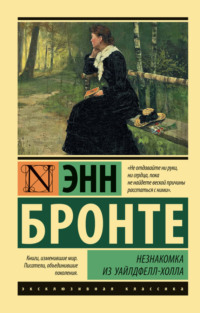

Полная версия

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

But we had not done with Mrs Graham yet.

‘I don’t take wine, Mrs Markham,’ said Mr Millward, upon the introduction of that beverage; ‘I’ll take a little of your home-brewed to anything else.’

Flattered at this compliment, my mother rang the bell, and a china jug of our best ale was presently brought, and set before the worthy gentleman who so well knew how to appreciate its excellencies.

‘Now this is the thing!’ cried he, pouring out a glass of the same in a long stream, skilfully directed from the jug to the tumbler, so as to produce much foam without spilling a drop; and, having surveyed it for a moment opposite the candle, he took a deep draught, and then smacked his lips, drew a long breath, and refilled his glass, my mother looking on with the greatest satisfaction.

‘There’s nothing like this, Mrs Markham!’ said he, ‘I always maintain that there’s nothing to compare with your home-brewed ale.’

‘I’m sure I’m glad you like it, sir. I always look after the brewing myself, as well as the cheese and the butter – I like to have things well done, while we’re about it.’

‘Quite right, Mrs Markham!’

‘But then, Mr Millward, you don’t think it wrong to take a little wine now and then – or a little spirits either?’ said my mother, as she handed a smoking tumbler of gin and water to Mrs Wilson, who affirmed that wine sat heavy on her stomach, and whose son Robert was at that moment helping himself to a pretty stiff glass of the same.

‘By no means!’ replied the oracle with a Jove-like nod; ‘these things are all blessings and mercies, if we only knew how to make use of them.’

‘But Mrs Graham doesn’t think so. You shall just hear now, what she told us the other day – I told her I’d tell you.’

And my mother favoured the company with a particular account of that lady’s mistaken ideas and conduct regarding the matter in hand, concluding with, ‘Now don’t you think it is wrong?’

‘Wrong!’ repeated the vicar, with more than common solemnity – ‘criminal, I should say – criminal! – Not only is it making a fool of the boy, but it is despising the gifts of Providence, and teaching him to trample them under his feet.’

He then entered more fully into the question, and explained at large the folly and impiety of such a proceeding. My mother heard him with profoundest reverence; and even Mrs Wilson vouchsafed to rest her tongue for a moment, and listen in silence, while she complacently sipped her gin and water. Mr Lawrence sat with his elbow on the table, carelessly playing with his half-empty wine-glass, and covertly smiling to himself.

‘But don’t you think, Mr Millward,’ suggested he, when at length that gentleman paused in his discourse, ‘that when a child may be naturally prone to intemperance – by the fault of its parents or ancestors, for instance – some precautions are advisable?’ (Now it was generally believed that Mr Lawrence’s father had shortened his days by intemperance.)

‘Some precautions, it may be; but temperance, sir, is one thing, and abstinence another.’

‘But I have heard that, with some persons, temperance – that is moderation – is almost impossible; and if abstinence be an evil (which some have doubted), no one will deny that excess is a greater. Some parents have entirely prohibited their children from tasting intoxicating liquors; but a parent’s authority cannot last for ever: children are naturally prone to hanker after forbidden things; and a child, in such a case, would be likely to have a strong curiosity to taste, and try the effect of what has been so lauded and enjoyed by others, so strictly forbidden to himself – which curiosity would generally be gratified on the first convenient opportunity; and the restraint once broken, serious consequences might ensue. I don’t pretend to be a judge of such matters, but it seems to me, that this plan of Mrs Graham’s, as you describe it, Mrs Markham, extraordinary as it may be, is not without its advantages; for here you see, the child is delivered at once from temptation; he has no secret curiosity, no hankering desire; he is as well acquainted with the tempting liquors as he ever wishes to be; and is thoroughly disgusted with them without having suffered from their effects.’

‘And is that right, sir? Have I not proven to you how wrong it is – how contrary to Scripture and to reason to teach a child to look with contempt and disgust upon the blessings of Providence, instead of to use them aright?’

‘You may consider laudanum a blessing of Providence, sir,’ replied Mr Lawrence, smiling; ‘and yet, you will allow that most of us had better abstain from it, even in moderation; but,’ added he, ‘I would not desire you to follow out my simile too closely – in witness whereof I finish my glass.’

