Полная версия

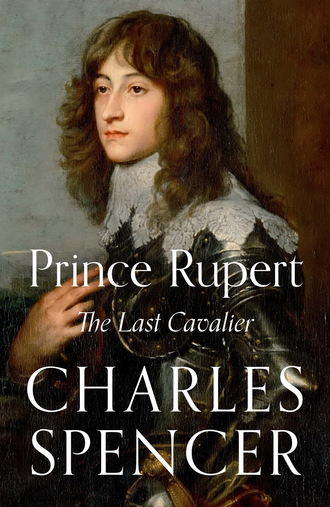

Prince Rupert

Charles went first to Hampton Court, then to Windsor. To raise funds, he sold Windsor Castle’s silver plate. In February, afraid that fighting was about to erupt, Charles took Henrietta Maria and the young princesses to Dover. Here the royal party met Prince Rupert, who had come to thank his uncle for his part in securing his release from prison. Although Charles was delighted to see Rupert again, he spent time closeted with the prince, explaining that it would be best if he returned to the Continent: there was still a hope of peace in England, but this would be diminished if the king was seen to have enlisted his warrior nephew. Rupert understood, and accompanied the queen and her daughter Mary to Holland, where the princess was to marry the Prince of Orange. Henrietta Maria took with her some of the Crown Jewels, which she intended to sell. She would invest the proceeds in forces and weapons, to aid her beleaguered husband. Meanwhile, Charles headed for Greenwich for talks with Parliament. The dialogue was bitter and brief.

The king now made for York, keen to put distance between himself and his antagonists, and eager to seize arms that had been stockpiled in Hull since the Bishops’ Wars: after the Tower of London, Hull was ‘the chief magazine in the kingdom for arms and ammunition’.[fn5] However, Sir John Hotham, recently appointed Hull’s garrison commander by Parliament, denied access to his king. Hotham flooded the surrounding fields with water from the Humber and promised to sacrifice his life, rather than surrender the town.

More important men than Hotham now declared against the king. Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, was the 50-year-old son of the dashing Elizabethan courtier who had plunged from favouritism to armed rebellion and paid for his treachery with his life. James I had refused to visit the sins of the father on the son, and allowed Robert to revive the title and repossess the estates that his father had forfeited. Ironically, given his later clashes with Princes Rupert and Maurice, as a younger man Essex had fought against the Hasburgs for the restoration of the Palatinate.

Essex had spent much of the 1630s quietly enjoying his wealth and estates. A brief stint commanding a coastal naval squadron was followed by service as a lieutenant general in the First Bishops’ War. The dispiriting campaign had been followed by a disappointing treaty that Charles I had insisted on brokering himself. The king then further alienated Essex, by failing to thank or reward the earl for his efforts. In January 1642, Charles tipped Essex irretrievably into the arms of Parliament. Egged on by the meddlesome Henrietta Maria, and ignoring the advice of his wisest councillors, Charles asked the earl to resign as Lord Chamberlain of the King’s Household. Six months later Essex accepted his appointment as Lord General of the Parliamentary army. The royal couple had handed their enemies a cautious but competent commander.

*

Both sides in the Civil War claimed to be fighting for the king: it was the definition of kingship that separated them. For most Royalists, the thought of armed conflict against God’s anointed was anathema — an aberration that challenged the cornerstone of their hierarchical beliefs. They saw matters as clearly and simply as Sir Francis Bacon, the Solicitor-General: ‘Where a man doth levy war against the King in the Realm, it is Treason. Where a man is adherent to the King’s enemies, giving them aid and comfort, it is Treason.’[fn6] The Prince of Wales’s chaplain echoed this sweeping condemnation of the Crown’s opponents: ‘Rebellion is a sin that strikes at God’s own self, at the face of Majesty: there is no such express image of God in the world as a King is; every Christian is the Image of Christ as a man, every Minister of the Gospel is (or ought to be) the Image of Christ as Mediator, but a King is the Image of Christ as God, and to rebel against a King is to strike at the face of Christ as God; which was more than they that crucified him durst to do.’[fn7]

