Полная версия

A Psychological Perspective Of The Health Personnel In Times Of Pandemic

A Psychological Perspective

of

Health Personnel

in

Times of Pandemic

Juan Moisés de la Serna

Translated by Lauren Izquierdo

Tektime Editorial

2020

“A Psychological Perspective of the Health Personnel in Times of Pandemic”

Written by Juan Moisés de la Serna

Translated by Lauren Izquierdo

1st edition: May 2020

© Juan Moisés de la Serna, 2020

© Tektime Editions, 2020

All rights reserved

Distributed by Tektime

The total or partial reproduction of this book, nor its incorporation into a computer system, nor its transmission in any form or by any means, be it electronic, mechanical, by photocopy, by recording or other means, is not allowed, without prior permission and in writing from the editor. The infringement of the aforementioned rights may constitute a crime against intellectual property (Art. 270 and following of the Penal Code).

Contact CEDRO (Spanish Center for Reprographic Rights) if you need to photocopy or scan any fragment of this work. You can contact CEDRO through the web www.conlicencia.com or by phone at: 91-702-19-70 /93 272 04 47.

Prologue

Afterward the successful reception of the book entitled “Psychological Aspects in Times of Pandemic” where a number of issues from the perspective of psychological science are addressed, related to the impact of the appearance of COVID-19 on the lives of citizens, and afore readers´ insistent request for a text focused on health personnel, from there came this book.

The purpose of this, it is to offer updated information on the psychological aspects of who have been described as the battlefront against the advance of COVID-19 from a perspective of scientific psychology, for which reference will be made to the latest publications in this regard.

A rigorous and up-to-date vision of the contributions of the science of psychology told in a way that is accessible to everyone, with the aim of helping to understand the emotional impact of this situation on health personnel, as well as the present and future consequences of the same.

Homage

Although it may be obvious, to speak of the health personnel is to speak of those who are in charge of health, whether physical or mental, and depending on how the distinction between professions and specialties within the health field is established in each country.

Perhaps the most notable difference in a hospital may be between health personnel versus non-health personnel, in this first case being the doctors, nurses and assistants; while within the category of non-health, management and administration personnel would be included, as well as support personnel such as orderlies, guards and even cleaning personnel, all of them essential for a more or less large health center to function conveniently.

The previous distinction is not trivial but has been brought up, because although the text focuses on health personnel in times of pandemic, it should not be forgotten that they can carry out their work thanks to the entire human team that is supporting them and collaborating with them; sometimes being “invisible” for patients and relatives, but as indicated before, they are of essential importance

Illustration 1 Tweet Thanking Personnel

Dedicated to my parents

Prologue

Chapter I. Contextualizing

Healthcare in Europe

About COVID-19

The name of COVID-19

The evolution of the pandemic

Changes in the healthcare system

Chapter 2. Reaction to COVID-19

Social phenomena

Chapter 3. Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Personnel

Depression in Healthcare Personnel

Anxiety in Healthcare Personnel

Sleeping Problems in Healthcare Personnel

Resilience in Healthcare Personnel

List of Illustrations

References

Conclusions

Chapter I. Contextualizing

Before going deeper about the psychological and emotional impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Personnel, this work must be contextualized within the framework of a pandemic that affects globally and without precedent in modern history. It has been putting in check to each one of the health systems as it has affected the population.

Despite seeing its consequences in China, where it began, sometimes, until the first cases were counted in each territory, the governments did not begin to take measures in this regard.

A chronology that has barely started a few months ago and that has been affecting more and more countries. The first cases were imported, by citizens from affected areas, who have unknowingly spread the virus around the world.

A situation in which each government have taken different measures, but in all cases, the fight for the eradication of the virus has been in charge of Health Personnel yet at risk of their own lives in the caring of patients who came requiring health care, many times, with urgency.

Healthcare in Europe

Health Personnel can be differentiated according to the category given to them in each country. For example, between medical and nursing personnel, professionals who perform complementary functions, but whose percentage of the population vary depending on the European country which is being talked about.

Thus, and in the specific case of Spain, this is above the European average in terms of the number of medical professionals working in healthcare, this average is 3.6 per 1,000 inhabitants in 2019; while in the case of nurses, Spain is below the average, whose percentage in 2019 at the European level was 8.5 per 1,000 inhabitants.

Greece, Austria and Portugal are the countries with a higher ratio of doctors in the European Union, and those with a lower ratio, Poland, Romania and England.

Regarding the nursing community, among the countries with a higher ratio per 1,000 inhabitants are Norway, Iceland and Finland, while those with the lowest ratios in the European Union are Greece, Bulgaria and Lithuania.

