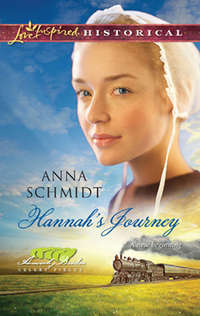

Полная версия

Family Blessings

Jeremiah Troyer is a romantic, she thought and bit her lip as she focused all of her attention on rolling out crusts for pies instead of dwelling on the handsome newcomer who was to be their neighbor—and perhaps business associate. Neighbor and business associate, Pleasant sternly reminded herself, and nothing more.

If there was one lesson she had learned, it was that men were rarely as they presented themselves to others. Or perhaps it was that she was a poor judge of the male species. After all, she had foolishly thought that a young man from Wisconsin was flirting with her, calling at the bakery day after day just to see her. More to the point, the man she had thought Merle was before they married and the man he had turned out to be were not at all the same.

Hannah and others had tried to warn her, but she had insisted that they simply did not understand people like Merle and her—serious people who were devoted to their work and who understood the hard realities of life. But even she was not prepared for day in and night out of living with a man who saw little good in anyone or anything—including her and his own children.

The shop bell jangled and Pleasant sighed heavily as she wiped her hands on her apron and headed to the front of the store. “Did you need more doughnuts, Herr Troyer?” she asked as she stepped past the curtain separating the kitchen from the shop and saw Hilda standing there with all four of Pleasant’s children.

“Pleasant, you must do something with this girl,” her sister-in-law said as she pushed Bettina forward. “I am quite at my wit’s end.”

Chapter Three

“Bettina, are you all right? Has something happened?” Pleasant asked, coming around the counter and kneeling next to her daughter whose face was awash in silent tears.

“I didn’t know they had wandered off,” the girl said in a whisper as Pleasant wiped away her tears with the hem of her apron.

“Shhh,” Pleasant murmured. “It’s all right.”

“It is not all right,” Hilda thundered. “For it was your idea to give the child responsibility for making sure the twins are properly brought to my house before she and Rolf leave for school.”

On weekdays, when the bakery was busiest, the twins stayed with Hilda who had seven children of her own. On Saturdays, they spent their day at the bakery with Pleasant while Rolf and Bettina took care of chores at home.

“I wanted to get the wash hung before …” Bettina began.

Pleasant stood up so that she was eye to eye with Hilda. Merle’s sister had first watched over the children after their mother’s death, taking them in so that Merle could tend his celery fields. And even after Merle and Pleasant married, she had continued to insist that the children spend their days at her home, persuading Merle that it was asking too much of them to accept Pleasant right away. But when Pleasant had accepted this arrangement without question and gone back to helping her father in the bakery, Hilda had done a complete about-face, complaining to Merle that Pleasant was ignoring the children, not to mention her duties as his wife and the keeper of his house.

Pleasant kept one hand around Bettina’s shoulder as she tried to assure herself that only fear and panic would make Hilda speak so sharply in front of the children. “Hilda,” she said quietly, “the children are all safe. She’s only a girl and …”

“At her age their father was already working a paying job. At his age …” Hilda gestured toward Rolf. “He was …”

Pleasant touched her sister-in-law’s arm. “Hilda, please,” she murmured and was relieved when the woman swallowed whatever else she had been about to say.

Meanwhile, the twins had eased away from the drama and worked their way behind the counter where they had opened the sliding door of the bakery case and were helping themselves to some of the sweets that Jeremiah had not purchased. Bettina tugged on Pleasant’s skirt and nodded toward the boys.

“Stop that this instant,” Pleasant demanded as she moved quickly around the counter and picked up one twin under each arm like sacks of flour.

When she failed to take away the pastry each boy clutched, Hilda snorted. “You do them no favors by indulging them,” she huffed as Pleasant deposited both boys closer to the door.

“Tell your Aunt Hilda that you’re sorry for causing her worry and then apologize to your sister as well,” Pleasant instructed.

“Sorry,” Henry muttered even as he stuffed the last of his pastry into his mouth.