The Parliamentarians justified their armed opposition by making a delicate but precise distinction between the king as ruler, and the king as a man. It was quite possible, they believed, to support the king while attacking the evil advisers who were leading him astray. In July 1642, court critics in both Houses joined in a powerful declaration: ‘It cannot be unknown to the World, how powerful and active the wicked councillors about his Majesty have been, both before and since this Parliament, in seeking to destroy and extinguish the true Protestant Religion, the liberty, and Laws of the Kingdom …’[fn8] This subtle separation of loyalties was a common defence throughout Europe at this time and had been employed by rebels in England since the Middle Ages, when justifying resistance to absolute rule. Some critics of the king took their strand of logic past breaking point, openly calling the Royalists ‘rebels’. Parliamentarians looked with disdain on those who offered unquestioning loyalty to the Crown: ‘We found’, a Parliamentarian wrote, when looking back on the start of the war, ‘that the common people addicted to the King’s service have come out of blind Wales, and other dark corners of the Land; but the more knowing are apt to contradict and question, and will not easily be brought to the bent.’[fn9]

The political certainty of both factions was fuelled by strong spiritual allegiances. Continental Europe gave compelling lessons in the importance of binding religious prejudices tight to military ambition. Contemporaries recognised the power of the blend: watching the fighting effectiveness of Gustavus Adolphus’s troops, a British Protestant observed: ‘It is not without a mystery, I suppose, that the old Israelites had an Armoury in their Temple: they would show us, that these two cannot well be parted. And truly, methinks, that a Temple in an Army, is none of the weakest parts of fortification.’[fn10] As the king and Parliament prepared for war, each claimed God’s support.

If religion had been the sole consideration, the prince could have chosen to side with the Parliamentarians, as did his elder brother Charles Louis. Rupert’s Calvinism was in tune with their Puritanism and his family had long benefited from parliamentary support for the Palatine restoration. However, his first loyalties were to the uncle he loved and to the basic principles of royal rule. Charles had been the generous patron of Rupert’s family during its protracted exile, reassuring them of his best intentions even when failing to deliver much of substance. Meanwhile, the king helped to fund his impoverished relations — Rupert received an annual royal pension of £300 — and poured love on his sister and her hapless brood, after Frederick V’s death. He wrote to Elizabeth of Bohemia in 1634:

My Only Dear Sister,

… I could not let this honest servant of yours go without these lines, to assure you of the impossibility of the least diminution of my love to you; the which, as I am certain you easily believe, so I desire you to be assured, that all my actions have and shall tend to your service; and that the counsels and resolutions that come from me, is and will prove, more for your good, than those of any body else: and so I rest

Your loving brother,

To serve you,

Charles R.[fn11]

It was now time to repay the family debt and Rupert did not hesitate in accepting Henrietta Maria’s invitation, in August 1642, to cross once more to England, in support of King Charles. The prince made public his feeling of obligation to the king: ‘And what a gracious supporter hath he been in particular to the Queen of Bohemia (my virtuous Royal mother) and to the Prince Elector, my Royal brother, no man can be ignorant of: if therefore in common gratitude I do my utmost in defence of His Majesty, and that Cause whereof he hath hitherto been so great and happy a patron; no ingenuous man but must think it most reasonable.’ Rupert stressed the high regard in which Europe held his uncle, judging him ‘the most faithful and best defender of the Protestant Religion of any Christian Prince in Europe, and is so accounted by all the Princes in Christendom.’

Rupert also countered those who painted him as a foreign mercenary, eager to ply his warrior trade whatever the cost to the native population: ‘I would to God all Englishmen were at union amongst themselves, then with what alacrity would I venture my life to serve this Kingdom against those cruel Popish Rebels in Ireland.’[fn12] This last point was in response to enemy claims that Rupert and his men were secretly fighting for Catholicism.

In the same defence against his tormentors, Rupert revealed his views on the correct relationship between a monarch and his subjects. It was an uncompromising creed: ‘Suppose that he [Charles] had swayed his Sceptre with a strict hand, reining in the bridle of Authority with harsh Taxation and Tyranny (which it is too well known he did ever abhor as infections to his Sacred Person) yet I say were it so, the Subjects are not thereupon to withdraw their Obedience and Duty neither by the Laws of God nor the Laws of Man, for they are however or at leastwise should be still his Subjects …’[fn13] Such sentiments were succinct, traditional, and unburdened by profound analysis.