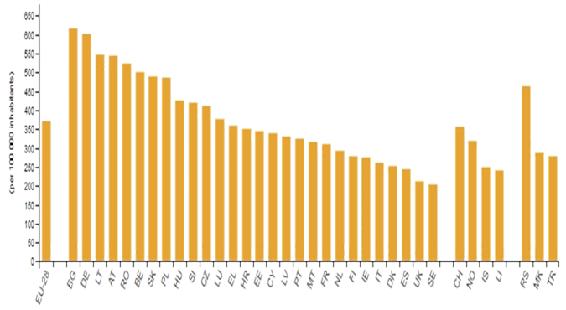

Illustration 2 Health Personnel in Europe

It is necessary to clarify, in order to offer a vision closer to reality, that in the specific case of Spain, where there is a lower ratio than the European average of nurses, that this is not due to a lack of personnel, but because there are not counted the nursing assistants, despite the fact that in other European countries they are equated in functions with nurses.

It is also reported that in the case of Greece and Portugal, the number of doctors who are licensed to practice is counted, and not so those who work in health centres, hence their percentage is above the European average.

With this first approach, it is wanted to offer a general overview of the Health Personnel that each country had, and specifically Spain, all of this prior to the appearance of COVID-19, an aspect that is relevant in terms of the human resources that are going to be fighting the advance of this disease, a panorama that, as will be explained, has changed rapidly in terms of availability and the need for new professionals.

This reflects the enormous differences between countries of the European Union, which in first place could be counting for a greater or lesser workload that the said personnel will have to bear, thus, the more doctors and nurses per 100,000 inhabitants, the easier the attention to population will be, since it will be more human resources, at least that is what could be thought before learning about some events that have changed the reality of these personnel in weeks.

But before proceeding, it is necessary to comment that there are also other indicators to take into account to know the “strength” of the health system of each country, so we can look at the number of hospital beds available, thus with data from 2014 the average of the European Union, there are 372 beds per 100,000 inhabitants, Spain being below the average with 242 beds (Eurostat, 2020) (see Illustration 3).

The countries with the highest number of available beds between 2014 and 2015 were Bulgaria, Germany and Lithuania (with 616, 601 and 557 beds per 100,000 inhabitants respectively); while those with fewer beds were Sweden, England and Spain (with 203, 211 and 242 beds per 100,000 inhabitants respectively)

Therefore, and based on the previous data, it can be said that the countries of the European Union that have more personnel and material resources to face better a health crisis would be Greece, Austria and Portugal in number of doctors; Norway, Iceland and Finland in number of nurses; and Bulgaria, Germany and Lithuania in number of hospital beds.

And on the contrary, those who are “worst” prepared to face a health crisis would be Poland, Romania and England in number of doctors; Greece, Bulgaria and Lithuania in number of nurses; and Sweden, England and Spain in number of beds available.

In the specific case of Spain, with respect to the average of the European Union, there would be more doctors than the average and fewer nurses, taking into account the caveat indicating that auxiliary personnel who also perform their role in Health Centres are not included in this account (OECD / European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2019).

Regarding the criterion of available beds per 100,000 inhabitants, as of 2015, Spain was below the average in particular with 43% fewer beds available per 100,000 inhabitants (O.M.S., 2020a).

Although the foregoing does not allow us to establish distinctions in terms of efficiency criteria, quality of the caring offered, ease of access or the users satisfaction with the hospital service in each country and specifically in Spain, it does offer an overview of the strength or weakness depending on the material and human resources available prior to the onset of the global health crisis.

Regarding the quality of the caring, it must be taken into account that when a person is hospitalized, either for an upcoming operation or to recover from a trauma or intervention, in these cases patients usually spends days and even weeks in the hospital. In this “short” period of time, you will receive a “visit” from Healthcare Personnel, which includes the doctor who monitors the patient’s progress.

While it is true that the caring can be good in the hospital, sometimes patients and relatives may complain about the “coldness” of its personnel, since they fulfil their function, but sometimes interacting as little as possible with the patient or the patient´s family members.

A situation that has been seen as unnecessary and in some cases even detrimental for the proper functioning of the hospital, where aspects of the patient’s physical recovery are usually prioritized over emotional ones.

Despite this, some Health Centres work closely with clinical psychologists, who train Health Personnel to properly relate and communicate with patients.

Most of all, when “bad news” have to be given, where especially careful is needed in saying it, and it is necessary to know how to deal with the reactions from patients, which can range from a rapid decline in mood, to an outbreak of anger.