‘And take another I hope, Mr Lawrence,’ said my mother, pushing the bottle towards him.

He politely declined, and pushing his chair a little away from the table, leant back towards me – I was seated a trifle behind, on the sofa beside Eliza Millward – and carelessly asked me if I knew Mrs Graham.

‘I have met her once or twice,’ I replied.

‘What do you think of her?’

‘I cannot say that I like her much. She is handsome – or rather I should say distinguished and interesting – in her appearance, but by no means amiable – a woman liable to take strong prejudices, I should fancy, and stick to them through thick and thin, twisting everything into conformity with her own preconceived opinions – too hard, too sharp, too bitter for my taste.’

He made no reply, but looked down and bit his lip and shortly after rose and sauntered up to Miss Wilson, as much repelled by me, I fancy, as attracted by her. I scarcely noticed it at the time, but afterwards, I was led to recall this and other trifling facts, of a similar nature, to my remembrance, when – but I must not anticipate.

We wound up the evening with dancing – our worthy pastor thinking it no scandal to be present on the occasion, though one of the village musicians was engaged to direct our evolutions with his violin. But Mary Millward obstinately refused to join us; and so did Richard Wilson, though my mother earnestly entreated him to do so, and even offered to be his partner.

We managed very well without them, however. With a single set of quadrilles, and several country dances, we carried it on to a pretty late hour; and at length, having called upon our musician to strike up a waltz, I was just about to whirl Eliza round in that delightful dance, accompanied by Lawrence and Jane Wilson, and Fergus and Rose, when Mr Millward interposed with, –

‘No, no, I don’t allow that! Come, it’s time to be going now.’

‘Oh, no, papa!’ pleaded Eliza.

‘High time my girl – high time! – Moderation in all things remember! That’s the plan – “Let your moderation be known unto all men!”’

But in revenge, I followed Eliza into the dimly lighted passage, where under pretence of helping her on with her shawl, I fear I must plead guilty to snatching a kiss behind her father’s back, while he was enveloping his throat and chin in the folds of a mighty comforter. But alas! in turning round, there was my mother close beside me. The consequence was, that no sooner were the guests departed, than I was doomed to a very serious remonstrance, which unpleasantly checked the galloping course of my spirits, and made a disagreeable close to the evening.

‘My dear Gilbert,’ said she, ‘I wish you wouldn’t do so! You know how deeply I have your advantage at heart, how I love you and prize you above everything else in the world, and how much I long to see you well settled in life – and how bitterly it would grieve me to see you married to that girl – or any other in the neighbourhood. What you see in her I don’t know. It isn’t only the want of money that I think about – nothing of the kind – but there’s neither beauty, nor cleverness, nor goodness, nor anything else that’s desirable. If you knew your own value as I do, you wouldn’t dream of it. Do wait awhile and see! If you bind yourself to her, you’ll repent it all your life-time when you look round you and see how many better there are. Take my word for it, you will.’

‘Well mother, do be quiet! – I hate to be lectured! – I’m not going to marry yet, I tell you; but – dear me! mayn’t I enjoy myself at all?’

‘Yes, my dear boy, but not in that way. Indeed you shouldn’t do such things. You would be wronging the girl, if she were what she ought to be; but I assure you she is as artful a little hussy as anybody need wish to see; and you’ll get entangled in her snares before you know where you are. And if you do marry her Gilbert, you’ll break my heart – so there’s an end of it.’

‘Well, don’t cry about it mother,’ said I; for the tears were gushing from her eyes, ‘there, let that kiss efface the one I gave Eliza; don’t abuse her any more, and set your mind at rest; for I’ll promise never to – that is, I’ll promise to – to think twice before I take any important step you seriously disapprove of.’

So saying, I lighted my candle, and went to bed, considerably quenched in spirit.

