Полная версия

Borotbism: A Chapter in the History of the Ukrainian Revolution

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Editors Note

Introduction by Christopher Ford

1. The Ukrainian Revolution from today’s vantage point.

2. The Colonial Terrain and Social Forces of the Revolution

3. Problems of the Ukrainian Revolution

4. The Tragedy of the Russo-Ukrainian War

5. The War within the Ukrainian Peoples Republic

6. What might have been and legacy of the Borotbisty

Illustrations

Biographical Sketch of Ivan Maistrenko

Introduction by Ivan Maistrenko

1 Historical Antecedents

A. Components of Ukrainian Political Thought

1. The Russian Influence

2. The Cult of the Peasant

3. Romantic Nationalism: The Search for Self-Existence

B. Ideological Precursors of Borotbism

1. Drahomanov: The Father of Ukrainian Political Parties

2. Marxism Enters Ukraine

C. The Experience of the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party (RUP)

1. The Problem of National Liberation

2. Formulation of the National Program

3. Nationalism Splits the RUP

4. The Lesson of the Spilka

2 Origins of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries (UPSR), Predecessor of Borotbism

A. Ideological Background of the UPSR

B. The First Attempts at Formation of Ukrainian SR Groups Before 1917

C. The First SR Groups and Party Program

3 Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries in 1917

A. From the First to the Second Congress of the UPSR

1. The First Congress of the UPSR

2. The Growth and Influence of the UPSR

B. From the Second to the Third Congress of the UPSR

1. The Second Congress of the UPSR and its Turn to the Left

2. Influence of Bolshevik Ideas on the Ukrainian Revolution and on the UPSR

C. From the Third Congress of the UPSR to the Liquidation of Ukrainian Revolutionary Democracy

1. The Third Congress of the UPSR and the Party’s movement toward the Soviet position

2. The Impact of the Russo-Ukrainian War

3. Failure of a Left SR Coup and of a Right SR Government

4 The Borotbisty Under the Hetmanate

A. Worker and Peasant Opposition to the Hetman Coup

1. The Second All-Ukrainian Peasants’ Congress

2. The Second All-Ukrainian Workers’ Congress

B. The Fourth Congress of the UPSR and the Split

1. The Fourth Congress

2. Aftermath of the Congress

C. The Program of the Borotbisty

1. The Platform of the New Central Committee

2. The Weapon of Terror

3. The National Question

D. Movement of the Borotbisty Toward a Non-Bolshevik Soviet Platform

1. The Kharkiv Province Party Conference

2. The August Conference of Party Emissaries

5 The Borotbisty in Revolt Against the Hetmanate and the Directory

A. The General Uprising Against the Hetmanate

B. Disaffection with the Directory

1. Failure of the Directory’s Military and Foreign Policy

2. Peasants’ Congresses Under Borotbist Influence

C. Final Attempts to Reunite the UPSR

D. Borotbist Ties With Pro-Soviet Parties

E. Inherent Weakness of the Borotbisty

6 The Second Period of Bolshevik Rule in Ukraine

A. The Bolshevik Approach to the Ukrainian Problem

B. Borotbist Efforts to Form a Government

