Полная версия

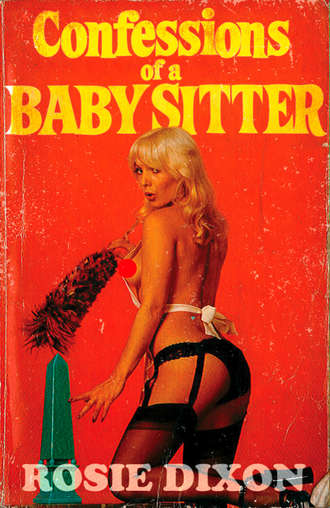

Confessions of a Babysitter

‘You heard what your father said, dear,’ says Mum. ‘It’s not very nice.’

‘It’s unhygienic,’ I say. ‘I don’t want them after her filthy hands have been grubbing through them.’

‘My hands aren’t filthy,’ says Natalie provocatively. ‘I wash them as often as you do,’

‘That’s true,’ I say. ‘I can tell by the marks on the towels. When are you going to learn to use your own?’

‘I didn’t think you had a towel,’ says Natalie. ‘You’re here so seldom, I don’t see the point.’

‘You use the place like a hotel,’ says Dad. I might have guessed he would team up with Natalie. She has always been his favourite. I take a mouthful of Sugar Puffs and try to look hurt. It is not easy because I spill some of them and can feel one of them sticking to the corner of my mouth.

‘Don’t be unkind to the girl, Harry,’ says Mum. ‘She only came home last night.’

‘I suppose we should be thankful for that,’ says Dad. ‘It’s usually first thing in the morning.’

Natalie sniggers and I could kill her. She has such a vulgar laugh. ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’ I say angrily.

‘You know what I mean,’ says Dad. ‘Don’t play the innocent with me, my girl. It won’t wash.’

‘Now, now,’ says Mum. ‘Let’s have no unpleasantness. I’m very happy that Rose is home again. I don’t know why she always wants to leave us.’ She sniffs and dabs her eye with her apron.

‘I don’t want to leave you, Mum,’ I say. ‘It’s everybody getting at me that I can’t stand.’

‘Nobody’s getting at you,’ says Dad. ‘I’m just commenting on a matter of fact, that’s all. You’ve always kept unreliable hours. It’s a symptom of your whole way of going on. Look at the jobs you’ve had. Not just jobs – professions most of them. Nursing, teaching. You couldn’t make a go of any of them. Then that escort business.’

‘I was never in favour of that,’ says Mum. ‘I think that’s where she made her mistake. She should have stuck at the teaching. They need teachers.’

‘I don’t think she had a chance to stick,’ says Dad, coming over all malevolent. ‘Redundant is a word you hear a lot of these days but never more so than from our little Rose. I think she gets the push for reasons that have nothing to do with the plight of this once great country of ours – well, not directly anyway.’

‘I don’t know what you mean, Dad,’ I say.

‘Oh yes you do!’ says Natalie. ‘I remember when we had that coach party here. I saw what was going on in the bathroom.’

‘You nosy little slut!’ I say – what was going on in the bathroom was unpleasant as readers of Confessions of a Lady Courier will recall, but it is even worse if you have your kid sister revealing the lowdown on the distressing details. A sensitive nature can stand so much.

‘Watch your language, young lady!’ snaps Dad. ‘You may think you’re grown up, but you don’t have leave to talk like that.’

‘Don’t start snivelling!’ I say to Natalie, who is encouraging her lip to tremble. ‘You’re not really upset – and stop borrowing my bras!’ I catch a glimpse of a familiar strap as the little brat leans forward. It has Geoffrey Wilkes’s teeth marks on it. Down at the Eastwood tennis club they think of him as an old square but he can get quite frisky if someone overdoes the beer in his lemonade shandy.

‘What would I want to borrow your rotten old bras for?’ says my odious little sister. ‘They’re too small anyway.’

I nearly slap her when she says that. She is well-developed for her age – possibly too well-developed – but everybody agrees that my upper body is one of my best features.

‘Mum!’ I exclaim. ‘How can you let her talk like that?’

