Полная версия

Our Bodies, Their Battlefield

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers,

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2020

Copyright © Christina Lamb 2020

Cover image: Two women mourn relatives and friends killed during the Višegrad massacres of Bosnian people in 1992, their bodies dumped in the River Drina. Photographed by Dijana Muminovic at the funeral in Potočari where 775 bodies exhumed from Lake Perućac were buried on 11 July 2010, during the 15th anniversary of the genocide in Srebrenica.

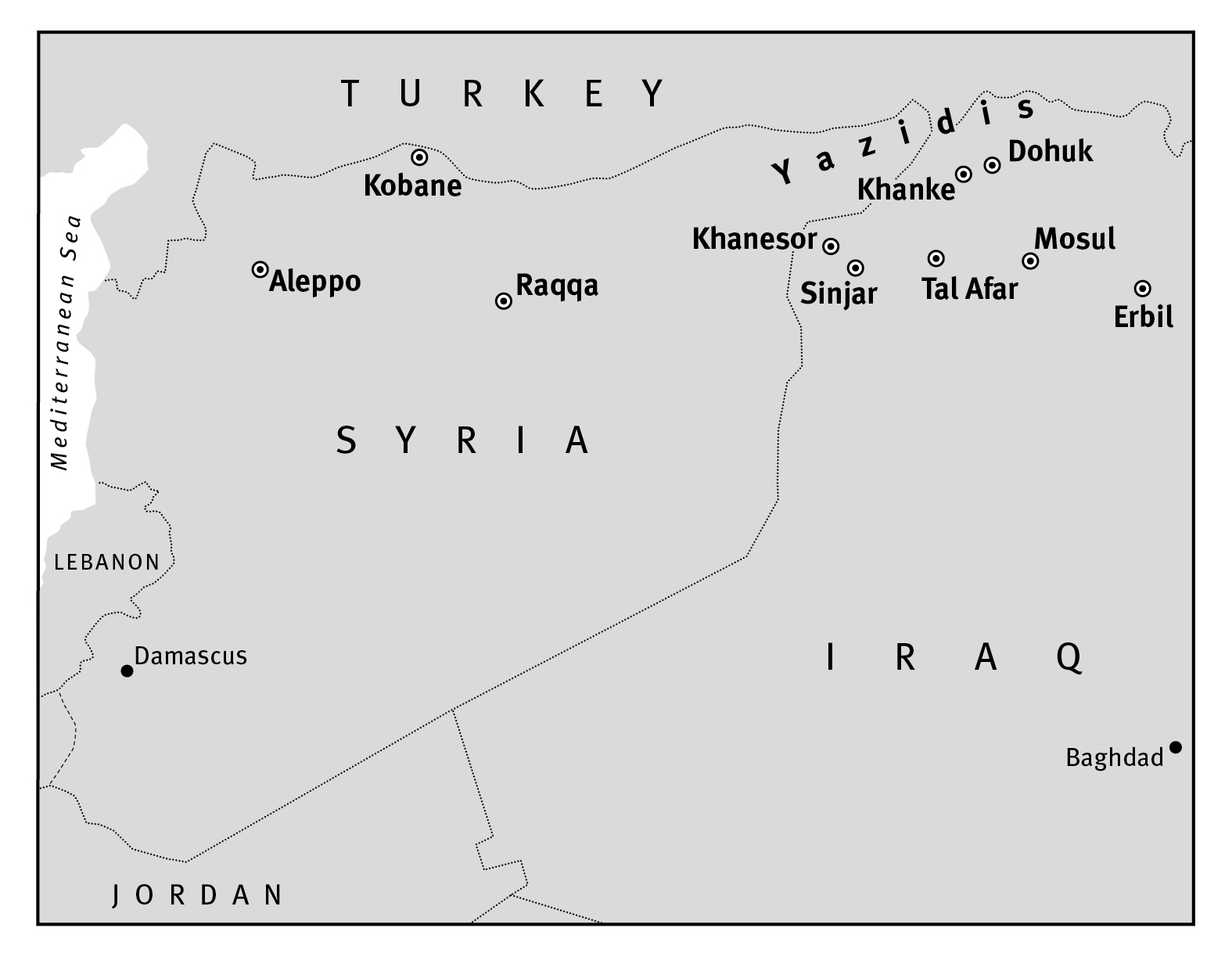

Maps by Martin Brown

Christina Lamb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780008300005

eBook Edition © March 2020 ISBN: 9780008300029

Version: 2020-02-12

Epigraph

We have given our most precious thing and have died inside many times but you won’t find our names engraved on any monument or war memorial.

