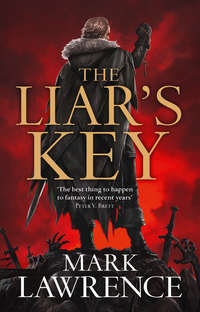

Полная версия

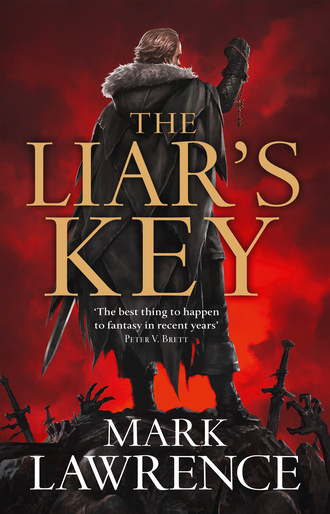

The Liar’s Key

Climbing to the Beerentoppen crater with Edris in the lead proved every bit as horrific as running before him. Staggering up ever-steeper rock-faces, hands and knees raw, feet blistered and bruised, panting hard enough to vomit a lung, I actually wished I could be back in the Sea-Troll bobbing about on the ocean.

Hours passed. Noon passed. We got high enough to see across the snow-laden peaks north and south, the going becoming even more vertical and more treacherous, and still no Snorri. It astonished me that without knowing he was pursued Snorri had kept ahead of us. Especially with Tuttugu. The man was not made for climbing mountains. Rolling down them he’d be good at.

Afternoon crawled into evening and I crawled after Edris, driven on by the threat of Alrik’s hatchet and by well-placed kicks from Knui. The peak of the mountain looked to be broken off, ending in a serrated rim. The slopes took on a peculiar folded character, as if the rock had congealed like molten fat running from a roasting pig. We got to within a few hundred yards of the top when Edris’s scouts returned to report. They yabbered in the old tongue while I lay sprawled, willing some hints of life back into limp legs.

‘No sign of Snorri.’ Edris loomed over me. ‘Not out here, not in the crater.’

‘He must be somewhere.’ I half-wondered if Snorri had lied, if he’d gone off on some different quest. Maybe the next cove held a fishing town, a tavern, warm beds…

‘He’s found the witch’s cave, and that’s bad news for all of us. Especially you.’

I sat up at that. Fear of imminent death always helps a man find new reserves of energy. ‘No! Look—’ I forced my voice to come out less shrill and panicky. Weakness invites trouble. ‘No. I wanted Snorri to give Skilfar the key – but he didn’t agree. Chances are he’ll still have it when he comes out. He’s a hard man to argue with. And then you can trade.’

‘When a man starts changing his story it’s difficult to give credence to anything he says.’ Edris eyed me speculatively, a look that had probably been the last thing half a dozen men ever saw. Even so, the blind terror that had held me since sighting their longboat had started to ebb. There’s an odd thing about being among men who are casually considering your murder. On my ventures with Snorri I’d been plunged into one horror after another, and run screaming from as many of them as I could. The terror that a dead man inspires, trailing his guts as he lurches after you, or that cold chill the hot breath of a forest fire can bring, these are reactions to wholly alien situations – the stuff of nightmare. With men though, the regular everyday sort, it’s different. And after a winter in the Three Axes I’d come to see even the most hirsute axe-clutching reavers as fairly common fellows with the same aches, pains, gripes and ambitions as every other man, albeit in the context of summers spent raiding enemy shores. With men who bear you no particular ill will and for whom your murder will be more of a chore than anything else, entailing both the effort of the act and of the subsequent cleaning of a weapon, the business of dying starts to seem a bit everyday too. You almost get swept up in the madness of the thing. Especially if you’re so exhausted that death seems like a good excuse for a rest. I returned his stare and said no more.

‘All right.’ Edris ended the long period of decision and turned away. ‘We’ll wait.’

The Red Vikings distributed themselves across the slopes to seek the entrance to Skilfar’s lair. Edris, Alrik, and Knui stayed with me.

‘Tie his hands.’ Edris settled down against a rock. He drew his sword from its scabbard and took a whetstone to its edge.

Alrik bound my hands behind me with a strip of hide. None of them had brought packs, they’d just given chase. They had no food other than what they’d stolen from me, and no shelter. From our elevation we could see along the mountainous coast for several miles in each direction, and out across the sea. The beach and their longboat lay hidden by the volcano’s shoulder.

‘Is she here?’ The necromancer plagued my thoughts, images of dead men rising kept returning to me, unbidden.