‘You raised the subject,’ says Dad.

‘Now, now, both of you,’ says Mum, twisting the tea towel into knots. ‘Let’s have no more of that. Rosie’s back in the bosom of the family – ’ she breaks off and smiles nervously. ‘You know what I mean?’

‘Yes, Mary,’ says Dad irritably. ‘Well, I must be on my way. Time and tide wait for no man. We can’t get Britain back on her feet if we spend all day loafing round the breakfast table.’ He looks at me pointedly when he says that. ‘Perhaps I may be permitted to ask what form of employment you are next thinking of indulging in?’

When he does his Mr Sarky-boots bit I feel like emptying the Sugar Puffs all over him. ‘I’d like to do something with kids,’ I say.

Even Mum looks surprised and Dad stares at me like I have suggested a career as a child molester. ‘Looking after them?’ he says.

‘That’s right,’ I say.

‘Good heavens,’ says Dad. ‘You can’t look after yourself. Who’s going to employ you as a nursemaid?’

‘I happen to have had a very good offer already,’ I say loftily. ‘With an Italian family on the Po.’

‘Blimey, they must need some help,’ says Dad.

I raise my eyes to the ceiling and try to indicate how he lowers himself when he makes jokes like that.

‘The Po is an Italian river, Dad,’ I say patiently.

‘Oh yes?’ Dad’s new-found perkiness tells me that another terrible funny is on the way. ‘I always thought the Po was in China!’

Creeper Natalie laughs heartily and I seek Mum’s eyes for a sympathetic exchange of glances. ‘All this reminds me, Natalie,’ she says. ‘You haven’t forgotten that you’re babysitting for the Wilkinsons tonight?’

Natalie’s face clouds over. ‘Do I have to, Mum? It’s Folk Night at the youth club.’

‘It’s what?’ Dad sounds worried.

‘Folk Night,’ says Natalie.

‘You should have thought when I asked you,’ says Mum. ‘It’s Mrs Wilkinson’s amateur dramatics tonight. She’s appearing in Howard’s End.’

‘I’m surprised it isn’t vice versa, knowing her,’ says Dad. ‘They’re very free and easy, those Wilkinsons.’

‘You can’t back out now,’ says Mum. ‘She asked me specially. It’s the first night, and her husband wants to be there.’

‘Oh, Mum,’ whines Natalie. ‘Do I have to?’

‘Why don’t I go?’ I say. ‘I’ve got nothing else to do. The Wilkinsons have got a couple of little boys, haven’t they?’

‘That’s right, dear,’ says Mum. ‘Courtenay and Benedict. Are you sure you don’t mind?’

‘Thanks, Rosie,’ says Natalie grudgingly. ‘I charge a quid up to midnight and 50p for every hour or part of an hour after.’

Just like when I was working for an escort agency, I think to myself. And then – BANG! – the germ of an idea hits me. Maybe this is what I should be doing. A babysitting service. I know that Natalie is always being asked if she will oblige and if people are prepared to have her dropping cigarette ash all over their carpets and necking with her ghastly boyfriends – not to mention all the other terrible things I am certain they get up to – then I am certain that an efficient and wholesome babyminding service would be much in demand. I will use tonight as a trial run and then talk to Penny about the idea. We could probably recruit other girls and take a commission. After working for so many crummy organisations which have exploited me it seems a good idea to start one of my own. I don’t mean a crummy one, of course. The Dixon Night Guard Service will be above reproach and reflect all its founder’s principles and ideals. Maybe, one day, people will think of me in the same breath as Flora MacNightingale and Madame Puree.

The Wilkinsons live in a detached house a few streets from us. Mr Wilkinson works with Dad, though a few rungs higher up the management ladder and our families are not what you would call close. Whenever Mrs Wilkinson beams at me in the street I know that she is going to ask if Natalie can babysit. Otherwise, she just passes by as if she has not seen me. I ring the doorbell and listen to the chimes dying away into the far corners of the house. I can hear a child screaming which is not a good sign and when Mr Wilkinson opens the door he looks harassed. He is wearing dinner jacket trousers and is obviously having trouble tying his bow tie.

