Полная версия

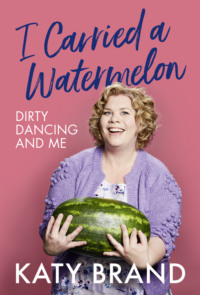

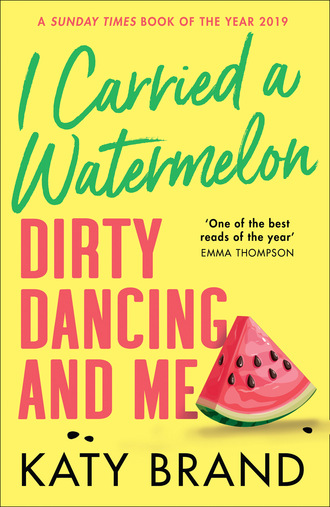

I Carried a Watermelon

Baby Houseman loses her virginity twice on screen, and the first time is through the medium of dance. The moment she wangles her way into the staff party with the infamous watermelon is where her sexual odyssey really kicks off. In the next 90 minutes or so, we discover that Dirty Dancing has an awful lot to say about sex, youth and freedom – much of which is extremely helpful to a young girl watching, with her eyes out on stalks.

Johnny Castle approaches Baby as she stands awkwardly in the corner, seeming gruff and unimpressed at first that his cousin Billy has smuggled in a ‘guest daughter’ – as we have already learnt, due to excellent exposition, proprietor Max Kellerman does not approve of extra-curricular staff-guest fraternising, at least not for the dancers, so Johnny is understandably concerned that this intruder may get them all in trouble.

Baby is already slightly turned on by the deeply filthy dance displays going on all around her. As she follows Billy through the steaming, writhing mass, her skin flushes and her lips part. She looks a bit ‘glowy’, shall we say. But that’s nothing compared with what’s in store for her sharp sexual trajectory. Because Johnny Castle casts off his initial wariness and gets the devil in him for a moment. He invites Baby to dance. And so, it begins …

Using dance as a proxy for sex isn’t new. In fact, using anything as a proxy for sex is fairly standard across all art forms – cutting to fountains gushing, or the tide rushing in at the crucial moment, is now so clichéd that it’s a joke in itself. Even Jane Austen was at it in Pride and Prejudice, when she used Elizabeth Bennet’s carefree lone muddy walks, her flushed cheeks and bright eyes shining from the fresh air, to convey a kind of vigorous drive and lust for life that does the job for Mr Darcy. But here in Dirty Dancing, the metaphorical shield is Durex-thin – it is in fact quite explicit. Basically, dancing = sex with your jeans on.

The scene continues, with Baby joining the throng at Johnny’s invitation. As the more experienced dancer, he calms Baby down, gets her to feel the rhythm, and she stiffly lurches and thrusts with all the style and grace of Theresa May at a hip hop night, and as you watch, you feel the cringe go deep on her behalf.

But he doesn’t laugh at her, or belittle her. As Otis Redding belts out ‘Love Man’, he pulls her to him, tells her to look in his eyes, to relax her shoulders, and – what do you know? – within minutes they have locked groins and she has become like a cooked noodle in his arms. The song ends, and he leaves her, but she can barely stand up. She appears to be melting from the vagina outwards. The message is this: a good dance will prepare you for good sex. You need not fear losing your virginity with a man who dances like this. It won’t even hurt, for god’s sake – you’ll be so ready for it, you’ll have excess natural lubricant to bottle and sell.

I don’t need to be the latest person to describe the awkwardness of watching sex scenes with your parents – there are a million comedy routines covering it, and we all know what that’s like in any case from sphincter-tightening first-hand experience. And so yes, on my first viewing there was all the usual ‘eyes-straight-ahead-don’t-swallow-don’t breathe’ stuff going on, which meant my enjoyment was a bit … subdued.

Part of the sex appeal is how imperfect some of them look at times, by modern film standards. It’s not all painted and pretty; it’s sweaty and lusty, with mascara running down their cheeks with the sheer heat of it all. I remember being absolutely thrilled with it – not necessarily in an explicitly erotic way, but it certainly gave me a feeling of warm excitement. It all looked so physical and immediate – you can feel the chemistry coming off the screen. Sex is natural and easy. Bodies are fun and sensual. So, feel good about yourself. And I did, after watching it.

