Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

After the second world war our knowledge increased rapidly. Mr J. L. Davies began in 1947 by investigating the breeding season in the comparatively small group found off the Pembrokeshire coast, notably on Ramsey Island. In two subsequent years, 1950–51 a small group from London led by Dr L. Harrison Matthews F.R.S. continued the work there and enlarged it to cover the nutrition of the pup and some basic aspects of reproduction. Quite independently in 1951 a group from the Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle-upon-Tyne Natural History Society led by Mrs Grace Hickling began to weigh and tag pups in the hope of tracing the movements of the moulters when once they had left the Farne Islands. Their success was immediate and the idea caught on. I had been with the group on Ramsey Island in 1951 and in the next two years tagged as many pups as I could. In the last of these years I was joined by Dr K. M. Backhouse who had taken part in the Farne Island work and who has continued to work with me both in the field and the laboratory ever since.

In 1954 and 1955 I went to Shillay in the Outer Hebrides to follow up a report of a disproportionate number of bull seals seen there by Dr J. Morton Boyd (who afterwards became Director of the Scottish Nature Conservancy). This led to interesting observations in pre-breeding behaviour, a field which is still largely open for the investigator. In 1956–57 Dr Backhouse joined me in observations in the Inner Hebrides, on islets off Oronsay, again to cover the pre-breeding period and the establishment of a breeding community on the rookery.

All these observations were connected with the breeding season, as, in fact, had been all the pre-war observations. In 1954 Dr Backhouse and myself decided to begin investigations during the winter and spring using the Ramsey Island group as our base as being within reasonable touch of London, travelling down over Friday night and back on Sunday night. This was dictated by our teaching duties during term time, but could be altered and ameliorated during the Christmas or Easter vacations. Our success was very limited since only two weekends a month were suitable on account of tides, and winter gales, either before or during the weekend, prevented us or the seals from reaching the island on many occasions.

Three very significant results emerged however; first that there was a delay in the development of the embryo (January 1956) and secondly that there was a small but quite significant number of births of spring pups (April 1956) and thirdly that this was associated in the Pembrokeshire group with large haul-outs of moulting bulls in the spring (April 1957).

Meanwhile quite unknown to us Prof. J. D. Craggs, an electronics engineer in the University of Liverpool, and N. F. Ellison, both active members of the Liverpool Natural History Society, turned their attention from the birds of Hilbre Island, off the Wirral peninsula, to the seals which gathered at low-water on the West Hoyle Bank a mile or so farther out to sea. These had previously not been very numerous and had always been thought to be common seals. They turned out to be grey seals and a series of observations made almost every fortnight throughout the year over five years (1952–57) showed not only that the numbers were increasing, but that they fluctuated regularly during the year. They were observing the obverse of those investigating the breeding grounds and thereby made a most valuable contribution.

To estimate the numbers of grey seals on and around the breeding grounds has always been an objective of observers and one of the difficulties has been the tendency of the seals to use small islands and skerries within a considerable radius from the breeding centre itself. Thus it was physically impossible to make a simultaneous count over the whole area, and this was imperative if the count was to have any significance. The use of an aeroplane had been tried during the breeding season in 1947 when J. L. Davies knew the numbers of seals from a ‘ground count’ in Pembrokeshire. It showed that little reliance could be placed on such observations unless the ground was fairly clear or only pups were being counted. Adults and moulters are too cryptically coloured to be easily recognisable. The only group which showed a promise of success was that of the Farne Islands where the haul-out points are necessarily limited to the outermost of the Outer Farnes and are not in fact far from the breeding islands of the Outer Farnes. From 1958 onwards monthly ground counts were made there by Mrs Hickling and Dr J. Coulson and so gave a picture the converse of Craggs and Ellison’s.

In 1958 breeding of grey seals was discovered on Scroby Sands off Great Yarmouth and appeared to point to an increase and spread of the Farne Island group. In this year, too, North Rona became a National Nature Reserve so that in 1959 an expedition comprising Dr J. Morton Boyd and Dr J. Lockie of Nature Conservancy (Scotland), Mr J. MacGeogh, the honorary warden of North Rona and Sula Sgeir and myself (the only Sassenach!) landed there on October 1st to stay for at least three weeks and make periodic censuses of the pups and other observations. Similar expeditions have gone almost every year since with varying personnel to keep a check on the numbers. Dr Boyd also organised over several years observations from scattered points over the west coast of Scotland to see whether data could be collected indicating movements of seals to or from the breeding centres. Some interesting facts have emerged from this too and from aerial photographs of some islands to which access is extremely difficult and rarely possible.

