Полная версия

The Taming of the Shrew

In fact, we only know of Shakespeare’s work because two of his friends had the foresight to collect his plays together following his death and have them printed. The only reason they did so was apparently because they rated his talent and thought it would be a shame if his words were lost.

Consequently his body of work has ever since been assessed and reassessed as the greatest contribution to English literature. That is despite the fact that we know that different printers took it upon themselves to heavily edit the material they worked from. We also know that Elizabethan plays were worked and reworked frequently, so that they evolved over time until they were honed to perfection, which means that many different hands played their part in the active writing process. It would therefore be fair to say that any play attributed to Shakespeare is unlikely to contain a great deal of original input. Even the plots were based on well known historical events, so it would be hard to know what fragments of any Shakespeare play came from that single mind.

One might draw a comparison with the Christian bible, which remains such a compelling read because it came from the collaboration of many contributors and translators over centuries, who each adjusted the stories until they could no longer be improved. As virtually nothing is known of Shakespeare’s life and even less about his method of working, we shall never know the truth about his plays. They certainly contain some very elegant phrasing, clever plot devices and plenty of words never before seen in print, but as to whether Shakespeare invented them from a unique imagination or whether he simply took them from others around him is anyone’s guess.

The best bet seems to be that Shakespeare probably took the lead role in devising the original drafts of the plays, but was open to collaboration from any source when it came to developing them into workable scripts for effective performances. He would have had to work closely with his fellow actors in rehearsals, thereby finding out where to edit, abridge, alter, reword and so on.

In turn, similar adjustments would have occurred in his absence, so that definitive versions of his plays never really existed. In effect Shakespeare was only responsible for providing the framework of plays, upon which others took liberties over time. This wasn’t helped by the fact that the English language itself was not definitive at that time either. The consequence was that people took it upon themselves to spell words however they pleased or to completely change words and phrasing to suit their own preferences.

It is easy to see then, that Shakespeare’s plays were always going to have lives of their own, mutating and distorting in detail like Chinese whispers. The culture of creative preservation was simply not established in Elizabethan England. Creative ownership of Shakespeare’s plays was lost to him as soon as he released them into the consciousness of others. They saw nothing wrong with taking his ideas and running with them, because no one had ever suggested that one shouldn’t, and Shakespeare probably regarded his work in the same way. His plays weren’t sacrosanct works of art, they were templates for theatre folk to make their livings from, so they had every right to mould them into productions that drew in the crowds as effectively as possible. Shakespeare was like the helmsman of a sailing ship, steering the vessel but wholly reliant on the team work of his crew to arrive at the desired destination.

It seems that Shakespeare certainly had a natural gift, but the genius of his plays may be attributable to the collective efforts of Shakespeare and others. It is a rather satisfying notion to think that his plays might actually be the creative outpourings of the Elizabethan milieu in which Shakespeare immersed himself. That makes them important social documents as well as seminal works of the English language.

Money in Shakespeare’s Day

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to relate the value of money in our time to its value in another age and to compare prices of commodities today and in the past. Many items are simply not comparable on grounds of quality or serviceability.

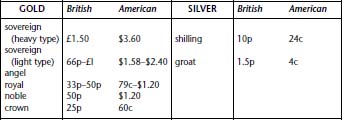

There was a bewildering variety of coins in use in Elizabethan England. As nearly all English and European coins were gold or silver, they had intrinsic value apart from their official value. This meant that foreign coins circulated freely in England and were officially recognized, for example the French crown (écu) worth about 30p (72 cents), and the Spanish ducat worth about 33p (79 cents). The following table shows some of the coins mentioned by Shakespeare and their relation to one another.

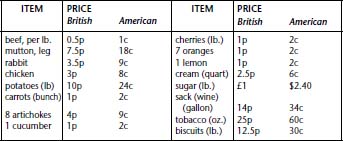

A comparison of the following prices in Shakespeare’s time with the prices of the same items today will give some idea of the change in the value of money.

