Полная версия

The Night Mark

Three strikes was an out, but four balls was a walk.

Faye walked.

It was easier to do than she’d thought it would be. Hagen hadn’t put up a real fight. Knowing him, he’d probably been secretly relieved. The past four years she’d slowly lost touch with the world until everything had started to take on the feel of a TV show, a soap opera that played in the background. Occasionally, she’d watch, but never got too invested. Finally, she’d simply switched off the television. The Faye and Hagen Show was over. No big loss. The show only had two viewers and neither of them liked the stars.

A couple months on the coast would do her good. The saltwater cure, right? Wasn’t that what the writer Isak Dinesen had said? “The cure for anything is salt water—sweat, tears, or the sea.” Faye should get more than enough of all three photographing the Sea Islands in the middle of summer.

As soon as she’d packed her bags and drove away from Hagen’s house for the final time, Faye hit the road. In summer tourist-season traffic, the drive from Columbia to Beaufort took nearly four hours. Who were all these people lined up in car after car heading to the coast? What did they want? What did they think they’d find there? Faye wanted to work, that was all. She wanted to do well with this assignment since one good job led to another and then another. Life stretched out before her from now until her death, her work like the centerline of the highway and if she kept her eye on that line maybe, just maybe, she might not careen off the edge of the road.

Faye took the exit to Beaufort, the heart of what was known as Lowcountry in South Carolina. It felt like its own country as the terrain turned flatter and greener and swampier the deeper she drove into. After the exit, she passed a huge hand-painted sign off to her right. Lowcountry Is God’s Country, it read in big black letters. Interesting. If she were God she’d pick the Isle of Skye in Scotland maybe. Kenya. Venice. But Lowcountry? Seemed an odd choice. She wondered what being “God’s country” entailed, and then she passed four different churches, four different denominations, and all in a quarter-mile stretch. Clearly God owned a whole lot of real estate around here.

Faye made it to Beaufort by dinnertime. Needing to conserve her money, Faye had rented a room in Beaufort. Just one room in someone else’s home. She wouldn’t have a private bathroom, a situation Hagen would have found an unacceptable affront to his dignity, but Faye found she didn’t mind, not at all. Now that she didn’t have to think of anyone’s needs but her own, she’d discovered just how little she needed.

The house was on Church Street, a faded Southern Gothic Revival river cottage, a revival someone had forgotten to revive. White paint in need of power washing, three tiers of verandas missing a baluster or five, Spanish moss and ivy competing for ownership of the trees... Faye liked it immediately. It was owned by Miss Lizzie, a woman who rented the rooms out mostly to college kids attending the University of South Carolina’s Beaufort campus. So few students attended classes in the summer, however, that Faye had ended up with what Miss Lizzie said was the best room in the house.

Faye’s hopes were not high, but Miss Lizzie, an older black woman with a spray of pure white hair around her head like an icon’s nimbus, welcomed her into the house with a wide smile that seemed genuine. Faye did her best to match it. The third-floor room she’d been given surpassed Faye’s low expectations by a large margin.

“Here you go,” Miss Lizzie said. “I keep this as my guest room. No kids up here. I’d hate to put a grown woman like you in the same hall as my college boys. They get a little rowdy. You’ll like it up here if you don’t mind the stairs. My sister stays here when she visits but she’s not coming round again until October. Too hot for her.”

“It’s beautiful,” Faye said, wearing a smile she didn’t have to fake. She hadn’t been impressed by anything in a long time, but this room spoke to her in its spareness. The floors were hardwood, a deep cherry stain polished to a high shine so that in the evening sunlight she could see every last rut and groove on the floor, elegant as an artist’s brushstrokes. The wounds gave it character and beauty. The bed was a four-poster, narrow, like something she’d seen in preserved historic homes. It bore an ivory canopy on top and ivory bed curtains; an ivory bedspread with a double-wedding-ring Amish quilt in a shade of dark and light blue was folded at the bottom. In case she got cold, Miss Lizzie said. South Carolina in June and July? Faye was fairly certain she wouldn’t have to worry about catching a chill.

“Closet over there,” Miss Lizzie said, pointing at a buttercream-yellow door. “Dresser there. These doors lead to the balcony,” she said, indicating a set of French doors. “No screen doors, so try not to let the mosquitoes in.”

“Are you Catholic?” Faye asked.

