Полная версия

Hell in the Heartland

HELL IN THE HEARTLAND

Jax Miller

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

First published in the US in 2020 by Berkley, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

Copyright © Jax Miller 2020

Cover design by Ellie Game © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Cover photograph © Drunaa / Trevillion Images

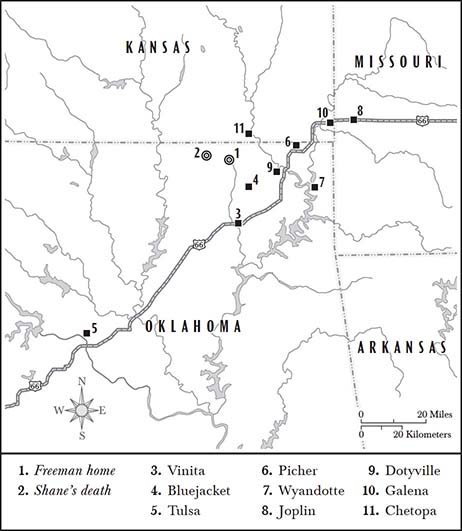

Map by David Lindroth

Jax Miller asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008335182

Ebook Edition © July 2020 ISBN: 9780008335205

Version: 2020-07-03

Dedication

My writing is forever dedicated to my children, LA, K, AI, & S.

This book is dedicated to Lauria and Ashley, forever young.

Map

Disclaimer

While this book contains dramatizations and some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals, this is a true story.

Epigraph

I was born on the prairie and the milk of its wheat, the red of its clover, the eyes of its women, gave me a song and a slogan.

—Carl Sandburg’s “Prairie” (1918)

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Disclaimer

Epigraph

Prologue

SECTION 1: THE FIRE

1. Mother, Kathy Freeman

2. Daughter, Ashley Freeman

3. Father, Danny Freeman

4. Best Friend, Lauria Bible

5. One Body

6. One Woman, Lorene Bible

7. The Scene of the Crime

8. The Prime Suspect

9. Day Two and the BBI

SECTION 2: CORRUPTION

10. The Initial Theories

11. Son, Shane Freeman

12. The Alleged Cover-up of Shane Freeman

13. Boyfriend, Jeremy Hurst, and Pop Pop, Glen Freeman

14. The Last Letter of Kathy Freeman

15. The Murder of DeAnna Dorsey

SECTION 3: DRUGS

16. The Most Toxic Place in America

17. The Outlaw Lands

18. The Outlaw Lands (Continued)

19. East of Welch

20. The Ballad of John Paul Chapman

21. The Confessions

SECTION 4: LATER LEADS

22. The Edges of Oklahoma

23. Another Avenue

24. Chetopa

25. The Searches of Chetopa

26. Revival

27. “This Place Is Ate Up.”

SECTION 5: THE ARRESTS

28. The Arrest

29. Ronnie Dean “Buzz” Busick

30. The Insurance-Verification Card

31. David “Penny” Pennington

32. Like Lightning

33. No End

Picture Section

Page on how to help

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Jax Miller

About the Publisher

The sheriff once told me this part of Oklahoma was haunted, that once you’re a part of it, you can’t ever leave. Here I am, walking along the edge of the Freemans’ forty-acre property in the middle of the night and hoping not to be shot. I’m up against my own crippling anxiety and a backdrop of stars where in the winter of 1999 sat a small trailer that you’d never find by accident. In the pitch-black, from a dark and desolate dirt road I look up the hill, imagining how the home would have looked in flames, where inside were thought to be parents Danny and Kathy Freeman, their teenage daughter, Ashley, and Ashley’s best friend, Lauria Bible.

God help them all.

Twenty years later, the Freemans and the Bibles remain without answer about what really happened that December night, strangled in the prickly weeds of rumor, rumors that include drugs, police corruption, serial killers, and the Second Coming of Jesus Christ himself. The secrets are out there in the Oklahoma prairie’s whisper, her taunts. And as imaginary shadows move around me, I learn that while the prairie is playful by day, she plays tricks at night. Somewhere out there, closure might be found after all this time. If I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a million times: the prairie has her way.

But the stranger-than-fiction story of the Freeman-Bible case has hardly blipped on the radar of true crime, and it’s hardly made its way out of Oklahoma and the intersection where Missouri, Kansas, and Arkansas almost meet to make crosshairs crookedly aimed at the gut of America. The fervors of youth are fading from those who stand today with questions, and those suspected to know where Ashley Freeman and Lauria Bible are now are taking the answers to their graves. Time is running out for an untold story, and I wonder who will be left to tell it when those closest to it are no longer here.

