Полная версия

Charlie Bone and the Shadow of Badlock

‘I’m sorry, I don’t think my parents can help,’ Benjamin apologised.

‘I’m pretty sure they can’t.’ Maisie turned away and led Benjamin down a dim passage. ‘This is one of those disappearances that normal people couldn’t hope to solve.’

‘But I’m normal,’ Benjamin reminded her.

Maisie sighed. ‘Well, I know. But you’re a friend, and you could get one of the others: the endowed ones – or whatever they call themselves.’

‘Children of the Red King,’ Benjamin said quietly.

They had reached the cellar door, which stood wide open. Maisie beckoned to Benjamin and pointed into the cellar. Benjamin looked down into the murky underground room. Maisie nodded encouragingly. Benjamin didn’t like cellars, nor did Runner Bean. The big dog began to whine.

‘Do I have to?’ Benjamin asked.

‘It’s down there,’ said Maisie in a hushed voice.

‘What is?’

‘The painting, dear.’

Benjamin uttered a very slow ‘Ooooh’ as he realised that Charlie must be travelling. ‘He hasn’t really disappeared then.’

‘This time he has,’ said Maisie solemnly.

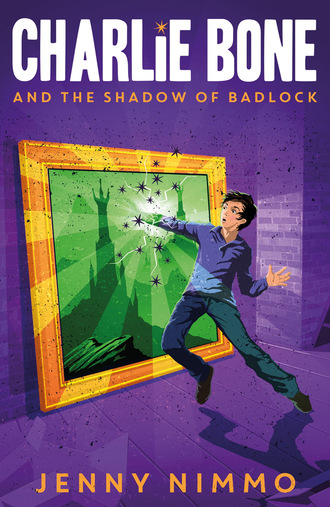

Benjamin stared into the cellar. He descended three, four steps until he could see the whole room. A dim light, hanging from the ceiling, showed him a disused cupboard, broken chairs, curtain poles, piles of newspapers and magazines and large black plastic bags filled with bulging objects. And then he saw the painting. It was standing against one of the walls, beside an old rolled-up mattress.

A small shadow flickered over it, and Benjamin saw that a white moth was hovering round the light bulb. All at once, the moth swung away and vanished. Benjamin went to the bottom of the steps and walked over to the painting. Runner Bean scrabbled down after him. He was panting very heavily and occasionally emitted a nervous whine.

The painting gave Benjamin the shivers. He was, as Maisie had admitted, a normal boy, so he experienced none of the insistent tugs that Charlie had felt, nor did he feel or hear the moaning Badlock winds. He did, however, get the impression that the almost photographic reality of the painting showed a place that had not been imagined but copied faithfully. It existed. Or did, once. With its dark towers, sunless sky and looming mountains it was certainly a hostile, sinister country.

There was a green scrawl in the bottom right-hand corner of the painting. ‘Badlock.’ If Badlock really was a place, it was not somewhere that Benjamin would have wanted to visit. So why did Charlie ‘go in’? It was deserted and, as far as Benjamin could remember, Charlie had always needed first to hear a voice, and then to focus on a face, before he entered a picture. And in all the time Benjamin had known about his friend’s endowment, Charlie had never actually disappeared. His physical presence had always remained in the present, while his mind roamed the world behind the pictures.

‘What d’you think’s going on, Ben?’ asked Maisie from the top of the steps.

Benjamin shook his head. ‘Don’t know, Mrs Jones. Where’s Charlie’s uncle?’

‘Paton? Bookshop,’ said Maisie. ‘Where else?’

‘Think I’ll go over there. Mr Yewbeam will know what to do.’ Benjamin turned towards the steps.

Runner Bean didn’t follow his master, but stood before the painting in an odd attitude, his head on one side, as though he were listening to something. He gave a low, mournful howl. And then, before Benjamin’s very eyes, the yellow dog became a smaller, paler version of himself.

