Полная версия

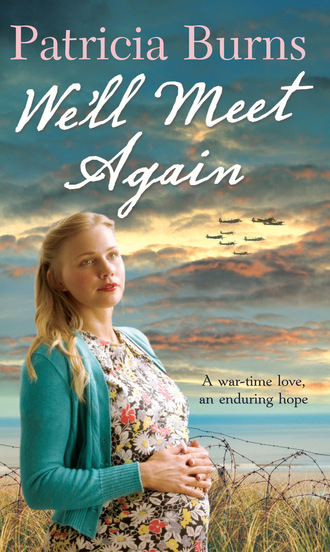

We'll Meet Again

‘But you’ll get time off, surely?’ Gwen said. ‘He won’t have you working in the evenings. We can go to the pictures together.’

‘Yes—’ Annie tried to be optimistic. ‘He can’t keep me in all the time, can he? We’ll go to the pictures Friday nights.’

‘Cary Grant …’ Gwen sighed. ‘Humphrey Bogart …’

‘Clark Gable …’ Annie responded.

‘Who would you like to be, if you was a film star?’ Gwen asked.

‘Judy Garland.’

How wonderful to be Dorothy and meet the Tin Man and the Cowardly Lion … how wonderful to escape from your farm and land in Oz. But of course you had to live in Kansas for that to happen to you. Whirlwinds didn’t tear across Essex.

‘Judy Garland? Oh, no. I want to be glamorous. I want to be Vivien Leigh.’

And meet Rhett Butler.

‘Oh, yes …’ Annie sighed.

Both happy now in their fantasy world, the girls marched arm in arm along the dusty summer streets of Wittlesham-on-Sea. The neat terraces of guest houses leading to the sea front still had ‘Vacancies’ notices hopefully displayed in their front windows, but many of the gardens had their roses and geraniums replaced by lettuces and peas as people answered the call to dig for victory.

When they reached the sea front, they stopped automatically and looked towards the pier.

‘Quiet, isn’t it?’ Gwen said. ‘My mum says it’s hardly worth keeping open.’

Gwen’s mum ran The Singing Kettle, a tearoom fifty yards from the pier entrance. The previous summer, the last summer of peace, it had been a little gold-mine, and Gwen had been kept as busy as Annie, running from kitchen to table with trays of teas and cakes and sandwiches, and back again with piles of dirty crockery. This year the visitors were few and far between. People were reluctant to go on holiday when invasion forces were threatening just across the Channel.

‘Blooming Hitler,’ Gwen grumbled as they surveyed the sprinkling of holiday-makers and the barbed wire entanglements running the length of the beach. ‘Gone and ruined everything, he has. That’s what my mum says.’

‘Yes,’ Annie agreed. ‘We’ve had to plough up the fields by the road because of him.’

Digging for Victory had meant that her father had had to change some of his farming practices. He hadn’t liked that at all, and she and her mother had been the ones to bear the brunt of it.

The girls turned away from the pier and strolled along together towards the southern end of the promenade. Even fewer businesses were open here, and the locked doors and boarded-up windows gave the prom a forlorn air.

‘D’you really want to go and work at Sutton’s Bakelite?’ Annie asked.

Gwen shrugged. ‘It’s good money, and it’s all year round,’ she pointed out.

Year-round jobs were at a premium in Wittlesham, where seasonal work was the norm.

‘Yes, but Sutton’s—Beryl’s dad,’ Annie persisted.

‘I know—’ Gwen said.

Both of them thought of Beryl Sutton, their sworn enemy.

‘—but it is war work. I’ll be making parts for aeroplanes and stuff. Wirelesses, that sort of thing,’ Gwen said.

‘I s’pose so. But Toffee-nose Beryl—’

‘Swanky knickers—’

‘Posh pants—’

They giggled happily, dragging up every insult they’d ever thrown at Beryl. But it still didn’t help with the deep jealousy Annie harboured, swilling like poison in her gut. Beryl had been allowed to go to the grammar school, when Annie had always beaten her in every school test they ever did. On top of that, they shared a birthday. Somehow, that made it much worse.

‘She won’t be there,’ Gwen pointed out.

No, Annie thought. She’ll be at school, for another two years. Lucky cow.

‘And her dad’s all right.’

‘Yes.’

That was another thing. Beryl’s dad was all right. He was nice. He was big and cheerful and adored Beryl. But then Gwen’s dad adored her, too. He called her his little princess and slipped her money for treats with a wink and a ‘Don’t tell your mother.’ Annie sighed. It wasn’t fair.