The taste of the prairie wind brings me back to being high, and a panic attack begins to spark in my chest. If I don’t work this story, I’ll have to sit with the unimaginable fear that found me only once I began this case. It is a hereditary monster that took the lives of the women before me in my family, including my mother, who will die from the effects of drugs in the midst of my investigation. Escapism. Fixation. While I get my demons from my mother, I take the diligence of my on-the-spectrum father and spend the next four years with the ghosts of Oklahoma.

Standing at the edge of the Freeman property, I go over (and over and over) what happened in the hours leading up to the fire and silently ask the girls where they went. But they don’t answer, and instead, the hills whisper around me like they can smell my fear.

Like I said: the prairie has her way.

1

MOTHER, KATHY FREEMAN

December 29, 1999

The Day Before the Fire

Summer is when I come to Oklahoma to meet the living, but I reserve winters for trying to acquaint myself with the dead; in the season when those I came to write about last lived, when it’s still. I sometimes hear them better in the silence than from the survivors who still talk about them today. I may never get inside their minds the way I wish I could, or the way they get into mine. But I can at least feel the snow on my skin atop this hill where the trailer once sat, and wrap my fingers around the shoulder of an ax and wonder if our knuckles ache the same. In the lockjaw of winter, when memories of braiding watermelon vines and of blackberry-stained feet are long forgotten, Oklahomans carry on as they always have. They’re hunters and gatherers by nature, canning and pickling, with freezers full of dove and deer, not just prepared but fortified for winter. They are, by default, a people who can withstand most anything.

Amidst the buzz-cut fields and dead-grass whistle, the white-tailed deer stand on their hind legs and pluck for persimmons’ sweet orange flesh from the trees, which helps hunters track their paths. The folklorists tell me that cutting into the fruit at autumn’s first frost is a way to predict the winter ahead. In 1999, the kernels were shaped as knives, foretelling of blade-twist winds (the spoon-shaped seeds mean heavy snow, while the fork-shaped formations forecast only dustings).

In 1999, blade-twist winds it was.

Kathy Freeman, age thirty-seven, paused momentarily to watch her breath hit the cold air hard. She was smoking more and more, to the point where the December air offended her lungs and the stains on her teeth were growing more prominent. The bleakness of winter brought with it a palette of homestead tans and doeskin browns, something lacking color, lacking life. Then a chop and a crack echoed down the hill when Kathy split another piece of wood. Outside the twenty-eight-by-fifty-six-foot mobile home, the air smelled like fresh coffee, bacon, and maple, an ambience of something cozy and all-American. Young barn cats played by the splinters, coming and going as they pleased, attracted to the smell of breakfast inside. Despite the temperature being thirty degrees Fahrenheit, Kathy kept warm by the sweat of her brow, wearing only faded Levi’s and a T-shirt branded with the logo of the optometrist’s office where she used to work. With breakfast still on the stove, she had just enough time to split a few more logs before returning, leaving the ax behind.

It was her daughter’s sweet sixteen, there was much to do, and she was running behind on her homemaking chores.

She took the yard’s chill inside with her, where a woodstove cooled just to the left of the front door. The home was small but nicely kept, toeing that fine line between cluttered and comfy. Kathy dropped an armful of firewood by the stove as she walked in, wincing at a splinter that found its way into her thumb’s knuckle. She sucked on it, kicking off her worn Keds, which kept her feet cold, and dashed for the stove top, always the dutiful wife despite hating the cliché, for she also worked like a man with backbreaking endurance until her hands were nothing but two callused mitts.

The faux-wood-paneled walls were filled with display cases of Cherokee arrowheads, hundreds of points made of flint and bone, vibrant against red velvet and protected by glass, stained by the blood of the American Indians to whom this land once belonged. The open living room seemed to hang by the deer antlers that sprouted from the walls, with Ashley’s laundry neatly folded on the couch. The TV was mistakenly turned to a soap, electric blue and amber light glowing through pan grease and unfiltered-cigarette smoke. On the floor was the family Rottweiler, Sissy, more nourished than any of the Freemans. The dog hardly raised her ears toward Kathy’s moving about, half asleep for the lazy Wednesday afternoon.

Kathy added cracked black pepper and a touch of fresh milk to the fat drippings for the sawmill gravy, a Southern staple she was fixing for her husband for a late biscuits-and-gravy breakfast. Where the sausage smoke ended and Kathy’s Natural American Spirit smoke began was clear from two different shades around her head, like a dual-toned halo. Her husband, Danny, had excused himself to go outside shortly before, halfway done for the day with whatever it was he was doing, living in a perpetual state of being in between odd jobs. Welding here, selling his own handpicked wildflowers and willow branches to the florist there, whatever it took.