‘Runner?’ Benjamin leapt towards his dog. He touched the tip of Runner Bean’s tail, which was standing out, as stiff as a broom, but in less than a second the tail had melted away and with it the whole of Benjamin’s beloved dog.

Benjamin shrieked, ‘RUNNER!’ just as the front door slammed.

‘Oh, my giddy aunt!’ Maisie clapped a hand over her mouth.

She was roughly pushed aside by Grandma Bone, who had suddenly appeared beside her.

‘What on earth is going on?’ demanded Grandma Bone.

Benjamin stared up at the two woman. Maisie was shaking her head, her eyes were very wide and her eyebrows were working furiously up and down. She seemed to be warning him. Distraught as he was, Benjamin began to think, fast. It was always understood by Charlie and himself that Grandma Bone must know absolutely nothing about what went on, especially if it had anything at all to do with Charlie’s travelling.

Grandma Bone had caught sight of Maisie’s eyebrow-wriggling. ‘What’s the matter with you, woman?’ she snarled.

‘Surprise,’ said Maisie. ‘So surprised. Thought we heard a rat, didn’t we, Benjamin?’

Benjamin nodded vehemently.

‘I thought I heard a bark.’ Grandma Bone glared suspiciously at Benjamin. ‘Where’s your dog?’

‘He . . . he didn’t come with me today,’ said Benjamin, almost choking with distress. Could Grandma Bone see the unwrapped painting from where she stood? He didn’t think so.

‘Unusual. Not to bring your dog. Thought it was your shadow?’ The tall woman turned on her heel and walked away, adding, ‘I’d come out of that cellar if I were you. It’s more than likely the rats’ll get you. Where’s Charlie, by the way?’

‘Gone to the bookshop,’ Maisie said quickly. ‘And that’s just where Benjamin’s going, isn’t it, Ben?’

‘Er – yes.’

Benjamin dragged himself regretfully up the cellar steps. He felt that he was betraying Runner Bean, leaving him trapped inside the awful painting. But what else could he do? Charlie’s Uncle Paton would provide an answer. He usually knew what to do when things went wrong.

Maisie saw Benjamin to the door. ‘Take care, dear,’ she said. ‘I don’t like to think of you alone in the city, without your dog.’

‘I am eleven,’ Benjamin reminded her. ‘See you later, Mrs Jones.’

‘I hope so, dear.’ Maisie closed the door.

Benjamin had taken only a few steps up the road when he became acutely aware that part of him was missing. The dog part. He’d been without Runner Bean before, when his parents took him to Hong Kong. But this was different. This was in a city where almost nothing was ordinary. Without warning, people could suddenly disappear, street lights could explode, snow could fall in summer.

Ingledew’s Bookshop wasn’t far from Filbert Street, but today it felt as though there was a huge chasm between Benjamin and safety. He was halfway down the High Street when he saw two children on the other side of the road. Joshua Tilpin, a small, untidy, sullen-looking boy, shambled beside his taller companion, a boy with a pale greenish complexion and an odd lurching walk. Dagbert-the-Drowner.

Pretending he hadn’t seen them, Benjamin walked nonchalantly on, but from the corner of his eye, he saw Dagbert nudge Joshua and point across the road.

Benjamin lost his nerve. Instead of continuing up the road, he darted into a side street. For a few minutes he stood in the shadows, watching the two boys. He was being silly, he told himself. Why should he be afraid of two boys from Charlie’s school? He hardly knew them. All the same, they gave him the creeps. Joshua had a reputation for making people do things against their will; not hypnotism, exactly; they called it magnetism. As for Dagbert, he drowned people. Recently, he’d tried to drown Charlie in the river.

Glancing up the street behind him, Benjamin was relieved to find that he knew where he was. He began to run.

‘What’s up, Benjamin Brown?’ called a voice. ‘Lost your dog?’

Benjamin didn’t look back. Joshua and Dagbert must have raced across the road and followed him.

‘You’re not frightened of us, little Ben, are you?’ Dagbert shouted. ‘Where’s Charlie?’

