Полная версия

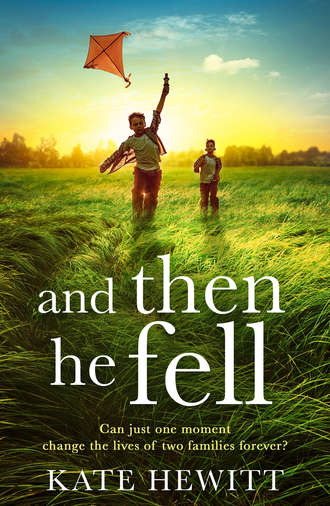

When He Fell

The director at the preschool advised testing, and so I took him to various doctors, all of whom flirted with different diagnoses. They ruled out autism or anything ‘on the spectrum’, as has become the parlance. I was relieved as well as a tiny bit disappointed. At that point I craved a diagnosis, an answer. I wanted this to be a problem I could fix, or at least treat.

They moved on to other conditions: social anxiety disorder. Social phobia. Depressive disorder. Nothing was definitive. No one offered us anything besides more therapy, possible pills. None of it really worked.

Lewis was, although he tried to hide it, exasperated with me. “He’s just a quiet kid, Jo,” he said more than once. “Let him be. He’ll come out of it when he’s ready.”

But Josh wasn’t just a quiet kid. He wasn’t just shy; he was, as one doctor had said, selectively mute. He didn’t speak for the entire first year in preschool; not one word to anyone, not even to us at home. Kids tried with him at first, offering a toy, touching his shoulder in a game of tag. He never responded, except to shy away or duck his head. Eventually the other kids saw he was different and they stayed away. Their mothers didn’t invite him to their children’s birthday parties, even when there were whole-class invitations. Kids thought he was weird, and he was weird.

But we’ve progressed a long way from those dark days, since he’s been at Burgdorf. I’d picked the school particularly, because it catered to ‘the whole child’ and was, on the brochure, ‘a place for positivity’. Lewis rolls his eyes at that kind of language and I suppose I do too, a little, but I still feel it’s what Josh needs. Kids at Burgdorf have a lot more freedom to express themselves—or not, as Josh’s case may be. They don’t have to conform to a standard, and since Josh can’t and won’t, it’s the perfect—or at least the best—place for him. In kindergarten he started speaking again; in first grade he even made a friend. Ben Reese. The two have been best friends for nearly three years. Josh’s first and only friend, and I am as proud as if I managed the whole thing myself.

In reality I’ve only met Ben’s mother Maddie a couple of times; I’ve only seen Ben a little more than that. When they have play dates—an expression I loathe and yet accept—Lewis usually takes them out while I am at work.

Now Josh and I ride home on the subway, all the way from midtown to Ninety-Sixth Street, and he doesn’t speak the whole way. I am not bothered; in fact I am scrolling through some emails on my phone. When we pull out of the Eighty-Sixth Street station Josh rests his head briefly against my arm.

I touch his hair lightly; his eyes are closed. “Are you tired, Josh?” I ask as I delete an email from my phone. He doesn’t answer, and I decide he is.

We arrive home fifteen minutes later and Josh disappears into his room, as he often does, usually to read one of his Lego or nonfiction fact books. He’s insatiable when it comes to trivia; most of our conversations involve Josh reciting all he knows about some specialized subject. Did you know earthworms can live for up to eight years? But they die if their skin is dry. They have nine hearts.

I cannot retain the trivia, although I do try to listen to Josh and absorb it. I enjoy the evidence of his passion, even if it is simply for a collection of forgotten facts.

His other passion is Lego, although he’s never actually built anything with the blocks. He just likes studying the designs in the Lego books we’ve bought him.

While he’s in his room I make him a snack of dried fruit and nuts and pour a glass of water, the healthy alternative to cookies and milk. Lewis rolls his eyes at my insistence on things like limited screen time and no sugar or additives; he grew up on Twinkies and endless TV. But this is the plight of the modern mother; if I didn’t do these things I would be judged. Condemned. Add the fact that I am a dentist and a mother in Manhattan, and it all becomes exponentially more intense.

Lewis comes home as I am making dinner, a healthy meal of brown rice and low-fat chicken strips seasoned with paprika. I’m not very good at cooking, not like Lewis, who can throw together a bunch of ingredients with careless ease and emerge with something that tastes delicious. I follow recipes to the millimeter; it’s how I’ve always lived my life. Lewis will laugh as I level off a teaspoon, eyeing its flat surface like a nuclear physicist measuring plutonium. He never measures anything, and somehow it all works out for him.

