Полная версия

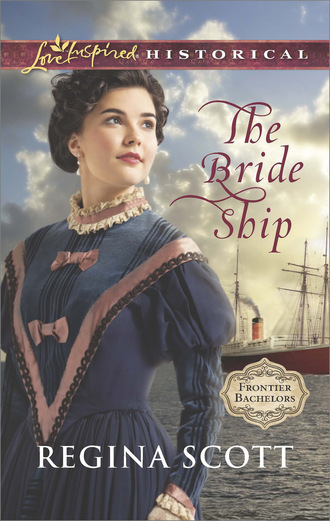

The Bride Ship

But the other passengers were more discouraged. Two men and their families, disappointment chiseled on every feature, had already been escorted downstairs to identify their belongings, along with a few crying women. One, Mr. Debro reported, had barricaded herself in a stateroom, refusing to leave. Others threatened retribution.

Allegra was different. She must have left Gillian below with friends, for when it was her turn, she glided into the room alone, head high, smile pleasant. Her gaze swept the space, resting briefly on Clay. Her look pressed a weight against his chest. She passed him without comment and went straight to the captain, pulling a piece of paper from the pocket of her cloak and holding it out as if allowing him to kiss her hand.

Captain Windsor didn’t even glance at her offering as Mr. Debro came to stand beside him. “I need a ticket, Mrs. Banks, not your correspondence with Mr. Mercer.”

She was paler than the first Boston snowfall, her profile still. “If you read that correspondence, Captain, you will see that Mr. Mercer acknowledges payment for my passage. I was promised a spot for me and my daughter. I paid Mr. Mercer six hundred dollars.”

Six hundred dollars. A princely sum for most people, but a pittance for his family.

“You may have paid Mr. Mercer,” Captain Windsor replied. “However, there is no record of Mr. Mercer relaying the monies to Mr. Holladay, the owner of this fine vessel. Have you any way to pay for your passage, madam?”

She shifted on her feet, setting the black fringe on her skirts to swinging. “I gave Mr. Mercer all I had. I’ve been washing dishes to pay for our board until the ship sailed.”

Clay stiffened. How was that possible? Frank must have provided for her. Clay hadn’t been surprised to hear that his younger brother had stepped in as soon as Clay had stepped out. Frank had been in love with Allegra for years. Besides, the marriage settlement had been considerable. He’d seen the papers, even if he’d left before signing them.

But if Allegra couldn’t pay her way, did that mean he had an opportunity to return her to Boston, after all?

“We have sufficient help in the kitchens,” Captain Windsor said across from him. “I’m afraid I have no choice but to send you back. Fetch up Ms. Madeleine O’Rourke, Mr. Debro.”

The purser frowned and glanced around Allegra toward Clay. “Mr. Howard? Will you be escorting the lady?”

Because Allegra had used her maiden name, the captain couldn’t know she was Clay’s sister-in-law. Clay rose, but she took a step closer to the captain.

“Please,” she said, voice low. “Don’t let him take me back. I’ll do anything.”

The tremor in her voice shook him. Had Frank’s death made Boston so impossible for her, being reminded of him everywhere she looked? He couldn’t conceive that his mealymouthed cousin Gerald had caused such heartache. The Allegra Banks he remembered would have silenced Gerald with a look.

Whatever its source, her pain propelled him to her side, forcing her gaze to meet his. For a moment, he saw fear looking back at him.

Father, what happened to her?

As if she was determined not to allow him to help, she took a breath, collected herself and became the sophisticated Allegra Banks he remembered.

“I don’t require your escort, Mr. Howard,” she said. “I know my way downstairs.”

“I’m not offering to escort you,” Clay said. “I’m offering to pay your way.” He was taking the biggest risk of his life, disappointing his family once again. Forgive me, Father, if I’ve mistaken Your direction, but I cannot help thinking this is the right thing to do.

As she stared at him, Clay turned to the captain, pulled out his pouch and counted off the last of his certificates. He’d have little to live on the rest of the trip, but if that meant a chance to help Allegra and Gillian, he could make do.

The captain glanced between the two of them. “Under the circumstances, Mrs. Howard,” he said, “I should ask you if you are willing to accept this man’s money for your fare.”

She had to know what accepting such a gift might mean, that she was somehow under Clay’s protection. Once more he could see the calculations behind her blue eyes.

