Полная версия

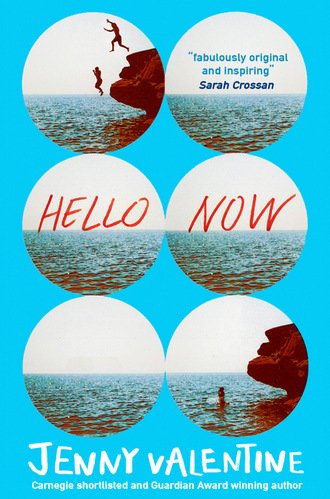

Hello Now

HELLO NOW

Jenny Valentine

First published in the United States of America by Philomel, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC in 2020

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2020

Published in this ebook edition in 2020

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Jenny Valentine 2020

Cover photos courtesy of Stocksy.com

Cover design by Dana Li

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

All rights reserved.

Jenny Valentine asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007466498

Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008382360

Version: 2020-03-09

For Jeff

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Novo

Chapter 1: Jude

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Novo

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Novo

Books by Jenny Valentine

About the Publisher

NOVO

WHEN IT HAPPENS, I DON’T FEEL IT. I NEVER feel it. I just sleep. And they wash away, the things I’ve held on to, all of them. I let them go, leave them unchanged, and they are clean and new and nothing and then I am back. Never the same place – sometimes the cut and pulse of human traffic, sometimes a vast empty space. Anywhere and Always. The hot bite of dust, a blanket of snow. Soft opening of a morning or deep, sharp night. Sometimes before Now, and during, and also after, just the land holding bodies and the birds rising up over the sea. Square one, in all its different disguises. Always moving. Always alone.

I never forget what I am looking for, over and over, somewhere in that black-hole sleep. The one that keeps me. The one I can keep. My hook. A face at a window, the air in a bubble, a bird in a cage. Consequence. Purpose. Belonging.

A street. Here. Now.

Will it be this time? Will it be never? I get out of the car, know my name and my age, my own hands, all my histories, same as ever. Quiet facts come to me like old finger drawings on glass, only traces. These trees. This house. This beginning. I stand at the side of the road, taking it all in, hoping and hoping. And I wonder, not for the first time, if it has some kind of start, this life, and who’s controlling it, and if it is ever, ever going to stop.

***

1

JUDE

I’VE NEVER BEEN INTO LOVE STORIES. TOO MUCH sugar, too much gloop, same reasons I don’t like candyfloss or fondue. Only so many sunsets and hand-holds and ever-afters I can stomach, honestly. Seven words for it in Greek. Twenty-seven in Tamil. All those subtleties, like Eskimos and snow, and we just have this one four-letter word and expect everyone to make a religion out of it.

I’ve never been into magic either, not the made-up miracle kind. Not when there’s the miracle of actually existing to deal with, the magic of infinitely small particles, the exact same particles, coming together to make a human being or a seashell or the Earth’s atmosphere or a cup of tea or just a log. There’s magic in putting one foot in front of the other, isn’t there? There’s magic in a foot, come to think of it. It’s everywhere. Even to be here is so much.

That’s what I knew about love before, when it was still just a spectator sport for me. Here’s what I learned by osmosis. That people spend their time wishing so hard to be with someone else they forget how to be a proper version of themselves. That we are all too ready to give up our independence, ache to hand it over gladly like it’s nothing, and make someone else responsible for our happiness, someone way less invested, way less qualified than us.

That kind of love is a selfish thing, transactional, an exalted kind of laziness, and that’s why nobody says ‘I love you’ without wanting it said back.

But love is not a transaction. Four-letter love is a big black hole and that’s why you fall into it. The finest bubble, the best dream, where you don’t want to wake up, not for a second, not ever, because you know you have to, you know you will, and that then, nothing else will come close. It makes all the everyday miracles duller and more ordinary, just from having been there, from having gone. That kind of love and magic feel the same. I know that now, for a fact. I’m an expert on the things I used to say didn’t exist.

Other loves aren’t a difficult ask for me. I love my mother. That goes without saying, even when I don’t like her. I love London, and my old house and all the days of my childhood, all my friends. I love the sea, and walking on its edges, and the taste of salt and vinegar on a hot chip. I love dancing in dark rooms and getting lost in a long book, and you’ve got to love laughing, everybody loves a decent joke. I love strangers and the internet and I love snow and sand and new places. I love obvious signs of loneliness, for some reason, and old people and young people and most dogs and the things we say to each other and singing and all types of fire and the underdog and a lot of movies, even bad ones, and marmalade on dry brown toast and clean sheets and ginger tea and I am really only just getting started.

Love is everywhere too.

