Полная версия

Facing the Lion

Quickly she put her hand in my pocket and pulled out a five-franc piece.

“And what is this?”

“I took it, but I did not steal!”

“Can you explain that?”

“Yes! I just had to correct the Christchild’s terrible injustice to Frida. I wanted to buy the doll for her.”

To my surprise, Mum bought the doll and put it on my shelf next to my bank from Mrs. Koch.

“Girl, stealing is taking something that is not yours, no matter what you do with it. This doll is going to remind you. It will stay there. Don’t dare take it away. As long as you leave it there and do not steal again, I won’t tell Dad. You know, he had to work many hours, yes, days to earn five francs. It is going to be our secret between us two. You know how your father stands for honesty. You watch it. He has never spanked you before, but for sure he will. Never remove that doll from there if you don’t want to have a problem!”

Thursdays, we had no school and sometimes my cousin Angele would come over with her doll while I was holding class with my doll, Claudine. I took it all very seriously, repeating Mademoiselle’s civic lessons. But I had trouble explaining to the dolls the idea of conscience. I didn’t understand what it was, how it worked, how a person could lose it, or even be without one in the first place.

So one day I asked Dad, “What is a conscience?”

“It is a voice inside you that tells you what is good or what is bad.”

“Dad, my teacher said that each evening we should think about our day and what we have done.”

“This,” Dad said, “is called the examination of one’s conscience. As you grow, you’ll be able to do that. Little ones can’t do it yet.”

“I don’t hear anything. Every evening I listen. No one inside me talks. Where can I find it?” I did not want to be a “little one” anymore.

“Continue searching and listening. One day it will come. It is in you.”

“Daddy, last night in bed my legs talked!”

“What did they tell you?”

“That they wanted to turn.”

“And how did you answer?”

“I changed position.”

“Those are your muscles. But, someday, the same feeling will pop up in your thoughts, and you’ll have to listen to them and do what they tell you.”

Teaching Claudine was a serious matter to me. I was sitting in my “classroom” one day, watching Mum sew. When Dad stepped in, I was happy—until I saw his gaze fall on the little doll sitting on the shelf. I felt like Zita who, when she had done something bad, crawled under the bed!

“Where did that doll come from?”

I knew I was in trouble.

“Isn’t it cute? It is Simone’s taste,” Mum answered without taking her eyes off her work. I got stiff and ducked out of Father’s sight.

“It must have been expensive, because a miniature is always very expensive!” I was doomed! I stared at Mother. She continued sewing.

“By the way, Adolphe, talking about being expensive, did you check on the price of a new bicycle?”

“Yes I did. We can’t afford it. It’s much too expensive.”

“How long do we have to save?”

My dear mother had kept our secret. What a relief! That evening in bed, I looked at the doll and thought of my cookie and chocolate distribution; I remembered the happy faces of my classmates. Then my heart started pounding. All that money I had taken could have bought a bicycle for Dad. My heart was beating even faster. Was that my “conscience?” How could I know? I couldn’t ask Dad without giving away our secret. It was a painful situation!

The next morning, I pushed the doll out of my sight. I did so every day for days. But every evening it was back in its place. Each day my heart beat more wildly. I trembled in the morning when I would hide the little doll away on the shelf. One day I just couldn’t do it anymore. My mother’s presence became unbearable; her silence a load. I had become conscious of my conscience!

Back in the classroom, a breathtaking vision unfolded before us as Mademoiselle vividly described God’s throne. Full of enthusiasm, she spoke about the angels that God had specially created. Playing divine music on golden harps, they surrounded his throne. I yearned to be there.

“Men cannot see them because they are spirits. We cannot see spirits. They have big wings and fly through the heavens.”

After that inspiring talk, I had a hard time concentrating on arithmetic. After two hours of class work, the priest came for our religious lesson, the catechism.

He entered class at 11 a.m.

“Blessed is the one that cometh in the name of God,” he said in a ceremonial voice.

The class stood up and said, “Amen.”

“How can we get into heaven?” he asked.

That was just what I wanted to know.