CHAPTER 5 The Studio

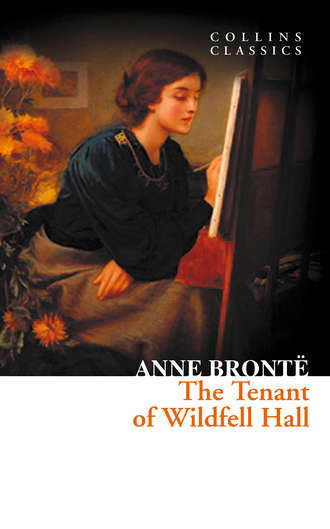

It was about the close of the month, that, yielding at length to the urgent importunities of Rose, I accompanied her in a visit to Wildfell Hall. To our surprise, we were ushered into a room where the first object that met the eye was a painter’s easel, with a table beside it covered with rolls of canvas, bottles of oil and varnish, palette, brushes, paints, etc. Leaning against the wall were several sketches in various stages of progression, and a few finished paintings – mostly of landscapes and figures.

‘I must make you welcome to my studio,’ said Mrs Graham; ‘there is no fire in the sitting room today, and it is rather too cold to show you into a place with an empty grate.’

And disengaging a couple of chairs from the artistical lumber that usurped them, she bid us be seated, and resumed her place beside the easel – not facing it exactly, but now and then glancing at the picture upon it while she conversed, and giving it an occasional touch with her brush, as if she found it impossible to wean her attention entirely from her occupation to fix it upon her guests. It was a view of Wildfell Hall, as seen at early morning from the field below, rising in dark relief against a sky of clear silvery blue, with a few red streaks on the horizon, faithfully drawn and coloured, and very elegantly and artistically handled.

‘I see your heart is in your work, Mrs Graham,’ observed I: ‘I must beg you to go on with it; for if you suffer our presence to interrupt you, we shall be constrained to regard ourselves as unwelcome intruders.’

‘Oh, no!’ replied she, throwing her brush on to the table, as if startled into politeness. ‘I am not so beset with visitors, but that I can readily spare a few minutes to the few that do favour me with their company.’

‘You have almost completed your painting,’ said I, approaching to observe it more closely, and surveying it with a greater degree of admiration and delight than I cared to express. ‘A few more touches in the foreground will finish it I should think. – But why have you called it Fernley Manor, Cumberland, instead of Wildfell Hall,—shire?’ I asked, alluding to the name she had traced in small characters at the bottom of the canvas.

But immediately I was sensible of having committed an act of impertinence in so doing; for she coloured and hesitated; but after a moment’s pause, with a kind of desperate frankness, she replied, –

‘Because I have friends – acquaintances at least – in the world, from whom I desire my present abode to be concealed; and as they might see the picture, and might possibly recognize the style in spite of the false initials I have put in the corner, I take the precaution to give a false name to the place also, in order to put them on a wrong scent, if they should attempt to trace me out by it.’

‘Then you don’t intend to keep the picture?’ said I, anxious to say anything to change the subject.

‘No; I cannot afford to paint for my own amusement.’

‘Mamma sends all her pictures to London,’ said Arthur; ‘and somebody sells them for her there, and sends us the money.’

In looking round upon the other pieces, I remarked a pretty sketch of Lindenhope from the top of the hill; another view of the old hall, basking in the sunny haze of a quiet summer afternoon; and a simple but striking little picture of a child brooding with looks of silent, but deep and sorrowful regret, over a handful of withered flowers, with glimpses of dark low hills and autumnal fields behind it, and a dull beclouded sky above.

‘You see there is a sad dearth of subjects,’ observed the fair artist. ‘I took the old hall once on a moonlight night, and I suppose I must take it again on a snowy winter’s day, and then again on a dark cloudy evening; for I really have nothing else to paint. I have been told that you have a fine view of the sea somewhere in the neighbourhood – is it true? – and is it within walking distance?’

‘Yes, if you don’t object to walking four miles, – or nearly so – little short of eight miles there and back – and over a somewhat rough, fatiguing road.’

‘In what direction does it lie?’

I described the situation as well as I could, and was entering upon an explanation of the various roads, lanes, and fields to be traversed in order to reach it, the goings straight on, and turnings to the right, and the left, when she checked me with, –

‘Oh, stop! – don’t tell me now: I shall forget every word of your directions before I require them. I shall not think about going till next spring; and then, perhaps, I may trouble you. At present we have the winter before us, and –’

She suddenly paused, with a suppressed exclamation started up from her seat, and saying, ‘Excuse me one moment,’ hurried from the room, and shut the door behind her.