But all this was field work and without a background of knowledge based on the examination of material in the laboratory many of the deductions which one would like to have made could only be very tentative. One of the outstanding problems related to the time-scale of the grey seal’s life. Several views had been put forward in the past without any firm basis. This is very dangerous because such ideas are often repeated as though they were well established facts. Here was such an instance. Davies accepted the view that a 12-year life span was normal for the female grey seal and had based his calculations of the total south-western group population on this. There neither was then, nor is now, any way of determining the age of a seal in the field. At that time there was not any way of doing so even if the carcase of the animal was available for examination. ‘How long do they live?’ or ‘How old is it?’ are two of the commonest questions asked about animals and they are almost the most difficult to answer. To find a method was, therefore, of first priority.

Researches on the Pribilov fur-seal and several other mammals had shown during the post-war years that the deposition of some of the hard parts of the teeth was periodic and could be interpreted in terms of years, just as one can determine the age of some fish from their scales. By the late 1950’s I had satisfied myself that the layers of cement on the outside of the root of the teeth could, after some practice, be so used in the grey seal with reasonable accuracy. All that was now wanted was more material.

During these years complaints from the salmon fishers, both rod and net, had been growing. Also from the white fish industry came reports that the occurrence of cod-worm was very much on the increase and the grey seal was blamed as the vector of this parasite while the Farne Island group were thought to be the centre of the culprits. Consequently the grey seal became of economic importance. The carcases of seals killed at the salmon nets along the east coast of Scotland were then made available and a great deal of material began to come in. It was not very well preserved of course and it was highly selective consisting only of those seals whose bodies could be recovered; if they were too heavy to handle they were not brought ashore. However, it was a start. Added to this an investigator, Mr E. A. Smith, was appointed in 1959 jointly by the Development Commission (on the Fisheries side) and by Nature Conservancy; he soon found that there was a group of grey seals (as well as common seals) in Orkney. Tagging soon showed that they were as guilty as the Farne Islands ones for depredations on the salmon of the Scottish east coast. Moreover the group was a very large one and could supply material in sufficient quantity for research without fear of seriously depleting the stocks. Of the other two known large groups, Farne Islands and North Rona, one was a sanctuary under the National Trust and the other a National Nature Reserve. Orkney and later Shetland then supplied most of the really valuable material. Further, when some degree of cull was decided upon during the breeding season, the statutory protection afforded the grey seal since the early 1930’s was lifted and for the first time we were able to obtain a sample of a breeding population in October 1960. Using the already discovered method of age determination an entirely new light was thrown on the age structure of the population, on the sexual life of both bulls and cows and many of the field observations previously made began to fall into place and to make sense.

Many more minor problems have been worked on since, particularly by Mr Smith in the field and by Dr Backhouse and myself in the laboratory. None of us however has failed to take part in the other type of work involved, since cross-fertilisation of ideas between field and laboratory is essential for orderly progress to be made. There remained of course a number of outstanding puzzles which will be mentioned in the pages which follow.

Within the last few years however, there have been developments which promise a continuation of systematic and sophisticated research, not only on the grey seal, but also on the common. The establishment of the ‘Seals Research Unit’ at Lowestoft under the National Environment Research Council with Mr Nigel Bonner in charge assisted by a small team of very active and resourceful zoologists has already shown what can be done using more modern equipment and the importance of prolonged co-ordination in work which must of necessity be scattered over a wide geographical area. Some of these results will be referred to later on.