“How was work?” he asks as he comes in the door. He shrugs off his scuffed leather jacket and rummages in the fridge for a beer. As usual when I see him I feel my insides lurch with that intense mix of love and trepidation that I’ve felt since the moment Lewis laid eyes on me at a party when I was a grad student and he worked as a maintenance man for an apartment building in Queens.

I never thought he’d be interested in someone like me. Someone who was tall and lanky with the awkwardness of a giraffe rather than the grace of a gazelle. I’d sat squeezed on a sofa at that party, a plastic cup of cheap wine clutched in my hands, and wondered why I’d come. I’ve never been good at parties; small talk has always defeated me. But I was in my first year at Columbia’s College of Dental Medicine, and I was determined to make friends.

Lewis was the kind of guy who was so inherently comfortable in his own skin that you couldn’t help but feel jealous. You wanted to be like him, or if you were a woman, you wanted to be with him. I wanted both.

When he plopped himself down on the sofa next to me, elbowing someone else out of the way, and then actually talked to me, I was incredulous. I couldn’t believe this charming man with the curly dark hair and the liquid brown eyes, the workman’s physique and the big, capable hands, was interested in me.

He asked me to dance. When we stood up I realized, to my complete mortification, that I was a good two inches taller than he was. I slouched towards the cleared space that served as a dance floor; Lewis rested his hands on my hips, unconcerned, while I contorted my body to somehow seem shorter than he was. We danced for two songs before Lewis offered to get me another drink. I accepted in the vain hope that alcohol might strip away a few of my inhibitions.

He spent the entire evening with me. I don’t remember what I said; I babbled about wanting to be a dentist and when Lewis opened his mouth to teasingly show me his gold crown I laughed in a high, whinnying way, like a horse. I was so incredibly nervous; my hands were sweaty around my plastic cup. I was afraid he’d leave me alone, and yet I almost wanted him to, was desperate for him to, because being with him was so intense, so invigorating. By eleven I was exhausted.

Lewis walked me to the subway station, and asked for my phone number before I went down the steps. I remember scrabbling in my bag for it, because I hadn’t actually memorized my own number. I remember asking for his, shyly, blushing, and he’d rattled it off with a grin. I remember almost blurting why are you interested in me before I thankfully thought better of it. And then I half-floated, half-stumbled home, caught between euphoria and terror that I might see him again.

“Where’s Josh?” Lewis asks as he pops the top on his beer and raises the bottle to his lips.

“In his room, as usual. You know how he is.” I speak lightly, as if in doing so I can dismiss the years of worry, of terror, of doctors and diagnoses, and make everything seem normal. It is normal, for Josh; I know I need to accept who he is, and who he isn’t. And I have accepted it, for the most part. It is only occasionally that I wonder if things are truly okay, or wish that they were different.

Lewis wanders over to the TV and flips it on before flopping onto the couch. I watch him sprawled there, torn between reminding him of our no screen time rule during weekdays, at least when Josh is awake, and just watching him, my heart suffused with love.

Lewis must sense my stare for he glances up from the TV, smiling slightly as he raises his eyebrows. “Come here,” he says, and I leave the chicken hissing and spitting on the stovetop and walk towards him. He holds out his arms, and I snuggle into him as best as I can; I am all awkward angles and elbows, but somehow when Lewis puts his arms around me, I soften. I fit.

He strokes my hair absently as he watches the news and I close my eyes and savor the moment until I smell the chicken starting to burn and I rise reluctantly from the sofa. I turn the chicken to simmer and start to set the table.

I call Josh, and he comes into the dining alcove, its one window overlooking the concrete courtyard behind our building. We live in a classic six on Central Park West, in a shabby building that has the benefit of a doorman and a nice address. The lobby is all peeling plasterwork and scuffed marble, and the residents tend to be people who have lived there forever or, like us, saved every last penny to buy real estate in Manhattan.

I dole out the chicken and rice while Lewis gets another beer and Josh sits at the table, his head bowed. I finally notice that something might be wrong.

“Josh?” I ask, pitching my voice light because I know I tend to panic. “You okay?”

