Полная версия

Phantom Terror: The Threat of Revolution and the Repression of Liberty 1789-1848

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers,

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins 2014

Copyright © Adam Zamoyski Ltd 2014

Adam Zamoyski asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

Jacket image:The Massacre of Versailles, October 5, 1789, engraving. French Revolution, France, 18th century (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007282760

Ebook Edition © October 2014 ISBN: 9780007352203

Version 2015-10-05

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Illustrations

Map: Europe in 1789

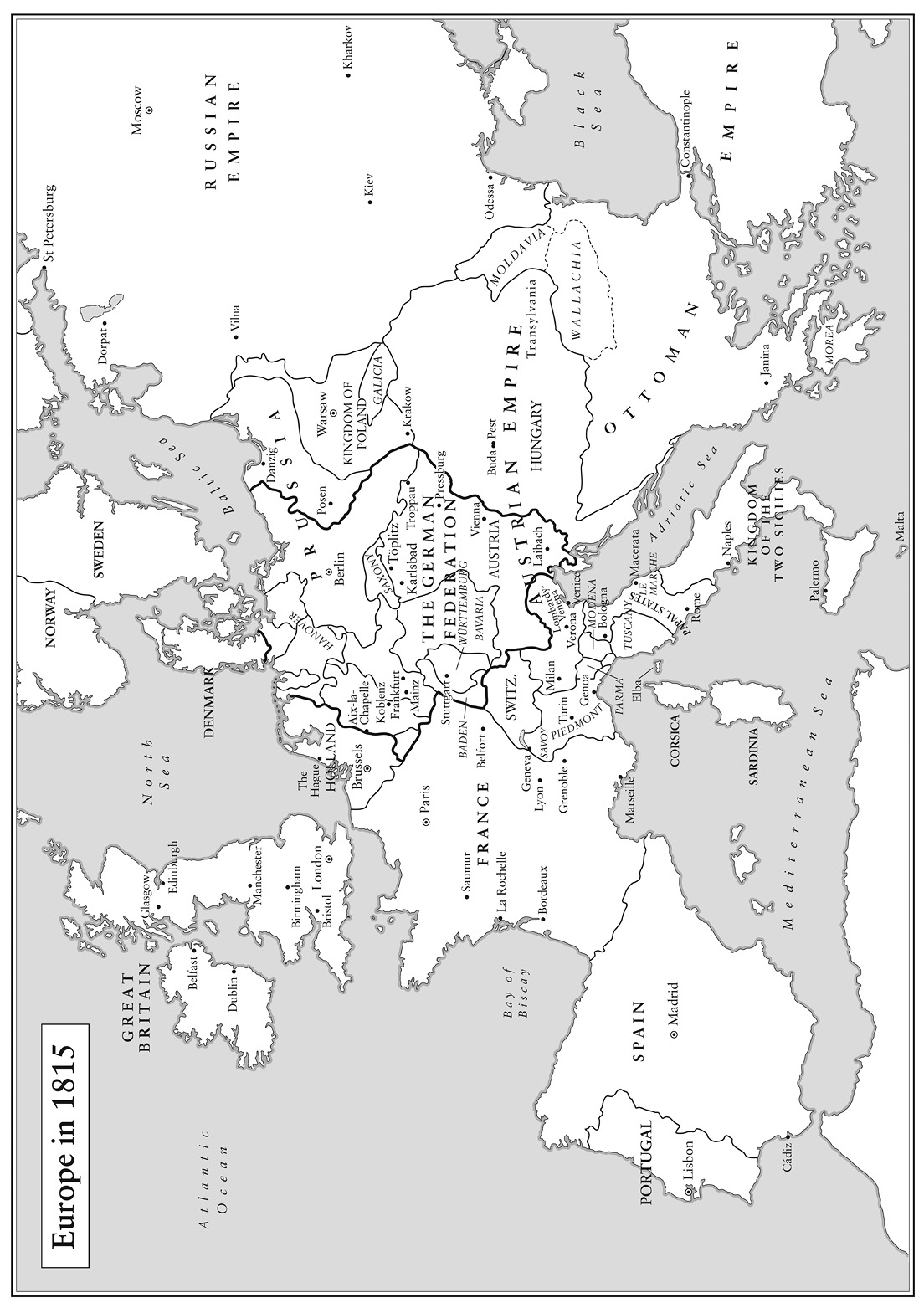

Map: Europe in 1815

Preface

1 Exorcism

2 Fear

3 Contagion

4 War on Terror

5 Government by Alarm

6 Order

7 Peace

8 A Hundred Days

9 Intelligence

10 British Bogies

11 Moral Order

12 Mysticism

13 Teutomania

14 Suicide Terrorists

15 Corrosion

16 The Empire of Evil

17 Synagogues of Satan

18 Comité Directeur

19 The Duke of Texas

20 The Apostolate

21 Mutiny

22 Cleansing

23 Counter-Revolution

24 Jupiter Tonans

25 Scandals

26 Sewers

27 The China of Europe

28 A Mistake

29 Polonism

30 Satan on the Loose

Aftermath

Notes

Picture Section

Sources

Index

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Illustrations

Philosophy Run Mad, or a Stupendous Monument of Human Wisdom, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1792. (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Tsar Alexander I. Portrait by George Dawe. (© English Heritage Photo Library/Bridgeman Images)

The Holy Roman Emperor Francis II. Portrait by Johann Baptist Edler von Lampi, 1816. (© DHM/Bridgeman Images)

William Pitt the Younger. Portrait by John Hoppner. (Rafael Valls Gallery London/Bridgeman Images)

An explosion in the rue Saint-Nicaise in Paris on 24 December 1800, the work of French royalists and Pitt’s agents bent on assassinating Napoleon. (The Art Archive/Alamy)

Joseph Fouché, the prototype of the modern secret policeman. Engraving by Philippe Velyn, c.1810. (akg-images)

The murder of August von Kotzebue at Mannheim on 23 March 1819. (akg-images)

The Wartburg Festival, held on 18 October 1817 to celebrate the tercentenary of the Reformation and the fourth anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig. Woodcut c.1880. (akg-images)

Prince Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, chancellor of Austria. Portrait by Josef Danhauser. (© DHM/Bridgeman Images)

Two Men Contemplating the Moon (detail), by Caspar David Friedrich, 1819. The painting exercised the Prussian police, as the two men are wearing the banned ‘Old German’ costume and might be plotting. (Fine Art/Alamy)