It is now necessary to define certain words which will be used to describe collections of grey seals when found on land. In the past the term ‘colony’ has been used in so many different senses that it has become almost meaningless and I shall not employ it. Before appropriate alternative words could be found it was necessary to know something about the seals and how the world population was organised. Already it has been shown that there are three major units and I propose to refer to these as ‘forms’. This term does not have the precise meaning taxonomically that ‘sub-species’ would carry but it does suggest that we are dealing with sub-units of the world population which are distinct on biological grounds as well as geographical. So little is known as yet of the break-down of the Baltic and western Atlantic forms that it is only possible to supply terms to describe the composition of the eastern Atlantic. Here first we must distinguish between the centre of breeding and places where, in the non-breeding season, the seals may haul out. The breeding centre will consist of ‘rookeries’ where pups are born and mating takes place. In addition there are collections of seals associated with the rookeries to which reference will be made later. The important biological fact of the rookery in relation to seal populations is that it is the origin of the population. If therefore the females may use one of several adjacent rookeries, the products of these rookeries must be considered as a single population arising from a ‘group’ of breeding centres. Here I propose the use of the word ‘group’ to describe a subdivision of the eastern Atlantic population which appears to behave as an entity and to possess some definable characteristics, either geographical or biological or both, which separate them from other ‘groups’.

In some instances we still do not know enough to be certain whether we are dealing with one or two groups. For example, a number of grey seals breed on the north Cornish coast, there is an occasional birth on the Isle of Lundy and many more breed on the islands and coast of Pembrokeshire and Cardiganshire. Are we justified in thinking of these as a single working unit or ‘group’, or are there two? To add to the difficulty, just across the St George’s Channel, grey seals breed on the Irish islands of the Saltees and farther north on Lambay Island off Dublin. Should these be separated or included? What sort of evidence is there? We know that there are no breeding sites in the northern part of the Irish Sea but in the area of the Mersey Bight many can be seen in the non-breeding period of the year as well as on Bardsey Island off the Caernarvonshire coast and around Holyhead Island. Their numbers wane during the period when the Pembrokeshire seals are breeding but some, instead of going south, might well go west or south-west and breed on the Irish coast. Many a young seal in its first grey coat, only a month or so old, marked in Pembrokeshire, has turned up on the coast of Ireland even as far west as Galway Bay. Do they come back to the Welsh coast when they are mature, or do they join the Irish breeding seals? So far we have no definite answer and I prefer to think of a south-western group which would include all those I have already mentioned on the west and south coasts of Ireland, the Irish Sea, west Wales and Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly and Ushant off the Brittany coast.

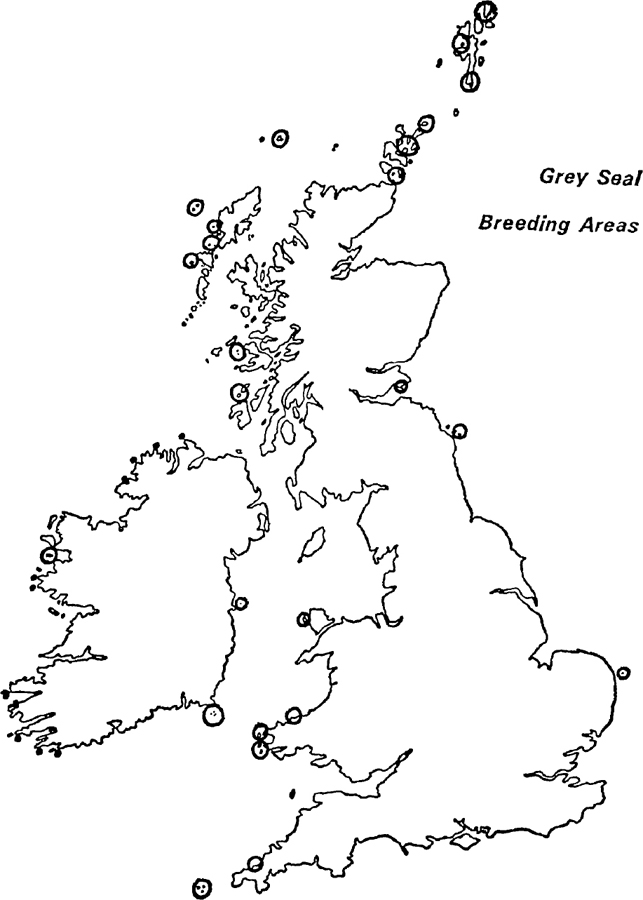

Other ‘groups’ for which there is some evidence are: Southern Hebridean, comprising breeding areas on the Treshnish Isles (off Mull), in the islands around Oronsay such as Eilean nan Ron and Ghaoidmeal and the occasional birth recorded on Rathsay Island off Antrim, Northern Ireland; Outer Hebridean, covering Gaskeir, Shillay, Coppay, Haskeir, Causamell, St Kilda and North Rona, including Sula Sgeir; Orkney and Shetland; North Sea comprising the Farne Islands, Isle of May and Scroby Sands (Figs. 9 and 10).