‘Ah,’ he says. ‘Good. It’s – er – – ’

‘Rose,’ I say. ‘I’ve come instead of Natalie. I hope that’s all right?’

Mr Wilkinson looks me up and down and strokes the front of his shirt absentmindedly. ‘Yes,’ he says. ‘Very definitely. Come in. My wife’s gone on because she has to be made up. She’s appearing in a play, you know.’

‘Howard’s End,’ I say. He is a good-looking man with a thin moustache and a lot of lines round his eyes. There is a little flesh under his chin but he is quite well preserved. I suppose he must be about forty.

‘That’s right. Come into the living room. Would you like a drink?’ He leads the way into a comfortable lounge with a lot of leather-backed chairs and nods towards a well-stocked bar that takes up one corner of it.

‘Well,’ I say. ‘I don’t want to hold you up.’

‘You won’t have to hold me up if I only have one drink,’ he says with a laugh. How refreshing to be in the company of a witty man after Dad. ‘A quick gin won’t do any harm.’ He pressed a switch and a pottery figurine of a drunk leaning against a lamp post lights up and says ‘Bar’s open’.

‘That’s clever,’ I say.

‘I’ll show you some of my other knick knacks when I know you better.’ Mr Wilkinson winks at me. ‘Ice and lemon?’

‘Er – yes,’ I say registering with some alarm that there seems to be quite a lot of gin in my glass. ‘Is it all right to let the child scream like that?’

Mr Wilkinson chinks his glass against mine. ‘Cheers! Oh yes. Exercises their lungs. Benedict always has a good bawl before he settles down.’ He listens for a moment. ‘Or maybe it’s Courtenay.’

‘Nice names,’ I say.

‘Mine’s Rex,’ he says. ‘You know, Sexy Rexy.’ He winks at me again and waggles the flapping ends of his bow tie. ‘Do you know how to tie one of these?’

‘It’s not like a bootlace, is it?’ I ask.

‘No, you have to bring the end back somehow. It’s a nuisance. I’ve got a clip-on one upstairs but it’s not velvet.’

‘Perhaps you could take that apart and see how they do it?’ I suggest.

Mr Wilkinson shakes his head admiringly. ‘You’re not just a pretty face, are you darling? Come upstairs and I’ll introduce you to the kids.’

I had formed an impression of Courtenay and Benedict as being two golden-haired little mites with their hair cut in fringes. The reality is somewhat different. A hulking twelve-year-old is emerging from the toilet as we hit the top of the stairs. ‘What has your mother told you, Benedict?’ says Mr Wilkinson wearily.

‘I haven’t done it on the floor!’ shouts the child like it has been unjustly accused of murder.

‘Pull the chain!’ bellows Mr Wilkinson.

‘I was just going to do it,’ says Benedict.

‘Don’t lie to me, boy!’

‘I was, Dad!’

‘You were walking away from the toilet, you bloody little liar! The lady saw you!’

‘Maybe he just remembered,’ I say, trying to pour oil on troubled waters.

Mr Wilkinson sticks his head inside the toilet. ‘What do you mean you didn’t do it on the floor!?’

‘That wasn’t me, that was Courtenay!’

The crying that has continued unabated from the moment I crossed the threshold ceases instantly. ‘Dad! Dad! He’s lying. I haven’t been to the toilet since I got home.’ An even less appealing version of Benedict appears at the top of the stairs. He is wearing pyjama trousers with the front gaping open.

‘You liar! Whose toy soldier is that down there, then?’

‘Dad! Dad! He put my toy soldier down the toilet!’

‘Liar! You were playing glacier skiing and he slipped.’

‘Ooooh! You rotten liar!’

There is a thunder of bare feet and two bodies lock in the middle of the stairs. ‘Go to your room, both of you!’ shouts Mr Wilkinson. ‘Your mother will have something to say about this.’

‘He’s a liar!’

‘Shut up!’

‘I hate you!’

‘Bully!’

