Полная версия

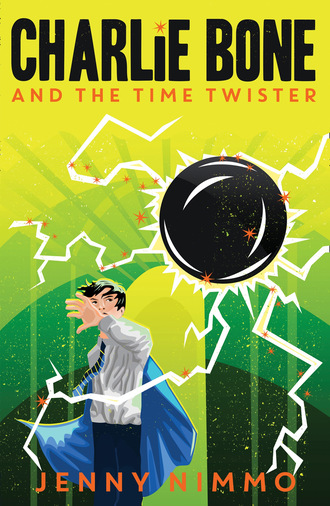

Charlie Bone and the Time Twister

The doorbell rang and Charlie ran downstairs, eager to escape the dreary packing. As soon as he opened the door, his friend Benjamin’s dog, Runner Bean, pushed past Charlie and began to shake wet snow off his back. His feathery tail sent sprays of water flying across the hall, straight into the path of Charlie’s other grandma, Maisie Jones.

‘You’d better dry that dog in here,’ said Maisie cheerfully, as she stepped back into the kitchen. ‘I’ll fetch his towel.’ She kept a special towel for Runner Bean, who was a frequent visitor.

The big yellow dog bounded after her while Charlie took Benjamin’s coat and hung it on the hall stand.

‘Are you on for building a snowman tomorrow?’ Benjamin asked Charlie. ‘Our school definitely won’t open.’

‘Mine will,’ said Charlie gloomily. ‘Sorry, Ben.’

‘Aw!’ Benjamin’s face fell. He was a small straw-haired boy with a permanently anxious expression. ‘Couldn’t you pretend to be ill or something?’

‘No chance,’ said Charlie. ‘You know what Grandma and the aunts are like.’

Benjamin knew only too well. Charlie’s aunt, Eustacia, had once been Benjamin’s minder. It was the worst two days of his life: disgusting food, early bedtimes and no dogs in bedrooms. Benjamin shuddered at the memory. ‘OK,’ he said sadly. ‘I guess I can make a snowman on my own.’

A door opened on the landing above them and a voice called out, ‘Is that you, Benjamin Brown? I can smell dog.’

‘Yes, it’s me, Mrs Bone,’ said Benjamin with a sigh.

Grandma Bone appeared at the top of the stairs. Dressed all in black and with her white hair piled high on her head, she looked more like the wicked queen from a legend than someone’s grandmother.

‘I hope you don’t intend to stay more than ten minutes,’ said Grandma Bone. ‘Charlie has to have an early night. It’s school tomorrow.’

‘Mum says I can have another hour,’ Charlie shouted up to his grandmother.

‘Oh? Oh, well, if that’s the case, why should I bother to take an interest in your welfare. I’m clearly wasting my time.’ Grandma Bone swept back into her room, slamming the door behind her.

Whether it was this door-slamming or a minor earth tremor, Charlie would never know, but something caused a small picture to fall from its hook in the hall.

Charlie had never studied the faded old photographs that adorned the walls of the dark hallway. In fact, since he had discovered his unwelcome talent, he had positively avoided them; he didn’t want to hear what a group of crusty-looking forebears had to say.

‘Well!’ exclaimed Benjamin. ‘How did that happen?’

Charlie realised this was a photograph he wouldn’t be able to avoid. As he picked it up and turned it over, he felt a strange fluttering in his stomach.

‘Let’s see!’ said Benjamin.

Charlie held out the black-framed picture. It was one of those faded sepia-coloured photographs. The glass was cracked but hadn’t fallen out, and through the cracks the boys could make out a family of five, grouped together in a garden. Behind them, the yellowed wall of a cottage could be glimpsed, and on the other side of the photo, beyond a stone wall, a small sailing boat sat on a velvety sea.

‘Are you OK?’ Benjamin glanced at Charlie.

‘No,’ muttered Charlie. ‘You know why. Oops, here we go.’ Already a thin buzz of voices was coming through to him.

It was the mother who spoke first. Henry, stand still. You’ll spoil the picture. She was a pretty woman in a lacy frock with a high collar. A brooch, like a star, was pinned just beneath her chin. A boy of about four sat on her lap, and a girl of perhaps six or seven leaned against her knee.

Beside the woman stood a man in a soldier’s uniform. He had such a merry face Charlie couldn’t imagine him with the fierce and solemn look a soldier was supposed to have. But it was the boy, standing in front of the soldier, who held Charlie’s gaze.

I can’t breathe, muttered the boy.

‘Hey, Charlie, he looks a bit like you!’ Benjamin pointed a grubby finger at the older boy.