Almost falling over his own feet, Benjamin bounded into a cobbled square. In the centre of the square stood an old detached house. It was surrounded by a low wall and a weedy garden. Nailed to the gate was a weathered board that read, ‘Gunn House’. The rest of the board was filled with music notes: crochets, quavers, minims and semibreves, though one hardly needed the musical notation to know that a family of musicians lived here. The noise coming from within the house made it obvious. The walls shook with the sound of drums, violins, flutes, cellos and singing voices.

Benjamin pressed the doorbell and a deep recorded voice announced, ‘DOOR! DOOR! DOOR!’

The Gunns’ door-voice always unnerved Benjamin, but then a tinkling bell would have been drowned by the music, and visitors would have waited on the step in vain.

The door was opened by Fidelio Gunn, a violin in one hand and a bow in the other. ‘Hi, Ben, where’s Charlie?’ said the freckle-faced boy.

‘Oi!’ came a shout behind Benjamin.

‘Charlie’s – er –. Can I come in, PLEASE?’ asked Benjamin.

Catching sight of Benjamin’s pursuers, Fidelio said, ‘You’d better.’

Benjamin leapt into Gunn House and Fidelio slammed the door.

‘What’s going on, Ben?’ Fidelio led the way into a chaotic kitchen. A grey cat was eating the remains of a breakfast that still hadn’t been cleared from the table, and a woman in a long colourful skirt was singing at the sink. A small freckle-faced girl tuned her violin beside her.

‘Pianissimo, please, Mum!’ Fidelio shouted. ‘Mimi, take your violin somewhere else.’

Mrs Gunn looked over her shoulder. ‘Benjamin Brown,’ she sang. ‘What a surprise! Can’t believe my eyes! Where’s the dog of impressive size?’

‘Where’s Charlie Bone?’ asked Mimi, plucking a string.

‘Look, Benjamin is a person in his own right,’ said Fidelio. ‘He doesn’t have to have an appendage.’

‘A what?’ said Mimi, plucking another string.

‘An attachment,’ replied her brother. ‘Benjamin’s dog is not permanently attached to him, nor is Charlie. Sit down, Ben.’

Benjamin pulled out a chair and sat down. Feeling hungry, he picked up a piece of dry toast and took a bite out of it.

‘Pudding has just licked that,’ Mimi informed him.

Benjamin eyed the grey cat and sadly replaced the toast.

Fidelio took a chair beside him and leaned forward, his elbows on the table. Mimi stopped plucking at her violin and perched on the other side of the table. Mrs Gunn hummed softly while she scraped at something in the sink.

‘What’s happened, Ben?’ asked Fidelio. ‘It’s not just those morons outside, is it?’

‘No.’ Benjamin looked at Mimi.

‘Mimi always knows what’s going on,’ said Fidelio. ‘You can’t keep secrets from her, but she can keep a secret, can’t you, Mims?’

My lips are already sealed.’ Mimi gave Benjamin a big, sealed smile.

‘OK.’ Benjamin began his story rather slowly, but then the drama of Runner Bean’s disappearance got the better of him and he poured it all out in a tearful rush.

‘I can’t believe it.’ Fidelio sat back. ‘Charlie’s never taken a dog with him before. I didn’t know he could.’

‘He didn’t take him,’ wailed Benjamin. ‘Runner Bean vanished long after Charlie went in. At least I think so. But Charlie’s never gone right into anything, has he? He always stays outside. It’s only his mind that goes in.’

‘Until now,’ Fidelio remarked. ‘Perhaps his endowment is developing.’

Benjamin shook his head. ‘Something’s wrong, Fido.’ He got up and walked over to a window that overlooked the square. ‘My stalkers have gone. I think I’ll take a chance and run up to the bookshop. Charlie’s uncle will know what to do.’

‘Has he . . . has he . . . has he . . . popped the question?’ sang Mrs Gunn.

‘Pardon?’ said Benjamin.

