Полная версия

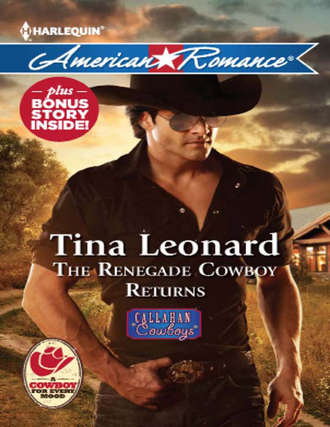

The Renegade Cowboy Returns

He scratched the back of his neck, thinking that Leslie hadn’t managed to spare him. But maybe he didn’t deserve any sparing. “That’s all true, pretty much, though I do have two nickels.”

Cat didn’t seem impressed. “How long am I staying here?”

He shrugged. “I guess until school starts. You like your school, right?”

“I don’t know. The kids are weird.”

Gage sighed, thinking his daughter wasn’t doing a whole lot to fit in. In that, she was like him. “You want to know about this side of the family?”

“No,” Cat stated. “I’m not going to see you again after August. I’ll never meet your family. So I don’t care.”

It was true she wouldn’t meet the family. Gage generally stayed as far away from them as he could, leaving his sister and two brothers to run Phillips, Inc., in Hell’s Colony. He wasn’t cut out for politics, or family debates. “Well, it’ll make good storytelling, since we’re both bored.”

“I could go back in and talk to the Weirdos,” Cat offered. “Except I think I heard them talking about whipping up some dinner. The old lady mentioned something about dog legs and bat wool.” She shivered.

Gage laughed. “Sounds delicious.”

“I think you should throw them out.”

“That old lady, Mrs. Myers, gave you a pair of pretty birds. Cut her a break.”

Cat sighed. “I guess that was kinda cool. Anyway, I guess you want to bore me to death with your family skeletons. Mom says you’ve got such a closetful of ’em that Dracula would be impressed.”

Jeez, Leslie. “Okay, there’s your uncle Shaman.”

“Weird name.”

Gage decided weird was one of his daughter’s favorite words. “Shaman’s two years younger than me. He’s in the military, been in since college. In high school, the girls were crazy for him because he was definitely anti-authority, anti-establishment. In other words, he was a hell-raiser—although, strangely, he graduated valedictorian.” Gage laughed, still proud of his brother. “He’s probably my favorite sibling, but I haven’t seen him in years.”

“Because you’re on the road all the time, shifting from place to place.” Cat nodded, obviously repeating her mother’s side of the story.

“Then there’s Kendall. She’s two years younger than Shaman, and four years younger than me. Kendall is twins with Xavier. He goes by Xav.”

“They’re the ones who run the family business. Mom says they’ve got more money than King Midas, and that you got kicked out of the business because you were too bone-idle to help run it.” Cat looked at her father. “Why are you so lazy?”

“Because,” Gage said, ruffling his daughter’s hair—the side of her head that had hair, “I’m an itinerant cowboy, and that’s what we do. Let’s go check on Mrs. and Miss Myers. They might need help.”

Cat padded after him into the kitchen, her black-checked tennis shoes not making a sound.

“We’re going into town to get some ice cream,” he said. “Anybody want to join us? What is that?” he asked, staring at the two-tier confection on the kitchen counter that Mrs. Myers was frosting.

“This is dessert for people who eat their dinner and put away their dishes,” Moira said. “It’s coconut cake. My own mother’s recipe.”

“It smells wonderful.” Gage’s mouth began watering.

“It is.” Chelsea took the spreading knife from her mother and handed it to Cat. “You finish the frosting, Cat.”

The teen looked at the cake uncertainly. “I can’t. I don’t know how. It’s just a stupid cake, anyway.” She tried to hand the spreader back to Moira, who shook her head.

“There’s nothing that can’t be fixed, love,” the woman said. “Go on, nice and easy. And when you’re finished, please sprinkle these coconut bits on top.”

Moira turned away to do something at the sink. Chelsea peered into the fridge, monitoring the contents, not paying any attention to Cat. Cat looked at her father, a question in her big brown eyes. He nodded, and she took a deep breath, reaching out to place some frosting on the cake.

“It tore,” she said. “I can’t do this! It’s a stupid—”

Moira took her hand, gently showing her how to spread the frosting in a smooth, gliding motion that didn’t disturb the cake. Then she turned back to the sink, and after a moment, Cat tried again.

The frosting went on like it was supposed to, and Cat applied herself more diligently to the task, silent for the moment. Gage’s breath released from his chest, though he hadn’t realized he’d been holding it.