“Of course not. I go to Grace Chapel. It’s AME.” The tone of denial Miss Lizzie employed made it sound as if Faye had asked her if she were a government spy hiding out on foreign soil. Then again, that was what many people once thought of Catholics in the United States.

“I saw the prie-dieu.” Faye pointed at the carved wooden kneeler by the bed. A ceramic gray tabby cat sat on top of it next to a lamp. “That’s why I ask.”

“The what? I thought that was some kind of step stool or side table.”

“It’s for praying. Private prayer. You kneel on this bottom step here and maybe rest your prayer book on the top part.”

“You’re of the Catholic faith?” Miss Lizzie asked, touching her chest as if to clutch at nonexistent pearls.

“No, but I’m a photographer. I did a photo shoot of Catholic churches for a book once.”

“I see. You here to photograph things?”

“For a calendar. A fund-raiser.”

“Well, that’s nice, then. Who doesn’t need funds these days?”

Faye laughed. “Anyway, it’s very pretty.” Faye touched the prie-dieu. It was simply carved but sturdy stained rosewood. The wood was lighter where the knee would go on the bottom board as if someone had prayed on it many times. Were his prayers answered? Why did Faye assume it was a he?

“It’s from the lighthouse, the old one,” Miss Lizzie said.

“Lighthouse? The one on Hunting Island?”

She shook her head. “Not that one. North of Hunting Island, there’s another island. Bride Island.”

“Bride Island? That wasn’t in my guidebook.”

“Only locals call it that. And it wouldn’t be in the guidebook. It’s private. Rich black lady owns it,” Miss Lizzie said with quiet pride. “Paris Shelby.”

“Any idea if Ms. Shelby allows visitors on the island?”

It sounded promising, an old lighthouse on a private island. Maybe it hadn’t already been photographed to death. Perfect subject for a preservation society calendar.

“I wouldn’t know. And Mrs. Shelby hasn’t been around much this summer.”

“Thank you anyway. Maybe I can find a way out there.”

“Here’s your key,” Miss Lizzie said, handing her a silver key on a brass ring. “Now, you remember this isn’t a hotel. I won’t be changing your sheets or bringing you breakfast. That’s your job.”

“I don’t need much of anything, I promise.”

“You can use the kitchen. We let the kids use it as long as they clean it up, so you can use it, too. The top shelf in the fridge is yours. I cleaned it off.”

“I appreciate it. I’m only here to work this summer. I’ll stay out of your hair.”

“My hair thanks you kindly,” Miss Lizzie said with a debutante’s coy smile. “There’s not much left of it to get into anyway.” She patted the wispy curls back into place and left Faye alone in her new home.

Faye set her suitcase on the luggage rack and her equipment case on the bed. A fine room. Perfect for her needs. She’d live the simple life this summer—no television, no movies, no surround-sound speakers and five remote controls only Hagen knew how to work. She’d sleep and she’d eat and she’d work, and when she wasn’t working she would walk or read or do nothing at all.

She lay on the bed, staring up at the canopy and planning her itinerary for tomorrow. A drive around the islands to scout locations and maybe a few pictures if the light was right. No time to waste. She was no one’s wife anymore. If she didn’t work, she didn’t eat. She should have been afraid, but she wasn’t. Supposedly she’d lost “everything” in the divorce and had been left with almost nothing. Turned out almost nothing was exactly what she wanted.

With help from a sleeping pill, Faye slept well that first night in her new room. In the early dawn hours, when the sun had just begun to peek into the room, she woke up and felt the strangest sensation, a sensation she hadn’t felt in more than four years.

Hope.

Hope for what, she didn’t know, but she knew it was hope because it got her out of bed before six o’clock. She knew there was something out there she wanted and something told her if she chased it, she just might catch it. She put on her bathrobe and opened the French doors, but froze when she saw the visitor perched on the wooden railing of the little balcony.

She wasn’t sure what it was—a heron or a crane or an egret—but it was a big damn bird, that was for certain. Two feet tall, white body, blue-black head and a long bill, sharp as a knife. Faye considered retreating but stayed riveted in place, staring.

“Have we met before?” she asked the bird. Its only reply was to turn its head rapidly toward the sun. She wasn’t sure if that was a yes or a no.

“Wait a second... I remember you.”