The islands detailed here are noted for the presence in the breeding season of rookeries but there are other kinds of collections of grey seals particularly in the non-breeding season to which descriptive names have been given. Where the character of the collection is unknown it may simply be called a ‘haul-out’. This may be qualified by the addition of an adjective as in a ‘fishing haul-out’. Such a haul-out is temporary in the sense that although it may be regularly used the number of the individuals may vary from day to day and no one seal will necessarily remain there for very long. A fishing haul-out is one where there are collected a sample of the grey seal population using that area for fishing, as a temporary resting or basking site. The West Hoyle Bank off the Wirral peninsula is a good example (Pl. 22). The seals there may vary from a very few (less than a dozen) to upwards of 200 depending on weather and tide. When not hauled-out they are probably feeding in the northern part of the Irish Sea. In some groups the absence of widely distributed haul-out sites often results in the same islands or groups of islands being used both as rookeries and for fishing haul-outs. It is rare however for exactly the same site to be used for the two purposes.

FIG. 9. Distribution of the grey seal in British waters. Coasts where sightings have been recorded are shown in thick black line.

Another type of haul-out is the ‘moulting haul-out’. These occur only in the later part of winter or early spring and consist predominantly of one sex or the other (Pl. 14). Such sites may be also used at other times as fishing haul-outs, but during the moult the numbers are often very great amounting to several thousand in the larger groups such as Orkney and Shetland. The number of these sites appears to be quite small, one or two alternative sites for use in different weather conditions sufficing.

As the breeding season approaches there are pre-breeding ‘assemblages’, not on the actual ‘rookeries’ or breeding sites, but usually adjacent. The number of seals there diminishes as the breeding season gets under way, but are replaced often on different skerries or islands by ‘reservoirs’ of grey seals. More will be said about the characteristics of these haul-outs later.

It cannot be too strongly emphasised that all of these haul-outs, including even the breeding rookeries, are biased samples of the population of the group. Never are all the members of a group collected together even within the land area covered by a number of breeding rookeries and reservoirs. Consequently there is no easy way to estimate the total number of grey seals in a group even if it were possible to carry out a simultaneous census on all land sites. The question ‘How many grey seals are there?’ is often asked by the layman. It is one of the most difficult to be answered by the scientist.

Some description of the geography involved is now desirable. Fraser Darling drew attention to the very variable conditions in which the grey seal breeds and considered that the land rookeries of North Rona represented the ancestral habit. Davies, who was a geographer as well as a zoologist, believed that the various breeding behaviours were forced on to the grey seal by the geographical features. Certainly it must be admitted that since the last glacial period the grey seal will have spread northward and that the most southern localities now used would have been the first to be occupied in these islands, if in fact they were ever entirely deserted. On the whole the evidence supports Davies. Certainly to understand the differences in behaviour the geography must be taken into account (Fig. 10).