He nods, his head still lowered, his dark, silky hair falling in front of his face. Lewis glances at him, frowning slightly, but he doesn’t press. Lewis is of the old-school belief that you let kids fall and scrape their knees so they can get up again, bloody and proud; you let them be bullied so they learn to be tough. Yet he is also the more involved parent, doing the school run and being at home in the afternoons, even if his philosophy is to be uninvolved. I, for better or for worse, am the opposite.

Lewis starts talking about a new piece he’s making, a set of built-in bookcases for some Park Avenue family. For the last ten years he’s had his own woodworking business up in Harlem.

I listen and make interested noises, ask a few relevant questions. I do all the right things, even as I glance again at Josh and start to feel worried.

“Hey, Josh.” I touch his head lightly, the tips of my fingers brushing his hair. “School okay?”

“Yeah.” He toys with his fork, pushing rice around on his plate, and then arranging the grains in a pattern. “It was fine.”

“How did your history project go?” He’d brought in a poster he’d made on the American Revolution; Lewis and I had both helped with it, all of us squealing in disgust over the little-known fact that George Washington’s false teeth were not made of wood, as many believed, but rather of human teeth he’d bought from his slaves. Josh had been particularly revolted by the thought of having other people’s teeth in your mouth, never mind the injustice of them belonging to Washington’s slaves.

“I didn’t get to present it,” Josh says. His head is still bent as he focuses on arranging the grains of rice into a perfect square. “Tomorrow, maybe.” He sucks in a breath and lets it out slowly, which has always been his signal that he is done talking.

So I force myself to let it go. To stay relaxed, because I know I worry too much and I need to trust that if something is wrong, Josh will let me know. Even if he hasn’t before.

After dinner Lewis clears the dishes and Josh retreats to his room. I frown at the closed door, debating whether to go in. I could suggest we read together, as we’ve done some evenings. It was my idea and Josh agreed reluctantly, but I think he likes the Narnia books I suggested. He doesn’t protest, anyway, when I get one out and sit by his bed to read it aloud.

But it’s still early, and I have a mountain of paperwork to get through. I’ll ask again at bedtime, I decide, and read to him then. Maybe while we’re reading he’ll talk a little more, open up about whatever is bothering him. And really, what can it be? He’s only nine, after all. Maybe Mrs. Rollins scolded him, or someone pushed him in line. The traumas of an elementary education.

I am still standing there, staring at the door, as Lewis comes up to me and places a hand on my shoulder. “Don’t worry, Jo,” he says softly, and I lean back against his chest as his arm encircles me.

“How did you know I was worrying?” I ask, and Lewis presseds his thumb to the middle of my forehead.

“You had your little worry dent going on,” he says, and I manage a laugh.

“Total giveaway,” I agree and I rest there for a moment, savoring Lewis’s embrace and letting myself believe that everything really is okay. The reassurance soaks into me, allows me to relax.

We’ve worked so hard for this, the three of us. We’ve put the difficult times behind us, the tragedy and fear and the dreaded silence. Even though life sometimes feels like walking on a tightrope, everything teetering, I choose to believe we’re steady now. We’re solid.

Lewis cleans up the kitchen while I do paperwork, and Josh stays in his room until bedtime. At eight-thirty I knock on his door and push it open, my heart lurching a little when I see him lying curled up on his bed, his knees tucked up to his chest.

“Josh?” I move closer, and then perch on the edge of his bed. “Josh. Honey. Is everything okay?” I should know better than to ask my son such an open-ended question. Josh deals in facts. The only way to get information from him is to ask factual yes-no questions. “Did something happen today to make you sad?” I try. “Did Mrs. Rollins yell at you?”

“No.” His voice is barely audible.

“Did you get in a fight with someone?” I think about Ben, but Josh never fights with Ben, as far as I know. They are utterly unlike each other; Ben is loud and rambunctious and hyper. I’ve wondered, on the few occasions that I’ve met him, if he has ADHD. Josh is none of those things, but somehow the friendship works. Opposites attract, I guess. Look at me and Lewis.

“No,” Josh says again, so softly. He squeezes his eyes shut and my heart flips over in fear. I can’t shake the feeling that something is really wrong, and I need to know what it is.

“Tell me,” I say quietly. “Tell me what’s wrong, Josh, and I’ll fix it for you. I promise.” As soon as the words are out of my mouth, I know they’re not quite right, that they’re a promise I can’t necessarily keep, and yet I mean them. I mean them so much.