I could fill this whole page with the things I love. I could carry on thinking of new ones without stopping, twenty-four hours a day, until I die. But all of them, standing together, armed to the teeth and in organised ranks with me leading the charge, still couldn’t have prepared me for Novo. Of having him. Of having him with me, alone, the great weight of his arm. And then not.

When I think about that, I feel the impact in my chest, the air pushed from my lungs, the clean sharp break of all the bones in my body. It hurts. It’s a violent equation, love plus loss. I don’t want that to be true. But I don’t know how else I’m supposed to put it.

Look how hard it hit me. I’m bleeding love story all over the place.

***

2

IN THE BEGINNING, BEFORE I KNEW THAT I DIDN’T know much about anything, my mum and I moved into a house with a stranger in it. It was a big house in the small town she grew up in (and then left, by the way, swearing never to return) on a street where fat-knuckled trees pulled at the pavements with their roots, and the average age was well over fifty, and nobody said very much.

The stranger wasn’t hiding in the attic or lurking under the floorboards. He wasn’t a blind purchase. His name was Henry Lake, and he came with the sale, refusing to budge. A sitting tenant, Mum said. A fly in the freeholder’s ointment. A stick in the capitalist mud. ‘Something we can both get behind,’ she said, which I told her was optimistic, and, at the time, frankly, pushing it.

She remembered the street from her childhood, sort of, and that the houses were beautiful. And massive. And had gardens that sloped right down to the sea. This meant less than nothing to me – five hours’ drive from my current definition of home – and I told her that too. But because of this stranger still living in it, this house on the sole of the boot of the country was a whole lot cheaper than anything else she’d managed to find. Thanks to Henry Lake being there, it was the one she could afford, so it was happening, we were going, end of discussion, and that was that. It’s thanks to him and because of him that so much other stuff happened too, and is still happening, but I’m getting ahead of myself, and when I started writing this down, that’s one of the things I swore I wouldn’t do. This particular love story is bewildering enough as it is without me helping.

We didn’t have a separate front door or anything. Henry Lake’s rooms were on the middle floor, and we were just meant to move in and live around him like the white surrounds the yolk of an egg. I said that was flat-out ridiculous, and when Mum told me to get used to it, every cell in my body screamed never.

‘Seriously?’ I said. ‘No locks on the doors? What are you thinking? What if he’s unhinged? For all we know he could be a killer,’ and, while I was saying it, something dark scuttled down an alley in my stomach, this idea that I might be right, that this was my fate, set already, bound to happen. Game over. Job done.

‘Plus it’s miles away,’ I said again, into the void Mum left by not responding. ‘No joke, Mum. You’ve lost your actual mind.’

‘No, Jude,’ she said, folding into her chair like a dropped flag. ‘I’ve lost everything else.’

Everything else translated loosely as Mark, her boyfriend for just under a year, her latest Holy Grail, her answer to just about every question under the sun. Mark wasn’t all that, but he was all right. He was pretty nice to her and he didn’t act like I was the unwanted guest or the icing on the cake, unlike some previous boyfriends I could mention. He worked in insurance and you’d think from the way she batted her eyelashes at him when he droned on about assets and premiums that a man in insurance was all she’d ever wanted, the sum total of her heart’s desires. My mum is a very good actor. She couldn’t give a shit about insurance. What she wants is not to be alone.

Anyway, Mark had taken his assets and premiums elsewhere, and because he was also our landlord, while we’d lived with him, that included the roof over our heads. Mum was still in phase one, acting like it was the end of the world, which it blatantly wasn’t. She was doing that thing she does where she just takes for granted that it’s me and her against the world, without even asking if I was on her side for this one. She said, ‘Can you believe this is even happening to us?’ and when I pointed out it was actually her decision to drop everything and drag me to a sad-sounding, pensioner-dense, end-of-the-road, far-as-the-eye-could-see whites-only seaside town from her distant past, she welled up and went all defenceless wounded puppy on me, because it works every time and she knows it. Takes the sting right out of my fight.

‘A new start,’ she called it, without asking me if I even wanted one, because it was obvious I didn’t, and I said, ‘Haven’t we had our share of those?’ One for every Mark that turned out not to be God’s gift after all. Such an over-investor. She might as well have invented the concept of eggs in one basket. Eight full new starts, and three or four half-hearted versions, where I didn’t have to move schools at least, just took way longer to get there and was always late for everything, always left behind. It was always like that, since my dad, I guess, who was the first but who came and went just like the others. A link in a chain, and a stranger now. If I saw him in the street I wouldn’t know him. Sad but true. I’ve made my peace with that.

