Полная версия

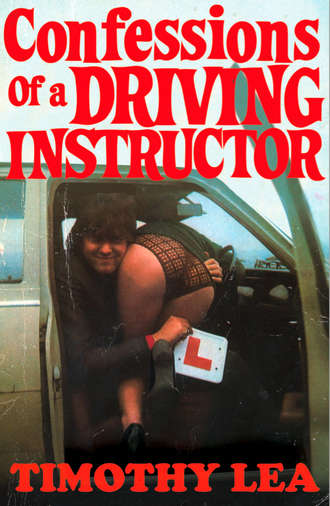

Confessions of a Driving Instructor

Driving lessons can be a lot of fun – if you’re the instructor and you get pupils like Timmy found when he changed jobs.

Mrs. Bendon liked to make her boarders really comfortable. Dawn was more interested in the back seat than the lessons.

Mrs. Dent had her own unusual treatment for injuries. Mrs. Carstairs liked to paint – and got very closely involved with her subjects.

All things considered, Timmy found that being a driving instructor was even more enlightening than cleaning windows.

CONFESSIONS OF A DRIVING INSTRUCTOR continues the autobiographical saga of the erstwhile Timothy Lea begun in CONFESSIONS OF A WINDOW CLEANER.

Publisher’s Note

The Confessions series of novels were written in the 1970s and some of the content may not be as politically correct as we might expect of material written today. We have, however, published these ebook editions without any changes to preserve the integrity of the original books. These are word for word how they first appeared.

CONFESSIONS OF A DRIVING INSTRUCTOR

by Timothy Lea

Contents

Publisher’s Note

Title Page

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

About the Author

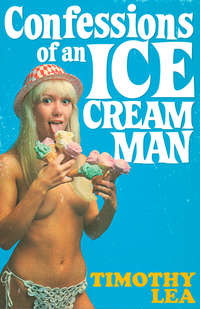

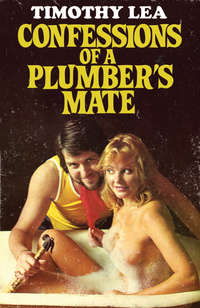

Also by Timothy Lea

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

I don’t know how you would react to finding your brother-in-law knocking off your fiancée in the potting shed, but I can tell you that I was annoyed. Not annoyed so much as bloody choked. I mean, what a liberty. My own brother-in-law! The horny bastard who was living in the room below mine at the ancestral home of the Leas in Scraggs Road. It would have broken my sister’s heart. Poor Rosie thought the sun went in every time he pulled up his trousers. But what about me? Why was I being so generous with my sympathy? The cunning of the bitch. All that ‘butter wouldn’t melt between my legs’ innocence. The reproving looks every time I used a four-letter word, her little hand sneaking over the top of her glass after the second Babycham. Well, she certainly had me fooled.

That’s what annoyed me most of all, really. I’d been fooled. It wouldn’t have been so bad if I’d reckoned her as being a bit on the flighty side, but I’d never had an inkling. She’d really made a mug out of me.

I must confess that when I’d stalked off into the night, leaving them clambering out of the wreckage of the shed, I though seriously about going straight home and sobbing the whole story to Rosie. But as I strode through the drizzle and my blood cooled a bit, two things stopped me. One was the praiseworthy desire to spare my sister’s feelings already alluded to, and the other, and much stronger emotion, the fear that everybody in the neighbourhood would soon know that I had been shat on by sexy Sidney, Balham’s answer to the piston engine. If I dropped Sidney in it, he wouldn’t be slow to make sure that everybody in S.W.12 knew that my fiancée preferred him in bed, in a shed, or anywhere, and I couldn’t have stood that. Some of the things I’d heard her whispering to him in the shed fair made my blood curdle; mainly because I had a horrible suspicion that she had never felt like that with me. I didn’t want to think about it, but I couldn’t help it.

Mum and Dad had gone to bed when I got home and I tiptoed up to my attic room and lay there staring at the roof (I didn’t have much alternative because it was about three inches above my head) and wondering what I should do. As is my normal habit in situations like that, I eventually decided: nothing. Apart from Rosie and my reputation, there was the job (Sid and I were partners in a window-cleaning business) and though we went pretty much our own ways, I didn’t want to rock the boat too much there.