Curious to see what had startled her so, I looked towards the window, – for her eyes had been carelessly fixed upon it the moment before – and just beheld the skirts of a man’s coat vanishing behind a large holly bush that stood between the window and the porch.

‘It’s mamma’s friend,’ said Arthur.

Rose and I looked at each other.

‘I don’t know what to make of her, at all,’ whispered Rose.

The child looked at her in grave surprise. She straightway began to talk to him on indifferent matters, while I amused myself with looking at the pictures. There was one in an obscure corner that I had not before observed. It was a little child, seated on the grass with its lap full of flowers. The tiny features and large, blue eyes, smiling through a shock of light brown curls, shaken over the forehead as it bent above its treasure, bore sufficient resemblance to those of the young gentleman before me, to proclaim it a portrait of Arthur Graham in his early infancy.

In taking this up to bring it to the light, I discovered another behind it, with its face to the wall. I ventured to take that up too. It was the portrait of a gentleman in the full prime of youthful manhood – handsome enough, and not badly executed: but, if done by the same hand as the others, it was evidently some years before; for there was far more careful minuteness of detail, and less of that freshness of colouring and freedom of handling, that delighted and surprised me in them. Nevertheless, I surveyed it with considerable interest. There was a certain individuality in the features and expression that stamped it, at once, a successful likeness. The bright, blue eyes regarded the spectator with a kind of lurking drollery – you almost expected to see them wink; the lips – a little too voluptuously full – seemed ready to break into a smile; the warmly tinted cheeks were embellished with a luxuriant growth of reddish whiskers; while the bright chestnut hair, clustering in abundant, wavy curls, trespassed too much upon the forehead, and seemed to intimate that the owner thereof was prouder of his beauty than his intellect – as perhaps, he had reason to be; – and yet he looked no fool.

I had not had the portrait in my hands two minutes before the fair artist returned.

‘Only someone come about the pictures,’ said she, in apology for her abrupt departure: ‘I told him to wait.’

‘I fear it will be considered an act of impertinence,’ said I, ‘to presume to look at a picture that the artist has turned to the wall; but may I ask’ –

‘It is an act of very great impertinence, sir; and therefore, I beg you will ask nothing about it, for your curiosity will not be gratified,’ replied she, attempting to cover the tartness of her rebuke with a smile; – but I could see, by her flushed cheek and kindling eye, that she was seriously annoyed.

‘I was only going to ask if you had painted it yourself,’ said I, sulkily resigning the picture into her hands; for without a grain of ceremony, she took it from me; and quickly restoring it to the dark corner, with its face to the wall, placed the other against it as before, and then turned to me and laughed.

But I was in no humour for jesting. I carelessly turned to the window, and stood looking out upon the desolate garden, leaving her to talk to Rose for a minute or two; and then, telling my sister it was time to go, shook hands with the little gentleman, coolly bowed to the lady, and moved towards the door. But, having bid adieu to Rose, Mrs Graham presented her hand to me, saying, with a soft voice, and by no means a disagreeable smile, –

‘Let not the sun go down upon your wrath, Mr Markham. I’m sorry I offended you by my abruptness.’

When a lady condescends to apologize, there is no keeping one’s anger of course; so we parted good friends for once; and this time, I squeezed her hand with a cordial, not a spiteful pressure.

CHAPTER 6 Progression

During the next four months, I did not enter Mrs Graham’s house, nor she mine; but still, the ladies continued to talk about her, and still, our acquaintance continued, though slowly, to advance. As for their talk, I paid but little attention to that (when it related to the fair hermit, I mean), and the only information I derived from it, was that, one fine, frosty day, she had ventured to take her little boy as far as the vicarage, and that, unfortunately, nobody was at home but Miss Millward; nevertheless, she had sat a long time, and, by all accounts, they had found a good deal to say to each other, and parted with a mutual desire to meet again. – But Mary liked children, and fond mammas like those who can duly appreciate their treasures.