‘Mm!’ Charlie agreed. ‘Same age as me too.’

A stiff white collar seemed to be giving the boy called Henry some trouble. It was clamped round his neck above a tightly-buttoned jacket, and almost brushed his chin. He wore knee-length breeches, long, black socks and shiny black boots.

Ouch! muttered Henry.

His mother sighed. Is it too much to ask you to stand still?

I think there’s a fly under my collar, said Henry.

At this, the soldier burst out laughing, and Henry’s brother and sister dissolved into helpless giggles.

Really, said the serious mother. I’m sure our poor photographer doesn’t find it amusing. Are you all right, Mr Caldicott?

There was a mumbled, Yes, thank you, madam, and then something fell over. Charlie couldn’t be sure if it was Mr Caldicott or the camera. The figures in the photograph swung all over the place, making Charlie feel quite dizzy.

‘You look green,’ Benjamin remarked. He led the rather shaken Charlie into the kitchen, where Maisie was rubbing Runner Bean with a towel.

‘Oh dear,’ said Maisie, taking in the situation at a glance. ‘Have you had one of your thingies, Charlie?’

‘He has,’ said Benjamin.

There was a loud sizzle as Charlie’s mother, Amy, dropped an exotic-looking vegetable into a frying pan. ‘What was it this time, love?’ she asked.

Charlie put the photograph on the kitchen table. ‘This fell off the wall when Grandma Bone slammed her door.’

‘It’s a wonder there are any doors left hanging in this house, the way that woman slams them,’ said Maisie, emptying the cracked glass into a newspaper. ‘What with the slamming and your Uncle Paton’s light bulbs, and your mum’s rotten vegetables. I sometimes think I’d be better off in a Home for the elderly.’

Everyone ignored this remark. They’d all heard it so often. Maisie wasn’t old enough to be in a Home, and she’d been told a hundred times that her family couldn’t live without her.

‘So do you know who these people are?’ Charlie pointed to the family in the black frame. Without the cracked glass, the soldier and his family could be seen more clearly.

Charlie’s mother came and looked over his shoulder. ‘They must be Yewbeams,’ she said, ‘Grandma Bone’s relations. You’d better ask her.’

‘No way,’ said Charlie. ‘I’ll ask Uncle Paton before I go to bed. Come on, Ben.’

Tucking the black frame under his arm, Charlie led Benjamin and Runner Bean up to his room. An hour playing computer games passed very quickly, and then Grandma Bone was hammering on Charlie’s door and telling him, ‘Get that dog off your bed.’ How did she guess? But then a lot of the Yewbeams had powers.

The boys trailed downstairs with Runner Bean behind them, and Charlie let Benjamin and his dog out of the front door.

He stood in the hall a moment, staring at the rectangle of pale wallpaper where the framed photograph had hung. What had caused that photo to fall? Could it really have been a door being slammed? In this house, the force at work was bound to be more mysterious.

‘Perhaps Uncle Paton will know,’ Charlie murmured. He ran upstairs.

Uncle Paton was Grandma Bone’s brother, but he was twenty years younger, and had a good sense of humour. He also had a talent for exploding light bulbs when he got near them, so he spent most of the day in his room and only went out after dark. Even in the daytime, lights were on in shop windows. At night he was not so easily seen.

Charlie retrieved the photograph from his room, and knocked on his uncle’s door, ignoring the permanent DO NOT DISTURB sign.

There was no response to his first knock, but his second drew an irritated, ‘What is it?’

‘It’s about a photo, Uncle Paton.’

‘Are you hearing voices again?’

‘’Fraid so.’

‘Come in then.’ This was said in a weary tone.

An extremely tall man with a great amount of untidy black hair looked up from a desk by the window. As he moved, his elbow sent a stack of books toppling to the floor.

‘Bother,’ said the tall man, ‘and other more rude things.’

Paton was writing a history of his family, the Yewbeams, and he needed a great many books to help him do it.

‘Where’s the photo then? Come on, show, show!’ Paton clicked his fingers impatiently.

Charlie laid the photo in front of his uncle. ‘Who are they?’

Paton squinted at the family group. ‘Ah, that’s my father.’ He pointed to the small boy sitting on his mother’s knee. ‘And that,’ putting an ink-stained finger beside the girl, ‘that’s poor Daphne who died of diphtheria. The soldier is my grandfather, Colonel Manley Yewbeam – a very merry man. He was on leave from the army. There was a war on, you know. And that’s my grandmother, Grace. She was an artist –a very good one.’

‘And the other boy?’

‘That’s . . . good lord, Charlie, he looks rather like you. I never realised that before.’