*

Rupert’s first attempt to reach England failed. He set off across the North Sea on a 42-gun ship, the Lyon, with his brother Maurice. Accompanying them were Rupert’s chief engineer, Bernard de Gomme, a Walloon; and his favourite explosives’ expert, Bartholomew de la Roche, a Frenchman. Parliamentary sources reported: ‘In this ship Lyon, Prince Rupert and Prince Maurice, with divers other commanders, came in her from Holland, but after three days and three nights storm at sea, not having eaten nor drunk in all that time, these two Princes were in a sick and weak condition, and the ships set to sea again for the North of England, leaving them sick in Holland.’[fn14] The Prince of Orange secured another vessel for Rupert and his party. They set off again, leading a lesser vessel — a galiot — containing weaponry for the coming campaign.

Rupert’s passage was difficult. As his party approached Flamborough Head, on the Yorkshire coast, the Parliamentarian ship the London bore down on them. ‘What are you doing?’ the Parliamentarian captain hollered. ‘We are cruising,’ replied Colster, captain of Rupert’s vessel, while the prince stood next to him in a mariner’s cap. ‘What is the galiot?’ persisted the master of the London. ‘It is a Dunkirk prize,’ Colster lied. The suspicious Parliamentarians insisted that the galiot be searched. Rupert ordered Colster to sail on, prompting the London to summon assistance by firing her cannon. When two more enemy ships appeared on the horizon, Rupert told Colster to head directly for shore.

The prince and his men rowed to safety and landed at Tynemouth. That night the galiot set off again and took its much-needed contents to the Royalist haven of Scarborough.

Rupert wasted no time. He rode for Nottingham, which Charles had made his base, through fields rich with summer crops — the harvest of 1642 was to be especially bountiful. However, he was delayed when his horse lost its footing, throwing him to the ground and dislocating his shoulder. When he eventually reached Nottingham, he found that his uncle had departed for Coventry. Rupert set off south to join him. En route, the prince learnt that Coventry had closed its gates to Charles, its rebel garrison firing on his flag. The king, bewildered by this show of aggression, had moved on to Leicester. Rupert changed direction once more, arriving at Leicester Abbey, where he found his uncle with a tiny army. Its cavalrymen, under Henry Wilmot, had performed poorly in a skirmish. They were immediately entrusted to the prince’s command.

The rank of General of Horse was much coveted. Military manuals of the time insisted that such a position be filled by a figure of rare qualities, reflecting the cavalry’s pre-eminence on the battlefield: ‘Cavalry, so called of Cavallo (which in the Italian and Spanish signifieth a horse) is worthily esteemed a most noble and necessary part of the military profession,’[fn15] recorded a military expert, in 1632. The same authority continued: ‘The General of the Horse, as being one of the principal Chiefs of an army, must be a soldier of extraordinary experience and valour; having in charge the nerve of the principal forces, and on whom the good success of many designs and actions dependeth, as being most usually executed by the Cavalry, especially in battles: where the charging of the enemy in good order usually giveth victory; and contrariwise, the disorders of the Cavalry often disturb and disband the whole army.’[fn16]

The question for more seasoned veterans was whether the smooth-faced Rupert had either the experience essential to such a key position or the ability to transform the ragbag cavalry into a disciplined force. The German prince had bravery, they knew. He also possessed great charisma and style, his impressive figure topped with a plumed hat and ending in fine leather cavalry boots, while his back was swathed in the swish of a scarlet cloak. However, the sum total of his military experience was slight: the action at Rheinberg, four sieges, the cavalry charge at Rheine, and the defeat at Vlotho. Since then, he had been a prisoner of war. He had been absent during three years when some of them had been perfecting their skills on continental battlefields. They looked to Rupert to prove his worth in the crucial, senior position allotted him by his uncle.

On 22 August 1642, when Charles raised the royal standard at Nottingham, it was less a declaration of war than an urgent call for supporters to rally to the Crown. The first night that it flew above the town, the royal standard was blown over. In a superstitious age, this was interpreted as an ill omen for the king’s cause. Certainly, if the Royalists were to have a chance, reinforcements were direly needed: Sir Jacob Astley, the king’s general of infantry, and a former military tutor of Rupert’s, warned that without more men, he could not be sure that he could prevent Charles being ‘taken out of his bed, if the rebels should make a brisk attempt to that purpose’.[fn17] Charles’s army numbered about 2,000 men — a quarter of the size of Parliament’s force, based in Northampton. Some of the king’s men had seen service in the Thirty Years’ War, but most of them were amateurs who were present because of a simple belief that it was their duty to support their monarch. Clarendon recalled the disparity between Rupert’s cavalry and Parliament’s, in the late summer of 1642: the prince’s men ‘were not at that time in number above eight hundred, few better arm’d than with swords; while the enemy had, within less than twenty miles of that place, double the number of horse excellently arm’d and appointed’.[fn18] In London there was optimism that the king’s inability to raise a sizeable army would compel him to bow quickly to Parliament.