1. The Borotbist Central Revolutionary Committee

2 Attempted Use of Hryhoryiv’s Army

C. Implementation of Bolshevik Occupation Policy

D. Borotbism in Crisis

1. Internal Party Differences

2. Rejection by the CP(b)U

E. Joint Action Against Hryhoryiv

1. Bolshevik Detente with the Borotbisty

2. Hryhoryiv’s revolt against the Bolsheviks

7 Borotbisty in the Denikin Underground

A. Formation of the Ukrainian Communist Party (Borotbisty): UCP(B)

B. Two Views on the Formation of the UCP(B)

1. The “Dual Roots” Theory

2. The Bolshevik Argument

C. Borotbist Opposition to the Denikin Regime

1 The Borotbist Underground in Kyiv

2. Borotbist Activity Among the Partisans

8 The third Period of Bolshevik Rule in Ukraine

A. Bolshevik Re-Examination of the Ukrainian Problem

1. Bolsheviks Face To Face with the Ukrainian Problem

2. The Guiding Hand of Lenin

B. Bolshevik Resolutions

1. The Russian Bolsheviks

2. The Ukrainian Bolsheviks

3. The Borotbist-Ukrainian Bolshevik Agreement

C. Final Borotbist Attempt To Organize A Ukrainian Red Army

1. Interlude with Makhno

2. Alliance With Ataman Volokh

3. The Trotsky Order

D. The Growth and Dissolution of the UCP(B)

1. The Spread of Borot’bism Among the Masses

2. The Bolshevik Ring Around the Borotbisty

3. Dissolution of the UCP(B)

E. Divers Views on the Dissolution of the Borotbisty

9 The Borotbisty in the CP(b)U

A. The CP(b)U and the UCP(b) Compared

1 Composition of the CP(b)U

2. Composition of the UCP(b)

B. A Letter From a Ukrainian SR Emigre

C. Borotbism Versus Philistinism in the CP(b)U

D Shumskism

Appendix 1 Reminiscences of the Borotbist Organization in the District of Kobeliaky

Appendix 2 Biographical Sketches of Individual Borotbisty

Appendix 3 Platform of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries: The Present State of Affairs and Party Tactics (approved by Central Committee on June 3, 1918)

Appendix 4 Draft Decree on Encouraging the Development of Culture of the Ukrainian People

Explanatory Note to the Decree

Text of the Decree

Appendix 5 Memorandum of the Ukrainian Communist Party (Borotbisty) to the Executive Committee of the Third Communist International

I

II

IV [sic]

Special Supplement Soviet Responses to Maistrenko’s Borotbism

Bibliography

A. General Works

B. Congresses and Conferences

1. Communist International

2. CP(b)U

3. RSDRP(b) and RCP(b)

C. Articles

D. Letters, Speeches, Draft Projects, Resolutions

SPPS Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society

Copyright

Levko Maystrenko

15 December 1925–20 June 2010

Dedicated to the memory of Levko without his support and solidarity the republication of his father’s book would not have been possible.

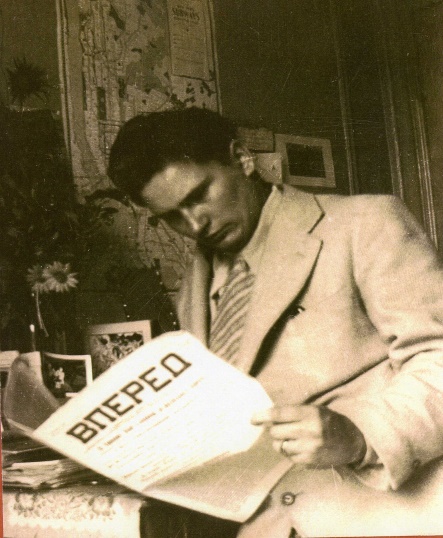

Ivan Maistrenko

28 August 1899–18 November 1984

Acknowledgements

The author records his affectionate gratitude to his friend Edward Dune, a noble fighter for freedom in Soviet Russia, who died in Paris on January 21, 1953. Mr. Dune assisted the author in locating rare source materials in the Bibliotheque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine and the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris.