But Josh just hugs his knees more tightly to his chest and keeps his eyes closed. He doesn’t say anything, which is not a surprise and yet still a worry. After a moment I rise from the bed and fetch his pajamas. He takes them obediently, and I rest a hand on his shoulder for a moment before I leave the room for him to change.

In the living room Lewis is sitting at the desk by the window, going over some invoices. His phone beeps with an incoming voicemail and he glances at it, frowning, before tossing it aside.

“Everything okay?” I ask.

“Yeah, just a work thing.” He gives me a quick, distracted smile.

“I’m worried about Josh.”

Lewis sighs. “I know you are, sweetheart.”

I stand behind him, resting my hands on his shoulders. “He really doesn’t seem himself, Lewis.”

“We all have bad days.” Lewis glances up at me, patting my hand before turning back to his paperwork. “He’ll be fine.”

I remain there a moment, taking comfort from Lewis’s warmth, his steadiness, his certainty that life will fall into a usual, peaceful pattern. I’m amazed at Lewis’s faith sometimes; his own childhood was tempestuous, with his mother dragging him across the country after a bitter divorce and then basically ignoring him for the next ten years while she went through several deadbeat boyfriends. Yet despite all that Lewis still possesses a seemingly unshakable faith that things will work out for us, for Josh, even when they haven’t in the past. But I don’t think about that.

I finish tidying up the kitchen and then I go back into the bedroom to say goodnight to Josh. He is already huddled under the covers, his eyes closed, his breathing even. I wonder if he is asleep—maybe he really is just tired—but then I notice how tense his shoulders are, scrunched up by his ears.

“Josh,” I say softly, and he doesn’t reply. He doesn’t even open his eyes. I decide to play along that he is asleep, just for tonight, because maybe all he needs is a little space, a little time. Maybe he did just have a bad day as Lewis said.

Gently I pull the duvet up over his shoulders and brush a kiss on his forehead, my lips barely touching his skin. I breathe in his little boy scent of soap and sweat and sunshine, my eyes closed. Then I tiptoe from the room and close the door softly, and hope that just as Lewis always believes, everything will look better in the morning.

3 MADDIE

That night in the ER Ben experiences storming, which is a term I’d never heard before, but which Dr. Stein explains to me. Storming is, in layman’s terms, when a person’s vital signs go haywire; Ben’s temperature rises and then drops, his body seizes, his heart rate is all over the place. Dr. Stein tells me this happens in ‘roughly fifteen to thirty-three percent of all TBI cases’—TBI being traumatic brain injury. I am starting to know the acronyms, and I hate them all.

When I ask Dr. Stein why this happens, he launches into a lengthy soliloquy on possible causes of storming. Maybe it’s ‘sympathetic’, and is part of the recovery process. Maybe it’s a reaction to the drugs he is receiving, or a change in dosage. Maybe it’s a neurological response to the initial trauma. Blah blah blah. I am desperate to understand, and yet this is a language I don’t speak. I want bottom lines and doctors don’t give those. They don’t deal in promises.

I stand at the door and peer at Ben through the window; the sight of his body flailing in the bed, the machines beeping faster and louder, is beyond terrifying to me, but I am coping better now, or perhaps I am simply numb. Numb and utterly exhausted, living in this terrible stasis, and I have no idea what happens next.

Lewis hasn’t called me back. I didn’t expect him to, but I am still disappointed.

At ten o’clock that night I break down and call Juliet. I need to talk to someone.

“Oh, Maddie,” she exclaims as soon as she answers the phone. “Is Ben going to be okay?”

Shock slaps me in the face. She knows. Juliet knows about Ben. How? Why? And why didn’t she call? I swallow down my own question to answer hers.

“I don’t know, Juliet. He’s in a medically-induced coma.”

“Oh, no.” She let out a muffled sob and I feel an unreasonable dart of anger, because I haven’t permitted myself to shed any tears, but she can? She has that presumption?

“How…how did you know?” I ask. And then I realize how little I know; I don’t even know how or where he fell. I’ve been too busy coping with the result to wonder about how it happened, or where, or why. And suddenly I feel like I need to know these things, that they might be important.

“I…” Juliet hesitates. “I was on playground duty.”

Burgdorf parents are required to volunteer for the school three hours a week; I usually end up stuffing envelopes or doing data entry after work, while Ben is in afterschool club. Juliet does the ‘fun’ things, the field trips and playground duty. She was there when Ben fell. Which means she knew about this for hours and hours, and yet she never even called me.