Aisha, survivor of rape in the 1971 Bangladesh war

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Epigraph

5 Contents

6 Maps

7 Prologue: The Girl I Once Was

8 1 On Mussolini’s Island

9 2 The Girls in the Forest

10 3 The Power of a Hashtag

11 4 Queue Here for the Rape Victim

12 5 Women Who Stare into Space

13 6 The Women Who Changed History

14 7 The Roses of Sarajevo

15 8 This Is What a Genocide Looks Like

16 9 The Hunting Hour

17 10 Then There Was Silence

18 11 The Beekeeper of Aleppo

19 12 The Nineveh Trials

20 13 Dr Miracle and the City of Joy

21 14 Mummy Didn’t Close the Door Properly …

22 15 The Lolas – Till the Last Breath

23 Postscript: Giving the Nightingale her Song

24 Acknowledgements

25 Select Bibliography

26 About the Author

27 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivvix1234567891011131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303304305306307308309310311312313314315316317318319320321322323324325326327328329330331332333334335336337338339340341342343344345346347348349350351352353354355356357358359360361362363364365366367369370371372373374375376377378379380381382383384385386387388389390391392393394395396397398399400401402403404405406407408409410411412413

Maps

Argentina

Syria and Iraq

Bosnia and Herzegovina

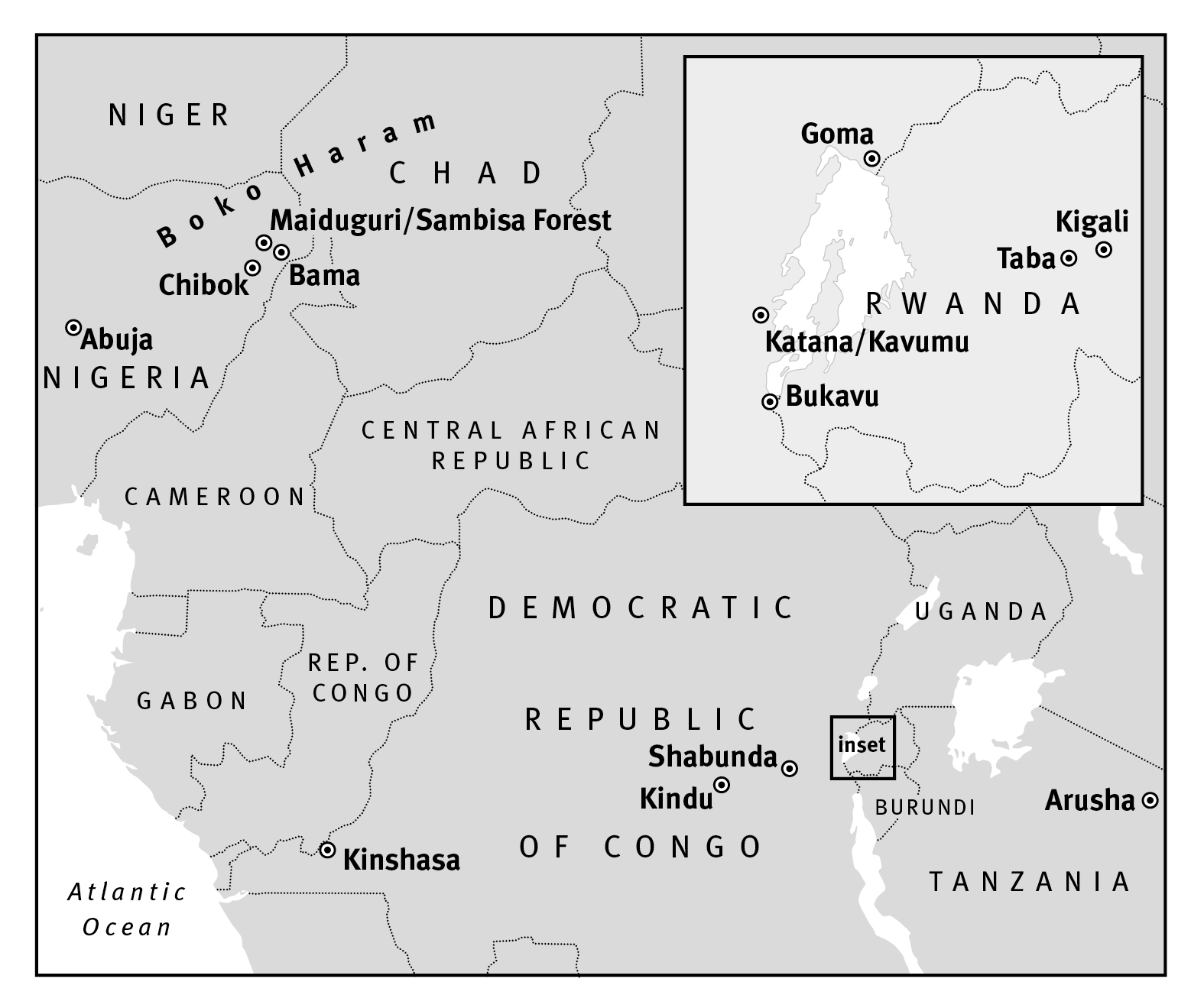

Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria and Rwanda

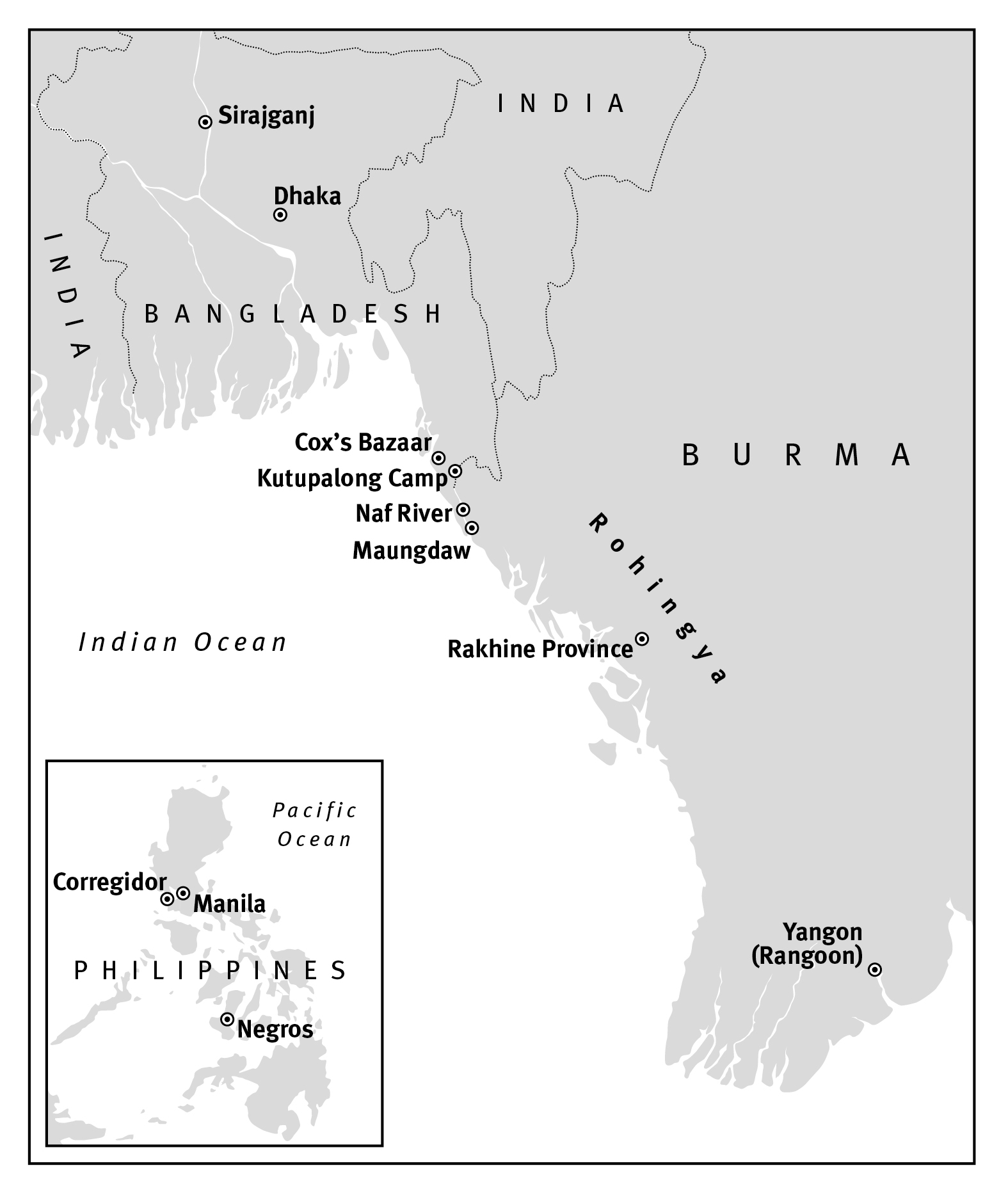

Burma and the Philippines

Prologue

The Girl I Once Was