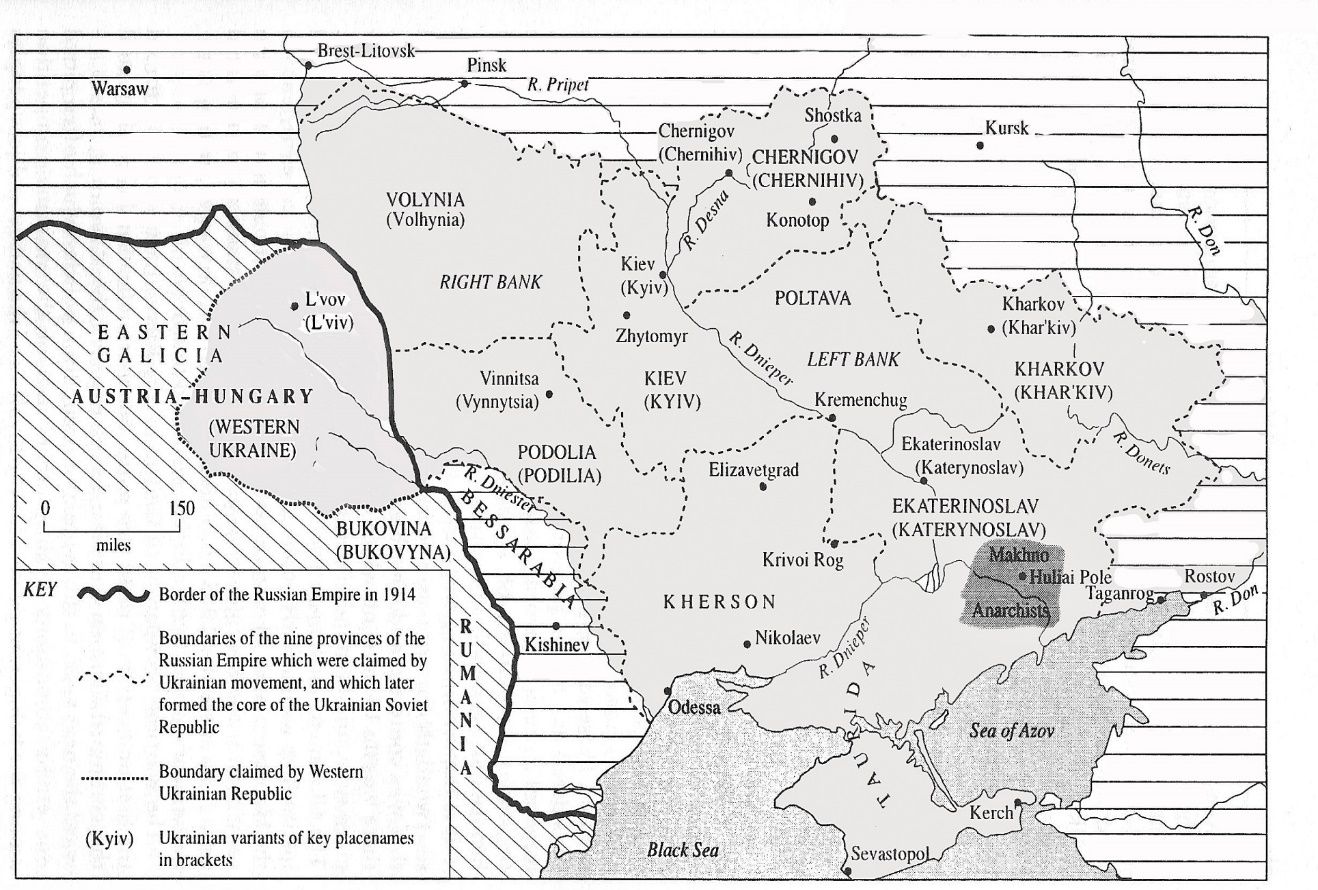

The author wishes to thank the Research Program on the U.S.S.R., through whose assistance this study was made possible. Special thanks go to Dr. Alexander Dallin, former Associate Director of the Research Program, for suggesting the theme of the present study. The author thanks Dr. John S. Reshetar, Jr. of Princeton University for reading the manuscript, Dr. George S.N. Luckyj of the University of Toronto, who made the original translation, and Mr. Ivan L. Rudnytsky for his assistance in the translation and editing. Mr. Peter Dornan of the Research Program edited the text; the author is particularly grateful to him for this work. He also thanks Mr. Nelson Glover, who prepared the map.