So, while dancing is obviously the main focus of the film, and the dancers set the tone in a smoky, oily kind of way, it’s sex that really underpins the whole thing. In her review of Dirty Dancing when it first came out in 1987, the eminent American film critic Pauline Kael wrote in the New Yorker, ‘dancing is a transparent metaphor for main character Baby’s sexual initiation … this is a girl’s coming of age fantasy: through dancing she ascends to spiritual and sensual perfection.’

Ascending to spiritual and sensual perfection sounds pretty good to me now as a 40-year-old woman, never mind as a teenager, but as a young girl approaching puberty the thought of sex terrified and fascinated me in equal measure. I had a habit of trying to get boys’ attention, but as soon as they showed any interest, I would feel sick and back off hard. Of course, I was still too young to actually do it, or really want to do it, but trying out your powers early on the opposite sex, with varying degrees of success, seems to be a rite of passage for many girls.

My attempts were clumsy to say the least. I was not in any way coquettish or even especially nice, and thought being sarcastic was highly seductive. If I fancied someone a bit, I would relentlessly take the piss until there could be no doubt that I considered them scum of the earth. It was counterproductive, but kept me and my delicate feelings protected in public. ‘You’ll cut yourself on that tongue one day,’ a teacher said to me after overhearing a conversation I was having with one poor victim.

The idea of flirting, or being soft in any way, made me feel ill. I can’t explain why, but it was a physical sensation – a visceral recoil. Thankfully, I got over it, so perhaps it was just nerves, but for a long time my relationships were always verbally combative – I saw it as a sign of affection, or rather, the kind of affection I was willing to express at the time. The idea that you should be nice to boys if you want them to like you seemed perfectly logical to me, it was just when it came to anything romantic that I went a bit strange. I had lots of friends who were boys, and they had always seemed fairly interchangeable with the girls. I didn’t wear dresses much, or skirts. I liked blue jeans, blue t-shirts and scruffy trainers. I mostly had my hair short, and could barely be bothered to brush it. If I dressed up at all, it was leggings and a large jumper. Before I watched Dirty Dancing that first time, I don’t think I really understood intimacy between couples, and the kind of ‘sex appeal’ that was usually shown in films felt like it came from another planet. I couldn’t relate at all.

But now here was a girl called Baby, who wore jeans and white plimsolls, and denim shorts, and loose-fitting t-shirts, who was slightly awkward and bad-tempered with this man, Johnny, and yet he seemed to like it. Here was a girl like me, wearing clothes like mine (only better), having her first sexual relationship with a man who clearly knew his way around. She didn’t wear make-up, she didn’t have a push-up bra, she didn’t stick her bum out, or pretend to be weak in his presence. She didn’t use any tricks. She was wholly and completely herself, authentic in all respects, even as she changed her entire world view in the space of three weeks. And, as a result, she had the shag of her life. In fact, read ‘Time of My Life’ as ‘Shag of My Life’ and you get quite an accurate sense of the journey of the film – perhaps that was Eleanor Bergstein’s euphemistic intention all along.

I believe this formed the basis for how I approached the notion of sex appeal as I entered my teens for real. I knew I wasn’t pretty in the sense of ‘pretty-pretty’ – I knew who those girls were and what you were supposed to look like to be one of them, but I didn’t really try to be like them. I still don’t most of the time. I have learnt through my professional work that if you want to look properly good, or as good as you can possibly look, you need a minimum of two hours with a professional hair and make-up artist, seriously restrictive undergarments (or ‘shapewear’ as it is coyly known) and a four-inch heel or higher. I’d rather be comfortable. I’d rather look slightly shit, smile for the picture, resolve never ever to look at it, and then enjoy the rest of the evening. I even applied this to my own wedding, which is why we didn’t have a professional photographer. I don’t regret it – I had the best time. I wore a blue dress because I always manage to spill my food, I partook eagerly of the hog roast and pavlova, and then danced all night.

Penny – played by eighties pin-up Cynthia Rhodes – Johnny’s dance partner, drips old-school glamour and always looks astonishing. Tiny Jennifer Grey looks positively dumpy next to her sometimes, but it doesn’t matter. Because it doesn’t matter to Baby, and it certainly doesn’t matter to Johnny. Late in the film, Baby’s more groomed older sister Lisa offers to do her hair, but then stops herself with the line, ‘No, you’re pretty in your own way.’