“It happened on the playground?” I finally ask, and my voice sounds scratchy, hoarse. “Did you see him? How did he fall?” I blurt the questions, needing facts.

“I didn’t see,” Juliet says quickly. “The kids were running all around, you know how it is. It all happened so fast…” She trails off, helplessly, and I close my eyes. Does it really matter if he fell off the slide or the swing? Or maybe it was the huge concrete climbing structure in Heckscher Playground in Central Park, where the kids often go for recess. Ben’s twisted his ankle or banged his knee on that thing more than once. Wherever he fell, it landed him here, fighting for his life.

“I’m so, so sorry,” Juliet says. “They rushed him to the hospital. The paramedics were so good…”

I can feel the sting of tears in my eyes, and I can’t believe that after everything that has happened, I am going to cry now. “You didn’t even call me,” I choke, and I am ashamed at how needy I sound. I’ve learned not to be needy, not to depend on anyone. A lifetime in foster care makes you an expert in self-sufficiency.

“Oh Maddie, honey, of course I wanted to,” Juliet says, her voice breaking. “But I knew Mrs. James would contact you first and I didn’t want to barge in before she could tell you the details…”

But she wasn’t there. You were. And you’re my friend. The protests lodge in my throat like stones.

“…And then with the kids… Emma had ballet exams today…” She trails off, and I know she realizes her excuses are cringingly, shamefully lame. And I don’t understand why Juliet is failing me like this, because I’ve always considered her a good friend.

I don’t have a lot of experience with friends of any kind, but I’ve known Juliet for ten years, since Ben and Emma were babies. For the last three years she has treated me to a ticket to the school’s annual charity gala, and made sure I sit at her table. She’s given me her castoff clothes even though they’re not my style at all. They’re still good quality. She’s had me over for Thanksgiving when they’re in the city and she knows I have nowhere to go. Why didn’t she call me when she knew my son was in the ER, in a coma?

“He’s going to be okay, though,” she says, and her tone is deliberately upbeat. Maybe she’s trying to mimic Burgdorf’s environment of positivity, but I feel none of it now.

“I have no idea,” I tell her flatly. “The doctor told me the next twenty-four to forty-eight hours are critical.” I pause. “As to whether he lives or dies.”

“Oh, Maddie…” Juliet’s voice is like the cry of a small animal, as if I’ve hurt her with this information, and suddenly I can’t take any more.

“I have to go,” I say abruptly, and I hang up. I walk back from the little waiting room to the doors of Ben’s room—a journey I already feel I’ve made a thousand times—and peer in the window. Ben is still restless and agitated, his body jerking spasmodically as the doctors and nurses attempt to subdue him. I can’t bear to see him like this, and yet I can’t look away either. All I can do is wait.

Wait and wonder, because as I replay the conversation with Juliet something doesn’t feel right. Juliet would call me. She’s the type of person who calls, who cares.

Why didn’t she see how Ben fell? Why didn’t she give me any details at all?

I can’t help Ben now, and so I focus on what happened. On finding out what happened. I call Juliet again. She answers after the fourth ring, her voice a little wary.

“Maddie?”

“I just want some details,” I burst out. “About how it happened. Was it on Heckscher Playground?”

“Yes…you know that’s where they go for recess when it’s nice out.”

“Where was he? On the climbing structure? Or the swings—”

“I…I’m not sure.”

“But if you were on duty,” I persist, trying to keep my voice reasonable, “you were looking. You must have some idea.”

Juliet hesitates. I can hear her breathing, and for some reason it makes me angry. “On the climbing structure,” she finally says. “I think.”

You think? I bite the words back. “Okay,” I answer, managing to keep my voice even. “Okay. Thanks.” And then I hang up.

I feel prickly with suspicion, with hurt. Juliet saw my son fall, or at least was there when it happened. She saw him taken away in an ambulance. Why didn’t she call me? I don’t understand how she could be so callous. Ballet exams.

I press my fists to my gritty eyes. I met Juliet in a mother and babies group, when Ben and Emma were both eight weeks old. I went to save my sanity, because dealing with a fussy, disgruntled baby in my box of an apartment all on my own for twelve hours a day was testing the limits of my endurance. Juliet was there, looking beatific and Botticellian, nursing her chubby, pink-skinned daughter with an ease that I was too tired to envy.