The author’s thanks are extended to the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the United States and in particular Mr. Volodymyr Mijakowskij for his and their cooperation in providing photostatic copies of source materials, and to Mr. Hryhory Kostiuk and Mr. Jurij Lawrynenko for reading the biographical material and supplying additional data.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Columbia University Press and Mr. Bertram D. Wolfe for permission to reprint excerpts from copyrighted material in Mr. Wolfe’s article “The Influence of Early Military Decisions upon the National Structure of the Soviet Union,” which appears in The American Slavic and East European Review, New York, Vol. IX, No. 3, October 1950, pp. 169–179.

Foreword

MARKO BOJCUN

This new edition of Ivan Maistrenko’s 1954 study of the Ukrainian Revolution is a welcome and timely contribution to the English language literature. Appearing on the centenary of that epochal event that has come to be known as “the Russian Revolution” it provides valuable insights into its multinational and regional complexities and the diversity of the communist movement itself. Christopher Ford has also given us a new introduction here that will help the reader situate Maiestenko’s work in the broader context of a modern Ukraine emerging from an era of declining European imperialisms and ascendant movements for universal emancipation.

Maistrenko was not just a witness, but an active participant in the revolution and civil war of those years in Ukraine. He challenges several misleading generalisations and stereotypes that have come to dominate the historiography of 1917 and its aftermath. First, he shows on the basis of the Ukrainian case that this revolution was not Russian alone, nor just a working class achievement, but a richly diverse “festival of the oppressed” that broke out all over the Empire and drew into action millions of peasants and workers, nations and national minorities subjugated by Tsarism and Russian imperialism. It was not merely the arena of professional revolutionaries pursuing state power in Petrograd and Moscow, but the efforts of workers, soldiers and peasants in cities, towns and villages alike trying to overcome the major obstacles to their self-emancipation: the War, land hunger, the collapse of industry brought on by the War and national oppression.

Maistrenko illuminates this tumultuous process in Ukraine, focussing in particular on the rural population, the landless peasantry and the agricultural proletariat. He traces the evolution of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries, which became the largest political party by far in Ukraine at the head of repeated mobilisations of the peasantry in 1917 and during the civil war. He shows how and why the UPSR, a party with roots in the populist and anarcho-socialist traditions, was shaken and split by the events of that period and eventually yielded the Borot’bisty, an indigenous Ukrainian communist movement.

Maistrenko’s work helps us to understand how the Ukrainian Revolution differed from the Russian as well as how they intersected, and how the Bolsheviks could come to hold state power in Ukraine at the end of the Civil War only by occupying it militarily and subordinating all three communist parties then operating in it to the Russian Communist Party headquartered in Moscow.

The Ukrainian Communist Party (Borot’bisty), as opposed to the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine, fought for an independent Ukrainian soviet republic allied through federation with the Russian soviet republic. It sought membership as an independent party in the Third (Communist) International. The Borot’bisty subsequently played a critical role in the life of their country after their own party was dissolved and they joined the official CP(B)U. They championed Ukraine’s cultural revival and its quest for greater political autonomy within the Soviet Union. Practically all of them perished in Stalin’s purges in the 1930s.

Ivan Maistrenko was one Borot’bist who survived to tell their story, a chapter in the history of the Revolution that might otherwise been buried in Stalin’s mass graves. Moreover, he has left us with more than a political history, but also a personal one with recollections of events he witnessed on the ground and of comrades with whom he worked in the underground, the peasant brigades and the insurgent republic of his own locality. Maistrenko was fluent in Ukrainian and Russian, as well as German by the time he wrote this history. That gave his access to the original documentary sources when he came to compose this study in the early 1950s.

We can now look back on the epoch-changing upheaval of the Revolution a hundred years ago through Maistrenko’s unique examination of its eruption in Ukraine.