“The best way is to suffer,” he answered. “Each time a person suffers, he gets chastised by God, and God chastises everyone whom he loves. So be happy and rejoice when you suffer.”

After class I went up to the priest. “My Father, why did God create angels right away in heaven while we have to suffer to get there?”

The face of the priest became menacing, his eyes fiery. With a trembling voice, he said loudly, “You are just six years old, and you dare judge God?”

“My Father, I just...”

“Shut up! You have a rebellious spirit; you are on the way to hell if you continue like that! Learn your lesson and never question it!”

I walked away slowly. I was crushed. I thought, I’m so ashamed of myself. I won’t tell Mum about my religion class today. It will make her feel bad. The thought made me cry. From then on, I never felt at ease in my catechism classes. The priest’s dark eyes and threatening voice upset me. It seemed he only knew how to talk about hell. I preferred to go to church.

FEBRUARY 1937

On Sundays, we walked down the street dressed in our best clothes. Mother had a nice hat. Dad always wore a smart beret that he touched with his right hand when people would greet him. I held on to Dad’s left hand and held my pearly covered missal in the other hand. Mother clutched her purse and her missal tightly to her chest. She greeted everyone with a nod and a smile.

“It must be ten o’clock. The Arnolds are on the way to church,” some of our neighbors said. I was very proud to see how people greeted my parents courteously.

Our church was impressive. The door was wide open. The sun’s rays came through the high windows, illuminating the golden altar and making the light from the candles almost invisible. But it was not quite the same anymore. I looked at the images. They all had dramatic faces. I could no longer look at the priest and his assistant during the Eucharist, but I kept beating my chest like everyone else while repeating, “It’s my fault, my fault, my fault only.”

It was a nice warm February day. After church, we went on an outing. “Leave Claudine home. You can’t take her along. We’ll be hiking through fields and meadows.”

As far as our eyes could see, the brown earth stretched out; some meadows were turning green.

A stork, the state bird of Alsace, walked in the swamp beside the Doller River. Zita, with her tail wagging, ran back and forth across the meadow, chasing everything in sight and playing hide-and-seek with me. The rays of the setting sun danced between layers of mist that hovered just above the grass. Suddenly in the distance, I spotted a man and a young boy crawling out from underneath the thicket. They hurried off and quickly disappeared from view.

That Sunday evening before going to bed, Mum sat down to talk with me. I felt uneasy.

She looked at me tenderly but seriously with her deep blue eyes. “I know you go to church every morning to pray before going to school, but Dad and I ask you never go to church without us!”

Her words felt like a slap! “But why, Mum?”

“The church is a very large place, and there is not much light. A bad person may hide himself and then attack you.” Taking my chin in her hand she repeated in an undertone, “Never go to church for prayer by yourself, all right?”

On Monday morning, I passed by the church. My heart was pounding. I obeyed my parents’ order, but I wasn’t happy about it. At school, we had the usual Monday routine, the story of Saint Theresa de Lisieux, the review of our homework (I had the best marks again and Mademoiselle’s compliments), and Frida was there. But now she had to sit in the last row all by herself because of her cough. The sky turned brownish gray and snow had started to fall. We had to turn the lights on again. By the time the morning class was over, a snow storm was in full force. We had to walk backward alongside the houses. Frida had a hard time fighting against the wild wind. She coughed constantly, gasping for breath.

“I didn’t go to church, Mum!” I whispered in her ear as I kissed her.

“I know you are an obedient girl.” Mum brushed the snow off and brought me nice warm slippers, and I told her about the struggle we had to get home.

“And you know, poor Frida has to sit in the last row in class, all alone by herself because she coughs.”

“When she coughs, turn your head away from her!”

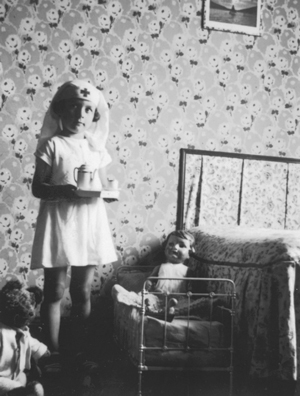

In the afternoon, the sky got brighter. Frida was absent from school again. The empty bench in the back of the class brought home to me what sickness could do. I decided that before becoming a saint, I would first become a nurse.