But while it is true that knowing how to communicate is important, it is not enough for a quality doctor-patient relationship, so what should be done to improve patient caring?

This is what has been tried to answer with a study carried out by the Nursing Care Research Center, the School of Nursing and Midwifery, together with the Firoozgar Hospital of the University of Medical Sciences of Iran; the Rajaie Center for Research and Cardiovascular Medicine of the University of Medical Sciences of Iran; and Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Iran) (Khaleghparast et al., 2016).

The study was a qualitative one, in which 51 hospital users were interviewed, including patients, relatives and Health Personnel.

The subject of the semi-structured interview was about the centre’s medical visit policies, paying special attention to the comparison between restrictive and open policies.

The former, restrictive patient care policies are governed by a pre-established visit schedule for healthcare personnel, where both the time of the visit is set, as well as the duration of the visit.

In the latter, in open patient care policies, there is no visiting schedule or restriction on the time spent with the patient.

The answers of the three groups, patients, relatives and Health Personnel were categorized in order to analyse it. Thus, on restrictive policies, the results show the advantages that avoid chaos; guarantees medical visits even to patients who do not want visits; controls infections; offers regularity and stability to the personnel; and in disadvantages; lack of emotional “connection”; lack of information about the patient’s condition; and a limited professional visit time.

With respect to open policies, the results indicate the advantages of reducing stress and increasing patient safety; helps the family with the patient’s primary care; provides education to patients and families; a better environment is created in the doctor-patient relationship; and in disadvantages the violation of the privacy of the patient and interference with the treatment

As the authors point out, new research is required before any conclusions can be drawn in this regard, mainly due to the small number of study participants and the qualitative methodology used. Despite this, it should be noted that restrictive policies guarantee the doctor’s visit once a day; something that is perceived as insufficient for both patients and families. Likewise, the Healthcare Personnel feels more comfortable with open policies, since without losing professionalism they can offer more personalized and quality patient caring.

Despite the advantages of one system or the other, it must be taken into account that the application of these results to a health center will depend a lot on its size, thus open policies seem more suitable for a health center of size medium or small; where staff can have “quality time” with their patients, without the need to adhere to a strict schedule, while in larger centres, where the number of patients per doctor is high, the best system would be that of restrictive policies, where a minimum of care is guaranteed to all patients.

Despite this, the demand from both patients and their families that Healthcare Personnel should not lose the “warmth” of human relationships during their visits, whether restrictive or open, has to be highlighted.

That is to say, and regaining the idea of this section, what has been presented is the data regarding the human resources of Health Personnel, doctors and nurses, as well as the material resources considered these as the number of beds available, not attending to other characteristics in terms of quality of the caring or how modern the technological equipment is.

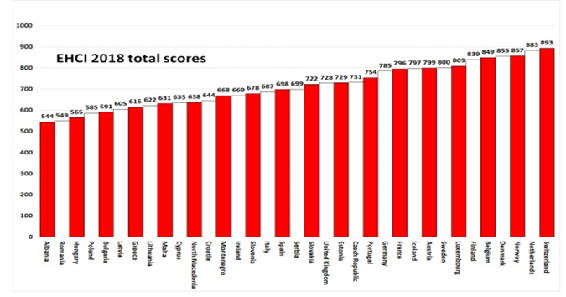

To know these aspects, Health Consumer Powerhouse Ltd must be consulted which publishes the Euro Health Consumer Index annually, where 46 indicators are taken into account, including areas such as the patient´s rights or the information received, establishing from this a ranking of health systems in Europe, with Switzerland, the Netherlands and Norway having the best scores in 2018; and the worst Albania, Romania and Hungary (Health Consumer Powerhouse Ltd, 2018) (see Figure

Illustration 4 European Health System Ranking

Even with all the data presented, it is not possible to establish a priori which country will better withstand a health crisis, since in these circumstances the available resources in terms of personnel and number of beds may have a greater relevance, compared with the results regarding satisfaction with the rights of the patient or information that he receives.

In addition, and alongside with the above, it must be taken into account that governments are implementing a series of measures that make the number of patients attended wherever they reach health services staggered or not, so that a “controlled” progress of a disease can be adequately cared of, by a health system with “adjusted” resources, while a “peak” of contagion and therefore of patients requiring hospitalization can cause the collapse of any health system, no matter how prepared it is.