‘Uncle Paton, Mr Yewbeam,’ Mrs Gunn dropped her musical tone temporarily. ‘He’s surely going to make an honest woman of Miss Ingledew. How can he resist? He really ought to marry her. The whole city is waiting.’

‘You mean you’re waiting, Mum,’ said Fidelio. He turned to Benjamin. ‘I’ll come with you, Ben. Don’t like to think of you alone in this city without your dog.’

‘I am eleven,’ sighed Benjamin.

‘And I’m twelve,’ said Fidelio firmly. ‘There’s a difference.’

After weeks of dark skies and frosty winds, today a few rays of frail sunshine had begun to filter into the city. They did nothing to lift Ben’s spirits. He felt quite resentful towards Charlie for doing something so risky. But that was Charlie all over. He was always rushing into situations without thinking them through.

Fidelio, who seemed to have read Benjamin’s mind, said, ‘It’s possible that Charlie never meant to go into that painting. He might have been sucked in, against his will, just like your dog.’

‘Hm,’ Benjamin grunted.

The boys were now entering the narrow cobbled street that led to the cathedral. On either side of them, half-timbered houses with ancient crooked roofs leaned over the cobbles at dangerous angles. The bookshop stood directly opposite the great domed cathedral; a sign above the door read Ingledews in olde worlde script and, in the window, two large leatherbound books were displayed against a curtain of dark red velvet. Miss Ingledew sold rare and precious books.

If the boys had paid attention to the gleaming black car that stood outside the shop, they might have had second thoughts, but they were in such a hurry they rushed straight in. A small bell, attached to the inside of the door, tinkled pleasantly as they entered the shop. The sight that met their eyes, however, was not at all pleasant.

Sitting in a wheelchair beside the counter was Mr Ezekiel Bloor, the owner of Bloor’s Academy. Mr Ezekiel, as he liked to be called, was a hundred and one years old and his head was as close a thing to a living skull as you’re ever likely to see. He was covered in a tartan blanket and wore a red woollen hat pulled well down over his large wrinkled ears. There was very little flesh covering his large nose with its high knobbly ridge, or the sharp cheekbones and long chin. Mr Ezekiel’s eyes, however, were another matter. They glittered beneath the protruding forehead as black and lively as the eyes of a ten-year-old.

Behind the ancient man’s wheelchair stood a burly, bald-headed man: Mr Weedon was the school porter, chauffeur, handyman and gardener. There was nothing he would not have done for Mr Ezekiel, including murder.

Fidelio and Benjamin would gladly have stepped backwards out of the door, but it was too late to escape. They reluctantly descended the three steps into the shop.

‘Aha!’ croaked Ezekiel. ‘What have we here? Odd customers for a rare book, I’d say. I bet you haven’t got a hundred pounds to spare, Fidelio Gunn, not coming from a family of eight. You can’t even afford a pair of shoes, I’d say.’ He directed his mocking gaze at Fidelio’s shabby trainers.

Fidelio shifted his feet self-consciously, but he was not the sort to be outdone, even by the owner of Bloor’s Academy. ‘I save my best for school, sir,’ he said, ‘and we’ve come to see Emma Tolly.’

‘Girlfriend, is she?’ snorted Ezekiel. ‘The little bird?’

‘Not at all, sir,’ Fidelio said calmly. ‘She’s a friend.’

‘And who’s the scrawny lad trying to hide in your shadow?’ Mr Ezekiel twisted his head to see Benjamin, who was, indeed, trying to hide behind Fidelio. ‘Who are you, boy? Speak up!’

Benjamin was now in quite a state; desperate to get help for Runner Bean, he could scarcely concentrate on anything else, yet he knew he couldn’t mention his dog’s disappearance to Mr Ezekiel.

‘Come on, you half-wit!’ spat the old man.

Fidelio said, ‘He’s Benjamin Brown, sir. Charlie’s friend.’

Mr Weedon decided to enter the conversation. ‘So where’s Charlie Bone today?’ he asked, with a sneer.

Benjamin croaked, ‘Busy.’