The more I rationalised it all the more I put the blame squarely on Liz’s shoulders. I hated her, but at the same time I wanted her more than I’d ever done in the past. Not with any shred of affection, but with a desire to batter her to death with my body so that she died gasping “You are the greatest” with a look of unspeakable contentment etched across her glazed eyeballs. It had been this ability to look on the brighter side that has been my salvation in many chastening situations.

Not that I was prepared to give Sid a book token or anything. The bastard would be dead scared that I’d spill the beans to Rosie and I decided to let him sweat on it. I didn’t hear him come in before I fell asleep and the next morning when I got down to breakfast early, there was no sign of him or Rosie. Dad was sitting there studying his form book and Mum was frying bread. Dad is very working-class because, though he never does anything, he’s always very punctual about not doing it. He gets down to the Lost Property Office where he works a quarter of an hour before they open and then spends forty minutes in the cafe opposite before he strolls in and bleats like buggery about some kid who comes in five minutes late and gets down to work immediately.

“Morning,” I say cheerfully.

“Morning,” says Mum.

Dad grunts without looking up.

“Have you seen your Dad’s Dentucreme?” says Mum. I shudder because I can’t stand false teeth at the best of times.

“I think Sid tried to clean his wet-look shoes with it,” I say.

“Oh, no! You must be having me on.”

“Straight up, Ma. Sid got mad because it took all the shine off and threw it out of the window.”

“Bloody marvellous,” says Dad. “Who does he think he is?”

“You’ll be able to ask him yourself,” I say, as Sid comes in trying to look all relaxed. I am glad to see that there is a lump under one of his eyes and his upper lip is grotesquely swollen. Mum notices immediately.

“Ooh, Sid, you haven’t been in any trouble, have you?”

“No, Mum. Somebody let a swing door go at me. It was an accident.”

He stresses the last word and there is almost a hint of pleading in his eyes as he looks at me.

“Looks as if Rosie has been having a go at him, if you ask me, Mum,” I say. “What have you been up to, Sid?”

“You and Rosie haven’t had words, have you?” says Mum, all worried-like. Mum can’t stand what she calls ‘an atmosphere’ and can remember when Sid came home rotten-drunk and tried to have Rosie on the stairs. This manoeuvre, difficult enough at the best of times and downright impossible when drunk and with Rosie trying to knee you in the groin, resulted in Sid slipping down fifteen steps and nearly doing himself irreparable damage on a loose stair rod.

“No, no,” says Sid. “Rosie and me are fine. It was an accident, I tell you.”

“Of course, I don’t suppose Rosie has seen your face yet, has she?” I say pleasantly. “You came in pretty late last night, didn’t you?”

“I don’t have to clock in, do I?” says Sid, and I can tell he is beginning to lose his temper.

“Come, come, dear,” says Mum, “I don’t think Timmy meant it like that. It’ll be a bit of a shock for Rosie, won’t it?”

“Too true, Ma,” I chip in. “It’s the kind of thing Rosie could get very distressed about.”

“You hadn’t been drinking, had you, dear?” says Mum. “I know it’s none of my business, but I think you ought to look after yourself a bit more. You’ve been looking quite peaky lately. You must get enough sleep if you’re going to be up and down those ladders all day. You only need one slip and that’s your livelihood gone. And with Rosie and, now, little Jason, you’ve got more than just yourself to think about.”

“Humf,” says Dad from behind his paper.

Dad is a first-rate judge of a layabout and has few contenders himself in the over-fifty category. He has always reckoned Sid to be a creep of the first water and not been slow to say so.

“He’s never thought about anyone else in his whole life and he’s not going to start now. You’re wasting your time there, Mother. Any man with a grain of self-respect wouldn’t still be living off his in-laws on the money he’s making. I know what his little game is. He reckons if he hangs on long enough, you and I will snuff it and he’ll have the house. Well, he’ll have to wait a damn long time, I can tell you. I’ll still be sitting here when he’s queueing up for his old age pension.”

“Oh, God! Not again! I can’t stand it at this time of the morning. How many times do I have to tell you? I don’t want your rubbishy old house.”

“‘Rubbishy’. Did you hear that, Mother? The sponging layabout has the gall to call our home ‘rubbishy’. If it’s not good enough for you, why do you stay here then?”