The closed up souvenir shops and cafés dwindled into bungalows as the cliff ran down towards the marsh at the edge of the town. As the sea wall joined the end of the prom, there was a no man’s land of nettle-infested building plots and little wooden holiday chalets on legs that was not quite town but not country either. The roads here were just tracks and there was a temporary feel about the place. On the very last plot, a field under the sea wall that took a corner out of Annie’s father’s land, was a holiday chalet called Silver Sands. It belonged to the Suttons, who let it out to summer visitors.

‘Looks like they’re opening it up,’ Annie said.

She was right. The windows and doors were open and the net curtains were blowing in the breeze. Rugs hung over the veranda rails. From inside came the sound of someone banging around with a broom.

‘Trust the Suttons to get lets when no one else can,’ said Gwen. ‘There’s a lot of people in this town don’t know what they’re going to do if this war goes on much longer. My aunty May’s desperate. She’s only had two families so far this summer, and lots of her regulars have cancelled. And my uncle Percy, he can’t work, not with his chest. And, like she says, rates’ve still got to be paid, and the gas and electric and everything, and the rooms kept nice, whether there’s visitors or not. She was talking to my mum about it the other day. Went on about it for hours, she did.’

‘Yes,’ Annie said.

Her eyes were on Silver Sands. It was a trim little place, painted green and cream with sunray-effect woodwork on the veranda rails. Around it was about half an acre of wild ground with roughly cut grass, a few tough flowering plants and a swing. Positioned as it was, right next to Marsh Edge Farm, it had always held a special place in her imagination. When she was little, she liked to picture herself creeping in and living there, safely out of the way of her father, her own small palace where she could order everything the way she wanted.

‘I wish it was mine,’ she said, without really meaning to let it out.

‘It’s only a holiday chalet like all the rest,’ Gwen said. ‘I dunno why you make such a fuss about it. You wasn’t half mad when the Suttons bought it! I thought you was going to burst a blood vessel!’

‘Well, why should they have it? Them, of all people? That Beryl …’

Annie’s voice trailed off. There, on the track leading to the chalet, was Beryl. It was as if she had been summoned like a bad genie by Annie’s speaking her name. Annie took in her grammar school uniform, the green and white checked dress, the green blazer, the straw hat with its green ribbon and green and yellow badge. Her guts churned with jealousy.

‘Ooh—’ she jeered. ‘It’s the posh girl. Look at her soppy hat! What’re you wearing that hat for, posh pants? Looks like a soup plate!’

‘Soup plate on her head!’ chimed the faithful Gwen.

Beryl glared at them. She was a solid girl with brown hair cut in a straight fringe across her broad face and thick calves rising from her white ankle socks. The school uniform that Annie envied so much did nothing for her looks.

‘Common little council school brats,’ she countered, her lip curling into a full, cartoon-sized sneer. She glanced behind her. ‘Come on, Jeffrey. Mummy doesn’t like us talking to nasty little guttersnipes. They might have nits.’

It was only then that Annie noticed Jeffrey Sutton, Beryl’s younger brother by a year, sloping up along the track towards them. He was also in grammar school uniform, his leather satchel over his shoulders, his green and black striped cap pushed to the back of his head. It was unfortunate for Beryl that she took after her mother while her three brothers favoured their father, for the boys had the better share of the looks. Jeffrey caught up with his sister and threw Annie and Gwen a conciliatory grin. You never knew which way Jeffrey might jump. His loyalties depended upon the situation.

‘Wotcha!’ he said.

Beryl rounded on him. ‘Jeffrey! Ignore them.’

Jeffrey shrugged and walked on, opting out of the situation. As he went, he said, ‘Bye!’

It was difficult to know who he was speaking to, but Annie leapt on the one word and appropriated it.

‘Bye, Jeffrey,’ she said, as friendly as could be.

She was rewarded by a look of intense annoyance on Beryl’s face.

‘So you’re going to be one of my father’s factory girls, are you?’ she said to Gwen, breaking her own advice of ignoring Gwen and Annie.

‘I’m going to be earning me own living,’ Gwen retorted. ‘Not a little schoolgirl in a soup plate.’

‘You are so ignorant, Gwen Barker,’ Beryl said, and stalked off up the track and in at the gate of Silver Sands.

‘Ooh!’ Gwen and Annie chorused and, linking arms again, marched after her, past the gate and on towards the sea wall. As they dropped arms to take a run at the steep slope, Beryl’s mother came out on to the veranda, her face set in lines of disapproval.