Rupert set about equipping and reinforcing his men. The training of horses for battle was as important as the schooling of their riders. John Vernon, who served in the Royalist cavalry, wrote of how best to prepare a horse for war:

You must use him to the smell of gunpowder, a sight of fire and armour, hearing of drums and trumpets, and shooting of guns but by degrees. When he is eating of his oats you may fire a little train of gunpowder in the manger, at a little distance from him, and so nearer by degrees. In like manner you may fire a pistol at a little distance from him in the stable, and so nearer by degrees, and so likewise a drum, or trumpet may be used to him in the stable. The groom may sometimes dress him in armour, using him sometimes to eat his oats on the drum head. In the fields when you are on his back, cause a musket[-eer] and yourself to fire on each other at a convenient distance, thereupon riding up unto him with speed, making a sudden stand. Also you may use to ride him up against a complete armour set on a stack on purpose, that he may overthrow it, and so trample it under his feet, so that by these means, the horse finding that he receiveth no harm, may become bold to approach any object.’[fn19]

By the end of September, Rupert had 3,000 cavalry and dragoons (mounted infantry), most of whom had received some training. He had begun to establish that reputation for tireless energy that was to be his trademark: ‘This Prince, like a perpetual motion’, reported an agitated Parliamentarian historian, ‘with those horse that he commanded, was in short time heard of in many places at great distances.’[fn20] With the myth came hostility and fear. Rupert and his younger brother Maurice were quickly made hate figures by their enemies: ‘The two young Princes, Rupert especially, the elder and fiercer of the two, flew with great fury through divers counties, raising men for the King in a rigorous way … whereupon the Parliament declared him and his brother “traitors”.’[fn21]

Rupert relied on continental military practices, and in so doing revealed what the Earl of Clarendon, an ally but no friend, termed ‘full inexperience of the customs and manners of England’.[fn22] On mainland Europe it was normal to force the local population to fund the army in the field, through levies and confiscations: the Thirty Years’ War general, Wallenstein, invented the dictum, later borrowed by Napoleon, that ‘war should support itself’. In early September Rupert wrote an ultimatum to the mayor of Leicester, demanding £2,000 for the king ‘against the rebellious insurrection of the malignant party’. Although signed by ‘Your friend, Rupert’, there was nothing friendly about the PS: ‘If any disaffected persons with you shall refuse themselves, or persuade you to neglect the command, I shall tomorrow appear before your town, in such a posture, with horse, foot, and cannon, as shall make you know it is more safe to obey than to resist his Majesty’s command.’[fn23]

The startled mayor immediately referred this alien threat to the king, prompting an apology from Charles: Rupert’s letter, he assured the people of Leicester, had been ‘written without our privity or consent, so we do hereby absolutely free and discharge you from yielding any obedience to the same, and by our own letters to our said nephew, we have written to him to revoke the same, as being an act very displeasing to us’.[fn24] Charles was appalled by Rupert’s misjudgement. At this delicate stage, before Leicester had even declared which side it would support, bullying extortion had no place.

Rupert’s gaffe played into the hands of Parliamentary propagandists. From the moment the king’s enemies learnt that Rupert was coming to Charles’s aid, they portrayed him in the blackest light. He was condemned for being sinfully ungrateful for the efforts made on his family’s behalf by England’s Protestants. The prince would never be forgiven for siding against those who had so vociferously championed the Palatine cause.