Sitting in the class, I could see the sparrows across the way, perched on the ledge of the church window. I imagined the rays of sunshine passing through the stained glass, illuminating the altar. But I couldn’t go in.

Under my covers, I fumed against my parents. I tried to get Dad to give me permission to go to church. “What did your mother tell you?” And, of course, he backed her up.

Why did my parents always stand up together against me? When Mum said something, Dad stuck by her. If I asked Mum about something, she’d say, “Did you talk to Dad? If not, we will do it together!” There seemed to be no way around it. I just couldn’t sleep.

My parents were sitting in the salon as they did every evening, Father reading aloud, Mother knitting. But now they were both talking. Maybe about me—I thought for sure it was about me. I got up to listen, but my heartbeat was so loud that I went back to try to listen from my bed.

They were talking about religion. It was hard to follow; often their voices disappeared. “Adolphe, it is unacceptable, impossible that God is willing to come down in a Host that is elevated by such dirty hands as the priest’s.”

“Emma, we humans have no right to judge God and...”

This conversation was hard to understand. I covered myself up again. But I wondered about the priest who didn’t know that he had to wash his hands before he said the Mass!

I stood by the side door of the church. My heart raced. “This is the house of God. There can’t be a danger in there, can there?” I opened the door. The church was empty and gloomy. I quickly closed the door and left! By the following day, I had made up my mind. I would take the holy water and quickly make the sign of the cross, walking on my tiptoes and crouching down to hide behind the church pews. In front of the altar, I would quickly kneel and apologize that I could not stay, because I was not allowed to stay in the church alone. I would cross through and go out on the other side.

My jumping heart almost stopped me. The door made a grinding noise. I shook all over. The faces of the saints seemed to move. In front of the altar, I was breathless. By the time I got to the other side, my legs vanished. I thought I heard a voice in the nave. I ran out the side door as fast as I could and slammed the door behind me.

My conscience had been in turmoil over whether or not I should again visit the church alone. I came to a decision. “God is above my parents, and they don’t know my goal—I want to be a saint.” It was my great secret. I was ready to pay the price and face my parents’ disapproval. It never came to that because they never found out about my secret visits.

I had been consecrated to the Virgin Mary since my baptism and was to be present at the procession. The priest would walk under a canopy carried by four men. He would hold a golden image of the sun upon his face, and the girls would throw rose petals in the air in front of him. What a sacred service that was! Mother made me a white organdy dress with a light blue belt. She bought some new shoes and a rose crown for my head. I couldn’t wait! But then, suddenly, a bad cough canceled everything. I had never been sick; why did I have to come down with a bad cough? Was God mad at me? Mother gave my special outfit to another girl! I burned with jealousy! Three days later I felt well enough to go out again. That made me feel even worse.

When I went back to school, Frida was still absent. The doctor said she couldn’t come to school until her cough cleared up. Each day, I would call out to her, and each day her house remained silent.

Passing by her little house, I saw pots of beautiful white flowers in the backyard. Finally someone had given Frida a little attention.

Mum sent me to Aline’s shop to buy some sugar for our strawberries. I climbed up the four steps into the grocery store and stood behind a lady wearing crocodile shoes. She was tall and wore a summer overcoat—a true lady, so different from the women on our street.

As I saw her left hand in a lace glove, I was breathless. Here she was—the beautiful lady that I so admired! I must have stared with my mouth open. Good thing Mother didn’t see me.

Aline whispered, “Simone, don’t gape like that. The lady has eaten too many cherries and drunk water.” What a disappointment! Didn’t that fine lady know any better? I hadn’t noticed her big belly before. I saw only her nice blouse with that beautiful necklace, but now I realized that her stomach was so big she might burst at any moment. I stepped aside, running away as soon as I got my purchase, leaving that stupid lady behind!

“Simone, why didn’t you take Zita along to the store?” Mum asked.