Editors Note

This new edition of Ivan Maistrenko’s Borotbism has been reformatted and slightly re-edited from the original 1954 edition. Which was republished in the original format in 2007. A number of aspects of the original text have been updated such as the transliteration of Kiev which is published here as Kyiv. This edition includes not only a new introduction and foreword but also a biographical essay of Ivan Maistrenko and in supplement a review of Soviet responses to Borotbism. A number of illustrations have been added including rare pictures provided by Ivan’s son Levko Maystrenko and his granddaughter Ulyana. The title of the book has been slightly changed from it original Borotbism a Chapter in the History of Ukrainian Communism to Borotbism a Chapter in the History of the Ukrainian Revolution.

NOTE TO 1954 EDITION

1 Events occuring between February (March) 1917 and February 1 (14), 1918 are dated in both old style and new style.

2 The boundaries of geographical regions referred to in the text in the pre-revolutionary period are not necessarily co-extensive with boundaries established by the Soviet regime.

3 The Ukrainian word “rada” has been rendered English by the word council whenever councils in Ukraine are under discussion, except in the case of the Ukrainian Central Rada; the Russian word “sovet” also meaning council had been rendered in its English form soviet whenever councils in Russia are under discussion, except in the case of the Russian Council of Peoples Commissars. Soviet has also been used in the phrase Soviet platform, whether this applies to Russia or Ukraine.

Introduction

CHRISTOPHER FORD

Volodymyr Vynnychenko, one of the most well-known Ukrainian leaders in the 20th century, coined the phrase vsebichne vyzvolennia—“Universal liberation”.1 By this he meant the “Universal (social, national, political, moral, cultural, etc.) liberation” of the worker and peasant masses. This striving for “such a total and radical liberation” represented the “Ukrainian Revolution” in the broad historical sense. However the expression the “Ukrainian Revolution” may also be used in the narrower sense, of the great upheavals aimed at this object, the most noteworthy of which marked the years 1917–1920.

According to Vynnychenko, the “Universal current” which strove to realize this historical tendency of the revolution comprised the most radical of the socialist parties, the Ukrainian Social Democratic Workers’ party (Independentists), or Nezalezhnyky, the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries-Borotbisty and the oppositional currents amongst the Bolsheviks in Ukraine.

The Ukrainian Revolution cannot be understood without sharing the hopes, disappointments and aspirations of its participants. One such participant in those dramatic events that form the subject of this book is its author Ivan Maistrenko. His book tells the story of the revolution through the history of one element of that “Universal current”—the Borotbisty.2 One of the first significant accounts of the revolution in English, Borotbism is a unique work whose republication comes at a time of increased interest in Ukraine. Yet amidst the array of materials now available to the reader, there remains a deficiency with regard to the pivotal role of Ukrainian Revolutionary socialism in those years.

This problem of the revolution’s historiography is not new and its continuation makes this book as important today as when it first appeared in 1954. Maistrenko’s work remains the principal study of the Borotbisty, the majority left wing of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries—the largest party of the revolution.3

1. The Ukrainian Revolution

from today’s vantage point.

Ivan Maistrenko’s Borotbism compels us to return to this ‘rebirth of a nation’ not merely to mark the 100th anniversary of the Ukrainian Revolution but also in recognition that a review of the past is essential to grasp the challenges of the present. This can be seen in the changed circumstances in which Maistrenko’s book is presented in contrast to when it first appeared in 1954.4 Since the Euromaidan in 2014 and the Russo-Ukraine war there has been a surge of interest in Ukraine; this is a progressive development it is however coupled with new depths of retrogression as regards attitudes to the Ukrainian question.