Pleasant grabbed an empty lard bucket she kept under the counter to collect waste and shoved it under Henry’s chin. “Spit it out,” she said in a voice that brooked no argument. The boy did as he was told and then burst into tears. Within seconds his twin had joined in the chorus and the racket they made was deafening.

Hilda threw up her hands. “Do you see what you’ve done?” she demanded and Pleasant prepared to defend her action until she saw that her sister-in-law had addressed this remark to Bettina.

Pleasant realized that if she didn’t do something at once, her father—or worse—any customer who came in was going to find the shop crowded with crying children. “Let’s all just calm down and have a nice glass of milk in the kitchen,” she suggested just as the bell above the door jangled.

“Ah, Frau Yoder,” Jeremiah Troyer said, ignoring the chaos of the overwrought children. “I thought that was you I saw coming down the road before.”

Beyond caring why Jeremiah Troyer had invaded the bakery for a third time that morning, Pleasant seized the opportunity to herd all four children into the kitchen. She noticed that all sign of tears and protests had abated the minute Jeremiah entered the bakery. The children seemed quite fascinated by him.

“Sit there and be quiet,” Pleasant said, indicating a long bench that ran along one wall. She was glad to see that even the twins seemed to recognize the limits of her patience. While she poured four glasses of milk and handed one to each child, she tried in vain to overhear the conversation taking place in the shop. Then she heard the opening and closing of the outer door and a moment later, Jeremiah stepped into the kitchen.

“May I have a word with Rolf, Frau Obermeier?” he asked.

“What about?” Pleasant asked.

Jeremiah gave her that maddening smile of his and tousled Rolf’s hair. “With your permission, Frau Yoder has suggested that he might be a candidate to help out at the ice cream shop.”

Rolf’s eyes widened with a mixture of such surprise, unadulterated joy and pleading that Pleasant’s heart sank. This was the most difficult part of being a parent. She was going to have to say no.

“I don’t believe that would be a good idea,” she said.

Rolf’s face fell but he said nothing. Jeremiah’s smile tightened. “I see. Perhaps this is not the right time.” He glanced at Bettina and the twins and seemed to focus on their tear-stained faces. “Forgive me for the intrusion, ma’am. We can discuss the matter later.” He nodded to the children and headed for the door.

“Wait a minute,” Pleasant said, hurrying after him.

He had opened the door and the bell was still vibrating when she caught up to him. “I know you mean well, Herr Troyer, but …”

“Are the children all right?”

Pleasant blinked up at him. “Yes, of course they are.” Why would he think otherwise? She saw a flicker of doubt cross his expression and felt her defenses go on alert. “Herr Troyer, please understand that Rolf has his schooling and chores at home and …”

“As do many other children.” The implication that other boys Rolf’s age were working or learning a trade was clear.

“The children are my responsibility,” Pleasant said tightly. “I will decide when the time is right that they should take on more than they must already manage.”

Jeremiah looked away for an instant, out the leaded glass of the bakery door. “Of course, you know best, but if I may offer an observation as someone who was once smaller and not nearly as strong as others my age?” He seemed to wait a beat for her to grant permission and when she said nothing, he continued, “Do not deny the boy the opportunity to find his place in the world.”

“He is only twelve,” Pleasant protested. “Besides, he will one day have his father’s farm to manage and …”

“I am not speaking of his life as an adult. I am speaking of his life now—the things that will surely shape the man he will one day become. There is a tempest building in that boy. A growing view of the world and those around him as unfair. He is fast approaching a crossroads where he will either accept his size as a challenge to be met or he will surrender himself to the belief that he has been unjustly punished.”

Pleasant thought of Hannah’s son Caleb and how he had run away. Everything there had turned out for the best, but Rolf was different. Small and quiet—too quiet, she had often thought. And Merle had been especially hard on the boy.

“Why are you really reluctant to have your son work for me?” Jeremiah asked. “Or perhaps it is not just me? Perhaps you are reluctant to let him go?”