They put the names in the bowl and began to draw them out. Ten names, ten girls. The girls quivered like kittens caught under a dripping tap. For them this was no lucky dip. The men pulling out the slips of paper were fighters from Islamic State and each would take a girl as a slave.

Naima stared at her hands, blood pounding in her ears. The girl next to her was younger than her, about fourteen, and mewling with fear, but when Naima tried to hold her hand, one of the men whipped off his belt and lashed them apart.

That man was older and larger than the others, around sixty, she guessed, with a belly cascading over his trousers and a vicious curl to his lips. By then she had been nine months in ISIS captivity. She knew none of them were kind but she prayed that one didn’t pick her name.

‘Naima.’ The man who read out her name was Abu Danoon. He looked younger, almost like her brother, the hair on his chin still fluff; maybe he would have less cruelty in his heart.

The draw continued. The fat man picked out the young girl next to her. But then he said something to the others in Arabic, pulled out two crisp hundred-dollar notes and slapped them on the table. Abu Danoon shrugged, pocketed the money, and handed over his slip of paper.

Minutes later the fat man was shoving her into his black Land Cruiser and driving through the streets of Mosul, a city she had once dreamed of visiting but which was now the capital of these monsters who had swept into her homeland and abducted her and six of her brothers and sisters, among thousands of others.