Recent years have demonstrated how Russia’s imperial past continues to echo into what was presumed to be the “post-imperial” present; we have witnessed a revival of a narrative advanced by the White movement during the Civil War. Its advocates base their interpretation of the Ukrainian question on a set of key principles:

1 “Great Russia, “Little Russia” and “Belarus” are three branches of the one Russian people,

2 Russian language and culture is the common achievement of one, leading Russian people;

3 “Little Russia”, i.e. Ukraine, is an inseparable part of a unitary Russia;

4 ; the idea of a separate Ukrainian nation is manufactured by foreign powers for the dismemberment and weakening of Russia.5

Interpretations of the Ukrainian question by contemporary Russian leaders are essentially the same; they have equipped the current form of the Russian state power with ideas inherited from their Tsarist ancestors. The reburial of General Denikin in 2005 with full military honors at Moscow’s Donskoi monastery was an apt symbol of this reconnection with Empire.

That Denikin secured Western sponsors for the Russian nationalist cause is understandable; that Vladimir Putin can harness support of the contemporary European far-right is no surprise.6 What is significant, and perhaps surprising to some, is the support by sections of the left for restoring the Tsarist colony in Ukraine of Novorossiya (New Russia).7 Stalinism was imbued with the Russian nationalist tradition, and whilst current neo-Stalinism assists Kremlin foreign policy with its veneer of an “anti-fascist struggle in Ukraine”, the Russian oligarchic elite make no pretense of a communist camouflage in acting as heir and guardian of the imperialist policies of the Tsars.8

Maistrenko’s Borotbism challenges this retrogression; it repudiates the falsification and revision of the array of self-appointed experts on Ukraine that have surfaced, and who reduce the Ukrainian Revolution of 1917–21 to a series of failed states sponsored by foreign powers.9 It reasserts the history of the revolution as a struggle for social and national emancipation by the Ukrainian people themselves.

Such conflicts over the history of Ukraine are not new and often become focal points for the greater conflict between Ukrainian nationalism and Russian chauvinism; the contemporary controversies are themselves intimately linked to the recurrence of the Ukrainian question with it domestic and international considerations. The current context in which the Ukrainian question is posed is one that Maistrenko foresaw with remarkable accuracy in the 1950’s.10 That imperialist expansion was generating a future challenge to Moscow’s hegemony, where each national bureaucracy would one day come into conflict with the Russian bureaucracy. In addition he foresaw that the Soviet bureaucracy would welcome the restoration of private-capitalism, provided it ensured their continued privilege. It was this re-composition of a nouveau nomenklatura that emerged after the Ukrainian resurgence of 1989–1991 attained formal independence.11

This is the root of the current complexities in which the big business power of the oligarchs has been the dominant influence on the politics and economy of Ukraine. Whilst in the face of western rivalry, Russia has continued to seek to protect its business interests and influence in Ukraine, which is viewed from the strategic perspective as part of the “greater Russian world” within the “near abroad” of post-USSR space.12 Maistrenko considered “Stalinism, the Modern Form of Russian Imperialism”; under Putin this has taken on a new form of appearance.13 Motivated by what it views as its national security interests Russia’s rulers continue to adopt methods of encroachment to protect their regime from destabilizing influences and have revived the old “gendarme of European reaction”.14 This role of policing of the territory of empire was deployed following the Euromaidan in 2014.

Euromaidan saw the mobilization of wide sections of society aspiring to greater democracy, equality and human rights. This political revolution toppled President Yanukovych, driving a wedge into the neo-colonial power relations Russia exercised in Ukraine. In response, the deposed Donetsk clan of oligarchs and those connected to them; concerned for their vested interests instigated the separatist movement. This revanchist movement converged with the interests of Russia’s elite, the Kremlin organizing, arming and directly reinforcing its proxy forces.15 The ensuing war in Donbas in 2014 has echoes of the 1914 occupation of eastern Galicia by the Russian Imperial Army. Viewed as the piedmont of the Ukrainian movement, the Tsar declared it “a Russian land from time immemorial”. With support of the small groups of local Russian nationalists they set about forcibly Russifying the populace and persecuting Jews. Putin has proved no more attractive to Ukrainians than the Tsar, and the reach of Russian ultra-nationalists has suffered a long historical retreat from Lviv to Luhansk.