Mr Ezekiel gave a nasty chuckle. ‘I know who you are. Your parents are private detectives. Hopeless sleuths. Where’s your dog, Benjamin Brown?’

Benjamin screwed up his face, gritted his teeth and sent Fidelio a helpless look of despair. ‘E – rr . . .’

Fidelio came to his rescue. ‘He’s at the vet. Benjamin’s very upset.’

Mr Ezekiel threw back his head and cackled lustily. Weedon joined in with a deep chortle, while the boys watched them in baffled silence. What was so funny about a dog being at the vet?

The curtains behind the counter parted and an elegant woman with chestnut hair appeared. She was carrying a heavy gold-tooled book, which she laid very carefully on the counter. ‘Hello, boys. I didn’t know you were here,’ said Miss Ingledew.

‘They’re after your little bird,’ Mr Ezekiel sniggered.

Miss Ingledew ignored his remark. ‘I think this might be what you want, Mr Bloor,’ she said, turning the book so that he could see its title.

‘How much?’ snapped the old man.

‘Three hundred pounds,’ Miss Ingledew told him.

‘Three hundred.’ Mr Ezekiel slammed a mottled hand on to the valuable book, causing Miss Ingledew to wince. ‘I only want to know a bit about marquetry. Mother-of-pearl inlaid boxes in particular, dates and sizes, et cetera.’ He began to flip the pages over with his long, bony fingers. ‘Help me, Weedon.’

While the old man was occupied with the book, the two boys moved swiftly across the shop and round the counter. Mr Ezekiel began to whine about the small print as they stepped through the curtains and entered Miss Ingledew’s back room.

Here, there were even more books than in the shop itself. They covered the walls from floor to ceiling: old, faded, mellow books; large on the bottom shelves and very small at the top. They gave the room a musty, leathery smell that was rather comforting. But it was, after all, a sitting room, so there were several small tables, a sofa, two armchairs, an upright leather chair and a desk. Hunched over the desk was a black-haired man who, even sitting down, seemed exceptionally tall.

The man paid no attention to the boys but continued to pore over the papers in front of him.

Fidelio cleared his throat.

Without looking up, the man said, ‘If you want Emma and Olivia, they’ve gone to the Pets’ Café.’

‘Actually, Mr Yewbeam, it’s you we wanted,’ said Fidelio.

‘Ah,’ said Charlie’s uncle. ‘Well, I’m busy.’

‘This is urgent,’ Benjamin blurted out. ‘Charlie’s gone into a painting, and so’s my dog, and they won’t come out.’

‘They will.’ Uncle Paton continued to scrutinise the papers. ‘Eventually.’

‘You don’t understand,’ said Fidelio in as urgent a tone as he could muster. ‘This time Charlie’s gone right in – he’s disappeared – vanished.’

Uncle Paton raised his eyes to peer at them over the top of his half-moon spectacles. ‘Vanished?’

‘Yes, Mr Yewbeam. Completely gone,’ said Benjamin, on the edge of tears. ‘There was this painting in your cellar, and Charlie’s grandma, the nice one, asked me to go down and help because Charlie had disappeared. So I went down and Runner Bean followed me, and then he . . . went in, too.’

Uncle Paton frowned. ‘What sort of painting was this, Benjamin?’

‘Horrible,’ said Benjamin. ‘Lots of dark towers and mountains. It had a name at the bottom. Badlock, I think it was.’

‘Badlock!’ Uncle Paton sprang up so rapidly his chair fell over and all the paper fluttered off the desk.

‘Is it a dangerous place?’ Benjamin asked breathlessly.

‘The worst place in the world,’ said Uncle Paton. ‘Though I can’t be certain that it was ever actually in this world.’

Benjamin’s mouth fell open. He gaped at Paton Yewbeam, trying to make sense of what he had said. Even Fidelio was lost for words.

‘No time to lose. Come on, boys.’ Uncle Paton brushed aside the curtain and marched into the shop, quickly followed by Fidelio and Benjamin.