“Have you pen and paper, sir?” she asked the captain. “I would have you draw up a contract between me and Mr. Howard.”

“That isn’t necessary,” Clay started, but she whirled to face him, eyes blazing.

“It is entirely necessary,” she scolded him. “I will not accept money from you without a contract. And I will pay you back every cent, even if I have to work the rest of my life to do so.”

He wanted to argue. Why couldn’t he do her this service? After all, the good citizens of Boston thought he’d been the one to abandon her, when he and Allegra had been promised for ages. But she knew the truth. She’d been the one to send him away.

He nodded. “Very well, Mrs. Howard. Let’s not trouble the good captain now. I’m sure there’s pen and paper belowdecks.”

She drew a deep breath, turned to the captain and inclined her head. “I accept Mr. Howard’s offer, then. If there is nothing else, gentlemen? I’d like to settle my daughter before we sail.”

Captain Windsor handed the certificates to the purser. “You’re free to go, Mrs. Howard. Mr. Debro will give you your stateroom number. I hope the trip is to your liking.”

She inclined her head again. “Come along, then, Mr. Howard. Let’s settle this between us.” She made her way from the room, head still high, steps measured, never doubting he’d be right on her heels, like a trained spaniel.

She thought a simple contract would settle things between them. He was certain it would never be that simple. He caught her arm before she could start down the stairs. “I don’t want your money, Allegra.”

Her chin was so high he thought her neck must hurt from the strain. “And I don’t want your help, Mr. Howard. But it appears that neither of us is going to get our wish.” She took a deep breath. “I’ll give you ten dollars a month once I’m employed in Seattle.”

She was a hopeless optimist. He couldn’t imagine what work she’d be qualified to do in Seattle, and she’d be lucky to make that much a month regardless of the job she took. Wasn’t this further proof that the wilderness was no place for her?

“It will take years for you to pay me off,” he pointed out. “I’ll give you better terms.” He lowered his head to meet her gaze. “You don’t want me around. That’s clear enough. But if you allow me to become acquainted with my niece, I’ll call us square.”

She sucked in a breath. “Spending time with Gillian? That’s it?”

Clay straightened. “That’s it. Though it goes without saying that I expect the two of us to try to be civil to each other for the three and a half months it will take to reach Seattle.”

She raised her brows. “Three and a half months being civil to you, Mr. Howard? You ask too much.” She pulled away from him and clattered down the stairs.

* * *

The nerve of the man! Allie stomped down the stairs, fury rising with each footfall. Clay Howard didn’t fool her for a second. All that talk about acquainting himself with his niece only to claim he wanted Allie to be “civil.” Her days in Boston society had taught her that when a gentleman paid so much money to support a lady, he generally expected a great deal more than civility—fawning gratitude, to say the least.

She did not intend to be civil about it.

Nor was she inclined to grant him any favors. She would find a way to pay him back. She might not be an excellent cook like Maddie or a trained nurse like Catherine, but she could sew a fine hand. All those years of embroidering pillowcases and tatting lace had to count for something. Mr. Mercer had assured her she could support Gillian by sewing for other families. She’d merely add Clay’s money to her list of expenses.

She felt him behind her on the stairs, but she refused to turn and look. Too bad she couldn’t simply pretend he wasn’t there. Her mother and his would have had no trouble doing so. Anyone in Boston society trembled to receive a cut direct from Mrs. Banks or Mrs. Howard. To her shame, Allie had used the gambit more than once on the men who had courted her, looking through them as if they weren’t there, refusing to hear their pleas for forgiveness for whatever they thought had annoyed her. She wasn’t going to treat anyone that way now.

But she could not help remembering the last time she’d seen Clay. She’d known she’d marry Clayton Howard since she was seven and overheard her mother talking with his. Clay had been thirteen then, an impossibly heroic figure in her eyes, and she’d spent much of the next ten years following him around with Frank beside her.

While her parents and the Howards complained that Clay was too wild, too undisciplined, Allie and Frank had looked up to him, tried to ape everything he did. She had a scar on her knee from where she’d been thrown trying to ride as well as he did. Frank had spent a week trying to master the way Clay tipped his top hat with such a flourish. Clay had just smiled at their antics and gone about his business. She’d never understood why his parents hadn’t appreciated him as much as his younger brother.