“My head’s at it again,” Danny often groaned, half excusing, half resentful. “Damn it anyway.” He dropped a pat of butter into his black coffee and disappeared into the afternoon, swallowed by silver sun, never feeling the need to explain to Kathy where he was going or what he was doing. Then again, she never felt the need to ask. She didn’t want to be that kind of farm wife, the kind whose floral dresses matched the wallpaper, the kind to put curlers in her hair before bedtime. God forbid. Gone were the calico-dressed women longing for their husbands out in the dust. Gone were the cowboys lit by a lantern’s flame and navigating by the stars. Broken was the American dream and the barefoot girl that she used to be, playing in the bog and twirling red clover in her teeth. And she was just fine without all them frills. Between stirring the gravy and grabbing fresh eggs from their carton, she found a good ten seconds to find a sewing needle and go after that damn splinter.

Kathy had this natural-born killer’s stare about her, one she was hardly aware of, what people refer to today as “resting bitch face.” Her hair matched the fields that gave birth to her, just as wild, always catching the breeze. But 1999 was a trying year for the woman, her shoulders a fixed inch higher since her teenage son’s death. Murder! she’d correct you if you mentioned it within earshot. Cold-blooded murder! Her eyes were but two swollen welts, the eyelashes plucked one by one out of nervous compulsion. Who could blame her?

Outside in the backyard, the blast of Danny’s shotgun at the bottom of the hill, taking her attention from the splinter and over to the door of the refrigerator, where a lined piece of paper hung, a page she’d rewritten several times over earlier in the week. At the top, under a magnet made to look like a cow, in her tall but neat cursive, the words “ONE SHOT,” a reference to the shotgun slug that had pierced her son’s side.

My name is Kathy Freeman. I live west of Welch, OK—a Craig County resident all my life …

She gave it a read, once over, with her hands on her hips and that inadvertent look of contempt nudging down the corners of her mouth.

“Ashley!” she called out over the stove top’s bubble and hiss. “Grab yer breakfast, birthday girl. It’s already after noon!” Kathy sucked hard on her cigarette, knuckles wide by chores never-ending and the pressing need to distract herself from seventeen-year-old Shane’s death. Murder, goddamn it!

2

DAUGHTER, ASHLEY FREEMAN

December 29, 1999

The Day Before the Fire

Ashley Freeman had that adolescent thickness about her, one she was just starting to grow out of as the teeth in her head straightened into their adult positions. Her hair was dirty blond and homespun but tamed in a ponytail, her skin paler from bunkering in the shelter of “ay-kern” trees while wearing camouflage jackets that reversed into safety orange. She was just at the age when you could glimpse into what she’d look like as an adult, like her mother, but young enough that you could put your finger on exactly what she had looked like as a child. She was as country as country came. Photos often showed the girl, tall at five feet seven, sporting rifles and slinging the carcasses of various animals over her shoulder, proud like mink. Family bragged of her marksmanship and ate the deer she’d drag home from the hills, supper killed with unflinching precision. Sometimes, over the woodstove, Danny would make snack trays of turkey strips and deer steaks, paired with cans of Pepsi to wash them down, of which he could drink a six-pack in a day. Later, he’d make wind spinners from the cans and hang them from the gutters, to add flutter and rustle to their singing home. As a child, Ashley would watch the hypnotic silver and blue play against the sky on idle afternoons.

Like a good Oklahoma girl, she did her best to suppress her emotions, bred to see crying as weak but anger as strong. This is the Oklahoma way. But pain seemed to gnaw its way from the inside out, and in the past year, she’d lost a few pounds of that baby chub and the gold of her hair was losing its luster. Life had slapped her hard in the face, leaving a red mark of grief on her cheek that just wouldn’t go away since her big brother’s death. That afternoon, she arranged and rearranged the handpicked flowers of a bouquet, one made of hay from the yard, holly, Christmas rose, and fiery witch hazel sprigs, ready to replace the last bouquet from the side of a rural county road that had been stolen, plucked from the gravel.

The floral arrangement took her back to times when she and her father traveled together, over and under the nearby Oklahoma state lines between there and Kansas, Missouri, and Arkansas. They went anywhere the gas could take them to collect cattails and lotus pods and various wildflowers (cattails were their best seller at ten cents apiece to local florists). Ashley’s mother would stay home to work at an optometrist’s office while Shane continued on with his extracurricular activities and time spent with friends. Notwithstanding the cattails, which would fill the backseat at any given time, Ashley and Danny would arrange their handpicked commodities into spectacular sprays of sunroots, rattlesnake masters, and Indian blankets, displays of fire and sky wrapped in ribbon and sold for twenty bucks apiece, though you could get the price down to fifteen if Ashley was feeling kind enough. That was summertime, when red sunsets lingered over the fields after long days, hair tangling in the thick, hot wind of a speeding truck. She’d trace her hand over the passing fields and a dirty fingernail along the horizon, wishing for all the things that teenage girls wished for: the carefree heart, the white-trash kiss, reckless love. What little she could have known of growing up back then, walking in her father’s shadow and eating fried pickles and pink lemonade on the side of the road to let the truck cool.