The Radical’s Arms by George Cruikshank, published 13 November 1819 by George Humphrey. (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Drawing of an ‘anti-cavalry machine’. (The National Archives, Kew. TS II/200)

The Duke of Wellington, arch-reactionary and apologist for the ‘Peterloo Massacre’. Attributed to Thomas Lawrence. (Huntington Library/Superstock)

The Peterloo Massacre, 16 August 1819. By George Cruikshank, published 1 October 1819 by Richard Carlile. (Manchester Art Gallery/Bridgeman Images)

Radical Parliament!! 1820. By George Cruikshank, c.1820. (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

The murder of the duc de Berry on 13 February 1820. By Louis Louvel. (RA/Lebrecht Music & Arts)

A document purporting to be a copy of the hieroglyphs used by a secret society. (Documents from Archives nationales, Paris, F/7 Police Générale 6684, Sociétés secrètes, Dossier 4)

A meeting of the Carbonari, as imagined by a contemporary illustrator. (Private Collection/Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images)

A drawing supplied to the French police by an informer, supposedly of daggers being forged by French and Italian secret societies for the murder of European monarchs. (Documents from Archives nationales, Paris, F/7 Police Générale 6684, Sociétés secrètes, Dossier 4)

General Alexei Arakcheev, by an anonymous artist, 1830s. (© Fine Art Images/AGE Fotostock)

Russian political prisoners in the dungeons of the Schlusselburg fortress. (Everett Collection Historical/Alamy)

The Peter and Paul fortress in St Petersburg. (RIA Novosti)

Count Alexander von Benckendorff, head of the notorious Third Section. Portrait by Yegor Bottman. (Fine Art Images/AGE Fotostock)

Tsar Nicholas I. Portrait by Vassily Tropinin, 1826. (© Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy)

Russian troops parade following the suppression of the Polish insurrection of 1830. Painting by Nikanor Grigorievich, 1837. (akg-images)

The remains of the ‘machine infernale’ used by Giuseppe Fieschi in his attempt to murder King Louis-Philippe. (Roger-Viollet/REX)

Infortunées victimes du 27, 28 et 29 Juillet 1830, by Grandville. (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The folkloric and nationalist jamboree held at the castle of Hambach in May 1832. After a drawing by F. Massler. (akg-images)

Bombarding the Barricades, or the Storming of Apsley House, published February 1832 by J. Bell. (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Barrikade in der Burggasse zu Altenburg am 18 Juni 1848. (akg-images)