But when Allie turned seventeen, things changed. Boys who couldn’t be bothered to notice her suddenly vied for her attention. She was the belle of Boston, her parlor stuffed with suitors. Instead of her following Clay around, hoping to catch his eye, he was the one who had to compete for a moment with her. Her popularity had been exhilarating, and she’d let it go to her head.

Then came the night he’d confessed his dreams to her. Her mother had been hosting a ball, the house crowded with the very best of Boston society. Clay had looked so handsome, so commanding, in a tailored coat of midnight black that was the perfect complement to her pearly-white ball gown. The string quartet had been playing a lilting waltz, and she’d hoped Clay would take her in his arms and whirl her about the floor. Instead, he’d led her out onto the back veranda overlooking the gardens scented by her mother’s prized roses.

Clay had put his arms around her, sheltering her as moonlight bathed their faces, and she’d shivered in delight to find herself the center of his attention at last. But his words had not been the declaration she’d hoped.

“I’m done with Boston, Allegra,” he’d said. “I’m heading west, and I want you to come with me.”

She pulled away from him, fluttering her fan even as her pulse stuttered. “Clay,” she said, “you cannot mean it. Boston is our home. Everyone we know is here.”

“And everyone here knows me,” he countered. “That wild Howard boy. I feel as if I can’t breathe. Out west I can be my own man, a man you can be proud to call husband.”

Her heart soared. He wanted her beside him, his partner, his love. It was everything she’d ever wanted. And yet...

“I’d be proud of you here, too, Clay,” she assured him. “I know you and your father don’t see eye to eye, but if you talk to him...”

His hand sliced through the air. “I’ve talked to him too many times. I can’t be the man he expects, Allegra, and if I stay under his thumb I’ll be no man at all.” He caught her close, spoke against her temple. “Come with me. For ‘I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the heart’s affections and the truth of imagination.’”

She loved it when he quoted the old poets such as Keats. Clayton Howard knew all the ways to turn a phrase and take away her objections. But this time, instead of sweeping her away, his touch raised a panic.

She’d just come into her own. She was somebody. How could he ask her to leave?

She pushed him back. “Clay, be reasonable. Everyone knows there’s nothing but wilderness and savages beyond the Adirondacks. Boston society is the best in the nation. If you’d just try a little harder, I’m sure you could fit in.”

“That’s the problem,” he said, his warm voice cooling. “I don’t want to fit in, Allegra. I want more. I thought you’d want more, too.”

She could not imagine what more there might be. Boston ladies married well, bore children, entertained family and friends, supported worthy causes. How could she do that from some backwoods hovel?

“There now,” she’d said as if soothing a petulant child. “I’m sure we can discuss this another time when we’ve both had a chance to think about it.” She’d linked her arm with his. “They should be playing a polka soon. I know you like that dance.”

He’d touched her face with his free hand, fingers tracing the curve of her cheek. “I would take any opportunity to dance with you, Allegra. My feelings won’t change.”

She’d thought he meant his devotion to her would never change. But two days later, he’d left Boston, and she hadn’t set eyes on him again until they’d met on the pier. It seemed Clayton Howard’s devotion was to his future, not theirs. Her parents and his had encouraged her to swallow her disappointment and marry Frank. Frank, who had never argued with her, who had been her dear friend as long as she could remember. And so a month later, she and Frank had wed amid the smiling approval of Boston society, a society she could no longer abide.

She didn’t remember reaching the bottom of the stairs. The touch of Clay’s hand on her arm drew her up.

“Be reasonable, Allegra,” he murmured, offering a smile that would once have set her to blushing. “I have no intention of being an annoyance. But I think we both agree it’s my duty to protect you.”

“Duty?” Allie shook her head. “This journey was my choice, sir. You have no duty to protect me from my future. I can handle myself on the frontier. You forget, my ancestors civilized Boston.”

Clay snorted, dropping her arm. “Is that your reason for going? You think the fine citizens of Seattle need to be civilized? There isn’t a fellow in the territory who will thank you for it.”

“On the contrary,” Allie insisted. “Mr. Mercer assured us that we will be welcome additions to the city, serving to bring it to its full potential. He, sir, has a vision.”

Clay rolled his eyes. “Spare me. I’ve spent the last hour watching how easily Mercer’s plans fell apart. No one seemed to know who had paid and who hadn’t. It wouldn’t surprise me if Mercer had skipped town with your money. You’ve been duped, Allegra. Admit it.”