She stared through the tinted windows. An old man sitting on a cart was whipping a donkey to jerk it forward, and people were out shopping, though the only women in the streets were in black hijab. It was strange to see everyday life still going on for other people, almost like watching a movie.

Her captor was an Iraqi called Abdul Hasib and he was a mullah. The religious ones were the worst.

‘He did everything to me,’ she later recounted. ‘Hitting, sex, pulling my hair, sex, everything … I was refusing so he forced me and hit me. He said, “You are my sabaya” – my slave.

‘After that I just lay there and tried to float my mind above my body as if it was happening to someone else so he couldn’t steal all of me.

‘He had two wives and a daughter but they did nothing to help me. In between pleasing him I would have to do all the housework. Once I was washing dishes and one of the wives came and made me take a tablet – some kind of Viagra. They also gave me contraceptives.’

Her only respite came every ten days when the mullah went to Syria to visit the other part of their Caliphate.

After a month or so, Abdul Hasib sold her for $4500 to another Iraqi called Abu Ahla, a healthy profit. ‘Abu Ahla ran a cement factory and had two wives and nine children. Two of his sons were fighters with ISIS. It was the same thing, forcing me to have sex but then he took me to the house of his friend Abu Suleiman, and sold me for $8000. Abu Suleiman sold me to Abu Daud who kept me for a week then he sold me to Abu Faisal, who was a bomb maker in Mosul. He kept me for twenty days of raping then sold me to Abu Badr.’