Political prisoners at Trier following the suppression of the local revolt in 1848. By Johann Velten, 1849. (akg-images/De Agostini Picture Lib./A. Dagli Orti)

Patrol of the Vienna National Guard on 14 March 1848. (akg-images)

The Great Water Snake as it Appeared to Many in 1848. Published 30 December 1848. (akg-images)

General Survey of Europe in August 1849, by Ferdinand Schroeder, 1849. (akg-images)

Preface

The Battle of Waterloo, Napoleon’s final nemesis, also marked the defeat of the forces unleashed by the French Revolution of 1789. This had challenged the foundations of the whole social order and every political structure in Europe. It had opened a Pandora’s Box of boundless possibilities, and horrors: the sacred was profaned, the law trampled, a king and his queen judicially murdered, and thousands of men, women and children massacred or guillotined for no good reason. The two and a half decades of warfare that followed saw thrones toppled, states abolished and institutions of every sort undermined as the Revolution’s subversive ideas swept across Europe and its colonies.

The reordering of the Continent by those who triumphed over Napoleon in 1815 was intended to reverse all this. The return to a social order based on throne and altar was meant to restore the old Christian values. The Concert of Europe, a mutual pact between the rulers of the major powers, was designed to ensure that such things could never happen again.

Yet the decades that followed were dominated by the fear that the Revolution lived on, and could break out once more at any moment. Letters and diaries of the day abound in imagery of volcanic eruption engulfing the entire social and political order, and express an almost pathological dread that dark forces were at work undermining the moral fabric on which that order rested. This struck me as curious, and I began to investigate.

The deeper I delved, the more it appeared that this panic was, to some extent, kept alive by the governments of the day. I also became aware of the degree to which the presumed need to safeguard the political and social order facilitated the introduction of new methods of control and repression. I was reminded of more recent instances where the generation of fear in the population – of capitalists, Bolsheviks, Jews, fascists, Islamists – has proved useful to those in power, and has led to restrictions on the freedom of the individual by measures meant to protect him from the supposed threat. A desire to satisfy my curiosity about what I thought was a historic cultural phenomenon gradually took on a more serious purpose, as I realised that the subject held enormous relevance to the present.

I have nevertheless refrained from drawing attention to this in the text, resisting the temptation, strong at times, to suggest parallels between Prince Metternich and Tony Blair, or George W. Bush and the Russian tsars. Leaving aside the bathos this would have involved, I felt readers would derive more fun from drawing their own.

In order to avoid cluttering the text with distracting reference numbers, I have placed all notes relating to quotations and facts contained in a given paragraph under a single one, positioned at the end of that paragraph. For the sake of simplicity, I have used the Gregorian calendar throughout when referring to Russian events and sources. I have not been as consistent on the transliteration of Russian names, using those versions with which I believe the reader will be most familiar – the Golitsyn family have appeared in Latin script for over three hundred years as Galitzine, and I have therefore stuck to that spelling, which they still use themselves. Translations of quotations from books in languages other than English are mine, with some assistance in the case of German.

Lack of time prevented me from spending as much of it in archives as I would have liked, and I was therefore obliged to seek the assistance of others. I should like to thank Pauline Grousset for following up some of my leads at the Archives Nationales in Paris; Veronika Hyden-Hanscho for pursuing various trails in the Viennese archives on my behalf; Philipp Rauh for reading through a large number of books in German; Thomas Clausen for his enthusiastic trawl through the archives in Stuttgart, Wiesbaden and Darmstadt; Hubert Czyżewski for his diligent work in the National Archive at Kew; Sue Sutton for further searches on my behalf at Kew; and Jennifer Irwin for her research in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland.

I would also like to extend my thanks to Chris Clark for his guidance on matters German, to Michael Burleigh for moral support at a moment when the surrealism of my subject began to make me doubt my own sanity, to Charlotte Brudenell for drawing my attention to the eruption of Mount Tambora, and to Shervie Price for reading the manuscript.

I owe a great debt of gratitude to my editor Arabella Pike, for her patience and her extraordinary faith in and enthusiasm for my work; to Robert Lacey, whose meticulous and intelligent editing is unmatched; and to Helen Ellis, who makes the uphill task of promoting books a pleasure. I am also deeply indebted to my agent and friend Gillon Aitken, for his unflagging support. Finally, I would like to thank my wife Emma for her patience and understanding, and her love.