Edris let a long moment pass before a slow turn of the head brought his gaze my way. He gave me an uneasy smile. ‘She’s out there.’ A wave of his hand. ‘Let’s hope she stays there.’ He held his sword toward me. ‘She gave me this.’ The thing put an ache in my chest and made me shiver, as if I remembered it from some dark dream. Script ran along its length, not the Norse runes but a more flowing hand reminiscent of the markings the Silent Sister used to destroy her enemies. ‘Kill a babe in the womb with this piece of steel and the poor wee thing is given to Hell. Just waits there for its chance to return unborn. The mother’s death, the death of any close relative, opens a hole into the drylands, just for that lost child, and if you’re quick, if you’re powerful, all that potential can be born into the world of men in a new and terrible form.’ He spoke in a conversational tone, his measure of regret sounding genuine enough – but at the same time a cold certainty wrapped me. This was the blade that had slain Snorri’s son in his wife’s belly, Edris the man who started the foul work that the necromancers continued and that ended with Snorri facing his unborn child in the vault at the Black Fort’s heart. ‘You watch the slopes, young prince. The necromancer’s out there, and that one you really don’t want to meet.’

Alrik and Knui exchanged glances but said nothing. Knui took off his helm, setting it on his knees, and rubbed his bald scalp, scraping his nails through sweat-soaked straggles of red-blonde hair to either side. In places the helm had left him raw, bouncing back and forth on the long climb. The day had taken its toll on all of us and despite the awfulness of my predicament my head started to nod. With the horror of Edris’s words rattling about in my brain I knew I wouldn’t ever sleep again, but I lay back to rest my body. I closed my eyes, sealing away the bleakness of the sky. A moment later oblivion took me.

‘Jalan.’ A dark and seductive voice. ‘Jalan Kendeth.’ Aslaug insinuated herself into my dream, which up until that point had been a dull repetition of the day, climbing the Beerentoppen all over again, endless images of rocks and grit passing under foot, hands reaching for holds, boots scrabbling. I stopped dead on the dream-slopes and straightened to find her standing in my path, draped in shadow, bloody with the dying sun. ‘What a drab place.’ She looked about herself, tongue wetting her upper lip as she considered our surroundings. ‘It can’t really be this bad? Why don’t you wake up so I can see for real.’

I opened a bleary eye and found myself staring out at the setting sun, the sky aflame beneath louring clouds. Alrik sat close by sharpening his hatchet with a whetstone. Knui stood a little way off where the slope dropped away, watching the sun go down, or pissing, or both. Edris seemed to have disappeared, probably to check on his men.

Aslaug stood behind Alrik, looking down on the dark mass of his hair and broad shoulders as he tended his weapon. ‘Well this won’t do at all, Jalan.’ She leaned to peer behind me at my hands, wedged between my back and the rock. ‘Tied up! And you, a prince!’

I couldn’t very well answer her without drawing unwanted attention, but I watched, filled with the dark excitement her visits always provoked. It wasn’t that she made me brave exactly, but seeing the world when she stood in it just took the edge off everything and made life seem simpler. I tested the bonds on my wrists. Still strong. She made life simple … but not that simple.

Aslaug set one bare foot on the helmet Alrik had set beside him, and laid her finger against the side of his head. ‘If you launched yourself at him and struck the top of your forehead against this spot … he would not get up again.’

I gestured with my eyes toward Knui, just ten yards down the slope.

‘That one,’ she said. ‘Is standing next to a fifteen foot drop … How quickly do you think you could reach him?’

Under normal circumstances I’d still be arguing about the head butt. I would have guessed as zero the likelihood that I could pick myself up, cover the distance to Knui without falling on my face. To then knock Knui off the cliff while not following him over was surely impossible. I also wouldn’t have the nerve to try it, not even to save my life. But with Aslaug looking on, an ivory goddess smoking with dark desire, a faint mocking smile on perfect lips, the odds didn’t seem to matter any more. I knew then how Snorri must have felt when he battled with her beside him. I knew an echo of the reckless spirit that had filled him when the night trailed black from the blade of his axe.

Still I hesitated, looking up at Aslaug, slim, taut, wreathed in shadows that moved against the wind.

‘Live before you die, Jalan.’ And those eyes, whose colour I could never name, filled me with unholy joy.

I tilted away from the boulder that supported me, rocked onto my toes, and started to fall forward before straightening my legs with a sudden thrust. Suppressing the urge to roar I threw myself like a spear, forehead aimed for the spot on Alrik’s temple where Aslaug had laid her finger.