In the end she was sold to twelve different men. She lists them one by one, their nom de guerre and real names, even their children’s names, all of which she had committed to memory, for she was determined they would pay.

‘To be sold like that from one to another as if we were goats was the worst,’ she said. ‘I tried to kill myself, to throw myself out of a car. Another time I found some tablets and took the lot. But still I woke up. I felt even death didn’t want me.’

I am writing a book about rape in war. It’s the cheapest weapon known to man. It devastates families and empties villages. It turns young girls into outcasts who wish their lives over when they are hardly begun. It begets children who are daily reminders to their mothers of their ordeal and are often rejected by their community as ‘bad blood’. And it’s almost always ignored in the history books.

Every time I think I have heard the worst I can hear, I meet someone like Naima. In jeans and a checked shirt with black trainers, her hazel-brown hair drawn back in a ponytail from a pale scrubbed face, she looked like a teenager, though she was twenty-two and had just turned eighteen when she was captured. We sat on cushions in her neatly swept tent in Khanke camp near the northern Iraqi city of Dohuk, one of row upon row of white tents that had become a home of sorts to thousands of Yazidis. We talked for hours. Once she’d started, she did not want to stop. And though sometimes she laughed, telling me of small acts of revenge she managed to inflict on her captors, she never smiled.

Before I left she turned her phone over to show me a passport photo inside the back cover. It was her as a smiling schoolgirl and the only thing she had left from a childhood in which she had never heard of the word rape. ‘I need to believe I am still that girl,’ she said.

Maybe you think of rape as something that has ‘always happened in war’, that goes along with pillage. Ever since man has gone to war he has helped himself to the women, whether to humiliate his enemy, wreak revenge, satisfy his lust, or just because he can – indeed rape is so common in war that we speak of the rape of a city to describe its wanton destruction.

A photo of Naima on her phone case (Alex Kay Potter)

As one of few women in a field that was still mostly male, I came into war reporting by accident and it was not the bang-bang that interested me but what went on behind the lines – how people keep life together and feed, educate and shelter their children and protect their elderly while around them all hell is breaking loose.

The Afghan mother telling me how she scraped moss from rocks to sustain her children as she shepherded them through the hills to escape bombing. The mothers under siege in the old city of East Aleppo who conjured up sandwiches for their children from fried flour and foraged leaves, and kept the children warm by burning furniture or window frames while streets around them were bombed into grey dust. The Rohingya women who carried their children through forests and across rivers to safety after Burmese soldiers massacred the men and burned down their huts.

You won’t find these women’s names in the history books or on the war memorials that we pass in our railway stations and town centres but to me they are the real heroes.

The longer I have done this job, the more disquieted I have become, not just at the horrors I have seen, but at the feeling we often only hear half the story, perhaps because those collating the accounts are generally male. Even now, histories of these conflicts are mostly told by men. Men writing about men. And then sometimes women writing about men. Women’s voices are too often left out. During the first part of the war in Iraq in 2003, up to the toppling of Saddam Hussein, I was one of six correspondents on the ground for my newspaper, the Sunday Times. When I read the reports afterwards, my three male colleagues and one of my two fellow women had not quoted a single Iraqi woman. It was as if they weren’t there.

It is not just the writers who see these lands of war as lands of men. Women are often excluded from negotiations to end wars even though study after study have shown that peace agreements are more likely to endure if women are involved.

I used to think we were safer as women in a war zone, that there was a certain honour toward women. But there is no honour among terrorist groups and merchants of evil. It seems clear that in many of today’s conflict zones it is more dangerous to be a woman. Over the last five years, I have seen more shocking brutality against women, in country after country, than I have witnessed in more than three decades as a foreign correspondent.