Anger was pushing up inside her again. Why were her ideas never taken seriously? Why was she always the one who had to bend to another’s insistence?

“Just because you dream small, Clay Howard,” she told him, “doesn’t mean other men have the same narrow vision. And neither do I. I will pay you back every penny, I will allow you to spend time with Gillian, but I won’t listen to another word against our plans. Do I make myself clear, sir?”

Any Boston gentleman who had borne the brunt of her anger would have begged her pardon, immediately and profusely. Clay merely lowered his head until his gaze was level with hers. Something fierce leaped behind the cool green.

“Don’t expect me to jump when you snap your fingers, Allegra,” he said. “I paid your passage because this trip seems to be important to you. But I won’t nod in agreement like a milk cow to everything you say. I’ve been to Seattle. I know the dangers of the frontier. I owe it to Frank to protect you from them.”

As if in agreement, the Continental shuddered, and a deep throb pulsed up through the deck. Allie was tumbling forward, her feet not her own. She landed against something firm and solid—Clay.

His arms came around her, and she found herself against his chest. His gaze met hers, seemed to warm, to draw her in. She couldn’t catch her breath. Once, she’d dreamed of his embrace, his kiss.

Heat flared in her cheeks at the memory, and she pulled herself out of his arms. “You owe Frank nothing, Clay Howard. And you owe me less. If you insist on coming to Seattle with us, you’d better remember that.”

Chapter Four

Clay paused while Allegra continued into the salon. In truth, he felt as if the jolt of the ship starting forward had knocked some of the breath out of him. It had been a long time since he’d held Allegra in his arms, and, for the sake of his sanity, it ought never to happen again. Hadn’t he learned by now that he was no match for Boston society?

In fact, it was the suffocating chill of Boston high society that had driven him west, far from everything he’d ever known. He couldn’t regret it. He’d climbed mountains, tops shimmering with snow, ten times the size of Beacon Hill. He’d crossed rivers wider than the Charles and more swiftly flowing. He’d met Indian chiefs with as much pride as his late father, lady prospectors with more presence than his mother. Riding across the vast prairies, he’d realized how small he was and how big the God he served.

It was God’s urging that had propelled him back to Boston when Clay had received the letter telling him about Frank’s death. Like the prodigal son, he’d come to make amends. He wanted to explain to his mother why he’d left, to make sure Allegra was doing all right with Frank gone. He’d taken a room at Boston’s finest hotel, Parker’s; bought a new suit of clothes; even hired a carriage to take him to his family home.

No fatted calf awaited him. Though his father had died several years ago, Clay had hoped his mother would receive him. But the person waiting for him in somber black in the elegant parlor was his cousin Gerald.

“A great deal has changed since you left, cousin,” he’d said, his icy blue eyes staring across the space, every blond hair pomaded back from his narrow face. “With Frank gone, I’ve had to take up the responsibilities you refused to honor.”

Clay’s hands had fisted at the sides of his fancy suit. “I’m here now. Where’s my mother?”

“Indisposed.” Gerald had all but sneered. “And quite unwilling to see you. It is my unhappy duty to inform you of the fact.”

“She has no interest in where I’ve been?” Clay challenged. “What I’ve done?”

“None,” his cousin said. “It doesn’t matter where you’ve been. It matters that you weren’t here. We all know it should have been you in that field near Hatcher’s Run.”

Of course it should have been him. He was the oldest, the better rider, the best shot. He’d had the advantage of a year of military training in a school that specialized in turning willful boys into disciplined men. Frank hadn’t had to attend that school. Frank was the good son, obedient, a friend to all who knew him. He didn’t know why his brother had gone to war, when so many of the wealthy families paid a poorer boy to fight in their son’s stead when their son had been drafted. According to the friend who had written Clay, Frank had gone down protecting others who had been wounded, considerate even to the end.

Clay raised his head. “If you’ve accepted responsibility for my mother and Frank’s widow, I applaud you. Just know that I’m willing to help, whatever they need.”

His cousin’s tight smile was the only answer.

The trip back to the hotel had been mercifully short, for all Clay’s emotions ran higher than the horses on the hired coach. He’d been throwing his things back in his satchel when the bellman came to tell him that a Mrs. Howard was waiting for him downstairs.