It was not long before the propagandists presented him to a credulous public as the epitome of immoral soldiery. There was a determination that the most eye-catching of the Royalist leaders should be characterised as wild, dangerous, and even devilish. He was portrayed as a deviant, who enjoyed sex with his white poodle, Boy, and with a ‘Malignant She Monkey’. A Parliamentary pamphleteer enjoyed imagining the creature’s sexual repertoire:

this monkey is a kind of movable body that can cringe and complement like a Venetian courtesan, though her face be not so handsome; yet all her gestures and postures are wanton and full of provocation, she being nothing else (as many others are) but a skin full of lust; her eyes are full of lascivious glances, and generally all her actions do administer some temptation or other; so that she cannot choose but work upon Prince Rupert’s affections; and if he were any thing effeminate as it is not to be doubted but he is forward enough in expressions of love as well as valour; for as the Spanish painter wrote in a Church window sunt with a C. which was an abomination, so her name is an emblem of wantonness, sunt written in that manner being often called a Monkey, which is a kind of prophanation, and thus you see what Prince Ruperts Monkey both nominally and figuratively signify, she being in all her posture the picture of a loose wanton, who is often figuratively called a Monkey.[fn25]

It was not particularly subtle stuff.

His men suffered from similar slanders. Parliamentary printing presses began to use the term ‘cavaliers’ to demonise their enemies. It was an expression of contempt that had arisen from the excesses of the Spanish trooper, the caballo, during the Thirty Years’ War. ‘He’s the only man of all memory’, the author of The Character of a Cavalier stated, ‘whose unworthy actions will perpetuate his memory to ensuing generations. His very name will be odious; and when Posterity … shall find his name mentioned in our Annals, they will be inquisitive to know the Nature of the Beast: This Skellum, this Nigro carbone notatus, this Monstrum horrendum.’[fn26]

Parliamentary leaders encouraged people to give money and silver to their cause, rather than remain vulnerable to ‘several sorts of malignant men, who were about the King; some whereof, under the name of Cavaliers, without having respect of the laws of the land, or any fear either of God or man, were ready to commit all manner of outrage and violence; which must needs tend to the dissolution of the Government; the destruction of their Religion, Laws, Liberties, Properties; all which would be exposed to the malice and violence of such desperate persons, as must be employed in so horrid and unnatural an act, as the overpowering [of] a Parliament by force.’[fn27] Violent, destructive, malicious, and overwhelmingly dangerous: Parliament’s image of the cavalier had taken form before Rupert’s arrival in England. However, he was presented as the quintessential example of this cursed phenomenon.

Meanwhile, the Royalists wanted Rupert — ‘our most Gracious Prince’ — to be seen as a positive influence on their admittedly undisciplined force. He was adamant, they argued, that his troopers ‘should behave themselves fairly, not doing any harm, to man, woman, or child, giving them strict Command, that they should commit no Outrage whatsoever against any of His Majesty’s loving Subjects, neither should they take any thing from them by violence’.[fn28] When any of his men’s crimes were reported to him, it was claimed, Rupert dished out swift and decisive justice.

Among Parliamentary pamphleteers, there were occasional flashes of honesty about the shortcomings of some of their own: ‘I answer that it is true indeed that some of the Parliament’s army are as bad as the Cavaliers’, one conceded, ‘and such as are a very shame to the cause they pretend to stand for, & it were to be wished they were all cashiered, although there were but Gideon’s army left behind.’[fn29]

A generation before the outbreak of war, Henry Peacham had written an unflattering description of the typical English gentleman: ‘To be drunk, swear, wench, follow the fashion, and to do just nothing, are the attributes and marks nowadays of a great part of our Gentry.’[fn30] The Cavaliers were credited with all these debauched and dissolute ways. Fear of their capabilities was heightened as hostilities increased.

The recipients of this nickname, however, were keen to cast themselves in a more forgiving light. One writer in early 1643 talked of ‘the Cavaliers, whom now we see with our eyes to be the Flower of the Parliament, Nobility and Gentry of the Kingdom’.[fn31] An imaginary conversation in The Cavaliers’ Catechism broadened the theme:

Question: ‘What is your name?’

Answer: ‘Cavalier.’

Question: ‘Who gave you that name?’

Answer: ‘They who understood not what they did when they gave it; for it was intended to my infamy, but it proves to my dignity, a Cavalier signifying a Gentleman who serves his King on horseback.’

Question: ‘I pray you tell me what Religion you are of, for it is generally reported of you Cavaliers that you are all most infamous livers, atheists, Epicures, swearers, blasphemers, drunkards, murderers, and ravishers, and (at the least) Papists.’