Adam Zamoyski

May 2014

1

Exorcism

On Wednesday, 9 August 1815, HMS Northumberland weighed anchor off Plymouth and set sail for the island of St Helena in the South Atlantic, bearing away from Europe the man who had dominated it for the best part of two decades. All those who had lived in fear of the ‘Ogre’ heaved sighs of relief. ‘Unfortunately,’ wrote the philosopher Joseph de Maistre, ‘it is only his person that has gone, and he has left us his morals. His genius could at least control the demons he had unleashed, and order them to do only that degree of harm that he required of them: those demons are still with us, and now there is nobody with the power to harness them.’1

The man in question, Napoleon Bonaparte, former Emperor of the French, had said as much himself. ‘After I go,’ he had declared to one of his ministers, ‘the revolution, or rather the ideas which inspired it, will resume their work with renewed force.’ As he paced the deck with what the captain of the seventy-four-gun man-of-war, Charles Ross, described as ‘something between a waddle and a swagger’, he appeared untroubled by any thought of the demons he was leaving behind. He was more concerned with his treatment at the hands of the British to whom he had surrendered, who refused to acknowledge his title. He was addressed as ‘General Buonaparte’, and accorded no more than the honours due to a prisoner of that rank. Two days earlier, protesting vigorously, he had been unceremoniously transferred from HMS Bellerophon, which had brought him to the shores of England, to the Northumberland, in which Rear-Admiral Sir George Cockburn, commander of the flotilla that was to convey him to his new abode, had hoisted his flag. He had been subjected to a thorough search on coming aboard and his baggage was turned over – Captain Ross noted that he had ‘a very rich service of Plate, and perhaps the most costly and beautiful service of porcelain ever made, a small Field Library, a middling stock of clothes, and about Four Thousand Napoleons in Money’, which was confiscated and sent to the British Treasury. Dignity had never been Napoleon’s strong suit, and his attempts to elicit the honours due to his imperial status were doomed. Nor did he elicit much sympathy outside the group of devoted followers who had elected to share his captivity. On first meeting him, Captain Ross found him ‘sallow’ and ‘pot-bellied’, and thought him ‘altogether a very nasty, priest-like looking fellow’. Closer acquaintance as they set sail did nothing to soften his view. Admiral Cockburn described his habit of eating with his fingers and his manners in general as ‘uncouth’.2

Napoleon and six of his entourage, which, with domestics and the children of some of his companions, totalled twenty-seven, dined at the captain’s table, along with the admiral and the colonel of the regiment of foot which was to guard him. He soon abandoned his efforts to ‘assume improper consequence’ by, for instance, trying to embarrass the British officers into removing their hats when he did, or into leaving the dinner table when he rose. After dinner he would play chess with members of his own entourage, and whist or vingt-et-un with the British officers, from whom he took English lessons and whom he willingly entertained with accounts of the more sensational episodes of his life, particularly his Egyptian and Russian campaigns, often going into lengthy explanations and self-justifications. He was sometimes listless and absent, and occasionally indisposed through seasickness or the other discomforts of shipboard life, but on the whole he was cheerful and gave the impression of having left behind not only his ambitions, but all concern for the future of the continent he had held in thrall for so long. On the evening of 11 September, five weeks into the voyage and less than three months since he had stood at the head of a formidable army on the field of Waterloo, he read aloud for over two hours to the assembled company from a book of Persian tales.3

That same evening, the man who had contributed most to his downfall, Tsar Alexander of Russia, was giving thanks to the Lord at the end of what he professed had been the most beautiful day of his life. On a plain beside the small town of Vertus in the Champagne region of France, he had staged an extravagant display of military might and religious commitment, meant to herald the dawning of a new era of universal peace and harmony. It had commenced the day before, with a parade of over 150,000 of his troops and 520 pieces of artillery which went through their paces ‘with all the precision of a machine’, according to the Duke of Wellington. This was followed by a gargantuan dinner prepared by the famous chef Carême, lent to the tsar for the occasion by the gourmet prince de Talleyrand. The three hundred guests, who included the Emperor of Austria and the King of Prussia, as well as a glittering array of diplomats, generals and ministers, sat down at trestle tables under a marquee in the garden of a local physician, Dr Poisson, in whose house Alexander had set up his quarters. As the locality had been ravaged by war, the food for the banquet and the victuals for the troops had to be carted in from Paris.4