She looked up at him as if truly seeing him for the first time. His dark wavy hair was the color of chestnuts. His eyes were the gold-and-green hazel of autumn leaves in his native Ohio and they held no hint of reproach, only curiosity. His expression was gentle and reflected only a deep interest in her reply.

I am afraid, she thought and knew it for the truth she would not speak aloud. “I will think on what you have said,” she replied. “I respect that you have seen in Rolf perhaps some of your own youth, but I would remind you that he is not you—nor your son.”

“Nein,” Jeremiah whispered, glancing away again. “A friend then? Could we—you and your children and I—not be friends?” He arched a quizzical eyebrow and the corners of his mouth quirked into a half smile.

“Neighbors,” she corrected.

He grinned and put on his hat. “It’s a beginning,” he said. “Good day, Pleasant.”

“Good day,” she replied without bothering to correct his familiarity. She watched him hop off the end of the porch closest to his shop and thought, And perhaps in time, friends.

There had been one reason and one reason only that Jeremiah had gone to the bakery for a third time in the same morning. He had been sitting outside the hardware store sharing doughnuts with the Hadwells when Mrs. Hadwell had noticed Hilda herding Pleasant’s children down the street. The girl was in tears and the three boys lagged behind her and their aunt, looking distraught.

Mrs. Hadwell had cleared her throat, drawing her husband’s attention and then she nodded toward the little parade passing their store. Roger Hadwell glanced up and then turned back to the conversation he and Jeremiah had been having about remodeling Jeremiah’s shop. But Jeremiah knew that look. He’d seen similar glances pass between neighbors and friends of his family his whole life. Louder than a shout it was a look that warned, “This is none of our business. Stay out of it.”

And to his surprise, Jeremiah found it easier to comply with that unspoken warning than to call out to Hilda Yoder and ask if there was a problem. To his shame he lowered his eyes until Hilda had passed by on her way to the bakery, her fingers clutching the thin upper arm of Pleasant’s daughter. But the scene stayed with him even as he headed back to his own shop and even after he forced himself to focus on the plans for remodeling the space. And when he heard one of the children cry out, he could stand it no more and headed for the bakery.

With no real plan in mind, he was a bit taken aback when he passed the bakery window and saw Pleasant thrust a bucket under the nose of one of the younger boys. Perhaps the child was ill. Perhaps he had misread the entire situation. He entered the bakery, closing the door with an extra force that he knew would cause the bell to jangle loudly. It worked. Everyone turned to him. Instinctively, he focused his smile on Hilda Yoder who scowled at the interruption while Pleasant said something about milk and took advantage of his arrival to take the children into the back room.

“What is it now, Herr Troyer?” Hilda snapped.

Jeremiah had no idea what he should say. He racked his brain for some reason why he might have needed to have dealings with the woman.

“I saw you come down the street earlier and then it occurred to me that you might be just the person to give me some advice.” He suspected that giving advice was Hilda’s stock in trade and when her scowl shifted from irritation to suspicion, he was pretty sure that he had guessed correctly.

“What sort of advice?”

Jeremiah chuckled. “I may know how to manage a business and make a decent ice cream, but when it comes to decorating the premises …” He shrugged. “I am quite at a loss.” He could practically see the wheels turning in Hilda’s brain and hurried on to press his advantage. “Clearly, I’m going to need tables and chairs and a serving counter and …”

Hilda nodded, her small light eyes flitting back and forth as if typing up a list. “Have you colors in mind?”

Jeremiah shrugged.

Hilda huffed out a sigh that, when translated, meant, “Men are hopeless,” and set to work ticking off what he was going to need. “The place is a mess. You’ll need cleaning supplies and then paint—a lemon-yellow I would think. Stop by the store this afternoon and I’ll have Herr Yoder pull together those initial supplies. In the meantime, you can order tables and chairs and the counter from Josef Bontrager. He’s an excellent carpenter.”

“Frau Yoder, you are a blessing in disguise. How will I ever thank you?”

“You can pay your bills in cash and at the time of delivery,” she informed him without a trace of humor.

“Of course. Thank you. I’ll be by right after lunch if that’s convenient.”

Hilda nodded and headed for the door. She appeared to have forgotten all about the business that had brought her and the children here in the first place.