“Gage,” Chelsea said, “we’re going to need some things from the grocery, now that there are four of us. I’ll make a list, if you’d like to do the shopping.”

“I can do that,” he agreed, glad to be given an assignment. “I’ll pay for the groceries, if you’re going to be kind enough to fix meals.”

“We’re going to have pot roast and…” She glanced at Gage. “I forgot you’re a vegetarian. You’ll have to pick up the veggies and things you like to eat.”

Cat stared at her father. “You’re a vegetarian? That’s weird.”

Gage shook his head, having heard weird one too many times today. “I’ll take care of the groceries, Chelsea. Thank you both for cooking for us. Come with me, Cat. You and I will start clearing out the barn.”

“I don’t want to—” she said, putting down the spreader and following her father.

“I know,” Gage said. “It’s weird. But everybody works if they’re lucky enough to have a job, and we do. So you can help me clear the barn. I need to sketch a new structure, and then decide if this is the right location for a barn, according to Jonas’s new plans, and then we’ll talk to a few architects, let them draw up some things for the big man. How does that sound?”

“Terrible. Boring.” Cat followed her father out, almost at his heels.

Moira smiled at Chelsea. “Nothing a little cake and sweet tea won’t cure.”

Chelsea nodded. She hoped so, anyway. “I’m going to make a list for Gage, and then go write for a little while. Will you be all right?”

“I’m happy as a lark,” Moira replied. “I’m going to play with this new phone Fiona talked me into. She’s been texting me for the past hour, but I haven’t had time to look.” Moira beamed. “I want to see what my old next-door neighbor is up to now.”

“Probably something weird, to use Cat’s word.”

Moira laughed and Chelsea went upstairs to ponder her heroine’s dilemma. Life for Bronwyn Sang wasn’t getting any better. Bronwyn had been dangling off the edge of the cliff for three months. Chelsea’s book was due to her editor in one month.

She’d written only ten chapters.

“I’m in deep water here,” she told Bronwyn. “I’m starting to think your problem is that you’re passive. If you had an ounce of kick-ass in you, you wouldn’t be dangling. He’d be dangling.”

She sighed, and decided to write the grocery list first. That was something she could handle, a small little list that—

Chelsea stopped fiddling with her pen, her attention caught by Gage and Cat outside her window.

He was showing her how to aim his gun at a large can he’d placed on an old moldy hay bale near the ramshackle barn. “Argh,” Chelsea said. “It isn’t any of my business. You’re my business,” she told Bronwyn, turning back to her book, which was going nowhere fast. “If you were anything like Tempest, you wouldn’t just be hanging around—”

Tempest. Now there was a woman who had decided she wasn’t going to be a doormat to anyone, probably including evil villains. The photo of Zola as a child and the adult renderings of Tempest had been vastly different. Only the eyes had looked the same, eyes that had seen a lot in life.

Tempest, Chelsea wrote, tapping on the screen just under where Bronwyn dangled, awaiting certain death from the killer in book three of the Sang P.I. mysteries, is a woman who knows what she wants. She walked away from her small town and she never looked back, making herself into one of the most sought-after women in the world. She is beautiful and independent, and men throw themselves at her feet. But she is in charge of her own destiny, so she doesn’t need a man to save her.

I wish I could meet Tempest.

The crack of a gun outside made Chelsea jump. She peered out at Gage and Cat. Cat was receiving a high five from her father, and the can had been pretty much obliterated.

“Really!” Chelsea muttered. There had to be another way to bond with one’s long-lost daughter. Grinding her teeth, she put on her headphones and went back to Detective Sang.

* * *

“GREAT JOB.” GAGE retrieved the can and set it back up on the bale. “Looks like you’ve got sharp eyesight and good hand-to-eye coordination. You’d probably like archery, too.”

“I don’t know,” Cat said, looking like Eeyore. He felt sorry for his daughter with her half-shaved head. She’d be such a pretty girl without the angst written all over her. A bit of anger boiled up inside him at his ex-wife. It had been simmering ever since he’d found out Leslie had kept Cat a secret. Anger, he knew, did nothing, didn’t help anything. He preferred to blot those emotions, any emotion, really. Seesawing emotions blinded one to what needed to be done in life.

But his daughter shouldn’t look so despondent, even if she was a newly minted teen. “Hey, what do you say we go for a horse ride?”

“I don’t know how to ride a horse.”

“You live in Laredo. There are plenty of horses.”

“I know, but Mom’s afraid of them. So I never learned to ride.” Cat shrugged thin shoulders. “They’re just stinky animals, anyway.”