Faye recalled a cold morning on the Newport pier, a morning she would never forget, though she might want to. She’d gone at sunrise, early so no one would see her and try to stop her. On that winter morning, she’d found herself the sole visitor on that lonely pier, a sorrowful sight in her gray trench coat and Will’s ashes so terribly heavy in her hands. As she walked to the end she was tempted to keep walking. What was that old insult? Take a long walk off a short pier? Yes, that was exactly what she’d wanted to do. But then a large white bird with a black head had landed on a boat tie-up, startling her with its size and sudden appearance. They’d eyed each other for a few seconds before Faye had continued walking toward the end of the pier. She’d fully expected the bird to take off as she neared it, but it hadn’t. It stayed while she knelt on weathered gray wood and poured the ashes into the water and it stayed when she stood up again. It flew off only as she started to walk toward land. For a second—a foolish stupid second—she’d thought the bird was watching over her, making sure she didn’t take that long walk off that short pier.

“What are you?” Faye asked the bird, not expecting an answer. The bird merely shook its wings in reply, and Faye sensed it readying to take off.

“Hold on. Stay there one second, big bird. I want to get my camera. Just a camera. Don’t be scared.” Faye backed into the room, trying her hardest not to make the floor squeak under her feet. From her leather camera bag, she pulled out her Nikon. Carefully, she crept to the doors, but the moment she lifted the camera to her eye, the bird launched itself off the balcony. The one shot she captured was a blur of white in the distance. Faye laughed. Well, there was a very good reason she hadn’t gone into nature photography.

After an early breakfast of cereal and tea, she found Miss Lizzie weeding her garden out back. Faye sidestepped a discard pile of murdered plants. Discerning what was weed and what was garden took better vision than Faye’s twenty-twenty, and she wasn’t sure Miss Lizzie could tell the difference, either. Faye asked her if she knew anyone with a boat. Miss Lizzie suggested she talk to Ty Lewis in Room 2 on the first floor. He was a marine biology student doing some project on the islands over the summer. He went out on a boat often, Miss Lizzie said. Even if he couldn’t take her out he could probably point her in the direction of someone who could.

When she returned to the kitchen she found her man. Had to be him. He wore a T-shirt—a shark and octopus locked in battle on the front with the words The Struggle is Real underneath. He had dark brown skin inked with dozens of black tattoos up and down both arms—fish, it looked like, lots and lots of fish—and half a dozen silver piercings: eyebrow, both ears, nose and lip, plus a bonus upper-ear piercing. He had dreadlocks pulled back in a ponytail. He was also handsome enough Faye had to remind herself she was thirty, not twenty.

Twice she reminded herself of that fact.

“Are you Ty?” she asked, pulling a mason jar—Miss Lizzie’s version of iced tea glasses—from the cabinet.

“I am if you’re asking.” He gave her an appraising look and the appraisal came in high.

“I’m asking,” she said. “Faye Barlow. And don’t flirt with an old lady. Our hearts can’t take that much excitement.”

“If you’re old, I’m Drake. What can I do for you?”

“I heard you have a boat? Or access to a boat?”

“I might have access to a boat,” he said between bites of scrambled eggs and sausage. He sat on the counter, not at the table. When was the last time she’d sat on a kitchen counter? High school?

“Would you let me pay you to take me out somewhere on your boat? I need to take some pictures of a lighthouse.”

“You can drive to the lighthouse. Best beach in the state. Don’t tell anybody that, though. I wanna keep the tourists at Myrtle Beach, where they belong.”

“Miss Lizzie said there’s another lighthouse, one on some place called Bride Island. Do you know it?”

“I know it. Hard to get near it, though. There’s a sandbar in the way.”

“Guess that’s why they needed a lighthouse. Can you get into the area at all? I have a long-range lens on my camera.”

“I can probably do that.”

“Today? Tomorrow?”

“This evening? Five?” He hopped off the counter and poured himself a massive glass of orange juice, so big it made her teeth hurt and her blood sugar spike just looking at it. Did college kids know that their days of eating and drinking like that were numbered? She wanted to tell him, then decided to spare him the awful truth that time was a thief, and a metabolism like his would be the first thing it stole.

“What’s the charge?”

“Dinner. With me. You know, after we get back from the boat.”

“You’re too young for me, and I’ve been divorced for about—” she pretended to check her watch “—ten days.”

“You celebrate the divorce yet?”

“Is that a thing people do? Celebrate the painful dissolution of a marriage?”

“Who wanted the divorce?”

“I did.”

“You love him?”

“No.”

“Like him?”