One only need visit the great galleries of the world or leaf through the classics to see that rape in war is nothing new. The very first history book in western history, by Herodotus, opens with a series of abductions of women by the Phoenicians then the Greeks and eventually the Trojans snatching Helen, setting off the Greek invasion of Asia and the Persian retaliation. ‘Plainly the women would never have been carried away, had not they themselves wished it,’ quotes Herodotus, in an early indication of how men would write history. In Homer’s Iliad, the Greek general Agamemnon promises Achilles women in abundance if he captures Troy: ‘… if the gods permit us to sack the great city of Priam, let him pick out twenty Trojan women for himself.’ Indeed the feud between the two men is caused by Agamemnon being forced to give up the woman he took as a ‘prize’ and trying to help himself to that of Achilles.

Rape and pillage was a way of rewarding unpaid recruits and for a conqueror to emphasise victory by punishing and subjugating opponents, what the Romans termed Vae victis (Woe to the conquered).

Nor was it just in ancient times. If we follow the ancient Greeks, Persians and Romans, Alexander the Great and the string of fair-haired blue-eyed children left across Central Asia, to the ‘comfort women’ of the Imperial Japanese Army and the mass rapes of German women by the Red Army in World War Two, we see that women have long been seen as spoils of war.

‘Man’s discovery that his genitalia could serve as a weapon to generate fear must rank as one of the most important discoveries of prehistoric times along with the use of fire and the first crude stone axe,’ concluded the American writer Susan Brownmiller in her ground-breaking account of rape, Against Our Will, published in 1975.

Rape is as much of a weapon of war as the machete, club or Kalashnikov. In recent years, ethnic and sectarian groups from Bosnia to Rwanda, Iraq to Nigeria, Colombia to Central African Republic, have used rape as a deliberate strategy, almost a weapon of mass destruction, not just to destroy dignity and terrorise communities but to wipe out what they see as rival ethnicities or non-believers.

‘We will conquer your Rome, break your crosses and enslave your women,’ warned Abu Mohammad al-Adnani, spokesman for the Islamic State, in a message to the West as ISIS fighters swept into northern Iraq and Syria in 2014, abducting thousands of girls like Naima.

A similar threat came from Boko Haram, an even more deadly terror group, as it stormed villages in northern Nigeria, killing the men and rounding up girls as ‘bush wives’ to be kept in camps to produce offspring, a new generation of jihadis in a chilling real-life version of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

‘I abducted your girls … I will sell them in the market, by Allah,’ declared Abubakar Shekau, after kidnapping hundreds of schoolgirls. ‘I will marry off a woman at the age of twelve. I will marry off a girl at the age of nine.’

I listened to women with unimaginable stories and as I poured my heart into trying to do justice in recounting them for the readers of my newspaper, I asked myself, over and over, How does this keep happening?

The intimate nature of rape means it is under-reported generally and even more so in conflict zones where reprisals are likely, stigmatisation common, and evidence hard to gather. Unlike killings, there are no corpses and numbers are hard to quantify.

But even where we do know, where courageous women come forward to describe their ordeals, rarely is action taken. It almost seemed as if rape was somehow trivialised and regarded acceptable when it occurred in war, particularly in far-off places. Or that we didn’t want to know. Sometimes after I tapped the last full stop and sent off my stories, editors told me they were too shocking for readers, or slapped ‘Disturbing Content’ warnings across the top.

To my astonishment the first prosecution of rape as a war crime was only in 1998.

Surely rape during war had been illegal for centuries? The first trial I could find was in the German town of Breisach in 1474 when Sir Peter von Hagenbach, a knight working for the Duke of Burgundy, was convicted for violation ‘of the laws of God and man’, a five-year reign of terror in which he raped and killed civilians as governor in the upper Rhine valley. His defence that he was ‘only following orders’ was rejected and he was executed. Some describe the twenty-eight-man panel set up by the Archduke of Austria as the very first international criminal tribunal; others argue that this wasn’t war rape as there was no conflict at the time.

One of the very first comprehensive efforts to codify the laws of war rejected the long-held view of rape as an inevitable consequence of conflict. President Abraham Lincoln’s General Orders No. 100, also known as the Lieber Code, issued in 1863 for the conduct of Union soldiers in the US Civil War, strictly prohibited rape ‘under penalty of death’.