This time, phase-one Mum was really shaking things up. Maybe I should have been more positive. She was doing it by herself, after all. Declaring independence. But at the time, she knew how I felt about it. I reminded her it had taken work to make even the few friends I had. I said we both knew there was no way I’d be able to keep them, not at that distance. I wanted that to count for something. I was looking for mercy, but that well was dry.

‘You’ll get new friends,’ she said, like I could just pick some out in a gift shop, like that was how easy it was, and it stunned me, the ignorance, the carelessness of that.

‘Ouch,’ I said. ‘Blunt.’

‘What?’ she said. ‘You’re good at it.’

‘Yeah? Because I’ve had to be.’

‘Well, life teaches us the skills we need,’ she said, trying to make a virtue out of throwing me in at the social deep end every time a new Prince Charming withered on the vine.

When I was eight and we were moving for the third time in a year (a real bad patch – Jim, I think, then Danny, then Joe) I tried to stop the move from happening by tying everything in my room down with string. I got a ball of it and I cat’s-cradled the hell out of my bed and my radiator and my toy cupboard and my bookshelf and then I waited like Charlotte in the middle of her web to see what I’d spelled. Mum used to tell that story to people like it was funny. I’ve heard it a hundred times over the years, and I’ve smiled and nodded and put up with being laughed at. She even laughed at me when it happened. She opened the door and she opened her mouth and threw her head back and I could see the undersides of her teeth, the biting edges, and I remember thinking, How could she? because it was the opposite of funny to me. I was dead scared of losing something. I didn’t want things to change. Not again. But they did, and they do, and I guess I started learning way back then that you can’t stop your world from turning, however tight you tie it down, however hard you try.

So. Here we were again. Move number thirteen. Mum was on her own, not counting me. She was acting out and we were packing up and I was all set to repeat, all set to be brand new in another place. I could feel it coming – the unknown, the sudden onset of lonely. First-world problems, sure, but still. Problems all the same.

***

3

THE ESTATE AGENTS AND LAWYERS WEREN’T beneath making the prospect of this Henry Lake’s death a kind of sweetener on the deal. Our sitting tenant was old, apparently, and not in great shape, and I heard one of them tell Mum on the phone that she wouldn’t have too long to wait to get the whole house to herself. A euphemism if ever I heard one. ‘Health problems,’ he said, the same way he probably said, ‘detached garage’ and ‘en-suite bathroom.’ I listened and I sat on my hands and tried to laugh, which is the only way to deal with outrage sometimes, the only safe way to breathe out and be gentle and just watch it pass.

When she hung up I said, ‘Isn’t it a hundred different kinds of not right that a real-life, living person would make a place worth less money instead of more? Don’t you think?’ but Mum was still in high drama, post-break-up crisis mode. She said, ‘I’ve got other things to think about, Jude, more immediate and pressing things, like finding a real place to live.’ And I suppose I’ve got more immediate and pressing things to say now, and that’s part of the trouble, and why the value of a human life ends up having to wait for later.

Last Supper time in the flat, she pushed spaghetti hoops around on her plate instead of eating them, one of those new role-reversal moments that made me want to tell her to sit up properly and stop playing with her food.

‘Don’t worry,’ she said, without commitment, kind of absent behind the eyes, like she had been for a while. ‘Everything’s going to be fine. Mr Lake is a nice man on a nice street.’

‘Yeah. So was Crippin,’ I said, and for a second I thought she might crack a smile, but she didn’t, just scowled, like I was trying to trick her into it.

She stood up to scrape the rest of her spaghetti hoops into the bin, the back of her head more expressive of her feelings than you’d think possible. Just a nudge and the whole lot slid off the plate in one slimy clump, a colony of something, half reluctant, half alive, which put me right off finishing mine. I watched her grip on the fork, waited for her knuckles to go from bone-light back to skin, and then I asked her again why a house was worth less money with another human being inside it, how that could ever be allowed to happen. On a good day that might have been the start of a proper conversation about plutocracies and trickle-down economics and the politics of homeownership and the poverty gap, and I would have learned something. But we weren’t back to good days yet. No such luck.

‘Oh, you know,’ she said without turning round. ‘It’s the way of the world. People don’t like to share.’ Like that nailed it, like it was all that needed to be said.

‘Is that it?’ I said, and she said, ‘Pick your side, Jude. Is he a human being or an unhinged killer?’

‘Or both,’ I said, and she glared at me and the angry pulse in her jaw ticked.

‘This is the last time, Mum. I’m not doing this with you again, I swear.’

‘Fine with me,’ she said on her way out of the room, but neither of us meant it, not really, and that was another one of our new-style low-quality splinter-family mealtimes over and done with.