“I’m not staying here a minute longer than it takes me to save up the deposit on a flat. You know that as well as I do. And don’t talk about sponging. You get your rent every week. A bloody sight more than you deserve for this dump. I’m amazed the kid wasn’t born with web feet.”

“Oh, that’s nice, isn’t it? Did you hear that, Mother? Now he’s sneering at us. You’d like oil-fired central heating, I suppose, and a heated lavatory seat.”

“It’s quite warm enough, the length of time you spend sitting on it,” says Sid, and Dad goes on spluttering while Mum clucks away and the fried bread gets burnt. It’s all going very nicely, though it’s getting a bit far away from Rosie.

Luckily the little lady herself makes a timely appearance and immediately drops her lips to give the loathsome Sid his first kiss of the day. In such a position his battered phizog is clearly revealed to her.

“Oh, Sid,” she squeals. “How did you do that?”

“Yes, Sid,” I say, my voice heavy with menace, “how did you do that?”

“I’ve told you once, you berk. Somebody swung a door in my face.” He sounds worried.

“On purpose?” howls Rosie. “How could anybody do a thing like that?”

“Maybe Sid rubbed them up the wrong way,” I say, helpfully. “You’d be surprised some of the things he gets up to.”

I divide my gaze between Sid and Rosie and they stare at me blankly, but for different reasons.

“You aren’t in any trouble, are you, Sid?”

Very good question. Sid swallows hard and is about to open his mouth when Mum decides it’s time to change the subject.

“I thought your Elizabeth was looking very nice the other night,” she says to me. Stupid old bag. Trust her to let Sid off the hook. But maybe I can turn it to advantage.

“I wouldn’t know about that,” I say, grudgingly.

“What do you mean, ‘you wouldn’t know’?” says Rosie, turning her attention away from Sid. “She’s a lovely girl. You should be very glad to have her.”

“Yes,” says Sid, chirping up a bit, “very glad.”

“Depends what you mean by ‘have’,” I say, giving Sid the evil eye.

“I don’t understand you.” Rosie shakes her head.

“Well, Rosie, I suppose I’d better tell you—and you, Mum. You’ve got to know sooner or later—” My voice is trembling and even Dad puts down his pencil and stares at me. Sid’s face screws up like a man threatened with a red hot poker and his mean features plead for mercy.

“I don’t really know how to say this …” Sid pulls back from the throng and his hand dives into his back pocket.

“… but last night I saw Liz and …” Sid pulls open his wallet and points feverishly at a thick wad of notes. My power is total and I can’t resist another turn of the knife.

“It was in her Dad’s potting shed …”

“Her Dad’s potting shed?” says Mum. “I hope you weren’t up to no good.”

“Oh, no, Mum. Not me …”

Sid staggers back against the sink to await the mardi gras, as the frogs call it.

“We had a talk and, well, we decided it wasn’t on.”

“Oh, no, dear. I am sorry to hear that. Are you sure it isn’t just a tiff?” says Mum.

“No, Mum. There’s a number of fundamental issues we disagree on.” (I got that from all those trade union interviews on the telly.)

“Like sex before marriage, I suppose,” sneers Dad, rubbing his fried bread into his egg yolk like he’s trying to clean the pattern off the plate.

“No, we both felt the same about that,” I say, meaningfully, giving Sid’s wallet a hard glance. Sid’s smile is what you might call conciliatory.

“Oh, I am sorry,” says Rosie. “I liked Liz; didn’t you, Sid?”

Sid gulps and nods his head.

“From what little I saw of her.”

Cheeky bastard! That’s going to cost him a few extra quid.

“What do you mean, ‘little’? You two were getting on like a house on fire that night up at the boozer.”

Blimey, I think to myself, even my dozey sister could see what was going on. What a prize berk I must be.

“The course of true love never runs smooth,” chips in Mum. “Don’t be too disappointed. I’m certain it’s not over yet.”

“Oh, I am, Mum. From my point of view, there’s no going back on what happened last night.”

“But how can you suddenly be so certain!” bleats Rosie. “I mean, you’ve been going steady with Liz for months now. You’re not going to tell me that one little row can be the end of everything.”

“It wasn’t so little,” I say with a quiet intensity that would have made Godfrey Winn sound like a fairground barker. “There are some things so fundamental in a relationship that when you stumble across them they spell make or break.”

“I don’t understand what the hell he’s talking about,” says Dad. “You mean you found she was in the family way?”