‘His hair is different. But I suppose he could have had it squashed down with something.’ No amount of squashing would keep Charlie’s thick, springy hair flat.

‘Hm. Poor Henry,’ muttered Paton. ‘He disappeared.’

‘How?’ Charlie was amazed.

‘They were staying at Bloor’s, Henry and James, while their sister Daphne was dying. It was the coldest winter for a century – my father has never forgotten it. One day, in the middle of a game of marbles, Henry just vanished.’ Paton stroked his chin. ‘My poor father. Suddenly, he was an only child. He idolised his brother.’

‘Vanished,’ murmured Charlie.

‘My father always suspected his cousin, Ezekiel, had something to do with it. He was jealous of Henry. Ezekiel was a rotten magician, but Henry was just naturally clever.’

‘Is that the Ezekiel who’s . . . ?’

‘Yes. Dr Bloor’s grandfather. He’s still there, festering away somewhere in the academy, surrounded by gas lamps and bad magic.’

‘Wow! So he’s about a hundred years old.’

‘At least,’ said Paton. He leaned forward. ‘Tell me, Charlie, these voices you hear, do they ever say anything that isn’t directly connected to that moment in time when they were being photographed?’

‘Erm, no,’ said Charlie. ‘Not yet. I don’t like looking at them for too long.’

‘Mm, pity,’ said Paton. ‘Could be interesting. Here you are then.’ He held out the photograph.

‘No thanks,’ said Charlie. ‘You keep it.’

Paton looked disappointed. ‘My father would be so happy to know a little more.’

‘Is he still alive, then?’ Charlie was surprised. He’d never seen his great-grandfather. In fact, he’d never heard anyone speak of him.

‘He’s a grand old fellow,’ said Paton. ‘He’s in his nineties now, but he still lives in that very same cottage by the sea.’ He tapped the photograph. ‘I visit him every month. If I start at midnight I can be there before sun-up.’

‘What about Grandma and the aunts. They’re his daughters, aren’t they?’

Uncle Paton made one of his here-comes-a-bit-of-scandal expressions. His thin lips compressed and his long black eyebrows arched up towards his hairline. ‘There was a rift, Charlie. A terrible quarrel. Long, long ago. I can hardly remember what caused it. For them, our father doesn’t exist.’

‘That’s awful!’ But somehow Charlie wasn’t surprised. After all, Grandma Bone wouldn’t even speak of Lyell, her only son and Charlie’s father. When he vanished, she had simply sliced him out of her heart.

Charlie said goodnight to his uncle and went to bed. But as he lay awake, trying to imagine his first day back at Bloor’s, Henry Yewbeam’s mischievous face kept breaking into his thoughts. How had he disappeared? And where did he go?

A tree falls

The temperature dropped several degrees during the night. On Monday morning, an icy wind sent clouds of sleet whipping down Filbert Street, blinding anyone brave enough to venture out.

‘I can’t believe I’ve got to go to school in this,’ Charlie muttered as he struggled through the wind.

‘You’d better believe it, Charlie, there’s the bus! Good luck!’ Amy Bone blew Charlie a kiss then turned into a sidestreet and made her way towards the greengrocer’s. Charlie ran up to the top of Filbert Street where a blue bus was waiting to collect Music students for Bloor’s Academy.

Charlie’d been put in Music only because his father had been in it. His friend, Fidelio, on the other hand was brilliant. Fidelio had saved a seat for Charlie on the bus, and as soon as Charlie saw his friend’s bright mop of hair and beaming face, he felt better.

‘This term’s going to seem very boring,’ sighed Fidelio, ‘after all that excitement.’

‘I don’t think I mind a bit of boringness,’ said Charlie. ‘I’m certainly not going in the ruined castle again.’

The bus parked at one end of a cobbled square with a fountain of stone swans in the centre. As the children left the bus, they noticed that icicles hung from the swans’ beaks and their wings were laced with frost. They appeared to be swimming on a frozen pool.

‘Look at that,’ Charlie exclaimed as he passed the fountain.

‘The dormitory’s going to be like a fridge,’ Fidelio said grimly.

Charlie wished he’d packed a hot water bottle.

Another bus had pulled up in the square. This one was purple and a crowd of children in purple capes came leaping down the steps.

‘Here she comes!’ said Fidelio, as a girl with indigo-coloured hair came flying towards them.

‘Hi, Olivia!’ called Charlie.

Olivia Vertigo clutched Charlie’s arm. ‘Charlie, good to see you alive. You too, Fido!’

‘It’s good to be alive,’ said Fidelio. ‘What’s with the Fido?’