The impact ran through me, filling my vision with blinding pain. It hurt more than I had thought it would – a lot more. For a heartbeat or two the world went away. I recovered to find myself lying across Alrik’s unresisting form, head on his chest. I rolled clear, trying to see out of eyes screwed tight against the pain. Down the slope Knui had turned from the cliff edge and his contemplation of the sea.

Getting on your feet on a steep incline with your hands bound behind you is not easy. In fact I didn’t quite manage it. I lurched, half-stood, unbalanced, and set off down the mountainside flat out, desperately trying to get each foot in front of me in time to keep from diving face first into the rock.

Knui moved quickly. I aimed at him as the only chance for stopping my headlong dash. He’d already advanced a couple of yards and was unslinging his axe when, totally out of control, I cannoned into him. Even braced against the impact, Knui had no chance. Wiry and tougher than leather he might be, but I was the bigger man and carrying more momentum than anyone on a mountainside would ever want. Bones crunched, I carried him backward, we held for a broken second teetering on the cliff edge, and with a single cry we both went over.

Hitting Alrik had been harder and more painful than I wanted or expected. Hitting Knui proved much worse. Both were gentle taps compared to hitting the ground. For the second time in under a minute I passed out.

I came to lying face down on something soft. And damp. And … smelly. I couldn’t see much or move my arms.

‘Get up, Jalan.’ For a moment I couldn’t understand who was speaking. ‘Up!’

Aslaug! I couldn’t get up – so I rolled. The softness proved to be Knui. Also the dampness and the smell. His face registered surprise, the expression frozen in. The back of his head had … spread, the rocks crimson with it. I struggled to my knees, hurting myself on the stones. Aslaug stood beside me, against the cliff, her head and shoulders rising above the edge where Knui had stood. Shadow coiled up about her, vine-like, her features darkening.

‘Y – You said the drop was fifteen foot!’ I spat blood.

‘I was next to you, Jalan. How could I see?’ An infuriating smile on her lips. ‘It got you moving though. And any fall on a mountain can kill a man, with a little luck.’

‘You! Well … I.’ I couldn’t find the right words, the fear had started to catch up with me.

‘Better get your hands free…’ She pressed back against the stone, crouching now, indistinct as the horizon ate the sun and gloom swelled from every hollow.

‘I…’ But Aslaug had gone and I was speaking to the rocks.

Knui’s axe lay a little further down the slope. I shuffled toward it and with considerable difficulty positioned myself so I could start to saw at the hide strip around my wrists, watching all the while for other Hardassa men or Edris himself to come running into view.

Even a sharp axe takes a god-awful long time to cut through tough hide. Sitting there by Knui’s corpse it felt like forever. Every few seconds I let my gaze slip from lookout duty to check he hadn’t moved. I had a poor record with killing men on mountainsides. They tended to get up again and prove more trouble dead than alive.

At last the hide parted and I rubbed my wrists. Looking up, Aslaug’s second lie became apparent. She had said if I head butted Alrik where she pointed that he wouldn’t be getting up again. Yet there he was, standing at the top of the four-foot ‘cliff’ that Knui and I sat at the bottom of. He didn’t seem pleased. More importantly, he had his hatchet in one hand and a wide-bladed knife with a serrated back in the other.

‘Edris will want me alive!’ I considered running but didn’t want to bet against how well Alrik could throw that hatchet. Also he could probably catch me. I thought about the axe lying on the rocks behind me. But I’d never swung one. Not even for splitting logs.

The Viking’s glance flitted to Knui, lying there with the rocks painted a dark scarlet all around him. ‘Fuck Edris.’

Two words told me all I needed to know. Alrik was going to murder me. He tensed, readying himself to jump down. And an axe hit him in the side of his head. The blade sheared through his left eye, across the bridge of his nose, and stopped midway along the eyebrow on the other side. Alrik fell to the ground and Snorri stepped into view. He put one large foot on the side of Alrik’s face and levered his axe free with an awful cracking sound that made me retch.

‘How’s the Sea-Troll?’ Snorri asked.

‘I’m fine! Thank you very much.’ I remained seated and patted myself down. ‘No, not fine. Bruised and damn near murdered!’ Seeing Snorri suddenly made it all seem much more real and the horror of it all settled on me. ‘Edris Dean was going to gut me with a knife and—’

‘Edris?’ Snorri interrupted. ‘So he’s behind this?’ He rolled Alrik’s corpse off the drop with his foot.

Tuttugu came into view, glancing nervously over his shoulder. ‘The southerner? I thought it might just be the Hardassa…’ He caught sight of me. ‘Jal! How’s the boat.’