Annie couldn’t resist. She gave a friendly wave.

‘Afternoon, Mrs Sutton!’ she called cheerfully and, before Mrs Sutton had a chance to reply, the pair of them raced up the grassy bank, over the bare rutted path at the top and slid down the other side. They landed in a heap at the bottom, giggling helplessly and scratched all up their bare thighs from the sharp grass blades.

‘Did you see her face?’ Gwen chortled.

‘Sour old boot!’ Annie gasped.

It was warm and still at the foot of the sea wall, for the wind was offshore. There was a smell of salt and mud and rotting seaweed on the air. The very last of the Wittlesham beach was at their feet, a narrow strip of pale yellow sand and shingle that dwindled to nothing fifty feet to their right where it met the marsh.

Annie wrapped her arms round her legs and rested her chin on her knees, staring through the barbed wire entanglements, out across the fringe of grey-green marsh and wide expanse of glistening grey-brown mud to where the waters of the North Sea started in lace-edged ripples. It was friendly today, in the height of summer, the sunlight glinting off the gentle green waves. She let the peace steal into her with the heat of the sun. A curlew uttered its sad cry. She felt safe here.

‘Jerries are over there, across the water,’ Gwen said.

‘Mmm,’ Annie said.

That was what they said, on the wireless. It was difficult to believe right here, sitting in the sunshine.

‘My dad’s out every evening, drilling with the LDVs. No, not that. The Home Guard, it now is. Mr Churchill said.’

‘My dad doesn’t hold with it,’ Annie said.

But then her dad didn’t hold with anything that meant cooperating with anyone else. And her dad would be expecting her home soon. She didn’t own a watch, so she had no idea of the exact time, but her dad knew when school ended, and how long it took to walk home. Reluctantly, she stood up.

‘S’pose I’d better go,’ she said with a sigh.

‘You got to?’ Gwen asked. ‘It’s the last day of school. It’s special.’

Gwen’s mum had promised her a special tea, and then they were all going to the pictures—Gwen, her sister and her mum and dad.

‘Not in our house, it isn’t,’ Annie said. ‘Have a nice time this evening. Tell me all about it.’

They scrambled to the top of the sea wall again. Gwen set off towards the town. Annie stood for a moment watching her, then turned and ran down the landward side and up the track beside Silver Sands. She couldn’t help glancing over the fence at the little chalet in its wild garden but, though the windows were still open, none of the Suttons were outside. She skirted round the back of the garden and struck out across the fields. The newly expanded dairy herd grazed the first two. Then there was an empty field that had been cut for silage. Ahead of her across the flat land, she could see the square bulk of the farmhouse and the collection of sheds and barns round the yard. Marsh Edge Farm. Home. It gave her a sinking feeling.

One field away from the house, Annie climbed over the gate and on to the track that led from the farm to the Wittlesham road. She looked at the yard as it grew steadily nearer. Was her father there? She started counting—an odd number of dandelions before she reached the hawthorn tree meant he was there, an even number meant he wasn’t. Nineteen—twenty—twenty-one. Bother and blast. Try again. If she could hold her breath as far as the broken piece of fence he wouldn’t be there …

She reached the gate into the yard. In winter, it was a sea of mud, but now, in summertime, it was baked into ruts and ridges in some places and beaten to dust by the passing of cattle hooves twice a day in others. Hens strutted and scratched round the steaming midden in one corner, the tabby cat lay stretched out in the sun by the rain barrel. A gentle grunting came from the pig pen. Annie started to relax. Perhaps he was in one of the fields on the other side of the farm. She could go in and have a cup of tea with her mum.

Then there was a sudden flutter and squawk from the hens, and out of the barn came her father. He stopped when he saw her and fixed her with his pale blue eyes.

‘You’re late,’ he said.

CHAPTER THREE

ANOTHER long day of work was done and the last chores in the farmyard were finished. Annie looked in at the kitchen door. Her mother was sitting at the big table, turning the wheel of her sewing machine. The needle flew up and down so fast that it became a blur, while her mother fed the long side seam of a green silk dress beneath it.

‘Mum?’ Annie asked. ‘You all right? You need me to do anything?’

‘No—no—’ Edna Cross did not take her eyes from the slippery fabric. ‘Just want to get this done before Mrs Watson comes for her fitting tomorrow.’

‘I think I’ll go out for a bit, then.’

‘All right, dear.’