About COVID-19

Although it is a new virus, a lot is already known about COVID-19, starting with the family it belongs and the characteristics of this Coronavirus (@CSIC, 2020) (see Illustration 5)

Information has been discovered thanks to the involvement of numerous research laboratories and universities around the world, and having in addition for the first time the genetic sequence of the virus released by China as a way to stimulate the search for a cure.

These two factors have allowed that different tests are currently being carried out throughout the world, trying to know how to combat its advance and especially to reduce the death rate.

From the O.M.S. answers are offered about what COVID-19 is, what its symptoms are, how it spreads, or what is the recovery and death rate among those infected, and others (O.M.S., 2020b).

But despite this, various aspects are still being investigated today for which there is still no answer, especially in relation to an effective treatment, both preventive and to reduce the consequences of the

Illustration 5. Tweet Image of COVID.19

The name of COVID-19

One of the problems of social psychologists is to achieve customer loyalty to a brand, this being the one we use to identify a certain person, product or company.

Normally when we think of a company like Coca-Cola, McDonald or Ikea, we usually do it with respect to the products they sell. If we look at other brands such as U.P.S., Iberia or Microsoft, we do it on the services they offer.

Something that will decisively influence the acquisition of the product or service in question, not only based on our own criteria, but also on the influence of the opinion of others and the media through advertising.

Likewise, when we think of Stephen Hawking, Barack Obama or Rafael Nadal, we no longer do so in products or services, if not because of their Personal Branding or personal brand that they have developed thanks to their scientific, political or sports careers respectively, that is, emotional aspects are associated with the brand, which can be linked to a person, company and even location.

Well, the same happens when “misfortunes” are to be called, as happens when designating tropical cyclones that annually hit a large part of the Caribbean and North America.

As reported by the World Meteorological Organization (World Meteorological Organization, 2020), these names follow pre-established lists that rotate, leaving in many the memory of the effects of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 or Ike in 2008.

Therefore, in principle, these names are not related to the date on which it occurs, the violence or the areas most affected, among these there are English or Spanish (for example, Barry or Gonzalo respectively), male or female (for example , Lorenzo or Laura respectively), but does the name of tropical cyclones have an impact on the population?

This is what has been trying to find with an investigation carried out by the Department of Administration and Companies; in conjunction with the Department of Psychology, the Communications Research Institute, and the Women and Gender Surveys Research Laboratory of the University of Illinois; together with the Department of Statistics of the Arizona State University (USA) (Jung, Shavitt, Viswanathan, & Hilbe, 2014).

The study analysed the climatic consequences of hurricanes in the United States during the last six decades, differentiating them based on masculine and feminine names, first finding that those with feminine names had been the ones that had led to the greatest destructive effects and deaths.

It must be remembered that the list of names is predetermined and that their assignment is consecutive, so a priori there is no relationship between the gender of the name and its violence, so the most surprising thing about the study is that they passed a list of names of hurricanes, 5 male and 5 female to 346 participants, so that they assessed through a Likert-type scale from 1 to 7 to what extent each of the hurricanes on the list was considered violent.

The results show that hurricanes with male names tended to be valued as more destructive than those with female names, regardless of the gender of the participants.

Which allowed us to understand why sometimes when faced with notices from the authorities, more or less attention is usually paid to prevention, for example, simply because the assigned name is male or female.

On the other hand, the name of diseases in the health field is usually indicated by acronyms that are related to some identifying characteristic of the site, symptoms or consequences.

Thus, and within the family of coronaviruses, there have been several outbreaks before, such as in the case of SARS-CoV that emerged in China in 2002, whose initials correspond to the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus and which refers to its symptoms; the MERS-CoV that arose in Saudi Arabia in 2012 and whose initials in English refer to the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, where the symptoms and location are described; and the COVID-19 that emerged in 2019 in China whose initials in English refer to the Coronavirus Disease of 2019, without making any indication of the symptoms or the town where it arose.

It should be taken in mind that the term COVID-19 has not been the first to be used for this disease but rather it has been a change introduced almost two months after the first case reported to the WHO emerged, which has led to some proposing that the motivations for modifying it by incorporating an “official” name could have been carried out to avoid the negative economic consequences of associating a type of disease with a region or population (@radioyskl, 2020) (see Illustration 6).

In this way, the aim would be to eliminate the names of “China virus” or “Wuhan virus”, terms that point directly to the source of the infection.

A deference to China that some health professionals denounce, for not having the same consideration with other populations as in the case of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus.

Despite the fact that an official name of COVID-19 has been given, the population has continued to use the denomination of Viruses and especially Coronavirus to learn about the symptoms, prevention measures or extension of the disease, and although it is still too early to understand the reason