Mr Wilkinson picks up the bundle of flailing arms and legs and throws it through the door at the top of the stairs. He closes the door firmly and dusts his hands together.

‘They won’t give you any trouble,’ he says, sounding as if he would like to believe it. ‘Just normal high-spirited kids.’ He rips open the door and I see the veins at his forehead bulge like burnished worm casts. ‘One more word and I’ll swing for you!’ In the silence that follows you could hear a nappy pin drop. Mr Wilkinson closes the door with a wry smile. ‘It’s just a question of knowing how to handle them,’ he says, flexing and unflexing his fingers. ‘Let’s have a go at that bow tie.’

But despite the fact that we undo the clip-on bow tie and lay the pieces out all over the large double bed in the Wilkinsons’ bedroom we do not make any progress. They obviously make clip-on bow ties in a different way.

‘Now we’re got a problem,’ says Mr Wilkinson. ‘We’ve destroyed the clip-on bow tie and we can’t tie the velvet bow tie. What am I going to do?’

‘I feel awful about this, Mr Wilkinson,’ I say. ‘The whole thing was my idea and I’ve let you down. Let me have a go at tying the velvet bow tie. It can’t be too difficult.’

But it is difficult. Especially when I am facing Mr Wilkinson. There is something about the smell of his after-shave lotion being right under my nose and the half smile on his lips as he looks into my eyes. ‘I think it would be easier if I got behind you,’ I say. ‘Then I would feel as if I was doing it, if you know what I mean.’

‘Righty-ho!’ says Mr Wilkinson. ‘I’ll try anything once. Where do you want me?’

‘Sit at the dressing table,’ I say. Rex Wilkinson does as I suggest and I kneel down behind him and slide my arms round his neck.

‘Ooh, that’s nice,’ he says, wriggling his shoulders.

‘Please, Mr Wilkinson,’ I say. ‘I’m trying to concentrate. I can’t remember whether it goes over or under.’

‘Let’s try both,’ says my client, rubbing his hands together.

‘Dad. What you doing?’ The voice is shrill and accusing and belongs to Courtenay Wilkinson who is watching us from the door.

‘Er-hem. Rose is helping me tie my bow tie,’ says Mr Wilkinson, sounding uncomfortable. He removes my arms from around his neck and stands up. ‘Go back to bed!’

‘Daddy can’t do it,’ I say with a bright friendly smile. Courtenay looks at me with distrust and loathing in his eyes and then turns his gaze on his father.

‘Are you going to teach her to do press-ups like Aunty Brenda?’ he asks.

Mr Wilkinson turns scarlet. ‘Back to your room!’ he shouts. ‘I don’t want another word out of you. Rose will be along to tuck you up in a minute.’

‘Don’t want Rose. Want Mummy.’ Courtenay’s lip is trembling.

‘You heard what I said!’ Mr Wilkinson strides across the room to confront Courtenay and receives an expertly delivered kick in the shins – Courtenay Wilkinson must be one of the only children in the country with steel toe-caps in his slippers. There is a brief struggle and Courtenay is overpowered and carried from the room. A door slams and the sound of his screams and curses becomes more muffled. Mr Wilkinson returns looking even more harassed.

‘I knew those bloody karate lessons were a mistake – excuse my French,’ he says. ‘Teaching those two unarmed combat was like issuing the Manchester United fans with flame throwers.’ He realises that he may be creating the wrong impression and pounds his hands together briskly. ‘Not that there’s anything basically wrong with the boys, of course. Just normal high-spirited lads.’ He has to raise his voice so that I can hear the last bit over the rising tide of Courtenay’s screams. Benedict appears to be howling as well. Mr Wilkinson looks at his watch. ‘Good heavens! Is that the time? I’m going to miss the curtain if I don’t hurry.’

‘What about your tie?’ I say. ‘Do you want me to have another – – ’

‘No.’ Mr Wilkinson shoots a worried glance towards the boys’ room. ‘I don’t think so. They get funny ideas in their heads sometimes. I’ll do it on the way. Help yourself to a drink if you want one. The telly is straightforward and everything is where you’d expect to find it in the kitchen.’ He squeezes my hand and lowers his voice confidentially. ‘You’re a very attractive girl, do you know that? I hope we have you again.’