Annie slid out of the porch, ran across the yard and away down the track before her father could see what she was doing. Once over the gate into the first field, she slowed to a walk. She felt physically light, as if she might bounce along if she wanted to. For a short while, until it got dark and she had to go back indoors, she was free.

She headed automatically for the sea wall. It was no use looking at Silver Sands, for a big family had moved in two days ago for a holiday. Even from here she could see the two little tents they had put up in the garden because the chalet wasn’t large enough to accommodate them all. But it would be all right the other side of the wall. That was one advantage of the barbed wire—it kept people off the beach. Nobody but her liked to sit on the small bit of sand between the wall and the wire.

It was a beautiful summer’s evening, warm and still. Annie dodged the cow-pats and the thistles, singing as she went.

‘Wish me luck as you wave me goodbye …’

The one big bonus of the war, as far as she was concerned, was that her father had gone out and bought a wireless so he could listen to the news each evening. Which meant that they could also listen to Henry Hall and Geraldo, and her mother could have Music While You Work on. Now she knew all the latest songs just as soon as Gwen did.

As she came nearer to Silver Sands, she could see the family there out in the garden. She felt drawn to study them. There were two women—Mum and Aunty, maybe?—sitting on the veranda knitting, together with a man reading a newspaper, while a bunch of children all younger than herself were running round the bushes and up and down the steps in a game of ‘he’. Annie skirted the garden, wishing there was another way on to the sea wall, but you had to walk a long way away from the town before you got to the bridge over the wide dyke that ran along behind the wall. There were shrieks from the children as someone was caught, and then yells of, ‘Joan’s It! Joan’s It!’ Annie wondered what it would be like to have a holiday. It must be nice to be able to play all day long like those children. Not that she was wanting to run around playing now, of course. She was too grown up for that. But she would have liked it when she was little.

She ran up the sea wall, stopping at the top to look about.

‘Oh!’ she said out loud.

For there, just below her on the seaward side of the wall where nobody ought to be, was a boy a year or so older than herself with a sketch-book on his knee.

If he had heard her, he made no sign of it, but just kept on glancing at the sea then looking down at his paper and making marks. Fascinated, Annie looked over his shoulder. He was making a water-colour sketch. The sky was already done and, as Annie watched, he ran layers of colour together to make the sea, leaving bits of white paper showing through so it looked like the low sunlight reflecting off the waves. He made it look so easy, so unlike the clumsy powder paint efforts that she had occasionally been allowed to do at school.

‘That’s ever so good,’ she said before she could stop herself.

The boy turned his head, screwing up his eyes a little to see her as she stood against the light.

‘Oh—’ he said. ‘Hello. I mean—thanks. I thought you were one of my beastly kid cousins creeping up on me.’

He had an angular face with broad cheekbones, and very dark hair cut in a standard short-back-and-sides, but what struck Annie most was his unfamiliar accent—something she vaguely identified as being northern.

‘No,’ she said.

Now that she had started the conversation, she wasn’t quite sure what to say next.

‘You an artist?’ she blurted out, and instantly curled up inside with embarrassment, because how could he be an artist? He wasn’t old enough.

But, to her relief, instead of laughing, he took her question seriously.

‘I want to be. But I don’t know whether I’m going to be good enough.’

‘But you are! That’s lovely!’ Annie cried.

He shook his head. ‘Not really. The colours aren’t right.’

‘They are—well, nearly,’ Annie said, sticking to the truth. ‘And it’s—’ She stopped and considered, her head to one side. She’d never really looked at a painting before, not a proper one. She had no words to describe what she thought about it. ‘It’s like—moving. Yes—that’s it. The sea’s sort of moving—’

It sounded daft, put like that, because paint didn’t move. But the boy’s face lit up. He had an infectious smile.

‘Really? You think so?’

Glad that she’d hit the right note, Annie grinned back. Without thinking about it, she came and sat down by him. He was dressed in a blue short-sleeved shirt, khaki shorts and plimsolls. His arms and legs were long and skinny. His nose was peeling.

‘I do, honest. I think it’s good,’ she assured him. ‘Are you going to put the pier in? And the wire?’

‘When it’s dry I’ll draw the pier in Indian ink, so I’ll be able to get all the little details. I don’t know about the wire. I think I might do another one, without the pier, just sea and sky and the wire across it.’

Annie nodded slowly, seeing it in her head. ‘Yes, sort of … like a prison—’ The boy turned and gave her a long, considering look.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘That’s just it. It’s supposed to be keeping the Jerries out, but if you look at it the other way, it’s keeping us in.’