‘What is it with northmen and their damn boats? A prince of Red March nearly died on this—’

‘Can you carry us away from the Red Vikings?’ Snorri asked.

‘Well no, but—’

‘How’s the damn boat then?’

I took the point. ‘It’s fine … but it’s about a spear’s length from the longboat that these two came in.’ I nodded to the corpses at my outstretched feet. ‘And there are over a dozen more with it, and two dozen on the mountain.’

‘Good that Snorri found you then!’ Tuttugu rubbed his sides like he always did when upset. ‘We were hoping they’d come ashore somewhere else…’

‘How—’ I stood up, thinking to ask how it was that Snorri did find me. Then I saw her. A little further back from the edge from where Snorri and Tuttugu looked down on me. A Norse woman, fair hair divided into a score of tight braids, each set with an iron rune tablet, a style I’d seen among older women in Trond, though none ever sported more than a handful of such runes.

Snorri saw my surprise and gestured at the woman. ‘Kara ver Huran, Jal.’ And at me. ‘Jal, Kara.’ She spared me a brief nod. I guessed her to be about halfway between me and Snorri in age, tall, her figure hidden beneath a long black cape of tooled leather. I wouldn’t call her pretty … too weak a word. Striking. Bold-featured.

I bowed as she drew closer. ‘Prince Jalan Kendeth of Red March at your ser—’

‘My boat is in the next cove. Come, I’ll lead you there.’ She pinned me with remarkably blue eyes as if taking an uncomfortably accurate measure of me, then turned to go. Snorri and Tuttugu made to follow.

‘Wait!’ I stumbled about, trying to gather my wits. ‘Snorri!’

‘What?’ Glancing back over his shoulder.

‘The necromancer. She’s here too!’

Snorri turned back after Kara, shaking his head. ‘Better hurry then!’

I set both hands to the top of the ‘cliff’ and prepared to heft myself up onto the slope above when I saw my sword hilt jutting over Alrik’s shoulder. He lay on his side, not far from Knui. Above the nose his head was little more than skull fragments, hair and brain. I hesitated. I’d killed my first man with that sword, albeit mostly by accident – at least he was the first one I remembered. I’d notched that sword battling against the odds in the Black Fort, wedged it hilt-deep in a Fenris wolf. If I’d ever done anything that might truly count as manly, honourable or brave it was done holding that blade.

I took a step toward Alrik. Another. The fingers of his right hand twitched. And I ran like hell.

9

Deep gullies, rain-carved through ancient lava flows, brought us down to the cove where Kara’s boat lay at anchor.

‘It’s a long way out,’ I said, peering through the gloom. The footing in the gullies would have been dangerous in full day. Coming down in deep shadow had been practically begging for a broken ankle. And now with the night thick about us Kara expected me to swim toward a distant and slightly darker clot of sea that was allegedly a boat. I could see the gentle phosphorescence of the waves as the foam surged over the jagged rocks where the beach should be, and beyond them … nothing else. ‘A very long way out!’

Snorri laughed as if I’d made a joke and started to strap his weapons onto the little raft Kara had towed ashore when she arrived. I hugged myself, shivering. The rain had returned. I had expected snow – the night felt cold enough for it. And somewhere out there the necromancer hunted us … or had already found us and now watched from the rocks. Out there, Knui and Alrik would be stumbling along our trail, oozing, broken, filled with that dreadful hunger that invades men when they return from death.

While the others prepared themselves I watched the sea with my usual silent loathing. The moon broke from behind a cloudbank, lighting the ocean swell with glimmers and making white bands of the breaking waves.

Tuttugu appeared to share some of my reservations but at least like a walrus he had his bulk to keep him warm and to add buoyancy. My swimming might accurately be described as drowning sideways.

‘I’m not good in the water.’

‘You’re not good on land,’ Snorri retorted.

‘We’ll come in closer.’ Kara glanced my way. ‘I can bring her closer now the tide’s in.’

So one by one, with their bulkier clothing on the raft in tight-folded bundles, the three of them waded into the surf and struck out for the boat. Tuttugu went last and at least acknowledged how icy the sea was with some most un-Viking like squeals and gasps.

I stood on the beach alone with the sound of the waves, the wind, and the rain. Freezing water trickled down my neck, my hair hung in my eyes, and the bits of me that weren’t numb with cold variously hurt, ached, throbbed, and stung. Moonlight painted the rocky slopes behind the shingle in black and silver, rendering a confused mosaic into which my fears could construct the slow advance of undead horrors. Perhaps the necromancer watched from those dark hollows even now, or Edris urged the Hardassa toward me with silent gestures… Clouds swallowed the moon, leaving me blind.

