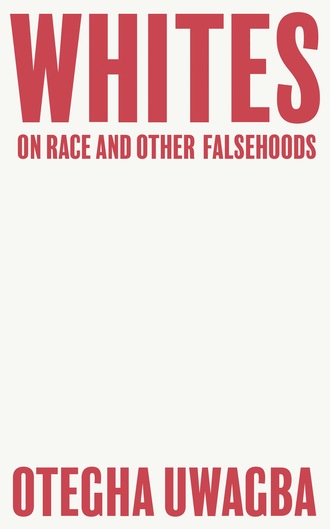

WHITES

ON RACE AND OTHER FALSEHOODS

Otegha Uwagba

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020

Copyright © Otegha Uwagba 2020

Cover design: Ellie Game

Otegha Uwagba asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008440428

Ebook Edition © November 2020 ISBN: 9780008440435

Version: 2020-10-05

Dedication

‘To know our whites is to understand the psychology of white people and the elasticity of whiteness. It is to be intimate with some white persons but to critically withhold faith in white people categorically.’

Dr Tressie McMillan Cottom, Thick

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preamble

I still haven’t …

Perhaps the most …

A new phenomenon …

Social media is …

I spend the …

A problem: some …

After George Floyd …

A memory …

The question that …

In 1993 the …

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Otegha Uwagba

About the Publisher

PREAMBLE

This essay was written in the throes of an unthinkable summer, one where it seemed as though the entire world was teetering on the brink of collapse, and where I often imagined I could physically feel the shift from one era to another happening beneath my feet, could actually point at the fault line separating one period of time from the next and say, ‘There. That’s where it happened.’

And then, in the middle of that already strange season, George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black American man from Fayetteville, North Carolina, was killed by a white police officer – a death that Floyd’s brother would later describe as a ‘modern-day lynching’ – and the world burst into flames.

The days and weeks that followed brought to a head countless tensions and unspoken grievances, at both the civic and personal levels, and it was the ripple effect of those events that prompted me to finally begin writing this essay. The thoughts that follow are largely constructed from notes I started making around five years ago: a collection of miscellaneous observations and emotions piling up day by day, lost memories abruptly making themselves known again and taking on new significance when arranged on a shelf alongside twenty others.

Sifting through them, a very clear unifying theme quickly became obvious: not just ‘racism’ in a general sense – which is what I had thought I was writing about – but white people, and what is required to coexist with them if you yourself are not white. The colossal burden of that requirement.

Already, my first hurdle: I didn’t particularly want to write an essay about being Black that placed white people at its centre. I felt – still feel – deeply confronted by that prospect, wary of falling into the easy trap of evaluating Black experiences solely in relation to whiteness. As I weighed this up, an interview with the New York-based artist Rashid Johnson caught my eye. Part of a larger feature focusing on contemporary Black artists actively resisting the expectation to create work catering to the white gaze (as is often the unspoken mandate in creative fields),[1] Johnson noted that society consistently finds new ways ‘to position the work of Black artists as inherently being in response to the obstacles presented by a white world.’ That was the very opposite of what I wanted to do – produce something angled toward the white gaze, or write an essay that might become an emblem for progressive white people wanting to prove their credentials, wallowing in their guilt about the existence of a system that works to their advantage while doing nothing to divest from it.

All this to say that although I didn’t want to write an essay where white people took centre stage, as you’ll discover, that’s exactly what I’ve done. This essay is very much ‘a response to the obstacles presented by a white world’. It became clear to me that to write about navigating racism and not place white people at the centre of that narrative would be to elide the very thing I was trying to write about, because navigating racism is really a matter of navigating white people.

Perhaps that conclusion seems obvious, but it took me a little while to get there, and to work through my competing desires about how to approach this essay. On reflection, that push and pull – between what I wanted to do, and what racism necessarily requires of me – seems strangely apt, a facsimile of whiteness itself and the way it compels, overrides, distorts, and ultimately controls.

I still haven’t watched George Floyd die.

I’ve seen stills from that video embedded into news articles, and when I’m scrolling through social media I’ll occasionally stumble across a few seconds of his ordeal if a video clip unexpectedly begins to autoplay, but I haven’t watched the video that so many found themselves watching at the start of this summer. I haven’t watched a grown man undone by the knowledge of his impending death, pleading alternately for two life-giving forces, for his mother and for air. I haven’t witnessed the precise moment where he passes from living to dead, the last few dregs of life gurgling out of him, squeezed out beneath the heft of someone else’s knee.