‘But if you look through it—sort of fuzzy your eyes—you know? You can pretend it isn’t there at all,’ Annie said.

Which brought on that dazzling smile again.

‘Yes! That’s what I’m doing right now! Just—making it go away. How did you know that?’

‘I do it a lot,’ Annie told him. ‘Pretending things aren’t there. Or people. It’s better like that.’

‘And how,’ the boy said.

They looked at each other, breathless, startled by that heart-stopping moment that revealed a kindred spirit.

‘I’m Tom. Tom Featherstone.’

That intriguing accent. The way he said ‘stone’.

‘Annie Cross.’

Self-consciously, they shook hands. Tom put down his sketch-book and brushes.

‘Are you here on holiday?’ she asked.

‘Mmm. At the chalet.’

‘Silver Sands?’

If it had been anyone else, she would have resented them being in the place she wanted for her own retreat, but with Tom it was different.

‘S’right.’ he said. ‘You?’

‘I live at the farm. Marsh Edge. Over there.’

She pointed her thumb over her shoulder.

‘Oh—that farm. We can see it from the garden. I wondered who lived there.’

‘I wondered who the family was at Silver Sands. I saw the tents in the garden. I thought—I thought it must be nice, to have a holiday, and lots of people to play with. If you’re a little kid, of course.’

‘They’re pests, my cousins,’ Tom said. ‘They’re all younger than me. My sister Joan’s five years younger than me, and my cousin Doreen’s only a year younger than her, so they’re friends, and then the twins, that’s Doreen’s brothers, they’re always together anyway. I came over here to get away from them.’

It was all falling into place.

‘Who are the grown-ups? They your mum and dad?’

‘My mam and Aunt Betty and Uncle Bill. My dad had to stay at home and mind the business.’

Mam. She liked that.

‘Where’re you from?’ she asked.

‘Noresley. It’s near Nottingham.’

Nottingham. Annie pictured the map of England in her head. They’d traced it and put in all the boundaries and principle towns and cities in Geography a couple of years ago. Nottingham was just about in the middle. The Midlands.

‘Where Robin Hood came from?’

‘Sort of. We’re not in Sherwood Forest, though. It’s all pit villages round our way.’

‘Pits? You mean coal mines?’

Miners were one of her father’s many dislikes. They were all good-for-nothing commies in his opinion.

‘That’s right. We run a bus and coach company, in and out of Nottingham and Mansfield, and between the villages.’

Annie thought of being out and about all the time, driving from one place to another, talking to all the people getting on and off the bus.

‘Sounds like fun. Are you going to drive a bus when you’re older?’

Tom sighed. ‘I suppose I’ll have to. I can’t really see my dad letting me go to art school. Depends, though, doesn’t it? If the war’s still going on by December next year I’ll be joining up.’

‘D’you think it’ll go on that long?’

‘Last one did, didn’t it? It went on for four years.’

‘Four years! I’ll be eighteen then.’

Eighteen. It seemed a huge age. And where would she be then? Still here at Marsh Edge Farm, probably. Or … Annie looked at the barbed wire that was supposed to keep the Germans out and a dreadful thought struck her.

‘Do you think they will invade?’ she asked.

It had never really presented itself as a possibility before. It was something lingering on the edge of imagination, like a past nightmare. Now she saw waves of grey-uniformed soldiers coming ashore, cutting through the wire, marching over the fields—her fields—towards her home. Fear sliced through her.

‘I don’t know,’ Tom said. ‘We’re winning the Battle of Britain so far. Our planes are shooting down more of their planes. We can’t lose, can we? I mean—we just can’t—’

‘No,’ Annie agreed. ‘We can’t.’

They both stared through the wire to the horizon. The fear subsided, but still lurked there.

There was a rustling and panting on the other side of the wall, and then two shrill voices broke through their reverie.

‘Tom! Tom! Your mam says you’re to come in, she’s making the cocoa.’

Annie turned round. Two small boys with identical round faces, grey eyes and grubby knees were staring at her.

‘Who’s she?’ one of them asked.

‘Never you mind. Go and tell my mam I’m just coming,’ Tom told them.

The twins stood and gazed.

‘What’s she doing here?’ the other one asked.

‘Talking. Now buzz off. Now! Hop it! Go!’ Tom ordered.

Giggling, they went.

‘Brats,’ Tom grumbled.

‘I thought they were quite sweet,’ Annie said.