The stupid old sod doesn’t know how close he is but I dismiss him with a humoring nod of the head and address myself to Sid and his disappearing wallet.

“No, Dad, it’s nothing your generation would understand. I think Sid knows what I mean, don’t you, Sid?”

Sid blushes before my penetrating gaze and nods vigorously.

“Yes, Timmy,” he says, “I had the same problem myself once.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” says Rosie. “It certainly wasn’t with me. We never had a wrong word the whole time we were engaged.”

“I don’t ever remember that you were engaged,” says Dad.

“Now, Dad …” says Mum.

“If he’s going to start getting at me …” says Rosie.

“I’d better be getting going,” says Sid. “I’ve got an early job. I’ll have some breakfast at the caff.”

I catch up with him in the hall. “Oh, Sid,” I say, “I got the impression in there you might be able to stand me a few bob.”

“How much? A fiver?”

“You must be joking. That’s what you’d pay up the West End. For family it comes a bit more expensive. Twenty-five nicker.”

“Nice bleeder, aren’t you? You’d make a good ponce.”

“Thanks. It takes one to know one. Just take it as being damages for breach of promise.”

“I never promised anything.”

“O.K. Well, consider yourself an unofficial co-respondent.”

“It’s more like bloody blackmail.”

“It is bloody blackmail and you’re bloody lucky to get off with twenty-five nicker and a bunch of fives up the bracket.”

“O.K. Well, I suppose it was worth it.”

“Don’t push it.”

And so on those pleasant terms we part with Sid lighter by the weight of five crisp fivers which he counts three times in case an extra one might have got stuck to them.

It is shortly after this event that, much to my father’s surprise and mother’s sorrow, Sid makes good his promise and moves Rosie and Jason into the wonderful new world of a Span flat, overlooking the common. Dad congratulates himself that it is his non-stop rabbiting that has done the trick but I have a shrewd suspicion that it is the threat of me blurting out a few home truths to Rosie—plus the not inconsequential demands I am making upon his surplus funds. Some might feel the odd pang of guilt, but I console myself with the thought that I am feathering my beloved sister’s nest as well as my own.

With the departure of the Boggetts (that was Sid’s name, poor sod) I move my photographs of the Chelsea football team (F.A. and European Cup winners: ‘We are the champions’) down to their bedroom and prepare to lord it a bit. But things don’t work out the way I’ve hoped. Mum is distraught about losing ‘her little Jason’ and keeps going on about all his lovable little habits like pissing in the coal bucket, and Dad misses having Sid to whine at and starts taking it out on me. Between the two of them, they are beginning to make me feel quite nostalgic for the old days. What I would have done next I’ll never know because at that moment fate intervenes and the whole course of my life is changed at one stroke. Sounds fascinating, doesn’t it? Oh, well, please yourself.

I have already mentioned that I shared a window cleaning business with Sid and readers of the previous volume of my memoirs (Confessions of a Window Cleaner—Sphere 1971. Ed.) will recall that this led to the odd entanglement with what my old schoolmaster used to call members of the opposite sex. It was such an occasion that led to my eventual, and literal, downfall.

I remember the day well because it was late summer and very hot in a way that only happens in the week after everyone has come back from their August bank holiday. Dogs panted in shadowy doorways and the heat seemed to muffle the noises of the street so that I might have been working in a dream as I lazily swept my squeegee over the top floor windows. I was operating in the front garden of a row of comfortable middle-class semi-detacheds behind Nightingale Lane and was stripped to the waist, not because I wanted to give any bird the come-on, but because I wanted to improve my suntan—though the two things are not entirely unconnected. Most of the windows round here are thicker with net curtains than Dracula’s wedding veil, but Mrs. Dunbar must have had hers in the wash because I can see straight through into her kiddies’ nursery.