“I’ll need a helper,” Jeremiah said as he hurried to open the door for her. “Perhaps you know of a young boy who …”

“My older boys all work in the celery fields,” she said, making the assumption that her sons would be at the top of Jeremiah’s list. She glanced toward the kitchen. “Perhaps Rolf—he’s too small for field work.”

“Another excellent suggestion. Thank you,” Jeremiah said as he ushered her out and closed the door behind her.

It had been a stroke of genius or more likely God’s divine guidance that had made him ask her advice on a helper. The one thing he understood was that Hilda Yoder took great pride in seeing herself as invaluable to others when it came to handling their affairs. He did not consider what he might do if she were to suggest that he hire one of her seven children. But as things turned out that should have been the least of his concerns. He had been totally unprepared for Pleasant Obermeier to reject his offer. He had seen the dead and baked fields behind her house. Surely she could use the money the boy could bring home.

He stood for a moment looking down the road at the large white-washed house with its tin roof and wraparound porch where she had lived with her late husband and where she now lived with his four children. He glanced back at the bakery where, according to his great-aunt Mildred, she had spent a good portion of her life helping her father run the business even after she had married Merle Obermeier.

Jeremiah had lived most of his life in a house where dreams were frowned upon and only hard work was respected. And until he had gone to work for Peter Osgood, he had followed that regimen, burying his dreams in order to try and please his uncle. Now he could not help but wonder what dreams Pleasant had put aside in order to care for first her widowed father and then her half sisters and finally the widower and his four motherless children.

He remembered how, after his father had died, his own mother had abdicated the raising of the children to her brother-in-law. That was to be expected for Jeremiah’s father—a kind but timid man—had always bowed to his older brother’s wishes as well. How many times had Jeremiah wished that his mother would stand with him when he tried to challenge his uncle’s rigidity?

Oh, Pleasant, he thought, do not make the mistake my mother made.

But it was hardly his concern, he reminded himself. He had a job to attend to as well as a business to get up and running. His fascination with the baker and her children was nothing more than that—idle curiosity, and as his uncle had reminded him more than once and emphasized with the back of his hand, idle thoughts were the devil’s workshop.

Chapter Four

Pleasant had underestimated the amount of time she would have to devote to creating the ice cream cone recipe. In spite of the fact that the bakery’s business had dwindled to the basics—breads, rolls and the occasional pie or dozen cookies—she was still busy from dawn to well after dusk. Merle’s house was a large one and required constant cleaning to keep it presentable. With four growing children there was a great deal of washing and ironing to be done on top of the cooking she did at home and the upkeep of the kitchen garden she relied upon for fresh produce to feed herself and the children.

Then there was the celery farm itself. Over the years, Merle had acquired a great deal of land—land that needed to be plowed and planted and harvested. Land that this past spring had barely produced a saleable crop and that now in the fall was nowhere near ready to be planted. After her husband’s death, Pleasant had turned the management of the farm over to her brother-in-law. Hilda’s husband, Moses, was a shy, quiet man—nothing like Hilda. But he had a head for business and managed the farm as well as his dry goods store with an expertise that set Pleasant’s mind at ease. Still, he would not make a decision without first consulting with her and Rolf. For as she explained to Jeremiah, the farm was Rolf’s future, in spite of his father’s doubts that he would ever amount to anything as a farmer or businessman. She worried about Rolf. Merle’s constant badgering of the boy had taken its toll, and of all the children, he had been the hardest to bring closer. Whenever she tried to show her appreciation for some chore he had done without being asked or commented on his high marks in school, his dark eyes flickered with doubt and distrust.

It had been a week since Jeremiah Troyer had stopped at the bakery and asked to interview the boy for a job in his ice cream shop and Pleasant had been unable to forget the look that had crossed Rolf’s face when she’d turned down the offer. Just before he’d lowered his eyes to study his bare feet, she had seen a look of such disappointment come over his features and there had been a flicker of something else. For one instant he had looked so much like his father.