‘Pretty in your own way’ became my lifeline. My mantra. There is one brief scene in Dirty Dancing where Baby tries to change herself or her appearance for Johnny, and that is when she stops on the stone steps to apply her sister’s ‘beige iridescent lipstick’, swiped from her drawer in the family cabin. And even then she makes a bit of a joke about it, draping herself over a railing in a cartoonish mockery of how a Hollywood siren might move. She’s having fun, and to be honest, that lipstick would be so plain it would barely register. The only other time she makes an effort is when she dances with Johnny at the Sheldrake, and that is for professional reasons. Yes, her outfits get sexier and skimpier as she learns to dance, but this does not appear calculated to have a sexual pull on Johnny, more for us to see that she is gaining confidence in her own body as she learns what it can do.

Other than these moments, it’s ‘pretty in your own way’ the whole time. I still look at myself in the mirror, and I see the imperfections, and then I catch myself and murmur comfortingly, ‘You’re pretty in your own way.’ This is partly to excuse the sheer lack of effort on my part on a day-to-day basis, but also it’s a kind, realistic and affirming little ritual that makes you forget the pressures of having to contour yourself until you basically resemble a Kardashian, no matter the original shape of your features.

In fact, there is never any suggestion that Baby has to achieve a certain ‘look’ to get Johnny’s attention, or win his desire. The first time they have sex, it follows the car journey back from the Sheldrake, in which Baby climbs in the back seat to change out of her more glamorous and revealing dancing outfit and back into the jeans and shirt she was wearing before. Johnny seems genuinely attracted by her character, her commitment, her goodness and her determination. That is what turns him on. However you look at it, this is a great message for a young girl entering the world of sexual politics for the first time. Or anyone, in fact.

There are no games with Baby and Johnny, and when you think about it, that is quite striking. They work together, they fancy each other, so they fuck. They communicate directly with each other. They don’t send messages through friends, or play hard to get. They want it, so they do it. And then they do it again, and again, and again. The central issue of the film is not whether she has slept with him too fast to retain his respect, or whether he fancies someone else more, or whether she’s cool enough for him. It’s whether or not she can solve the mystery of a series of purse thefts from the hotel for which he is accused before he is fired. And whether she can respect herself, even when she loses the respect of her father. It’s strong stuff. And it’s all very sexy, especially when they keep dancing with each other half-naked and a bit sweaty.

Even when they think they are going to have to separate for good, there is very little angst or stress. Watching this scene now, it is incredible to me how mature it is. Standing opposite each other next to his car on a dusty track, they embrace. He says, ‘I’ll never be sorry,’ she agrees, and then he drives away. She waves for a moment, pauses and then turns to walk back to the hotel. It’s so weirdly calm. They both seem to accept that it was fun while it lasted, they had some good times, but now it’s over, and they have to go their separate ways. There is no suggestion that Baby will throw away her future for him, or that he will pursue her, or let her down at a later date. They kiss, they hug, he drives off, and she waves. And all the while ‘She’s Like the Wind’, composed and performed by Swayze himself, plays over the top. What’s not to love? When you compare it to the hysterical, ‘my life is over’ form of comparable scenes in more recent romantic dramas, it’s revolutionary. It basically tells you that you can have a holiday romance, and then get over it and get on with your life. Think how many wasted hours we could all have saved over the years, when we’ve agreed to meet up with a holiday shag back home, and then sat opposite each other in a dreary pub, wondering, faintly embarrassed, what the hell you ever saw in each other, praying no one you know comes in.

But even though I had all this formative education thanks to Dirty Dancing, my teenage years were barren, sexually speaking. In fact, I think you could even throw the word ‘frigid’ around and I wouldn’t kick you in the nuts. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with not being ready, but I was definitely resisting even the most innocent of romantic encounters – a light touch, a gentle snog. I think now that part of the attraction of becoming a full-on, fundamentalist, evangelical Christian from the age of 13 to 19 was the fact that they didn’t believe in sex before marriage, so I always had an excuse. ‘I can’t have sex with you because of Jesus,’ is a very effective deterrent, if you didn’t already know …

I somehow knew that the reality would be a let-down, compared with Baby’s first experience, and therefore also the version I’d imagined for myself. My fear was in fact confirmed by my first snog, back at that Cornish campsite, at the age of 13. I remember his tongue thrusting in and out of my mouth with such vigour that I wondered whether he was trying to eat my dinner. Of course, he was young too – no doubt he is now a top-level snogger – but this put me off for a long time. It felt nothing like the soft kisses that Baby and Johnny share. But nevertheless, there was a dusky magic to it, and that moment just before the moment, when you know it’s going to happen and something inside takes over, is still a thrilling memory. That feeling of stepping outside to share a cigarette with someone you fancy, and realising they fancy you too, and it’s going to happen, and it’s going to happen now, is one of the most delicious sensations known to mankind.