Mrs. D. is on her hands and knees behind a rocking horse, and I note with satisfaction the pattern of her knickers showing through her skirt as her delicious little arse bulges over her haunches. Mrs. D. is a regular client of mine but I’ve never had an inkling that there might be anything there for me. To be honest, I find her a bit upper-class and self-confident. I prefer a bird who is more dithery and unsure of herself. Nevertheless, in my sun-sated mood and with a couple of pints from the wood inside me, there are a lot worse things to look at. She has the horse’s tail in her hand and turns towards me and shrugs her shoulder. This is a gesture she could repeat to advantage because she isn’t wearing a bra and her breasts give a little jump like startled kittens. I can see the kittens’ noses, too, pressing temptingly out towards me. Cruel Mrs. D. No animal lover should be so frustrated. The no-bra look has been slow to penetrate into the Clapham and Wandsworth Common area and is another indication of upper-class sophistication and decadence which leaves me trembling with a mixture of desire and impotence—two bedfellows that seldom give each other much pleasure.

Mrs. D.’s gesture is meant to indicate that she doesn’t know what to do with the rocking horse’s tail and a number of tempting alternatives flash across my mind. I reject them and take the opportunity to close the distance between us.

“Let me give you a hand,” I say gallantly, and I’m over the sill before she can say ‘Piss off.’

“Oh, that’s kind of you,” she says breezily. “I’m afraid he’s seen better days.” She isn’t joking because most of the leather-work is hanging off and the screws that hold the horse to its frame all need tightening up. I make a few tut-tutting noises and send her off for the tools to do the job. The way her eyes flit lightly across my pectorals does not escape me. When she comes back I’m tapping in tacks and she asks me if I’ve got any children.

“Don’t think so. What makes you ask?”

“You seem to know how to mend toys.”

“My sister and her husband used to live with us. The kid smashed everything it could get its hands on. I got plenty of practice. You know what kids are like. They enjoy taking things to pieces but they don’t want to put them together again.”

She nods.

“So you’re not married?”

“No. I was thinking about it, but things didn’t work out. You must be, though. How many kids have you got.”

“Two. They’re with their father at the moment. We’re separated.”

“Oh, I am sorry.” In fact, I’m chuffed to NAAFI breaks because there is nothing more likely to put the mockers on a beautiful romance than the threat of a couple of kids bundling in on you at any moment.

“Don’t be. I’m not.” She rubs her hands together lightly and pats her hair. “You’re a fabulous colour.”

“It’s easy on this job.”

“I envy you when it’s like this.”

“Well, you haven’t got far to go yourself.”

“I have to think of the neighbours. Would you like a beer? I think there’s some in the ’fridge.”

Another sign of class. Mostly it’s a cup of tea with my customers. But whatever it is, any form of refreshment is a favourable omen. Many is the pot of cha I’ve known to go cold with only the two cups out of it.

“That’s very kind of you.”

A few moments later she’s back just as I’ve finished the rocking horse.

“Oh, that’s much better. I’d hardly recognise him. The children will be pleased. I hope this is all right. It’s lager.”

“Smashing! Cheers!”

“Cheers!”

I’m down on the floor so I lean back against my handiwork and rub the cool glass against my cheek. She is standing above me pulling at the horse’s bridle as if it is real. I can see up her skirt but not as far as I’d like to. I feel keyed up the way I do just before going out to play football. The sunlight is coming through the window in chunks so you can see thousands of particles of dust dancing in it.

“You said you were nearly married once, didn’t you?”

“Did I?”

“Yes. You implied it, anyway. What went wrong? Forgive me asking, but it’s a subject I’m particularly interested in at the moment.”

“I found the bird I fancied having it away with my brother-in-law.”

“The one that lives at home with your sister?”

“He used to. They’ve got a flat up by the common now.”

“You didn’t like that? I mean, him sleeping with your girlfriend?”

“Not very much. I mean, it doesn’t seem the best recommendation for your future wife, does it?”

“I don’t know. At least you know where you stand with her.”

“It’s who else is standing with her I’d be worried about.”

“You’re the jealous type?”

“You could put it like that.”

“Jealousy is a very self-destructive emotion.”

“Not with me, it isn’t. I’m the last person that gets destroyed.”

“Surely the concept of sexual faithfulness is a bit out of date, isn’t it? Are you seriously going to tell me you will remain faithful to your wife when you do get married? The opportunities you must have in a job like this.”

I try to look as if the thought had never occurred to me.

“I reckon it’s difficult for me.”

I know this remark is going to get her all worked up, but there is no point in putting off saying it. I’m all for complete sexual freedom for women in theory, but the moment some horny bastard gets near my bird a phial of sulphuric acid explodes in my stomach and little green bells start ringing as I look around for an axe. That’s the way I am and I can’t see myself changing.