INTRODUCTION

Michael Bogdanov’s modern-dress production of The Taming of the Shrew in 1979 was well received in terms of its theatrical competence but a number of critics felt that however well done, it had better not been done at all. Michael Billington in the Guardian doubted that there was any reason to revive a play ‘that seems totally offensive to our age and our society. My own feeling is that it should be put back firmly and squarely on the shelf’. Suggestions of censorship, as it were, have at least the merit of indicating that the offending object is being taken seriously, nor is Billington the first to find The Shrew a peculiarly damning blot on Shakespeare’s output: Shaw famously registered shame at ‘the lord-of-creation moral implied in the wager and the speech put into the woman’s own mouth’. The Shrew has generally proved a bit of a facer for those who would claim that Shakespeare is a great universal genius with ideas that transcend the limitations of his time. Hence the tendency of modern readings and productions either to imply that Shakespeare did not really acquiesce in the apparent patriarchal assumptions of the taming plot (nor the reductiveness about female charm implied in Bianca’s defection from maidenly modesty), or to suggest that even if he did, the usefulness of the play for the twentieth century is to expose the latent misogyny and brutality that still form the real infrastructure of our bien pensant, politically correct culture.

One way of distancing Shakespeare from the implications of the taming plot has been to repair the broken frame of the play, increasing the significance of the Sly plot by importing material from the anonymous The Taming of a Shrew, printed in 1594 and possibly a ‘memorial reconstruction’ of a Shakespearean original. The taming and submission of Katherine can then be made to appear an unattainable and possibly rather vulgar male fantasy of domination, a dream of empowerment not unlike the violent fantasies of Pirate Jenny in Brecht’s Threepenny Opera. Alternatively, the play can be made to appear more coherent by privileging one or other of its generic modes. On the one hand by ignoring the incipient psychological complexity in the treatment of Katherine in particular (she is after all not the favoured child of her father and Bianca’s butter-wouldn’t-melt-in-her-mouth demeanour might irritate more than a shrew), and taking the whole as a farcical romp with no power to move or upset. On the other side, the farcical nastinesses can be played down in favour of modern notions of relationship where all is fair between the couple because they really love each other, win through to equality within properly constituted hierarchy, and are even, in the most sentimental versions of such a reading, complicit in Kate’s response to the wager.

Certainly H. J. Oliver in his introduction to the New Oxford edition of the play feels that Shakespeare’s not having provided a generically consistent play is a consequence of his youthfulness when he devised it – it is ‘a young dramatist’s attempt to mingle two genres that cannot be combined’. But if generic miscegenation is an effect of youth, then it is surprising to find it again in All’s Well That Ends Well and Measure for Measure. Since in these plays it does much to earn the description ‘problem plays’, it might be well to consider if this is not also the effect in The Shrew. The clash of farcical folk-tale in the taming plot with the legitimate desires of both Petruchio and Katherine for lives that they can live, betrays the inconsistences and half-truths that are daily tolerated and evaded. There seems to me no possible way of doubting that Shakespeare presents Katherine’s speech of submission to an idealised hierarchy of gender relationships without irony, but he surely does not do so without thought or without demonstrating the worst that can be said about its potential for physical and psychological tyranny.

The rewards for Katherine’s submission in life, as it were, are presumably those ‘good days and long’ that Petruchio has already stated as his goal. Since it comes as a definitive culmination to the action, the audience is left with no sense of need for its endless repetition, it frames a way of life, while shrewishness is on the contrary a lifetime career, the future of Bianca and the widow. This is not modern but it is not too bad in the circumstances. And the reward in the theatre is the complete stage dominance of Kate. It is possible, of course, to pluck weary disaster out of Katherine’s eloquent dignity but it seems not worth the trouble.

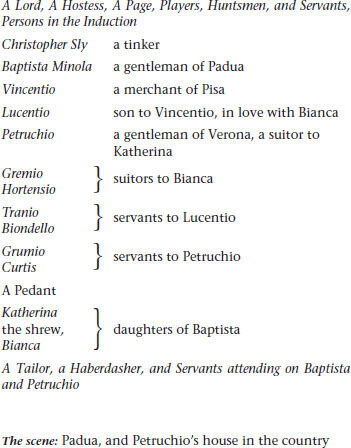

LIST OF CHARACTERS

INDUCTION

Scene I

Before an alehouse on a heath.

[Enter Hostess and SLY.]

Sly

I’ll pheeze you, in faith.

Hostess

A pair of stocks, you rogue!

Sly

Y’are a baggage; the Slys are no rogues. Look in the chronicles: we came in with Richard Conqueror. Therefore, paucas pallabris; let the world slide. Sessa! 5Hostess

You will not pay for the glasses you have burst?