“Zita is sick, and so is Claudine.” I was a nurse and Mother had made a special outfit for me. Mother said, “But this is only make-believe. You still can take Zita out. She needs it.”

“I’ll dress her and put her in Claudine’s carriage because she’s sick!” Mother laughed. She knew that I loved to dress my doggy, put her on her back like a baby, and surprise passersby with her.

“But now Zita badly needs to be on her four legs.”

“But Mum, she is really sick!” I was the nurse. I knew better than Mum.

“How do you know?”

“Can’t you see that every day her head gets smaller?”

Mother had put the sugar on the strawberries. “You see, all the juice will come out and dissolve the sugar. We will cook it when we come back from the garden.”

We had a nice view from the garden. On the horizon on one side of the hill, we could see the blue line of the Vosges Mountains; on the other side, the Schwarzwald Mountains, and a bright sun too!

“Keep an eye on Zita. She loves to make holes in the ground.” This wasn’t an easy job. When Zita smelled a mouse, she was determined, and she was strong too. I had a hard time pulling her out by her back legs.

Suddenly, night climbed up behind the trees. We gathered up the garden tools quickly. I had tied Zita on her leash for the walk back home. We heard noises like the wind and saw a fire-red sky. A dark cloud raced over our heads. Mother took me by the hand. We had to run for cover to keep from being harmed by the “fireworks.” A farm was ablaze!

Fiery sprays jumped out of the huge flames, sparking little fires in the dry grass. We saw chickens running all over the place; some were already on fire. The cows and the pigs couldn’t be saved. All the fire engines from the city arrived and sprayed water out of long hoses to wet down the farmhouse and the neighbors’ homes. The firemen’s helmets reflected the flames, their faces were red, their clothes dark. A terrible crash rekindled the fire, and the desperate cries of all the animals inside were silenced.

When we were permitted to pass by, the charred beams were still smoldering. The air was heavy with smoke for a long time.

I came home freezing. I couldn’t eat or play. Mother suggested I go to bed because I had a fever. Zita, too, was all upset and lay down next to my bed with wet eyes. It wasn’t bedtime yet, but Mother said, “Get a good night’s rest and you’ll feel better.”

But the night wasn’t “good.” I saw fire everywhere even when my eyes were closed. In my dreams I heard the terrible cries of the burning animals. Mother decided to sleep with me.

The next day was no better. “Mum, did Lucifer burn the barn and the animals in it?”

Mother named all the different ways that fires could start, but it didn’t take away my fear of hellfire. Dad tried to distract me by encouraging me to do some painting, but I was too restless.

Even though the weather was nice and warm, Frida was missing from school again. “Mademoiselle, why can’t Frida come to school?” Instead of answering she caressed my hair.

“Is she still coughing?”

“Oh, no, she’s not coughing anymore. She’s in heaven now.”

“That’s why.”

“Why what?”

“I saw the pots of white flowers.”

Passing in front of her modest home with the shutters closed, I started to cry. The flowers were withered. They too had died. I just couldn’t look at the house anymore. My sadness about her departure for heaven made me cross the street. Yet I was relieved for her. She didn’t cough anymore but would play harps sitting on a cloud. Could she see me?

Catechism class—what would the priest talk about today? “It is necessary to make a distinction between hell and purgatory. When a person dies and has committed sins, that person can avoid burning eternally in hell if he takes the last Sacrament. One has to call for a priest, the person has to confess all his sins without omission, and afterward he can eat the Communion. Maybe he cannot go to heaven right away, but instead will have to go to purgatory. It is a sort of an antechamber of hell. People suffer and burn, but they can get out after their sins have been purged. This time can be shortened if the family asks the priest to say Masses. The family has to make sacrifices and prayers for the dead.”

The night was terrible. I saw Frida in the flames, the lady with her burst tummy moaning. The firemen had tails like the Devil, their faces were fire-red, and the twins were drowning in a river of fire. The saints didn’t hear my prayers because of the roaring fire. I screamed and woke up. Mother was sitting on the edge of my bed, wiping the sweat off my forehead. My bed was a snarled mess of covers. Mum tucked me in again and kissed me. I fell asleep, but a similar dream haunted me. The following evening I didn’t want to go to bed. My bed had become hell.