‘I decided to change your name,’ said Olivia. ‘Fidelio’s such a mouthful and Fido’s really cool. Don’t you like it?’

‘It’s a dog’s name,’ said Fidelio. ‘But I’ll think about it.’

Children in green capes had now joined the crowd. The Art pupils were not as noisy as the Drama students and not so flamboyant, and yet when their green capes flew open, a glimpse of a sequinned scarf, or gold threaded into a black sweater, made one suspect that more serious rules would be broken by these quiet children than by those wearing blue or purple.

The tall grey walls of Bloor’s Academy now loomed before them. On either side of the imposing arched entrance, there was a tower with a pointed roof and, as Charlie approached the wide steps up to the arch, he found his gaze drawn to the window at the top of one of the towers. His mother said she had felt someone watching her from that window, and now Charlie had the same sensation. He shivered slightly and hurried to catch up with his friends.

They had crossed a paved courtyard and were now climbing another flight of steps. At the top, two massive bronze-studded doors stood open to receive the throng of children.

Charlie’s stomach gave a lurch as he passed through the doors. He had enemies in Bloor’s Academy and, as yet, he wasn’t quite sure why. Why were they trying to get rid of him? Permanently.

A door beneath two crossed trumpets led to the Music department. Olivia waved and disappeared through a door under two masks, while the children in green made their way to the end of the hall where a pencil crossed with a paintbrush indicated the Art department.

Charlie and Fidelio went first to the blue cloakroom and then on to the assembly room.

As one of the smallest boys, Charlie had to stand in the front row beside the smallest of all, a white-haired albino called Billy Raven. Charlie asked him if he had enjoyed Christmas but Billy ignored him. He was an orphan and Charlie hoped he hadn’t had to spend his holiday at Bloor’s. A fate worse than death in Charlie’s opinion. He noticed that Billy was wearing a pair of smart fur-lined boots. A Christmas present, no doubt.

They were only halfway through the first hymn when there was a shout from the stage.

‘Stop!’

The orchestra ground to a halt. The singing died.

Dr Saltweather, head of Music, paced across the stage, arms folded across his chest. He was a big man with a lot of white, wiry hair. The row of music teachers standing behind him looked apprehensive. Dr Saltweather was just as likely to shout at them as the children.

‘Do you call that singing?’ roared Dr Saltweather. ‘It’s a horrible moan. It’s a disgraceful whine. You’re musicians, for goodness sake. Sing in tune, give it some life! Now – back to the beginning, please!’ He nodded to the small orchestra at the side of the stage and raised his baton.

Charlie cleared his throat. He couldn’t sing at the best of times, but today the assembly room was so cold he couldn’t stop his jaw from shaking. The temperature had affected the other children as well, even the best singers were hunched and shivering under their blue capes.

They started up again, and this time Dr Saltweather couldn’t complain. The old panelled walls vibrated with sound. Even the teachers were doing their best. Merry Mr O’Connor threw back his head and sang heartily, Miss Chrystal and Mrs Dance smiled and swayed, while old Mr Paltry frowned with concentration. The piano teacher, Mr Pilgrim, however, did not even open his mouth.

Charlie realised that Mr Pilgrim was not standing up. He was next to Mrs Dance, who was extremely small, and being very tall himself, it was not immediately apparent that he was still sitting down. What was wrong with him? He never looked you in the eye, never spoke, never walked in the grounds like other teachers. He seemed to be completely unaware of his surroundings, and his pale face never showed the slightest flicker of emotion.

Until now.

Mr Pilgrim was staring at Charlie and Charlie had the oddest sensation that the teacher knew him, not as a student, but someone else. It was as if the dark, silent man was trying to recognise him.

There was a sudden, violent crack from beyond the window. It was so loud they could hear it above their boisterous singing. Even Dr Saltweather paused in his conducting. Another crack resounded over the snow outside, and then a tremendous thump shook the walls and windows.

Dr Saltweather put down his baton and strode to one of the long windows. When some of the children followed he didn’t bother to stop them.

‘Good lord!’ exclaimed Dr Saltweather. ‘Snow’s done for the old cedar!’

The huge tree now lay halfway across the garden; its branches broken and its tangled roots pulled clear of the ground. There was another crack as a long branch supporting the crown of the tree finally broke and, with a dreadful groan, the trunk sank into the snow.

So many games had been played under its sweeping branches, so many whispered secrets kept safe by its wide shadow. Now it was gone, and in its place there was only a wide expanse of snow and an unbroken view to the ramparts of the ruined castle. Snow encrusted the top of the walls and clung to the uneven surfaces, but the blood red of the great stones stood out ominously in the white landscape.