***

4

ON THE DRIVE DOWN I’D HAD LESS THAN TWO hours of sleep, and no breakfast. The air conditioning in the car had been broken since forever and the stereo was playing up. Mum said, ‘If it rains, we’re screwed,’ because the windscreen wipers were worn out and basically useless. She wasn’t even sure if the car was going to start, or keep it together long enough to get us there, so on top of not wanting to go, there was the stress of not knowing if we’d actually arrive.

‘Yay,’ I said. ‘Road trip.’

I can’t read in a moving car because it makes me want to throw up. In fact, it’s just about the only place on the planet where a good book does nothing for me, my own special version of hell. I’d dropped my phone the week before, third time in as many months, and it was properly smashed, no real hope of repair, tiny hidden cogs and chips exposed like so much guts, so close to useless in terms of in-car entertainment. I’d tried wrapping it up with tape to hold all its innards together, and the camera still worked, on and off, but it was like looking at everything through a shattered glass eye and half the time it just froze and stared me out like it was annoyed with me, which it probably was. Mum said she wasn’t paying for another one because I was (quote) pathologically incapable of looking after it, and she was twenty-four hours a day losing the plot about money anyway, so, job done.

Out past the M25, I told her about my (about to be ex) friend Roma’s grandad telling us out of the blue that he’d been an extra in the original Star Wars. And this film I’d seen online about how the advertising industry got inside everyone’s heads in the 1950s thanks to some pioneering PR guy who was related to Freud. And a book I’d started reading about the history of the atmosphere. All perfect openers, in my opinion, and there was a time they’d have worked like a charm, but this wasn’t one of them. Mum wasn’t biting, so I got desperate and asked her who her favourite Simpson was. That’s when she breathed out through her mouth like a cross horse and told me to be quiet for just one minute, if that was at all possible, so she could think.

Rude.

Most of the known world says that people my age are hard to communicate with, but really? They should try getting through to my mother when she’s driving. The silence that descended was familiar, well worn, the wonder-what-(insert name here)-is-doing-now-and-who-with silence. I looked the other way out of the window after that, kept my mouth shut out of principle, missing home – the phone shops and the flower stall, the dry cleaner’s and the tube station and the fried chicken place whose window was always broken, never fixed, not for long anyway. The view from the road felt spare and oddly empty. There wasn’t much else to look at on the way down but fields and other cars and clouds and sky.

***

5

IT DIDN’T RAIN, AND THE CAR GOT US THERE IN one piece, and even though I wasn’t grateful, I could see straight off that the street was way tidier than we were used to, another level – quiet and wide and tree-lined, high up in the town with a view of the sea, pure blue that day, same as the sky. No traffic jams. No autopsied mopeds or abandoned fridges, no weatherproof all-season dog shit or stained mattresses or boarded-up windows. A sharp salt smell and this strong bright light and palm trees. Palm trees. The wind leaned hard against the car like it didn’t want us to get out, knew right away that we didn’t belong. Turn back, it said, big mistake, don’t even think about stopping, and I still wonder sometimes what life would be like if Mum had heard it, if she’d turned the car round and just obeyed. I let out a low whistle and watched her force the dark back down in her eyes. I know she felt it suddenly, the impact of her decision, right then, middle-aged and defeated, with me in tow. Not what you’d call triumphant. Not exactly a lap of honour. If I’d known what to say to her then, what would have helped, I like to think I might have said it. But then again, maybe not. We should all be given a manual at birth for that sort of thing.

I started fishing around under my seat for the steering wheel lock, and she said, ‘I wouldn’t bother, Jude. No one’s going to pick on our heap-of-crap car in this ocean of high-quality metal,’ and she had a point. The low-budget new neighbours had definitely arrived.

We got out. The wind whipped my hair into my mouth and back out again, turned Mum’s jacket into an airbag. The house with Henry Lake in it stood out as much as we did, a stain on the neat white terrace like a rotten tooth. All manner of crap was crammed in the dustbins and stuffed in the uncut hedges. The roof was pockmarked with moss and weeds and bird shit. Some clever kind of tree had taken root up there, getting a head start on all the others, and I had some respect for that. Henry Lake’s elongated shadow scuttled across an upstairs window. A gull on the chimney pot opened its throat and cried, launching itself into the air above our heads. I heard the sail-crack of its wings, saw its rain-cloud underside as it circled, head tilted, gimlet-eyed, watching. I hate being the centre of attention. I wondered how many other pairs of eyes there were on us right then, sizing us up, passing judgement. I could feel the blood needling in my fingers, the jittering bones in my ears. I liked our old life. I liked our last flat. I knew how to get there from my friends’ houses, from all the places we went out. I knew where every single thing was kept. Me and Mum and Mark were happy there, sort of, until we weren’t. And it didn’t have an old stranger curled up in the middle of it, like a maggot in a peach.