And now her sixteenth birthday.

It was the second half of winter break, one that lacked the vibrations of Christmas due to the weight of mourning. Ashley straightened the blond straw under her knee while listening to Billboard’s Best of Country from her brother’s radio. Because she had just moved up from her room to his, half of his furniture remained, though she couldn’t bear looking at his Sports Illustrated calendar a second longer. She kept his football trophies and dusted them often, his worn Nikes at the foot of her bed, the blue-and-white Welch Wildcats football jersey he should have been buried in hung on the wall. She’d even spray his favorite Tommy Hilfiger cologne once in a while on her own flannel shirts just so she could feel him near.

Ashley ignored the thick smell of breakfast, appetite lost with her youth. She thought of a million things she’d rather be doing than turning sixteen, including, but not limited to, practicing for her driver’s test.

“You know you’re ready,” her friend reassured her. “You’ve only been doing it since you were five.”

“It’s different when you’re taking a test,” Ashley replied. “You have to signal and all that crap. That’s why Jeremy’s been driving with me. Showing me all the formal stuff.”

“Sure.” The friend smiled, making quotation marks with her fingers. “‘Formal stuff.’”

Ashley threw baby’s breath at her best friend, sixteen-year-old Lauria (pronounced “Laura”) Bible, who planted the flower behind her own ear.

The best friends had spent the day before preparing for the livestock showings for the county and state fairs, as part of the FFA (Future Farmers of America) and the 4-H Club, community-leadership and agricultural clubs to which they belonged. They knew all there was to know about roughages, dehorning, cattle parasites, castration, cuts of beef. These were country kids who’d spent the morning adjusting the gaits and training the coats of Ashley’s goats, Jack and Jill. (Lauria had her own two pigs and a lamb back home.) They talked about seeding out the competition and making it all the way to the great Tulsa fair, which attracted more than a million visitors annually. Imagine, parades of antique tractors brandishing American flags, pie-eating contests with sun-warmed blueberries exploding on clean cotton, demolition derbies, carnival rides, and bull-riding rodeos. The county and state fairs were the very embodiment of American life in the heartland. But back in the bleakness of winter, they trained with their sights set on summer. Ashley and Lauria wandered around the property that morning, gathering the leaves of dogwoods and bois d’arcs for the goats to eat as the cold made their rough hands ache. While the “crick” babbled at the bottom of the backyard, a weeping willow swished against the ground like the straws of a broom at the west side of the trailer. In fact, that was what helped Ashley decide on leaving her old bedroom on the east end of the house for Shane’s on the west end: the branches that brushed against the windows and filtered dusk through strips of light like honey, a sense of security when the sun went down.

“Ashley!” her mother hollered from the kitchen. “Grab yer breakfast, birthday girl. It’s already after noon!”

Ashley rolled her eyes—the picture of teenage disdain. Sometimes she wished that she didn’t have to be the strong one within the family unit. Had it not been for Lauria’s stability and her support, she wondered if she’d have been able to survive that last year of the millennium.

I spend years sitting with Ashley’s family, friends, and neighbors, ambling her school hallways and stomping grounds, visiting classmates and teachers. I want to know what being Ashley Freeman was really like, and soon, another side of her emerges. Despite Ashley’s outwardly tough persona, there was something tender about her. Back then, the kids in school knew that her family home wasn’t the best, and the rumors as to why had long circulated, coming to a head with Shane’s death. One friend tells of a time she forgot that Ashley was supposed to ride home with her from school and left without her, only for Kathy to show up on the doorstep with a sobbing Ashley, demanding to know why her daughter had been forgotten. While she could hunt for and field-dress a deer by herself, she required validation from others. Though she could lift any grown man, she’d dance in her room when alone. She was never able to throw away her favorite Berenstain Bears books and stuffed animals, yet took no issue in cutting the heads clean off turkeys. She had her feet planted in the manure and her heart in the clouds. There were the face she let others see and the face she reserved for behind closed doors, the real heart of her spirit she’d share with those closest to her, including Lauria.

“We’re already late,” Kathy yelled.

“Gimme a minute!”

Together, the friends got ready to leave, oblivious of their whole lives before them. Ashley slipped on her boyfriend, Jeremy’s, high school ring and slipped into her sneakers, the soles dusty. Out there, the cricks and grain were stitched together with dirt roads that led off the beaten paths. That land breathed under their feet, heart pounding with hunger. In wait.

3

FATHER, DANNY FREEMAN

December 29, 1999

The Day Before the Fire

Out here you’ll find no one, and no one will find you, and that was exactly its appeal when Danny Freeman moved his family from rural Vinita to West of Welch back in 1995: father, mother, son, and daughter striving for a simpler way of living.