“No, but he didn’t like me, either.”

“You have kids?”

“No.”

“Good in bed?”

“Fair to middling,” Faye said, shrugging.

Ty laughed. “Then hell, yeah, it’s a thing to celebrate.”

“I will have an age-appropriate celebration. You’re too young for me.”

He looked at her, tight-lipped and disapproving. “I’m twenty-two.”

“I’m thirty.”

“Thirty? Oh, my God, Becky, where were you when JFK was shot?” he asked in a Valley girl voice.

She glared at him.

“You flirt weird. Did you learn this in one of those men’s magazines with a woman in a metallic bikini on the cover?”

“Possibly. Is it working?”

Faye sighed. “It’s working. But just dinner. I’m not sleeping with you. I’m supposed to be sad.”

“Are you sad?” he asked, stepping up to her and looking her right in the eyes. She couldn’t remember if Hagen had looked her in the eyes the entire last year of their marriage. She’d forgotten how scary it was to be seen.

“Yes,” she said.

“Because of the divorce.”

“No, not that.”

“Then why?”

Faye smiled. “Who knows?” A rhetorical question. She knew why she was sad, but Ty didn’t need to know.

“We’ll go to the ocean today,” he said. “It knows things. Maybe it can help you.”

Okay.

So.

Faye had a date with a twenty-two-year-old college student. That was unexpected. Probably a very bad idea, as well. Maybe a terrible idea. Then again, he did have a boat. And he was cute. And she was single again.

And... For a split second while flirting with Ty, Faye had been almost okay. The saltwater cure seemed to be working already. And for a woman who’d been in mourning for four straight years, Faye knew “almost okay” was as good as it was probably ever going to get.

But she would take it.

3

Ty had the boat, but Faye had the car. Unless she wanted to ride twenty miles on the back of Ty’s scooter, she would be driving herself on her own date. It was nice. She felt very modern. Old but modern.

Ten minutes into the drive to the dock on Saint Helena Island, Faye pulled over in a church parking lot and gave Ty the keys.

“You want me to drive?” he asked, cocking his pierced eyebrow at her.

“I can’t drive and location scout at the same time without getting us in a wreck. I assume you can drive?”

“I have my learner’s permit,” he said, taking the keys.

“You’re cute.”

“The goddamn cutest,” he said as he opened the door and got behind the wheel.

As Ty drove, Faye stared out the window and jotted the occasional note on her steno pad. She should take pics of the old Penn School. The trees surrounding it were some of the most photogenic she’d ever seen. She also noted a crumbling ruin of a church that would make for a beautiful shot, maybe even the cover of the calendar. Thankfully Ty didn’t pester her with small talk as he drove them to the boat. He pointed out interesting scenery here and there—that road took her down to the old fort, this road took her to a converted plantation house... Useful things. Helpful things. She made notes of them all.

They arrived at the dock, and Faye nodded her approval at the boat. It looked adequately seaworthy, some kind of speedy fishing boat converted into a research vessel. It had a blue-and-white hull with the words CCU Marine Science painted on the bow and the number four on the stern.

“You won’t get in trouble for taking me out on your school’s boat, will you?” she asked.

“It’s mine for the summer. As long as I give it back in one piece with a full tank of gas, and I get my work done, they don’t care what I do with it.”

“What are you working on this summer?” Faye asked as Ty took her hand to steady her on the wobbling boat ramp. Inside the boat she sat on the battered white vinyl seat, mindful of the box of instruments on the floor as Ty settled in behind the wheel.

“Beach pollution mostly,” he said, as he steered the boat away from the dock. “The effects of pollution on coastal wildlife, the fish especially. I’m taking water samples all summer up and down the coast.”

“Are these beaches polluted?” she asked. “They look clean to me.”

“Think about rain,” Ty said. “Think about a rainstorm in your town. Water comes down and washes everything clean, right? What sort of stuff gets washed away in a rainstorm?”

“Bird shit,” she said.

“Squirrel shit.”

“Bat shit,” she said, and they both laughed.

“Oil from your car on the street. All that gets washed into the gutter, which goes into the sewer. Where does that sewer go?”

“Please don’t tell me the ocean.”

“Goes right to the ocean. Decades ago they built these drainage pipes from the cities, and those pipes empty into the ocean near the beaches. That’s why you shouldn’t swim around here after a rainstorm. Like swimming in a sewer.”

“That’s disgusting.”