‘Thank you,’ I say. ‘What time will you be back?’

Mr Wilkinson looks thoughtful. ‘Well, let’s see. There’s usually a celebration in the dressing room after the first night. It could be a bit late – say, after midnight. That won’t be too late for you, will it? I expect you’ve stayed up that late before?’ He gives me another Wilkinson wink and I assure him that any time will be all right with me. ‘Don’t worry about the boys,’ he shouts. ‘They’ll settle down in a few minutes.’ He has to shout because that is the only way I am going to hear him. Honestly, I would hate to live next to the Wilkinsons.

I wait hopefully for five minutes after Mr Wilkinson has left the house but the noise level is still unbearable. I will have to do something. ‘Now, now,’ I say, nervously sticking my head round the bedroom door. ‘What’s all this noise about, then? This isn’t going to help us grow up big and strong, is it? You know what they say about sleep before ten?’

Benedict’s tear-filled eyes glow red over the sheets. They look as if they have got a lot of tears left in them. ‘No,’ he says.

‘Oh.’ I try and remember what they do say about sleep before ten. ‘They say it’s very good for you,’ I proffer, lamely.

Courtenay makes a rude noise which just may be natural. ‘I want a drink,’ he says.

‘Water?’ I say.

‘Coca-Cola.’

‘You can’t have a Coca-Cola now,’ I say. ‘It’s very bad for your teeth just before you go to sleep. And all those bubbles will give you the colly-wobbles.’

‘What’s colly-wobbles?’ says Courtenay.

‘Diarrhoea,’ says Benedict. ‘You’ve got that.’

‘No, I haven’t!’

‘Yes, you have!’

‘No, I haven’t!!’

‘How about a nice story?’ I say. ‘Do you know the one about Little Red Riding Hood?’

‘She gets rubbed out by the CIA,’ says Benedict smugly.

‘Not in my version,’ I say. ‘There’s this nasty old wolf – – ’

‘He’s not a wolf, he’s an FBI man,’ says Courtenay contemptuously. ‘He figures that Riding Hood is a subversive misappropriating funds earmarked for underdeveloped countries so he liquidates her.’

‘Where did you get all that from?’ I ask him.

‘From the book that Daddy reads us.’ Benedict hands me a thick volume entitled Nursery Stories with a Modern Message.

‘All right,’ I say, thumbing through it. ‘What about How Cinderella hit the Big Time?’

In the end we settle for Ali Baba and the Forty Investment Analysts and by the time that Ali Baba has been boiled in North Sea oil and the investment analysts have drawn up a tentative, outline, provisional, non-binding contract with a pilchard packaging plant, the children’s heads are beginning to droop. I pause in the narrative, wait a few moments until I hear the sound of regular breathing and then tiptoe out. Phew! Thank goodness for that. Those stories were so gruesome I was beginning to frighten myself. I am quite glad that I have got the remains of the strong gin that Mr Wilkinson gave me, to buck me up. I have just glugged it down and am reaching for the Radio Times when the telephone rings. It takes me some time to find it because it lives under the flared skirt of a knitted woollen doll and I am slightly flustered as I raise the receiver to my ear. ‘Hello,’ I say. ‘Er – Chingford four three two one.’

‘Rosie, is that you?’

The breathless catch to the voice is immediately known to me.

‘Geoffrey!’ I gasp. ‘How did you know I was here?’

‘I rang up your mother,’ says Geoffrey. ‘Or rather – I rang up you and your mother answered the phone. Home on leave, are you?’

‘Er – no,’ I say. ‘I’ve finished with the army.’

‘I am glad,’ says my old beau. ‘I never thought the WRACs was really you.’

‘No,’ I say. ‘Well, Geoffrey, it’s nice to hear your voice. To what do I owe the pleasure of this call?’ I cannot help feeling a slight tremor of excitement as I await the answer to my question. My bitter-sweet romance with Geoffrey has waxed and waned over the years and I have never been able to truly analyse my feelings for the man. When he is attentive, I don’t want him. When he is not about, I do. I suppose all women are a bit like that.