Deep down I was waiting for Johnny Castle. An older man, perhaps. Or at least someone who knew what to do. In the film, he is meant to be 25 to Baby’s 17, and Swayze himself was 34 when it was made (Grey was 27). This keeps us just on the right side of ‘slightly pervy’, but the age gap, both real and imagined, has been remarked upon before. It is really the sincerity and innocence of the performances that keeps us from any true discomfort.

Some have said maybe Johnny does this every year, and Baby is simply his latest victim, but I’m not having that. Because there is nothing untoward or unequal about the sex Baby and Johnny have. In fact, Swayze himself understood this, saying in a TV profile of his life and career that the film shows the loss of Baby’s innocence, but the regaining of Johnny’s. A more beautiful and insightful comment on their respective journeys, I could not compose.

And when that astonishing sex scene finally happens, crucially, it is Baby who initiates it. She seduces Johnny. She comes to his cabin, expressly disobeying her father, who has literally just told her she is to have nothing more to do with him. She’s performed her duties at the Sheldrake, so there is no need for her to come at all. Baby may hope to use apologising to Johnny for her father’s behaviour as a cover for her late-night visit, but she knows perfectly well what she’s really after, and suggests they dance together, one last time. As they move to the cracked soul of ‘Cry to Me’ by Solomon Burke, she runs her hands over his naked torso and grips hold of his buttock like a woman who knows exactly what she wants. It is one of the sexiest scenes of all time. Watching them blend together, in and out of bed, is enough to give you palpitations. And the best thing about it all is that Baby clearly loves it – she is not ashamed or guilty, she just wants more. Here is a teenage girl losing her virginity with no misery, shame or tears. She loves sex. It can be done!

When you are brought up with the constant reinforcement that your virginity is both a hindrance and a prize, that the losing of it will be traumatic no matter how you do it, can you conceive of how astonishing this film is? Let’s stand back and give it a moment. Let’s applaud it. Teenage girls can love sex and not be ‘little minxes’ or ‘sluts’. Who knew? I want more of this.

I wrote a play in 2018 called 3Women, with an 18-year-old girl in it, and I wanted the same for her. Writing her dialogue, when she’s talking about how much she loves sex, was such a thrill. I thought of Baby throughout. When she shouts that immortal line to Johnny as they argue about their fate – ‘Most of all, I’m scared of leaving this room and never feeling again, my whole life, the way I feel when I’m with you’ – I think I knew, even as a young girl, that she meant sex – there’s unfinished business here, and Baby could surely sense it was building to something wonderful. It’s a cry of lust, as much as it is one of love.

Johnny clearly has no idea of the sheer power he possesses here. He blinks back at her, bewildered. But he has had this effect on women before, so it shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise, though it’s sort of sweet that he hasn’t realised. And it can get him in trouble – one woman who has experienced his skills, Vivian, is even prepared to tell an absolute stonking lie because she fears she will never get near it again.

Ah yes, Vivian. Vivian Pressman, brilliantly and subtly played by Miranda Garrison (although on first viewing I was convinced it was British actress Lesley Joseph, of Birds of a Feather fame …), brings us to a different kind of sex represented in Dirty Dancing. In fact, there’s a lot of shagging in Dirty Dancing. It drives the plot as much as the dancing does. And a lot of general sexiness – everyone looks pretty up for it all the time. Even Baby’s parents, Jake and Marge Houseman, have a naughty twinkle in their eyes, to be frank.

The air of melancholy and loneliness, and faded glamour Vivian brings can be lost in the frenzy of the first few viewings, but it’s there and it’s important. When I first watched it, I was too overwhelmed by it all to really take her, and her storyline, in. But later in life I have grown quite fascinated by it.

It’s Max Kellerman’s introduction to Vivian early in the film that sets the tone. He watches her gracefully dancing with Johnny, a wry and sympathetic smile on his face as he explains to the Housemans that she is a ‘bungalow bunny’ – women who spend all week alone at Kellerman’s while their wealthy husbands work, arriving at the weekend only to ignore them further, choosing to play cards instead of dancing with their wives. It is clear that Vivian and Johnny have some form of quiet arrangement, and that she is one of the women ‘stuffing diamonds in his pockets’ that he refers to later in his speech to Baby about his experience of being sexually exploited in the resort. There are no sniggers, or jibes about older women. He doesn’t suggest that he is lowering himself, or is repulsed by her. There is an implied competition with Baby of course, which Baby wins, and yes, her youth is part of it, but also there is a sense that Vivian represents a jaded, toxic scene that we wish Johnny was not involved with, and Baby is his route out.