In 1919, in response to the atrocities of the First World War, including the massacre of hundreds of thousands of Armenians by the Turks, a Commission of Responsibilities was set up. Rape and forced prostitution were near the top of a list of thirty-two war crimes.

That didn’t stop it in the Second World War. Outrage at the horrors of that war, when all parties to the conflict were accused of rape, led to the victors establishing the first international tribunals in Nuremberg and Tokyo to prosecute war crimes. Yet there was not a single prosecution for sexual violence.

Not even an apology. Instead silence. Silence on the sexual slavery of the comfort women. Silence on the thousands of German women raped by Stalin’s troops which I read nothing about in my school history books. Silence too in Spain where General Franco’s Falangists had raped women and branded their breasts.

For too long this has been the reaction. War rape was met with tacit acceptance and committed with impunity, military and political leaders shrugging it off as if it were a sideshow. Or it was denied to have ever happened.

The second paragraph of Article 27 of the Geneva Convention adopted in 1949 states: ‘Women shall be especially protected against any attack on their honour, in particular against rape, enforced prostitution, or any form of indecent assault.’

For decades it has been the world’s most neglected war crime. It took rape camps being set up again in the heart of Europe for the issue to get international attention. Like many people, the first time I heard of sexual violence in conflict was in the 1990s during the war in Bosnia.

The resulting outrage suggested the end of the tacit acceptance of rape in war that had existed historically. In 1998, the same year as the first conviction, rape as a war crime was enshrined in the Rome Statute which established the International Criminal Court.

On 19 June 2008, the United Nations Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1820 on the use of sexual violence in war, indicating that ‘rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute a war crime, a crime against humanity, or a constitutive act with respect to genocide’.

A year later, the Office of the Special Representative of the UN Secretary General on Sexual Violence in Conflict was established.

But twenty-one years after the creation of the International Criminal Court, it had not made a single conviction for war rape. The only one had been overturned on appeal.

Having these crimes on the statute books is a start, but clearly no guarantee of enforcement or even proper investigation. By their very nature these crimes are often not witnessed and direct orders not written down, and hard for victims to prove or admit to. The situation has not been helped by the fact that investigators are often male and not always adept at eliciting testimony on such sensitive matters. Decision-making positions are often held by male prosecutors or judges who do not see sexual violence as a high priority compared to mass killings, sometimes even suggesting the women ‘asked for it’.

Sadly, the fact that the international community now recognises that sexual violence is often used as a deliberate military strategy, which can be prosecuted, has ended nothing in many places across the world. The 2018 report of the UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict listed nineteen countries where women were being raped in war and named twelve national military and police forces and thirty-nine non-state actors. This was by no means a comprehensive list, it noted, but ‘where credible information was available’.

And then there was #MeToo. For many of us 2017 may be remembered as a turning point for speaking out about sexual violence. The emergence of the Me Too movement following the allegations by a string of actresses and production assistants against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein lifted the guilt and shame so many assaulted women felt and emboldened them to speak out.

Like many women I followed the Me Too movement with a mixture of delight and horror. Delight that so many women were speaking out and refusing to take more of the harassment many of us middle-aged women once took for granted. Horror that sexual violence was so prevalent – one in three women experience sexual violence in their lifetime. It knows no race, no class, no borders: it happens everywhere.

But I also felt a certain unease. What about the women who do not have resources for lawyers or access to media? What about those in countries where rape is used as a weapon?

As we saw with those who spoke about Harvey Weinstein, even strong independent women in the liberal west who speak out about sexual predators do so with extreme difficulty and dread. Often they are pilloried in the press and have to go into hiding, as happened to Dr Christine Blasey Ford, the lawyer who alleged she had been sexually assaulted as a teenager by Brett Kavanaugh, nominee for Supreme Court judge.

Imagine then women with no money or education in lands where those with the gun or machete exert the power. Not for them rape counselling or compensation. Instead they are often the ones condemned. Condemned to a lifetime of trauma and disturbed nights, problems in forming relationships, not to mention physical damage, perhaps a childless existence – they may even be ostracised from their communities, what one referred to as ‘slow murder’.