Immediately his mind had gone to Allegra, and he pushed past the fellow in his rush to see her. But the woman who perched on one of the scarlet upholstered chairs in the hotel’s ornate parlor was gray haired, her bearing cool, composed in her silver-colored gown trimmed in black lace and jet beads.

“Mother,” he said, going to her.

Gillian Howard’s thin lips trembled, but she did not offer her pale cheek for his kiss. “Clayton. I thought that was you when I looked out the window. You came home.”

Was he mad to hear hope behind the words? “I wanted to talk to you,” he confirmed, sinking onto a chair beside her. “I wanted to see Allegra.”

Before he could continue, she reached out and clutched his arm, fingers tight against his sleeve.

“That’s why I’m here, son,” she said, calm voice belying her hold on him. “Allegra is missing, and you’re the only one who can bring her home.”

She’d gone on to explain her daughter-in-law’s fascination with Asa Mercer’s story about struggling Seattle and the chance of making it a paradise on earth.

“It’s the same ridiculous pie-in-the-sky tale that sent you west,” she’d lamented, dabbing at her eyes with a lace-edged handkerchief. “You came back...you must know the truth. Tell her this hope in Seattle is a lie. Convince her to come home. Please, Clay, she’s all I have left!”

Her pain had touched him just as Allegra’s had today, yet some part of him hurt that his mother could not consider him part of the family. “I thought Gerald was taking care of everything for you,” he couldn’t help commenting.

She’d lowered her gaze even as she tucked her handkerchief into her reticule. “Gerald has been a great blessing to me. He is very good about seeing that the family carries on. I cannot ask this of him.”

But she could ask it of him. Gerald was a gentleman; Clay had thrown off the label. His cousin might not be willing to do all it would take to retrieve Allegra. His mother obviously believed Clay had fewer scruples. Though Clay liked to think he was still an honorable man for all he’d chosen a different path than the one his parents had picked out for him, he could not argue that he was his mother’s best tool for the job. He was more than ready to do Allegra a service, particularly if it meant saving her from the mistakes he’d made.

Now he snorted. And wasn’t he doing a jolly good job of saving Allegra? Instead of sending her home to Boston, he’d aided and abetted her in running away! Shaking his head at his own behavior, he entered the lower salon. Those passengers who had not yet been assigned staterooms were clustered around a hatch at the end of the room. Allegra and her daughter were looking on, but he couldn’t tell whether they were curious or concerned. He pushed himself to the center, where a pretty, petite blonde was struggling with a brass latch embedded in the floor.

On seeing him, she put on a winsome smile. “Please, sir,” she said sweetly, “would you mind helping me with this?”

The others made room for him, their gazes expectant, as if he were about to open a fabled treasure cave. Clay was more suspicious.

“What is this?” he asked, positioning himself over the hatch.

“Access to the coal bin, sir,” she replied. “I was told by Mr. Mercer to open it immediately when we set sail out of quarantine. He said it was very important.”

Clay couldn’t understand why anyone needed to see into a dark, dusty coal bin, but he had to admit to curiosity as to why Mercer had thought it so important. He bent to haul on the ring, and the hatch opened. People leaned around his arm, peering into the gloom. He could see Allegra and her redheaded friend exchanging frowning glances.

“It’s safe now, Mr. Mercer,” the blonde called into the void. “You can come out.”

Allegra stiffened in obvious shock, while others put their hands to their mouths. Coal-dusted fingers waved above the edge of the hole, and Clay bent to tug Asa Mercer to the floor of the salon. He was a slender man, not yet thirty, with a solemn face and a brisk manner. Now his curly reddish hair and whiskers were speckled with black, his long face striped with grime. He tugged down on his paisley waistcoat and beamed at those around him.

“The coal is well stored and sufficient for the first leg of our journey,” he reported as if he’d merely climbed into the bin to inspect it. “It appears we are under way. I look forward to a fine voyage, a very fine voyage.”

Allegra stared at him a moment, then turned her gaze to Clay’s. Very likely, they’d reached the same conclusion.

She had no one to rely on but him, and she had every right to be concerned.

* * *

It was not the most auspicious start to their journey. While many of the women welcomed their benefactor, Allie couldn’t shake the image of Mr. Mercer rising from the coal bin. This was the man in whom they’d placed their trust?