Eventually, after far longer than I felt it reasonable for them to take, I heard Snorri calling. The moonlight returned, reaching through a wind-torn hole in the clouds, and the boat resolved from the darkness, picked out in silver. Kara’s looked to be a more seaworthy craft than Snorri’s rowing boat, longer, with more elegant lines and a deeper hull. Snorri ceased his labour at the oars still fifty yards clear of the shore and the hidden rocks further in. The tall mast and furled sails wagged to and fro as waves rolled beneath, gathering themselves to break upon the beach.

‘Jal! Get out here!’ Snorri’s boom across the water.

I stood, unwilling, watching the breakers smash, collapse into foam, and retreat, clawing at the shingle. Further out the sea’s surface danced with rain.

‘Jal!’

In the end one fear pushed out another. I found myself more afraid of what might be descending from the mountain beneath the cover of darkness than of what might lurk beneath the waves. I threw myself into the surf, shouting oaths at the shocking coldness of it, and tried to drown in the direction of the boat.

My swim consisted of a long and horrific repetition. First of being plunged beneath icy water, then thrashing to the surface, gasping a blind breath and finally a few seconds of beating at the brine before the next wave swamped me. It ended abruptly when a hooked pole snagged my cloak and Snorri hauled me into the boat like a piece of lost cargo.

For the next several hours I lay sodden and almost too exhausted to complain. I thought the cold would be the death of me, but hadn’t any solution to the problem or the energy to act on it if an idea had occurred. The others tried to wrap me in some stinking furs the woman had stashed away onboard but I cursed them and wouldn’t cooperate.

Dawn found us adrift beneath clear skies a mile or two off the coast. Kara unfurled the sail and set a course south.

‘Hang your clothes on the line, Jal, and get under these.’ Snorri thrust the furs at me again. Bearskins by the look of them. He pointed to his own rags flapping on one of the ropes that secured the sail. A woollen robe I’d not seen before strained to cover his chest.

‘I’m fine.’ But my voice emerged as a croak and the cold wouldn’t leave me despite the sunshine. A few minutes later I snatched up the furs with poor grace and stripped, shivering violently. I struggled to keep from toppling arse up between the benches, face in the bilge water, and I kept my back to Kara since a man is never flattered by a cold wind – not that she seemed interested in any case.

Wrapped in something that used to wrap a bear, I huddled down out of the wind close to Snorri and tried not to let my teeth chatter. Most parts of me ached and the bits that didn’t ache were really painful. ‘So what happened?’ I needed something to take my mind off my fever. ‘And who is Kara?’ Did he still have that damn key was what I really wanted to know.

Snorri looked out over the sea, the wind whipping a black mane behind him. I supposed he looked well enough in that rough-hewn barbarian sort of way but it always astonished me that a woman would look twice at him when young Prince Jal was on offer.

‘I think I’m hallucinating,’ I said, somewhat more loudly. ‘I’m sure I asked a question.’

Snorri half-startled and shook his head. ‘Sorry, Jal. Just thinking.’ He slid down closer to me, sheltering. ‘I’ll tell you the story.’

Tuttugu came forward to listen, as if he hadn’t seen the tale unfold before him the previous day. He sat tented in sailcloth while his clothes flapped on the mast. Only Kara stayed back, hand on the tiller, gaze to the fore, occasionally glancing up at the stained expanse of the sail, pregnant with the wind.

‘So,’ began Snorri, and just as so often before on our travels he wrapped that voice around us and drew us into his memories.

Snorri had stood in the prow, watching the coast draw near.

‘We’ll beach her? Yes?’ Tuttugu paused by the anchor, a crude iron hook.

Snorri nodded. ‘See if you can wake Jal.’ Snorri mimed a slap. He knew Tuttugu would be more gentle. The fat man’s presence cheered him in ways he couldn’t explain. With Tuttugu around Snorri could almost imagine these were the old days again, back when life had been more simple. Better. In truth when the pair of them, Jalan and Tuttugu, had turned up on the quay in Trond Snorri’s heart had risen. For all his resolve he had no love of being alone. He knew Jal had been pushed into the boat by circumstance rather than jumping of his own accord, but Tuttugu had no reason to be there other than loyalty. Of the three of them only Tuttugu had started to make a life in Trond, finding work, new friends, a woman to share his days. And yet he’d given that up in a moment because an old friend needed him.