He remembered Leslie saying something like that. “Okay, you don’t have to ride.”

Cat looked around at the vast, empty acreage. “So I’m stuck here for the rest of the summer? With no friends? Surely there’s somebody besides the two oddballs in there.” She flipped her hand toward the house, and Gage sighed.

“First, we don’t know that they’re oddballs. Anyway, the truth about meeting people is that usually it’s best to give folks a chance. If you talk to them twenty times and you still don’t like them, then that’s just the way it is. But sometimes you get a wrong first impression. It’s easy to do.”

“Yeah.” Cat didn’t sound as if she thought she’d like Moira and Chelsea on closer inspection. “So, where’s your family you were talking about? Mom says you’re the loner, and that none of them really like you.”

Gage put his gun away and ran a hand over his daughter’s long side of hair. “Here’s the deal. I know you love your mom. And that’s a good thing. But let me suggest that Leslie hasn’t seen me in a great many years, so she doesn’t know me. And I think you’re old enough to make your own decisions about things.” He shrugged. “I’m not saying whatever your mom said about me and my family isn’t true, I’m just saying it may not all be true. And you owe it to yourself to make your own mind up.”

Cat took that in for a minute. “Okay.”

“Good.” Gage thought his daughter probably wasn’t a bad kid, probably just confused and somehow out of place. The mouth likely got her into trouble, and the air of I-don’t-give-a-damn, when she clearly very much did.

I remember that stage. It sucked.

“So, anyway, I guess I’ll never meet my aunt and uncles,” Cat said morosely.

Gage let out a breath and went to sit on the bale of hay. “Never is a long time.”

“Yeah.” She shrugged, and sat on the ground cross-legged. “Mom called your sister.”

Gage’s jaw clenched. “Did she?”

“Yeah. She told her about me. Mom said she was hoping maybe what’s-her-name would know where you were this summer.” Cat looked at him. “Mom said your sister didn’t know, but gave her your cell phone number and then said some rude things about her.”

Gage winced. “Don’t worry about that. It has nothing to do with you, Cat. Kendall’s mouth runs away with her at times.”

“I was hoping for a normal family,” Cat said, her tone wistful.

“We all do, sweetie. ‘Normal family’ is pretty much a fairy tale.”

“Brittany Collins goes to my school, and she has a normal family,” Cat insisted.

“That’s good,” Gage said, thinking that his daughter was very young, very confused. It was only to be expected that she might look around her and see girls whose lives she’d like to emulate. “We better get going to buy those groceries. And you wanted ice cream.”

“That sounds boring,” Cat said, and Gage laughed.

“Boring’s not so bad.”

“Maybe not,” Cat said doubtfully. “Maybe you should ask the Weirdos again if they want to go with us.”

Gage glanced at his daughter. “You wouldn’t mind?”

She shrugged. “We’ll look like a freak show, but no one knows me here, I guess. And the old lady was nice to bring me some birds. I really like them. Mom won’t let me have pets—she says they’re dirty. She’d flip out over birds, I bet.” Cat sounded cheered by that. “And that lady you stare at all the time—what’s her name?”

“Chelsea,” Gage said, “and I do not stare at her.”

“Yeah. You do. Kind of like my mom stares at Larry.” Cat shuddered. “Larry is such a loser. I don’t know why she stares at him. He looks like a frog.” She glanced at her father. “You don’t look like a frog.”

“Thanks.” Gage smiled. “You want to go inside and invite the ladies?”

“Do I have to?”

“Your idea.”

“Ugh.” Cat walked into the house to the kitchen, where she knew she’d at least find the old lady who loved pink clothes. “Hey, Dad’s taking me for ice cream. He said it would be nice if you and your daughter came along to keep us company. He says we don’t know what to say to each other, and that it’s pretty awkward.”

Moira glanced up from her cookbook and smiled at Cat. “What a bonny idea. As a matter of fact, I was thinking you and I should make a trip to the library one afternoon.”

“What for?” Cat asked suspiciously.

“As we were discussing Macbeth,” the old lady began, and Cat shut that down in a hurry.

“You were discussing Macbeth. I just didn’t want you giving me any fried newt eyes.”

Moira smiled and tied on her rain cap.

“What’s that for? It’s not raining.”

“You’re right. It’s not,” Moira said, tying the pink polka-dotted plastic securely on her head. “Could you be a love and run upstairs and get my daughter, please? Knock first, and only go in if she says you may. She might be writing.”