As Charlie stared at the castle walls, something happened. It could have been a trick of the light, but he was sure another tree, smaller than the cedar, appeared in the arched entrance to the castle. Its leaves were red and gold and yet other trees had lost their autumn colours.

‘Did you see that?’ Charlie whispered to Fidelio.

‘What?’

‘A tree moved,’ said Charlie. ‘Look, now it’s standing by the castle wall. Can’t you see it?’

Fidelio frowned and shook his head.

Charlie tried to blink the tree away. But when he looked again, it was still there. No one else appeared to have seen it. Charlie had a familiar fluttery feeling in his stomach. It always happened when he heard the voices, but this time there had been no voices.

A bang from the stage made him look back. Mr Pilgrim had got to his feet, very suddenly, knocking over his chair. He gazed over the heads of the children, into the garden beyond the window. He could have been looking at the fallen tree, but Charlie was sure he was staring past to the red walls of the castle. Had he seen the strange, moving tree?

Dr Saltweather swung away from the window. ‘Next hymn, children,’ he said as he marched back to the stage. ‘You’ll never get to your classes at this rate.’

After assembly, Charlie had his lesson with Mr Paltry – Wind. Mr Paltry was an impatient, elderly flautist. Teaching Charlie Bone to play the recorder was like trying to fill a bucket with a hole in it, he complained. The old man sighed frequently, polished his glasses, and wasn’t above whacking the recorder while Charlie was in mid-blow. Charlie reckoned that if Mr Paltry continued attacking him in this way, he would eventually lose his teeth and then perhaps he would be released from his horrible music lessons.

‘Go, Bone, go!’ Mr Paltry grunted after forty minutes of mutual torture.

Charlie went, very happily. Next it was on with the wellingtons and out into the snowy garden. In cold weather the children were allowed to wear their capes outside; in summer, capes had to be left in the cloakroom.

Fidelio was late arriving from his violin lesson, so when the two boys finally ran outside, the snow had already been trampled by three hundred children. Snowmen were being built, snowball fights were in progress, and Mr Weedon, the gardener, was trying to shoo children away from the fallen tree.

‘I want to see something by the castle,’ Charlie told Fidelio.

‘You said you didn’t want to go near it,’ his friend reminded him.

‘No, but . . . it’s like I said, I saw something. I want to know if there are any footprints.’

‘OK.’ Fidelio gave a good-natured shrug.

As they ran past the fallen cedar, Billy Raven called out, ‘Where are you going, you two?’

Almost without thinking, Charlie shouted, ‘None of your business.’

The albino scowled and shrank against the dark branches of the tree. His ruby-coloured eyes flashed behind the thick lenses of his glasses.

‘Why did you say that?’ Fidelio asked as they hurried on.

‘I couldn’t help it,’ said Charlie. ‘There’s something wrong with Billy Raven. I don’t trust him.’

They had reached the entrance to the ruined castle. The snow beneath the huge arch was clear and smooth. No one had been in or out of the ruin.

Charlie frowned. ‘I saw it,’ he murmured.

‘Let’s go in,’ said Fidelio.

Charlie hesitated.

‘It doesn’t look so bad in daylight,’ said Fidelio, peering through the arch. He bounded in and Charlie followed. They tramped across a courtyard and took one of the five passages that led deeper into the ruin.

After several minutes of shuffling through the dark, they emerged into another courtyard. That’s where they saw the blood. Or something like it. A few deep red flecks lay in the snow besidea patch of red-gold leaves.

‘The beast!’ cried Charlie. ‘Let’s get out.’

It was only when they were standing safely outside the walls again that Fidelio said, ‘It might not have been the beast.’

‘There was blood,’ said Charlie. ‘And it was the beast. It’s killed something. Or wounded it.’

‘But there were no other marks, Charlie. No sign of a fight, or footprints . . . or . . .’

Charlie didn’t wait to hear the rest of his friend’s very reasonable doubts. He raced away from the ruin as if he were re-living the long night when a yellow-eyed beast had chased him through the endless passages and cold echoing chambers. When he reached the fallen tree, he waited for Fidelio to catch up with him.

‘Clear off, you!’ said a deep voice behind him.

Already nervous, Charlie jumped and swung round. Mr Weedon’s red face appeared through the mesh of broken branches. He was wearing a shiny black helmet and Charlie caught the glint of a saw, held in the big man’s black gauntlet.

‘This tree’s dangerous,’ said Mr Weedon. ‘I’ve told you kids not to play here.’

‘I wasn’t playing,’ said Charlie. Fidelio had caught up with him and he felt a little more confident.