My only criticism of this storyline is that, as I have got older, I have wished to learn more about Vivian. There’s so clearly a real story there, and she would have things to say about life, men, and probably a whole lot else. Probably more than Marge Houseman, who doesn’t seem to have a lot going on, and even less to contribute, save for her final bark at her husband, ‘Sit down, Jake’, as Baby and Johnny take to the stage in front of everyone.

It took me a while to realise what was going on in one of the final scenes, where Vivian’s husband Mo offers Johnny some cash in hand for ‘extra dance lessons’ for his wife, because he will be busy playing cards all night. It took me even longer to understand that Johnny’s decision to reject the offer of cash (and therefore reject Vivian herself) from Mo Pressman, in front of her, motivates her to report him to his boss for stealing the purses and wallets that have been going missing around the resort. This then leads to Baby having to expose their affair by providing his alibi, while accusing the old couple, the Schumachers (who are found to be the real thieves). ‘I know he didn’t take them,’ she says falteringly, her eyes flicking briefly to her shocked father, ‘I know he was in his room all night. And the reason I know … is because I was with him.’ Wow – what a moment! Your heart could beat right out of your chest. She has just told everyone she is shagging the arse off her dancing instructor, right there, over breakfast.

There’s a lot to learn from this film when you are 11 years old. The mysterious and complicated world of adults was slowly coming into focus for me, but a lot still went over my head. There are layers I missed the first time I watched Dirty Dancing that would later reveal themselves with repeat viewings (even to this day, Vivian Pressman is now a pretty vivid character for me, rather than a slightly tragic side-show). I remember around this period (the early 1990s) hearing the phrase, ‘Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned’, for example, and gaining some insight into its meaning because of Vivian’s actions. To make herself feel better after Johnny’s rejection, she goes straight to nasty Robbie Gould, the waiter, and is discovered on top of him by Lisa, Baby’s sister, who arrives ready to let him pop her cherry. And all the while, a stone’s throw away in another cabin, Johnny and Baby are having another world-beating shag. It’s a busy night.

The moment where, in the harsh early morning light, a grim-faced Vivian, free of make-up, exits Robbie’s cabin, and, as she tucks her tights into her evening bag, looks up to see Baby and Johnny, the image of wholesome sexuality, kissing each other goodbye after a night of love and tenderness, has got to be one of the bleakest images in romantic cinema. In fact, it has saved me from some seriously ill-advised, on-the-rebound-style hook ups over the years – I just picture myself as Vivian at dawn, still in her party dress, no tights, wondering who’s using who, and it’s enough to make me order a cab home. Thank you, Viv.

So now, let’s deal with Neil. Poor Neil Kellerman represents all those men who inexplicably believe themselves to be catnip to women everywhere, when in fact they really couldn’t be less sexually appealing. Even I, aged 11, understood that this man is not the one you want, even though he is intent on telling you that he is all you could ever dream of. He is the absolute antithesis of Johnny, and a sexual wasteland. A date with him would leave you about as moist as a beech-nut husk stranded in the midday sun. Mere mention of the line, ‘I love to watch your hair blowing in the breeze’, to any woman familiar with the film and therefore the scene where Neil invites Baby to come for an evening walk, will result in an instant and uncontrollable physical reaction of pure cringing disgust. Try it – honestly, you’ll be amazed at the power those ten words can have. In fact, you don’t even have to have seen the film.

Crucially, Neil can’t dance. And this, to writer and retired dancer Eleanor Bergstein, essentially consigns any man to the sexual slag heap. For Bergstein, dancing is the greatest indicator of sexual prowess and compatibility. That’s why it’s called Dirty Dancing. Even more criminal than not being able to dance is not being able to dance while believing you can, a flaw Neil exhibits when he walks into the studio to talk to Johnny before the big end-of-season show. Baby tells him that she’s just there to have some ‘extra dance lessons’. We see Neil raise his hands, and gyrate a little, and utter the words, ‘I can teach you, kid,’ which will induce a vomit response in anyone who now firmly understands that dancing = sex. No, Neil, you can’t. No, no, no.