Sly

No, not a denier. Go by, Saint Jeronimy, go to thy cold bed and warm thee.

Hostess

I know my remedy; I must go fetch the thirdborough.

[Exit.]

Sly

Third, or fourth, or fifth borough, I’ll answer him by law. I’ll not budge an inch, boy; let him come, and kindly. [Falls asleep.] 10[Wind horns. Enter a Lord from hunting, with his Train.]

Lord

Huntsman, I charge thee, tender well my hounds;

Brach Merriman, the poor cur, is emboss’d;

And couple Clowder with the deep-mouth’d brach. 15Saw’st thou not, boy, how Silver made it good

At the hedge corner, in the coldest fault?

I would not lose the dog for twenty pound.

1 Huntsman

Why, Belman is as good as he, my lord;

He cried upon it at the merest loss, 20And twice to-day pick’d out the dullest scent;

Trust me, I take him for the better dog.

Lord

Thou art a fool; if Echo were as fleet,

I would esteem him worth a dozen such.

But sup them well, and look unto them all; 25To-morrow I intend to hunt again.

1 Huntsman

I will, my lord.

Lord

What’s here? One dead, or drunk?

See, doth he breathe?

2 Huntsman

He breathes, my lord. Were he not warm’d with ale, 30This were a bed but cold to sleep so soundly.

Lord

O monstrous beast, how like a swine he lies!

Grim death, how foul and loathsome is thine image!

Sirs, I will practise on this drunken man.

What think you, if he were convey’d to bed, 35Wrapp’d in sweet clothes, rings put upon his fingers,

A most delicious banquet by his bed,

And brave attendants near him when he wakes,

Would not the beggar then forget himself?

1 Huntsman

Believe me, lord, I think he cannot choose. 402 Huntsman

It would seem strange unto him when he wak’d.

Lord

Even as a flatt’ring dream or worthless fancy.

Then take him up, and manage well the jest:

Carry him gently to my fairest chamber,

And hang it round with all my wanton pictures; 45Balm his foul head in warm distilled waters,

And burn sweet wood to make the lodging sweet;

Procure me music ready when he wakes,

To make a dulcet and a heavenly sound;

And if he chance to speak, be ready straight, 50And with a low submissive reverence

Say ‘What is it your honour will command?’

Let one attend him with a silver basin

Full of rose-water and bestrew’d with flowers;

Another bear the ewer, the third a diaper, 55And say ‘Will’t please your lordship cool your hands?’

Some one be ready with a costly suit,

And ask him what apparel he will wear;

Another tell him of his hounds and horse,

And that his lady mourns at his disease; 60Persuade him that he hath been lunatic,

And, when he says he is, say that he dreams,

For he is nothing but a mighty lord.

This do, and do it kindly, gentle sirs;

It will be pastime passing excellent, 65If it be husbanded with modesty.

1 Huntsman

My lord, I warrant you we will play our part

As he shall think by our true diligence

He is no less than what we say he is.

Lord

Take him up gently, and to bed with him; 70And each one to his office when he wakes.

[SLY is carried out. A trumpet sounds.]

Sirrah, go see what trumpet ’tis that sounds –

[Exit Servant.]

Belike some noble gentleman that means,

Travelling some journey, to repose him here.

[Re-enter a Servant.]

How now! who is it?

Servant

An’t please your honour, players 75That offer service to your lordship.

Lord

Bid them come near.

[Enter Players.]

Now, fellows, you are welcome.

Players

We thank your honour.

Lord

Do you intend to stay with me to-night?

Player

So please your lordship to accept our duty. 80Lord

With all my heart. This fellow I remember

Since once he play’d a farmer’s eldest son;

’Twas where you woo’d the gentlewoman so well.

I have forgot your name; but, sure, that part

Was aptly fitted and naturally perform’d. 85Player

I think ’twas Soto that your honour means.

Lord

’Tis very true; thou didst it excellent.

Well, you are come to me in a happy time,

The rather for I have some sport in hand

Wherein your cunning can assist me much. 90There is a lord will hear you play to-night;

But I am doubtful of your modesties,

Lest, over-eying of his odd behaviour,

For yet his honour never heard a play,

You break into some merry passion 95And so offend him; for I tell you, sirs,

If you should smile, he grows impatient.

Player

Fear not, my lord; we can contain ourselves,

Were he the veriest antic in the world.