SOUTH-WESTERN GROUP

This is the most widely dispersed group and although a considerable amount is known about the Welsh section, little information is available about either the Cornish or Irish sections apart from the barest outlines of the breeding localities. Throughout this group there is a tendency for the breeding sites to be small and contained in sea caves; they can hardly be dignified by the term rookeries as rarely more than a dozen cows pup in any one of the caves. Towards the middle of the breeding season pupping spreads to the beaches. These are either rocky or stony and backed by steep cliffs. Generally they are narrow so that at high water the sea may be lapping the base of the cliffs (Pl. 2). If this is not true at neap tides, it certainly is at springs. Several authors have referred to this group as the ‘cave breeding seals’. Throughout the area will be found ‘seal caves’, the name may be used locally or may be ‘official’ and appear on Ordnance Survey maps. In many of the caves there are beaches only towards the back of the caves so that investigation can only be made from the sea. This feature has added to the difficulties of investigation for few, if any, of the local boatmen are willing to risk their craft close in among the rocks and currents of such exposed coasts. The steep cliffs also present problems if only of time in making a descent and return. However, they do provide vantage points for observation and counts of white coated pups can be made from the cliff-tops above the narrow beaches. At the sea caves observation can only be made of the cows bobbing about in the water. Observations over open beaches indicate that for every six pups on the beach about five cows can be seen as a maximum at any one time with their heads above water. One or more are usually off on a swim. This ratio can be applied to the caves to arrive at an approximate count of pups. Neither method allows one to make an accurate assessment of the age of the pup or its sex. This can only be done by ground investigation at close quarters. It is not surprising, therefore, that there is less accurate numerical information about the grey seals of this area than of any of the other groups. Another feature which adds to the difficulties of obtaining even the basic information is the length of the coastline involved. The island sites off the Welsh and Irish coasts are comparatively easy. As long ago as 1910 when the Clare Island survey was undertaken off Galway a reasonably complete account was given by Barrett-Hamilton of the breeding sites there. Similarly Lord Revelstoke (1907) describes the cave sites on Lambay Island, while more recently Davies gave an excellent record of the breeding season on Ramsey Island off Pembrokeshire. But the small widely distributed coastal beaches of Cornwall, the Welsh mainland and south-west Ireland have only been cursorily surveyed within the last few years.*

FIG. 10. Distribution of the grey seal in British waters. The areas where breeding rookeries are known to occur are shown by black circles. On the Irish coast the exact localities are not known but possible sites are indicated by black spots. The size of the circle is not indicative of the numbers of seals involved in breeding.

The narrow entrances to the caves and the shallow beaches both militate against the building of a social structure on shore during the breeding season. In this group the organisation takes its form in the sea and consequently the behaviour of both bulls and cows is very different from that found in the more northern groups. Over many weeks of observation maintained during the hours of daylight, I have only seen bulls ashore on four occasions and on two of these they were at the water’s edge. Only in the most secluded coves can more than a few cows be seen at any one time, and then most will be seen to be suckling their pups and will have newly come ashore.

Little is known in the area occupied by this group of the use made of skerries and islands for non-breeding purposes. Haul-outs, presumably fishing ones, are usual on Lundy, the exact site being dictated by the weather. Skokholm and other Pembrokeshire islands and skerries have records of non-breeding haul-outs. Ramsey Island which provides one of the principal centres of breeding sites also has a moulting haul-out site in the late winter and spring. This beach, Aber Foel Fawr, which is inaccessible except by boat, but can be fully observed from a neighbouring cliff, is also used as a ‘reservoir’ during the breeding season as Davies has pointed out. Lockley has published a photograph of a beach with a similar moulting haul-out, but does not mention where it is. Since upwards of 200 seals, mostly of one sex, have been seen on each of these two beaches, it is possible that these are the only moulting sites for the Cornish-Pembroke-Wexford section of the group.

From what has been said about the difficulties of obtaining an accurate count of the pups and also from the absence of precise information about parts of the area occupied by this group, it will be readily appreciated that an estimate of the total number of grey seals in the group is very difficult to make. Estimates of the Welsh section made by Davies and, independently, by myself suggest that there were about 1,000 of all ages and both sexes connected with the breeding grounds of west Wales and the southern Irish Sea. This may now be exceeded. For Cornwall, the Scilly Isles and the west of Ireland the estimates cannot be much more than inspired guesses and would possibly add a total of 1,000+, making 2,000+ in all.

Despite the vagueness of this total it can be confidently said that the numbers are on the increase. Reference has already been made to the fishing haul-out on the West Hoyle Bank, off the Wirral peninsula, where Craggs and Ellison made counts of the grey seals. Quite apart from the seasonal variations, which were reported annually, their figures showed a steady increase year by year. Since the publication of their paper (1960) the number continued to increase but has levelled off in the last five years. This could, of course, mean that the Mersey Bight has become a more popular fishing ground, but independent observations, without however the numerical precision of Craggs and Ellison’s data, show an increase on Bardsey Island and on the west Wales breeding sites.