“Something awful, I’m sure,” Cat said, her tone depressed and certain that whatever Chelsea was writing, it had to be worse than a third-grader’s school paper. She banged on the door.

Chelsea opened it, smiling when she saw Cat. Cat sniffed to let her know she didn’t like her. “Dad says you and your mother have to come eat ice cream with us. He says he needs you because we don’t like each other very much. Your mom’s putting on her hair thing, and she looks kind of weird, but she’s going to take me to the library someday, so that’ll be a real drag.”

Chelsea nodded. “Ice cream sounds wonderful.”

Cat looked past Chelsea into her room. “You’re probably not a very good writer.”

“Um—”

“I bet nobody would ever buy your books.” Cat looked up at her. “Anyway, you should be a schoolteacher or something.”

“Why?” Chelsea asked, following her down the stairs.

“You look like one,” Cat said, making it sound as if it wasn’t good to look like a teacher.

“Thank you,” Chelsea said. “My mother was a schoolteacher. I always admired her.” A schoolteacher! No one probably ever told Tempest she looked like that.

Chelsea wondered if Gage thought she looked like a schoolteacher. She patted her hair, which had a tendency to get wild and unruly when she was writing, from constantly shoving a hand through her bangs when she was deep in thought.

“I’ll sit in front,” Cat said, “next to my father.”

“Perfect. This is a nice truck, Gage,” Chelsea said.

“I just bought it.” He turned to smile at her, and Chelsea noticed her stomach give a little flip. He had such nice white teeth in his big smile, and his dark eyes seemed so full of life that it was hard not to smile back.

She saw Cat glowering at her, and wiped the answering smile off her own face. “I saw you shooting, Cat. Was it fun?”

“No,” Cat said.

“Do you shoot, Chelsea?” Gage asked.

“Not unless I have to.”

“I do,” Moira said. “I can bag a quail at fifty paces.”

“She can,” Chelsea said. “Many a time we ate something Mum brought home.”

“Eye of newt,” Cat said.

“Maybe,” Chelsea said. “In my home, we ate what was on our plates, said thank-you, excused ourselves and cleared the table. No questions asked.”

Cat turned to look at Moira. “Are you going to make me do all that?”

Moira nodded. “Of course, lamb. Otherwise, I don’t cook.”

“Jeez,” Cat said. “This is worse than prison.”

“Cat,” Gage said, his tone warning.

Chelsea looked out the window, amazed by the lack of cars on the road into town. “Tempest is like an old postcard that never changed.”

“I like that,” Gage said. “I like that it seems preserved in time.”

“I do, too.” Chelsea jumped when Gage’s gaze caught her eyes in the mirror above the dash.

“It looks boring,” Cat said, her nose pressed to the window as she looked out at the farmland they passed. Cows and horses and an occasional llama dotted the dry landscape. “I’d be embarrassed for my friends to know I was stuck out in the middle of the desert. I’ll probably get stung by a scorpion.”

“That reminds me—by chance did your mom send you with a pair of boots?” Gage asked, glancing at her black-and-white-checked tennis shoes.

Cat shrugged. “I’ve never had boots. I don’t need any, because I’m not going to be an itin…itin—”

“Itinerant,” Gage supplied.

“Cowgirl,” she finished, convinced she had life all figured out.

Chelsea’s gaze once again caught Gage’s in the mirror. He appeared a little chagrined by his daughter’s attitude. Chelsea told herself that his and Cat’s problems had nothing to do with her. In fact, she should be at home writing, giving Bronwyn a chance to figure her way out of her mess.

It was so much more exciting to wonder about Tempest, and how she might handle the pitfall Bronwyn had landed in.

I’m not good at pitfalls. I don’t like guns. I don’t like scary stuff. How did I ever wind up writing mysteries?

Maybe I write mysteries because I love puzzles. And I crave adventure—just like Cat.

She looked at Gage, thinking he was pretty much the call of the wild in real life—but she wasn’t adventurous Tempest. Except for her and her mother’s excursion to America, adventure came to her only on the safe pages of her novels. She would never have the courage to walk away from her life and be someone she wasn’t. “Gage,” Chelsea said suddenly, telling herself it was folly to get involved, “do you know when the nearest rodeo is?”

“Santa Fe. This weekend.” He looked at her. “The four of us could go, if you’d want to see one. Moira, have you been to a rodeo?”

“Not a one, and I’d love to,” Moira said. She shot her daughter a glance of approval, then looked at Cat.

“I’ve attended one, and I’d really like to go again,” Chelsea said. And give Cat a chance to see boot-wearing cowgirls and cowboys outside her hometown, doing their jobs.