Memories of the rage that had sometimes hardened Merle’s gaze came to mind now as Pleasant rolled out dough and plaited it into braids for the egg bread she was making. She paused, her flour-covered hands frozen for an instant as the thought hit her. What if Jeremiah had been right? What if Rolf turned out to be as bitter and resentful as his father had been? Could such things be passed from father to son like the color of eyes or hair? Or was it possible that circumstances might guide the boy in that direction? Certainly Merle’s resentment had begun early in life and in spite of his success in business and the love he had shared with his first wife, he had remained until the day of his death a man who looked at the world with hostility and ill will.

“Well, not Rolf,” Pleasant huffed as she returned to her task. “Not my son.”

But how to set the boy on a different path?

She wiped her forehead with the back of one hand and blew out a breath of weariness and frustration. How, indeed, heavenly Father?

She walked to the open back door of the bakery, hoping to catch a breeze before she had to face the hot ovens again. Next door she saw Jeremiah Troyer replacing a wooden column that supported the extended roof of his shop. She thought about the Sunday when he had easily lifted two of the heavy wooden benches used for church services—one under each arm. She continued to observe him as he fitted the column in place and anchored it, drawing one long nail after another from between his lips and pounding them in until the column was locked in place.

Who would teach Rolf such things? Her father? Perhaps. But he was getting on in years. He tended to leave the heavy chores to the carpenter, Josef Bontrager, who was always willing to help because it gave him an excuse to see Greta. She thought about the way Jeremiah’s ready smile and easy laughter were so different from Merle’s personality. Might it be enough to simply expose Rolf to this different breed of man? To let him see that not all men were like his father had been? That there were other ways he might decide to go?

Without realizing that she had done so, Pleasant opened the screen door and stepped outside. Jeremiah gave the porch post a final test for steadiness and turned when he heard the squeak of the screen door. The hammer he’d used in one hand, he raised the other hand to his hat and tipped his head in her direction. “Pleasant.” He acknowledged her with a quizzical smile as he squinted against the morning sun. “Was there something I could do for you?”

Flustered to find herself outside and engaged in this exchange with him, Pleasant reverted to her usual defense. She thinned her lips and frowned. “Not at all,” she replied. “The ovens give off such heat. I just needed a breath of fresh air.”

Jeremiah nodded and turned back to his work. He set down the hammer and picked up a broom. Meticulously, he rounded up the wood shavings and sawdust left from shaping the porch column to match its mate.

“You know if you’d like, Rolf could paint that column for you when he comes home from school later,” she called.

Jeremiah stacked his hands on the tip of the broom handle and leaned his chin on them as he studied her. “That would be appreciated,” he said.

Pleasant nodded and turned to go back inside the bakery’s kitchen. It’s a start, she thought.

“I could still use an assistant,” Jeremiah called and her step faltered. “Maybe we could see how painting the porch post works out and then …”

“My offer is simply that of a neighbor wishing to help another neighbor,” Pleasant said stiffly.

“Got that part,” Jeremiah said, moving closer, twirling the broom handle through his fingers and grinning. “But you’ll soon learn that I don’t give up easily, Pleasant.”

It was the second time he had used her given name that morning. It was as if he were testing her. She smiled sweetly, the way she had seen her half sister Greta smile when she was determined to have her way. “And in time you will learn, Herr Troyer, that I do not make decisions lightly and I will always do what I think is best for my children.”

She turned to leave but realized that he was propping the broom against the wall and intended to follow her inside.

“How’s the cone recipe coming?” he asked as he held the door for her and then followed her into the kitchen.

“I expect to have some samples for you to try by the end of the week,” she said. “They would best be tested with ice cream since the flavors will have to mingle.”

He nodded and took a seat on one of the stools that Gunther kept in the kitchen.

Make yourself at home, she thought, exasperated by his assumption that his presence was welcome.

“How about this? You let me know as soon as you have something that you think might work and I’ll make up three different flavors so we can try the various combinations. We can have a tasting party.”

She opened her mouth to refuse, but then thought, Why not? It would be a special treat for the children. “All right,” she replied, placing the braided egg loaves on pans.