“It is what it is,” he said with a shrug. “People want to pretend all that shit magically disappears into the gutter and is never seen again. But it’s gotta go somewhere, right?” He started the engine and eased the boat toward open water, steering it neatly between two sailboats, one with the elegant name Silver Girl and the other with the less-than-elegant name The Wet Dream.

The boat bounced hard as it skimmed over the top of a large wake left by a fifty-foot yacht. But Ty seemed imperturbable at the helm. He drove with a focused calm, intent without intensity—a true expert. She liked experts. The world needed more people who were good at their jobs.

“So why marine biology?” Faye asked, shouting over the steady hum of the engine.

“Grew up near Myrtle Beach, watched sea turtles hatching when I was a kid and fell in love. That’s all I’m trying to do—keep these beaches for the turtles. Don’t give a shit about the people.”

“That’s not very nice.”

“People are why we’re in this mess. Last year I pulled ten plastic bags, two Coke cans, half a nylon fishnet, and a goddamn pink Croc shoe, size six, out of the stomach of a shark. You know what we say about that down here?”

“What do we say about that down here?”

“That ain’t right. That’s what you say. You try it.”

Faye put on her thickest faux Southern accent. “That ain’t right.”

“Not bad. I took pics of all that mess, made signs and hung them up on every beach from here to Savannah.”

“You must make lots of friends that way.”

Ty snorted a laugh. “Yeah, they aren’t too happy with us when we tell everybody their fun summer vacations are killing the wildlife. They think we’re scaring off tourists. We are, but we’re not doing it to be assholes. We’re doing it to wake people up.”

“Are you waking them up?”

“All we can do is ring the alarm. Most people aren’t going to start paying attention until they have dirty ocean water on their doorstep. Bad as it is, I admit I’m gonna laugh when those rich white boys are playing golf in three feet of seawater.”

“My ex-husband was one of those rich white boys. He loved coming down here to golf with his buddies.”

“Sorry,” he said, looking awkward.

“I’m not.” She winked at him.

Ty smiled and hit the gas. Coming here had been a good idea. She should thank Richard for sending her the job. This job was just what she needed—work. Real work. Meaningful work. Plus sand, surf, seafood and a chance to be her old self again. She knew the old Faye, the Faye who’d existed before the miscarriages and the failed marriage... The old Faye wasn’t sad like the new Faye. The old Faye felt things, felt them deeply. The old Faye fought for things, too, didn’t give up or give in. And the old Faye would definitely go on a date with Ty. Absolutely.

Ty glanced at her out of the corner of his eye. A college boy had just checked her out.

Maybe the old Faye and the new Faye had something in common.

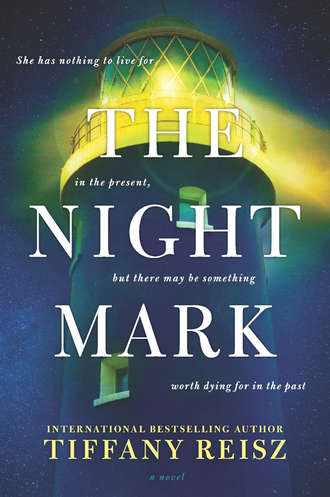

“Is that it?” Faye asked, pointing to the top of a lighthouse peeking out from the tree canopy.

“That’s Hunting Island. Pretty lighthouse. You can climb it for two dollars.”

“I think I can cover that. I’ll go tomorrow. Today I want to see Bride Island’s lighthouse.”

“We’re a couple miles out from there still. The lighthouse is on the north beach. You can see it a lot better than the Hunting Island lighthouse. It was never moved so it’s right on the water.”

“What do you mean it was never moved?” Faye asked, pausing to dig a strand of hair out of her mouth. She’d forgotten how windy it got on a boat.

“You see that long spit of sand there?” Ty pointed to what looked like a yellow cat’s tail lounging a few hundred yards out into the water.

“I see it.”

“That used to be land. And that’s where the Hunting Island lighthouse stood. Built in the 1870s, but they had to move just a few years later. The land had eroded that much already. Going, gone, almost gone...”

“It’s really all going away, isn’t it? The coast?”

“Let’s just say you won’t catch me buying a beach house.”

“It’s too bad. I always feel like a better person when I’m on the water.” The air smelled cleaner here. The water seemed purer. She wanted to strip off her clothes and dive off the side of the boat and let the water baptize her a free woman.