Lord

Go, sirrah, take them to the buttery, 100And give them friendly welcome every one;

Let them want nothing that my house affords.

[Exit one with the Players.]

Sirrah, go you to Barthol’mew my page,

And see him dress’d in all suits like a lady;

That done, conduct him to the drunkard’s chamber, 105And call him ‘madam’, do him obeisance.

Tell him from me – as he will win my love –

He bear himself with honourable action,

Such as he hath observ’d in noble ladies

Unto their lords, by them accomplished; 110Such duty to the drunkard let him do,

With soft low tongue and lowly courtesy,

And say ‘What is’t your honour will command,

Wherein your lady and your humble wife

May show her duty and make known her love?’ 115And then with kind embracements, tempting kisses,

And with declining head into his bosom,

Bid him shed tears, as being overjoyed

To see her noble lord restor’d to health,

Who for this seven years hath esteemed him 120No better than a poor and loathsome beggar.

And if the boy have not a woman’s gift

To rain a shower of commanded tears,

An onion will do well for such a shift,

Which, in a napkin being close convey’d 125Shall in despite enforce a watery eye.

See this dispatch’d with all the haste thou canst;

Anon I’ll give thee more instructions.

[Exit a Servant.]

I know the boy will well usurp the grace,

Voice, gait, and action, of a gentlewoman; 130I long to hear him call the drunkard ‘husband’;

And how my men will stay themselves from laughter

When they do homage to this simple peasant.

I’ll in to counsel them; haply my presence

May well abate the over-merry spleen, 135Which otherwise would grow into extremes.

[Exeunt.]

Scene II

A bedchamber in the Lord’s house.

[Enter aloft SLY, with Attendants; some with apparel, basin and ewer, and other appurtenances; and Lord.]

Sly

For God’s sake, a pot of small ale.

1 Servant

Will’t please your lordship drink a cup of sack?

2 Servant

Will’t please your honour taste of these conserves?

3 Servant

What raiment will your honour wear to-day?

Sly

I am Christophero Sly; call not me ‘honour’ nor ‘lordship’. I ne’er drank sack in my life; and if you give me any conserves, give me conserves of beef. Ne’er ask me what raiment I’ll wear, for I have no more doublets than backs, no more stockings than legs, nor no more shoes than feet – nay, sometime more feet than shoes, or such shoes as my toes look through the overleather. 510Lord

Heaven cease this idle humour in your honour!

O, that a mighty man of such descent,

Of such possessions, and so high esteem,

Should be infused with so foul a spirit! 15Sly

What, would you make me mad? Am not I Christopher Sly, old Sly’s son of Burton Heath; by birth a pedlar, by education a cardmaker, by transmutation a bearherd, and now by present profession a tinker? Ask Marian Hacket, the fat alewife of Wincot, if she know me not; if she say I am not fourteen pence on the score for sheer ale, score me up for the lying’st knave in Christendom. What! I am not bestraught. 20[Taking a pot of ale]

Here’s –

3 Servant

O, this it is that makes your lady mourn! 252 Servant

O, this is it that makes your servants droop!

Lord

Hence comes it that your kindred shuns your house,

As beaten hence by your strange lunacy.

O noble lord, bethink thee of thy birth!

Call home thy ancient thoughts from banishment, 30And banish hence these abject lowly dreams.

Look how thy servants do attend on thee,

Each in his office ready at thy beck.

Wilt thou have music? Hark! Apollo plays,

[Music.]

And twenty caged nightingales do sing. 35Or wilt thou sleep? We’ll have thee to a couch

Softer and sweeter than the lustful bed

On purpose trimm’d up for Semiramis.

Say thou wilt walk: we will bestrew the ground.

Or wilt thou ride? Thy horses shall be trapp’d, 40Their harness studded all with gold and pearl.

Dost thou love hawking? Thou hast hawks will soar

Above the morning lark. Or wilt thou hunt?

Thy hounds shall make the welkin answer them

And fetch shrill echoes from the hollow earth. 451 Servant

Say thou wilt course; thy grey-hounds are as swift

As breathed stags; ay, fleeter than the roe.

2 Servant

Dost thou love pictures? We will fetch thee straight

Adonis painted by a running brook,

And Cytherea all in sedges hid, 50Which seem to move and wanton with her breath

Even as the waving sedges play wi’ th’ wind.

Lord