On 11 September, the feast of the patron saint of Russia St Alexander Nevsky and the tsar’s nameday, the troops reassembled and formed squares around seven altars erected on the same plain overnight on the pattern of a Greek Orthodox cross. Alexander rode up to the central one, dismounted and bowed his head. At this, the priests officiating at all seven altars began a Mass conducted in unison lasting more than three hours. Alexander went from altar to altar, led by the sentimental novelist turned religious mystic Baroness Julie von Krüdener, theatrically clad in a long black robe. He was entirely absorbed in the service, and ‘his attitude bore the appearance of a real devotedness and the humility of an earnest Christian’, according to an English lady present.5

Alexander saw the parade and the service as an event of cosmological significance, marking not only victory over the devils conjured by the Revolution and Napoleon, but also the death of the old world and the birth of a new one. He had been on a long spiritual odyssey, and had reached a point at which he recognised the absolute primacy of God. The parade on the plain of Vertus was a demonstration of both his own physical might and its submission to the Divine Will. He mentally associated himself and the two other monarchs who had vanquished Napoleon, the Emperor Francis I of Austria and King Frederick William III of Prussia, with the three wise kings of the Epiphany recognising the sovereignty of Christ. He wanted to give substance to this by engaging them, and all rulers, to confront the evils of the day with a new kind of government, one based on a legitimacy derived from the Word of God. Leaving aside the mechanics of this for later elaboration, he proposed that they all sign an undertaking to govern in a new spirit, a Holy Covenant (‘Sainte Alliance’ has traditionally been rendered in English as ‘Holy Alliance’, but the French word actually refers to the scriptural Holy Covenant) binding them to acknowledge the kingdom of God on earth.6

The original draft, couched in apocalyptic language, envisaged a fusion of Europe into a Christian federation, effectively ‘one nation’ with ‘one army’. This was amended at the insistence of Francis and Frederick William, but the final version nevertheless proclaimed that the sovereigns had ‘acquired the conviction that it is necessary to base the direction of policy adopted by the Powers in their mutual relations on the sublime truths taught by the eternal religion of God the redeemer’. They professed their ‘unshakable determination to take as the rule of their conduct, both in the administration of their respective States as in their political relations with all other governments, only the precepts of that holy faith, the precepts of justice, charity and peace, which, far from being applicable only to private life, should on the contrary have a direct influence on the decisions of princes and guide all their actions’.7

The Emperor Francis was sceptical; Frederick William thought it ridiculous; the British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh and the Duke of Wellington had difficulty in controlling their mirth when the tsar showed it to them. They were all nevertheless prepared to humour what they saw as a harmless whim, ‘a high-sounding nothing’ in the words of the Austrian foreign minister Prince Metternich. The document was not a public act, and they hoped it would remain buried in the archives of their chancelleries, fearing that publication would make them appear ridiculous. It was duly signed on 26 September, the eve of the anniversary of his coronation, by Alexander, Francis and Frederick William. With time, on the tsar’s insistence, it would be signed by every monarch in Europe except King George III of England (on constitutional grounds) and the pope (on doctrinal ones). What none of them fully appreciated was how much importance the tsar attached to it.8

Alexander was the only European ruler of his time to have received an education worth speaking of. It was an unusual education, ill suited to his predestined role as autocrat of a huge empire, and it added to the contradictions inherent in his position and set him apart from his brother monarchs. His grandmother, the Empress Catherine II, had taken great care in selecting tutors and meant to direct his educational programme herself, but Alexander’s French-language teacher, the Swiss philosopher Frédéric César de La Harpe, soon took over. La Harpe inculcated his own view of the world in the young prince, refuting the notion of Divine Right and teaching him that all men were equal.9

Catherine had hoped to cut her son and Alexander’s father, Paul, out of the succession, and therefore insisted that the boy spend most of his time at her court rather than with his parents. Not only his education but his personal inclination made him detest this corrupt and immoral, typically eighteenth-century court, and he valued all the more the brief moments he could spend with his mother and father, whose establishment at the palace of Gatchina was homely and, given that they were, respectively, wholly and three-quarters German by blood, comfortingly gemütlich. While his grandmother primed him for the exercise of power, he dreamed of leading a quiet life as a private citizen somewhere in Germany.

Catherine had been afraid that Alexander would be chased by women and might turn into a libertine, so she insisted that he be brought up in total ignorance of ‘the mysteries of love’. His entourage was sworn to prudery, and when out on a walk one day the teenage Alexander encountered two dogs coupling, the tutor accompanying him explained that they were fighting. Yet he was married off at an early age, to a German princess, and although he fell in love with his child bride, he found it difficult to consummate the marriage. His subsequent love life was dogged by feelings of guilt, and he would come to see the early deaths of all his children as God’s punishment.10