“Great. We’ll go,” Gage said.

“Sounds boring,” Cat said.

Chelsea smiled. “We’ll see.”

* * *

AFTER A QUICK GROCERY RUN, they ran into Blanche the waitress at Shinny’s Ice Cream Shoppe. Introductions were made, and when Moira went off to look at the photographs on the walls, and Cat and her dad were engaged in some getting-to-know-you chitchat, Chelsea wandered over to the gregarious waitress. “What flavor?”

Blanche smiled. “Peppermint. My favorite. You?”

“I think peach.” Chelsea liked Blanche. In fact, she liked much of what she’d seen around the town of Tempest so far. Which brought up the name that had been stoking her curiosity, even making her wonder if she’d plotted her heroine wrong in her current book. “So tell me more about Tempest.”

“You’re not asking about the town, are you?” Blanche gave her a smile that reached her big eyes behind red-and-blue-swirled glasses frames.

“I want to hear about that, too. But I have to admit you caught my interest with the tale about Tempest.”

“C’mon.” Blanche waved her over to a black-and-white photograph on the wall. “This is Zola when she was just a wee thing.”

Chelsea blinked. “She seems so thin.”

“Yeah. Well, it wasn’t for lack of eating, I don’t think. Her mom used to send her down every day to this very ice cream shop. My husband, Shinny, over there—” she pointed to a friendly-looking, balding man who was sweeping up “—he owns this shop. He gives ice cream out to the kids, especially the ones he knows got folks who can’t afford it. Zola was on his list of kids who always got a double scoop, or a milkshake if he could talk her into it. Chocolate,” Blanche said with a smile, “in case you were going to ask. Shinny’s special.”

Chelsea moved to a photo of Tempest’s most famous citizen standing in a field, looking at the camera with wide eyes. Her bare feet looked dirty and her overalls not much better. “Did she have a high school sweetheart?”

“No.” Blanche pointed to a football team photo with a pretty brunette standing in a shiny uniform beside the team. “Maggie Sweet was the girl the guys went for. Not a skinny, brown-headed sparrow like Zola. Funny thing is, when she grew up and left this town behind to become Tempest, men pursued her like mad. She went through men like candy, and I don’t think she was serious about a one of them. She had one serious guy, some minor royal from Scotland, I think. Anyway, she found out he had a lady on the side, and left him just like she’d left this town.” Blanche smiled, remembering. “We were all afraid she’d be heartbroken, but Tempest said it was his loss.”

“How do you know all this?” Chelsea had to know more. “I thought she went away and never looked back.”

“She used to call back here from time to time. It’s just been the last year or two we haven’t heard a peep from her. About to send a delegation over to check on her.” Blanche didn’t look convinced that that would have much impact. “We still love her here. She’ll always be Zola to us.”

She’d always be that dirty little girl in the threadbare clothes, Chelsea thought. No wonder she wanted to make herself into Tempest. Chelsea could understand wanting to get away from her old life. It would be fun to be a heroine in a book for a day. Not my heroine. She’s been dangling so long she’s afraid she’ll never get off that cliffside.

“Ready to go?” Gage asked Chelsea, smiling a greeting at Blanche. “I’ve got to get Cat home. She says she’s tired after her big day of traveling. If you want me to come back later and pick you up—”

“I’m good. Thanks.” Chelsea smiled at the woman in turn as she got up from the swivel seat she’d settled on while they’d been chatting. “I enjoyed the town history lesson, Blanche. Thank you.”

Blanche waved a hand, reached out to pat a grumpy-looking Cat. “You come back anytime, sugar. Free ice cream for pretty little girls.” She smiled at her. “You look so much like your daddy.”

Gage appeared pleased. “Thanks, Blanche. I take that as a real fine compliment.”

Cat glanced up at him, surprised. “You do?”

He nodded. “Sure I do.”

Cat didn’t seem to know what to think about that. She remained silent, following him as he went to escort Moira to the truck. Chelsea went out behind them, watching Gage interact with his daughter, thinking that for a man who’d just found out he was a dad, he was handling it very well.

* * *

“THANKS,” GAGE SAID as he walked the women to the front door. Moira and Cat went on inside to check on the birds, which Cat had named Mo and Curly—he guessed Larry hadn’t been her favorite of the Three Stooges—so Gage grabbed the chance to tell Chelsea exactly how he felt.

Damn grateful.

“For what?” She looked at him, surprised.

He shrugged, not certain how to express what he wanted to say. “Helping Cat make the transition. And me.”