‘I’d love to see you,’ says Geoffrey eagerly.

‘Not tonight, surely,’ I say. ‘You know I’m babysitting.’

‘I could pop round for a bit – I mean, for a little while,’ says Geoffrey. ‘Nobody would mind. There’s no need why they should know.’

‘Well – – ’ I pause, waiting to be persuaded. Geoffrey does not say anything. Oh dear, I do wish he would display a little more gumption sometimes. Not enough to do anything untoward, of course, but just enough to be told not to. Sometimes I wonder if anything really did take place behind the heavy roller at the Eastwood Tennis Club after somebody put something in the punch.

‘If you don’t think it’s a good idea I quite understand.’

‘It’s terribly impulsive of you, Geoffrey,’ I say trying not to sound sarcastic. ‘Just for a little while then. You know the address, do you? Fifty-seven, Glastonbury Gardens.’

‘Got it,’ sings out Geoffrey. ‘Super! I’ll be round as soon as I’ve finished marking my balls.’

I put the telephone down and stare thoughtfully into the artificial flame effect of the plastic-bronze cowled simulated teak surround Magi-Glo Gas Fire. One of the buttons on the lilac plastic padding has dropped off but it still throws out a cheerful, heart-lifting glow. It will be interesting to receive Geoffrey in the Wilkinsons’ home. I will be able to imagine that it is our own and gauge a reaction to my long-time boyfriend in a setting which is not dominated by my own or his parents. I immediately start puffing up the cushions and arranging the magazines in a tidy pile. There is no sound from Benedict and Courtenay and when I peep my head round the door they are both lying on their backs with their mouths open and snoring – yes, snoring. I never knew that children snored. Still, I never knew that there were children like Benedict and Courtenay Wilkinson – and that is saying something when you have a sister like Natalie.

I feel quite light-hearted after the gin and take another look in the Wilkinsons’ bedroom. It is fun nosing round other people’s houses, isn’t it? Mrs Wilkinson has a very sexy negligée-type robe and for a moment I flirt with the idea of putting it on to receive Geoffrey. I wonder what he would say – and do? Still, you can’t really behave like that, can you? I wander over to the dressing table and examine the bottles. Mrs Wilkinson certainly has enough perfume. What is this one? ‘Forbidden Love’. Umm. Sounds pretty potent. I remove the stopper and take a sniff. Wow! I wonder what Geoffrey would make of this? No harm in finding out. A little dab won’t be noticed. It will have worn off by the time the Wilkinsons get back. I pop some on my wrists and between my breasts and behind my ears – Geoffrey does not smell very well – I mean, he does not have a very powerful sense of smell – and put the bottle back. I have undone the top two buttons of my blouse in order to apply the perfume and I decide to leave it like that. There can be no harm in subjecting Geoffrey to a little feminine allure. It will be interesting to see if he notices.

I go downstairs and see that Mr Wilkinson has left his gin on the mantelpiece next to the clock set in the side of a carved elephant – I suppose you never forget the time. Ho! Ho! It seems a pity to waste it – the gin, I mean. I take some more ice from the plastic pumpkin and turn on another bar of the gas fire. Live dangerously, Dixon, this could be one of the most important nights of your life. A new career under way and – who knows? – perhaps a proposal of marriage to consider. I may be reading between the lines but I thought that Geoffrey seemed a little pent up and breathless on the phone tonight. As if he had been turning something over in his mind for a long time and come to a decision. What shall I say if he asks me? Now that Captain Rollo D’Arcy of the Royal Horse Guards seems to have gone out of my life for ever, I am not exactly overburdened with suitors. Mum did say wistfully that she wondered when I would be needing a babysitter of my own. Not that I am worried, of course. I have no intention of rushing into marriage with Geoffrey Wilkes unless I am certain that is what I want. Oh dear. It is difficult. If only Geoffrey was a little more exciting and some of the exciting men were a lot more dependable.