But sometimes, I saw her myself, – not only when she came to church, but when she was out on the hills with her son, whether taking a long, purpose-like walk, or – on special fine days – leisurely rambling over the moor or the bleak pasture-lands surrounding the old hall, herself with a book in her hand, her son gambolling about her; and, on any of these occasions, when I caught sight of her in my solitary walks or rides, or while following my agricultural pursuits, I generally contrived to meet or overtake her; for I rather liked to see Mrs Graham, and to talk to her, and I decidedly liked to talk to her little companion, whom, when once the ice of his shyness was fairly broken, I found to be a very amiable, intelligent, and entertaining little fellow; and we soon became excellent friends – how much to the gratification of his mamma, I cannot undertake to say. I suspected at first, that she was desirous of throwing cold water on this growing intimacy – to quench, as it were, the kindling flame of our friendship – but discovering, at length, in spite of her prejudice against me, that I was perfectly harmless, and even well-intentioned, and that, between myself and my dog, her son derived a great deal of pleasure from the acquaintance, that he would not otherwise have known, she ceased to object, and even welcomed my coming with a smile.

As for Arthur, he would shout his welcome from afar, and run to meet me fifty yards from his mother’s side. If I happened to be on horseback, he was sure to get a canter or a gallop; or, if there was one of the draught horses within an available distance, he was treated to a steady ride upon that, which served his turn almost as well; but his mother would always follow and trudge beside him – not so much, I believe, to ensure his safe conduct, as to see that I instilled no objectionable notions into his infant mind; for she was ever on the watch, and never would allow him to be taken out of her sight. What pleased her best of all was to see him romping and racing with Sancho, while I walked by her side – not, I fear, for love of my company (though I sometimes deluded myself with that idea), so much as for the delight she took in seeing her son thus happily engaged in the enjoyment of those active sports, so invigorating to his tender frame, yet so seldom exercised for want of playmates suited to his years; and, perhaps, her pleasure was sweetened, not a little, by the fact of my being with her instead of with him; and therefore incapable of doing him any injury directly or indirectly, designedly or otherwise – small thanks to her for that same.

But sometimes, I believe, she really had some little gratification in conversing with me; and one bright February morning, during twenty minutes’ stroll along the moor, she laid aside her usual asperity and reserve, and fairly entered into conversation with me, discoursing with so much eloquence, and depth of thought and feeling, on a subject, happily coinciding with my own ideas, and looking so beautiful withal, that I went home enchanted; and on the way (morally) started to find myself thinking that, after all, it would, perhaps, be better to spend one’s days with such a woman than with Eliza Millward; – and then I (figuratively) blushed for my inconstancy.

On entering the parlour, I found Eliza there, with Rose and no one else. The surprise was not altogether so agreeable as it ought to have been. We chatted together a long time; but I found her rather frivolous, and even a little insipid, compared with the more mature and earnest Mrs Graham – Alas, for human constancy!

‘However,’ thought I, ‘I ought not to marry Eliza since my mother so strongly objects to it, and I ought not to delude the girl with the idea that I intended to do so. Now, if this mood continue, I shall have less difficulty in emancipating my affections from her soft, yet unrelenting sway; and, though Mrs Graham might be equally objectionable, I may be permitted, like the doctors, to cure a greater evil by a less; for I shall not fall seriously in love with the young widow, I think, – nor she with me – that’s certain – but if I find a little pleasure in her society, I may surely be allowed to seek it; and if the star of her divinity be bright enough to dim the lustre of Eliza’s, so much the better; but I scarcely can think it.’

And thereafter, I seldom suffered a fine day to pass without paying a visit to Wildfell, about the time my new acquaintance usually left her hermitage; but so frequently was I balked in my expectations of another interview, so changeable was she in her times of coming forth, and in her places of resort, so transient were the occasional glimpses I was able to obtain, that I felt half inclined to think she took as much pains to avoid my company, as I to seek hers; but this was too disagreeable a supposition to be entertained a moment after it could, conveniently, be dismissed.

One calm, clear afternoon, however, in March, as I was superintending the rolling of the meadow-land, and the repairing of a hedge in the valley, I saw Mrs Graham down by the brook, with a sketch-book in her hand, absorbed in the exercise of her favourite art, while Arthur was putting on the time with constructing dams and breakwaters in the shallow, stony stream. I was rather in want of amusement, and so rare an opportunity was not to be neglected; so, leaving both meadow and hedge, I quickly repaired to the spot, – but not before Sancho, who, immediately upon perceiving his young friend, scoured at full gallop the intervening space, and pounced upon him with an impetuous mirth that precipitated the child almost into the middle of the beck; but, happily, the stones preserved him from any serious wetting, while their smoothness prevented his being too much hurt to laugh at the untoward event.