Mostly this is because I already made that mistake a few months earlier, with Ahmaud Arbery. Shocked by what I’d read about his murder, but unable to wrap my head around the idea that such an egregiously violent act had somehow gone unpunished, I felt compelled to see it with my own eyes, even in my guilt at stripping this man of his last shred of dignity by gawping at the spectacle of his death. The video I found played itself on an endless loop, so I watched it again and again and again and again, committing every second to memory, trying to understand. His baggy white T-shirt, and loose running shorts. The off-screen tussle over a shotgun, and the sharp pop of gunfire before Arbery emerges back into frame, loping languidly across the street. At first it looks like he is breaking into a jog, about to resume his run, the situation resolved. But then a red stain blooms across his T-shirt and seconds later he collapses to the ground, limbs suddenly liquid. And then he’s dead.

I watched that sordid video enough times, can picture it so clearly in my mind’s eye even all these months later, that I knew I didn’t want to go through the same thing with George Floyd. I don’t want to accept that he’s dead, and that he died the way he did, so I keep skipping over that part of his story and the abject horror of those final eight minutes and forty-six seconds.

I’ve watched other videos of him though, videos from when he was still alive. It feels trite to say it but that’s how I feel he deserves to be remembered, how I want to remember him. A short snippet of him rapping (for a while Floyd was part of Houston’s chopped and screwed music scene, performing under the name Big Floyd). Another video in which he is offering motivational life advice, hinting at his own past struggles and urging resilience in the face of adversity, announcing in his gloopy southern drawl, ‘man, I love the world!’ The stories that have since emerged about his life from family and friends, and from his widowed fiancée, confirm that yes, George Floyd certainly did love the world, even if ultimately it didn’t love him back.

In the aftermath of his death came the truly unexpected: a prolonged and visceral, full-throated outpouring of rage, of global protests and riots and emotionally charged op-eds, demanding justice and prosecutions and change. The stuff that history books are made of, I thought, as I watched it all unfold, and in fact I have never before been so keenly aware that I am watching history being written. ‘Watching’ being the operative word here, because I was not ‘in it’ – not in the USA, the beating heart of the movement, nor out on the streets here in Britain, having decided that my responsibility not to risk passing the virus on to the loved ones I was isolating with outweighed my desire to protest. I experienced it all at a remove, filtered through the often opposing lenses of social and mass media – though even from that vantage point there was still plenty to see.

That George Floyd’s death would command so much attention is in some ways deeply surprising, given that it happened to coincide with our collectively being trapped in the horror of a global pandemic. Amid scenes that had the nightmarish, alt-reality quality of a Jordan Peele movie – masks, mass graves and growing piles of bodies, armed militias, sudden and incomprehensible, almost random death – one wonders how the unlawful killing of one Black man, when there have been so many, managed to cut through the noise, how George Floyd was not merely a tree falling unobserved in a forest.

But then as with Peele’s films, the nature and distribution of those deaths offered potent commentary on the ravages of structural racism, as evidence began to emerge that, certainly within Britain and the USA (whose governments seemed to be competing to top the global league table of pandemic-related deaths), people of colour were dying from the virus at disproportionately high rates. At the same time the underpaid ‘key workers’ upon whom we were now more dependent than ever – again disproportionately people of colour – had become the battering ram that those governments were using to absorb the impact of the virus, hell-bent on keeping the engines of commerce churning at all costs, even when that cost was the loss of human life. Meanwhile, giant swathes of the population who had already been clinging on by their fingertips were sent careening into financial free-fall. Floyd himself had lost his job as a security guard at a bar and restaurant affected by the pandemic-related shutdown, contracting coronavirus just weeks before his death. One pandemic had simply worsened another, the virus simultaneously highlighting and exacerbating the racial inequalities that had put George Floyd in a situation where someone might feel emboldened enough to murder him in broad daylight, in full knowledge that their actions were being captured on camera.

Cut off from friends and family, without the usual trivialities to distract and comfort and sometimes only the endless scroll of the Internet for company, we were a captive audience, an already raw nerve primed to absorb the sheer wickedness of what had happened to this man. Our phones stood poised to deliver on-demand horror at any time of day or night, whenever we summoned it in fact (which judging from my own experiences, was often). Combine all this with a population already furious at the almost criminally incompetent politicians charged with protecting us, and on high alert for injustice of any kind, George Floyd’s murder would be the kerosene on an already volatile situation, igniting an unprecedented reckoning that extended far beyond the frequently lethal bias of the criminal justice system, abruptly ripping back the bedcovers from the many systems and institutions that have anti-Blackness at their core.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.