Zita’s head went back to normal again. She had given birth to puppies! Soon after, on one sunny day, my fancy lady passed by pushing a baby carriage. She, too, had shrunk. Running to Mum I asked her, “Do mothers carry their babies in their tummies like Zita?” Mother’s answer made liars out of Mrs. Huber and Aline!

“But why do people say I should put sugar for the stork in order to get a sister?”

“That’s a story for little ones!”

Again, for little ones! I’m not a little one. “Why, Mum, why do adults lie?” I got no answer.

“Didn’t God say ‘You shall not lie?’ Aren’t they afraid to go to hell?”

That night, while under my covers, I decided to avoid Mrs. Huber. I was not going to talk to her anymore. But why didn’t Mother answer my question? Why do grown-ups lie to children? I would have to beware of them! That put me in a very bad mood.

Dad was a wonderful playmate—always encouraging me to try new things. I had some trouble with the spinning top Uncle Germain had made for me. It turned, slowed down, wobbled, and fell motionless. To get it started again I had to wind the string around it, put the point on a level place, and swiftly jerk the string to liberate it.

“Keep trying. You’ll do better next time,” Dad said from the balcony, where he stood watching me. No cars came down our block; I had the whole street to myself. Some of our neighbors, who spent their summer evenings leaning on cushions and looking out the window, kept on teasing me. They made me even more determined. But it was time for me to go to bed, even though the sun had not yet set. It was so hot that Mum had decided not to close my shutters completely.

“Mum! Dad! Hurry, help, help! There is fire everywhere!” A strong orange-red light had enveloped my room. Dad took me from my bed and brought me to the balcony. Mrs. Huber, Mrs. Beringer, Mrs. Eguemann—everyone had come outside to look at the spectacular light show. The sun had set, the blue line of the mountain had turned black, the sky was fire red, and, downstairs, our teenage neighbor John played the blues on his mandolin.

“Who opened the door to hell?”

“This is not hellfire. It’s a spectacular sunset!”

“But only a giant fire could send so much red light into the sky!”

Mum and Dad looked at each other and shook their heads.

“I know for sure it’s hell because the priest said that a person either goes down to hell or up to heaven,” I insisted.

Dad explained something about fire and lava inside the earth, convincing me about hell even more and making me even more terrified. Mother brought me back to bed. Sitting with me, she told me once more that it wasn’t hell; it was the sun.

“Don’t be so scared about hell. We have the saints to pray for us, and we have a guardian angel.”

It didn’t help because I knew how terrible it is to die unprepared.

How awful, how terrible if my parents would die during the night! Every night I would sneak into their bedroom and put my finger under their noses to find out if they were breathing. Only then could I go to sleep!

One Sunday, as usual, the three of us went for our afternoon walk. It brought us near a tavern with a garden. I remembered being there when I was about three years old. I had danced on a tabletop and the customers had applauded. Dad recalled my performance, too, and he said sternly, “Remember this place? Let it be said, I do not want you to become a show girl!”

Really! It wasn’t necessary for him to remind me. I was now a serious girl—nearly seven years old! I know about sickness, death, purgatory, hell, and God sending all kinds of situations to test us. My parents tried to cheer me up, but my innocent childhood free of sorrow was gone. My religious education at school taught me how painful life on this earth can be and what effort one has to go through to become a saint. That had become my chief concern.

One year of intense religious instruction had propelled me into a state of permanent fear, fear of God—the Father who was so severe, so exacting. I really had no desire to dance—how could I?

Sitting on a little footstool, I was holding class for Claudine, trying to teach her the pronunciation of the German alphabet. Mother was waxing the shared wooden stairs outside our apartment; it was her turn to clean them. She was always unhappy because our neighbor only used water to wash them down, while Mum believed in shiny wooden steps. I heard her talking to someone in the hallway; suddenly she came in to get something and went back out.