Squirra stew

Julia Ingledew was anxiously watching Ezekiel Bloor as he thumbed through her precious book. She didn’t like to wrest it away from him in case even more damage was done. When he saw Paton Yewbeam, however, the old man looked up.

‘Aha! Paton Yewbeam!’ Ezekiel declared. ‘Thought you didn’t go out in daylight.’

‘I go out when I please,’ Uncle Paton retorted, snatching his fedora from a hat stand in the corner.

‘Hm,’ sniffed the old man as Paton strode to the door. ‘I suppose that’s why this oldey worldey shoppey is so dark. You could do with a bit of electricity in here, Mrs Books.’

Uncle Paton stopped mid-stride, causing Benjamin to walk straight into him. ‘Watch your tongue, Ezekiel Bloor,’ growled Paton.

‘Or else . . .?’ sneered Ezekiel. ‘I hope you’re not thinking of asking this good lady to marry you, Paton. She’d never have you, you know.’ He broke into a fit of cackling.

The boys watched uneasily as both Miss Ingledew and Paton Yewbeam turned very pink. Ezekiel had let go of the book to wipe his mouth and Miss Ingledew took the opportunity to slide the rare book away from him. Mr Weedon pulled it back again.

Recovering his composure, Paton said, ‘Kindly keep your nose out of my business, Mr Bloor.’

‘And you run along about yours.’ Ezekiel waved his wet hand dismissively.

Paton hovered, glaring at the old man. ‘I hope you’re not damaging a rare book.’ He looked at Miss Ingledew. ‘Ju . . . Miss Ingledew, do you want me to . . .?’

‘No, no,’ said Miss Ingledew, still very pink. ‘You go, Pa . . . Mr Yewbeam. I can see it’s urgent.’

‘It is rather.’ Paton was now in an agony of indecision. He clearly wanted to stay and protect Miss Ingledew, but Benjamin was already halfway up the steps, and tugging at his sleeve.

‘I’ll ring you,’ Miss Ingledew picked up her mobile, ‘if anything goes wrong.’

‘You do that.’ Paton gave her a meaningful look and stepped through the door that Benjamin was impatiently holding open.

‘What are you going to do, Mr Yewbeam?’ asked Fidelio, as they sped down the street.

‘It depends what is called for,’ said Paton.

‘Look!’ Benjamin pointed down the street.

Running towards them were two girls: Emma Tolly, in a blue anorak with her blonde hair flying over her face, was struggling with a large basket, while beside her, Olivia Vertigo also carried a basket, this one smaller and obviously easier to hold. Olivia looked quite spectacular in an outsized sweater with STAR picked out in gold sequins on the front. She also wore a sparkly white hat and a gold scarf. Her hair was a deep purple.

‘Mr Yewbeam,’ called Olivia. ‘You’ve got to help.’

‘Please, please, please,’ cried Emma. ‘Something awful has happened.’

The two parties met in the middle of the street.

‘We’re extremely busy, girls.’ Uncle Paton brushed past them and continued on his way.

‘What’s your awful happening?’ asked Benjamin, stopping in spite of himself.

‘The Pets’ Café has been closed,’ wailed Emma. ‘Permanently. It’s awful. We could see Mr Onimous sitting at a table. His head was in his hands. He looked so depressed.’

‘We can deal with that later, Em.’ Fidelio stepped round the girls. ‘Something worse has happened to Charlie.’

‘And Runner Bean,’ Benjamin added. ‘They’ve both gone. Vanished. Utterly disappeared into a painting.’

Emma lowered her basket, from which a loud quacking could be heard. ‘What are you going to do?’

‘We won’t know till we get to Charlie’s house,’ said Fidelio, anxiously watching the departing figure of Uncle Paton.

‘We’ll come!’ Olivia was never one to be left out of things. ‘Let’s leave our pets at the bookshop, Em.’

‘Wouldn’t go in the shop if I were you,’ Fidelio called over his shoulder. ‘Old Mr Bloor is there.’